Honduras

HONDURAS, a republic occupying the central portion of Central America, with a coastline of 400 m. on the Caribbean sea and a frontage of some 4o m. on the Gulf of Fonseca, on the Pacific Ocean. It is bounded on the north by the Caribbean sea, on the east by Nicaragua, on the south by Nicaragua, the Pacific ocean and Salvador, and on the west by Guatemala. (See CENTRAL. AMERICA MAP.) The name is Spanish (it may be translated "wave like") and is explained with equal insistence either as referring to the depths off shore, or to deep, wave-like valleys and hills which scar the entire country, excepting for the relatively narrow coastal plains on either shore. The country faces on the sea to the north and on inlets on the north-west, where the boundary is the Gulf of Honduras which forms the only Caribbean frontage of the neigh bouring country, Guatemala, as well as the southern boundary of Belize or British Honduras. Around many inlets and lagoor}s the coastline follows a generally easterly direction until it reaches Cape Gracias a Dios (Cape "Thanks-to-God"), named, it has been suggested, because there the coast turns sharply south and the Spanish mariners who were seeking a westward passage gratefully found themselves again skirting a north and south shore line that might possibly open into the passage to the long-sought Oriental islands. Cape Gracias a Dios marks the boundary of Honduras and Nicaragua, which continues inland along the river variously known as the Wanks, Segovia or Coco. The frontier, which is still in dis pute and runs through a sparsely inhabited territory which fur nishes a base for revolutionary movements between the two countries, crosses the continental divide and at present follows the river Negro to the Bay of Fonseca. There, for a short dis tance, Honduras fronts on this great arm of the Pacific, holding sovereignty over the islands of Tigre (where its Pacific port, Amapala, is situated), Sacate Grande and Gueguensi. The bound ary line with Salvador starts at the mouth of the river Goascoran and follows an irregular line through the mountains, first in a northerly and then in a westerly direction, to a point directly west of Ocotepeque : there the boundaries of Honduras, Salvador and Guatemala meet. The boundary line between Honduras and Guatemala has been in dispute for nearly four centuries, and has been a serious question since the independence and break-up of the captain-generalcy of Guatemala into the five countries of Central America. Along the western frontier the line is fairly well ac cepted, but as it approaches the Caribbean the divergence of claims covers a relatively great area, whose growing economic importance, owing to the increasing banana industry, became an important issue in 1928. Following the mediation of the secretary of State of the United States, the whole subject was in that year submitted to the decision of a Central American tribunal under the 1923 treaties.

Physical Features.

The general aspect of the country is mountainous ; its southern half is traversed by a continuation of the main Nicaraguan Cordillera. The chain does not, in this republic, approach within 5o or 6o m. of the Pacific ; nor does it throughout maintain its general character of an unbroken range, but sometimes turns back on itself, forming interior basins or valleys, within which are collected the headwaters of the streams that traverse the country in the direction of the Atlantic. Never theless, viewed from the Pacific, it presents the appearance of a great natural wall, with many volcanic peaks towering above it and with a lower range of mountains intervening between it and the sea. It would almost seem that at one time the Pacific broke at the foot of the great mountain barrier, and that the subordinate coast range was subsequently thrust up by volcanic forces. At one point the main range is interrupted by a great transverse valley or plain known as the plain of Comayagua, which has an extreme length of about 4o m., with a width of from 5 to.15 miles. From this plain the valley of the river Humuya extends north to the Atlantic, and that of the Goascoran south to the Pacific. These three depressions collectively constitute a great transverse valley reaching from sea to sea, which was pointed out soon after the conquest as an appropriate course for inter-oceanic com munication. The mountains of the northern half of Honduras are not volcanic in character and are inferior in altitude to those of the south, which sometimes exceed Io,000 feet. The relief of all the highlands of the Atlantic watershed is extremely varied ; its culminating points are probably in the mountain mass about the sources of the Choluteca, Sulaco and Roman, and in the Sierra de Pija, near the coast. Farther eastward the different ranges are less clearly marked and the surface of the country resembles a plateau intersected by numerous watercourses.The rivers of the Atlantic slope of Honduras are numerous and some of them large and navigable. The largest is the Ulua, with its tributary the Humuya. It rises in the plain of Comayagua and flows north to the Atlantic ; it drains a wide expanse of territory, comprehending nearly one-third of the entire State, and probably discharges a greater amount of water into the sea than any other river of Central America, the Segovia excepted. It may be navigated by light draught steamers for the greater part of its course. The Rio Roman or Aguan is a large stream falling into the Atlantic near Trujillo, with a total length of about 120 miles. Its largest tributary is the Rio Mangualil, celebrated for its gold washings, and may be ascended by light draught boats for 8o miles. Rio Tinto, Negro, or Poyer or Poyas, is a considerable stream, navigable by small vessels for about 6o miles. Some English settlements were made on its banks during the 18th century. The Patuca rises near the frontier of Nicaragua, and enters the Atlantic east of the Brus or Brewer lagoon. The Segovia or Wanks is one of the longest rivers in Central America, rising within 5o m. of the Bay of Fonseca, and flowing into the Carib bean sea at Cape Gracias a Dios. Three considerable rivers flow into the Pacific—the Goascoran, Nacaome and Choluteca, the last named having a length of about 150 miles. The Goascoran, which almost interlocks with the Humuya, in the plain of Comayagua, has a length of about 8o miles. The lake of Yojoa or Taulebe is the only large inland lake in Honduras, and is about 25 m. by 6 to 8 m. ; its surface is 2,050 ft. above the sea. It has two out lets on the south, the rivers Jaitique and Sacapa, which unite about 15 m. from the lake ; and it is drained on the north by the Rio Blanco, a narrow, deep stream falling into the Ulua.

Honduras resembles the neighbouring countries in the general character of its geological formations, fauna and flora. Here, as in other Central American States, there are but two seasons, the wet, from May to November, and the dry, from November to May. On the moist lowlands of the Atlantic coast the climate is oppressive, but delightful on the highlands of the interior. At Tegucigalpa, on the uplands, a year's observations showed the maximum temperature to be 90° F in May, and the minimum to be 50° F in December (see CENTRAL AMERICA for Fauna, Flora, Climate).

The People.

The population of Honduras, according to official reports of 193o, is 854,184, of whom 4 24,3 24 are males. The census of 1916 showed a total of 605,997, of whom 299,952 were males. The area of Honduras is about 46,25o sq. m.; the density of population 15 to the sq. mile. The census figures of Honduras show a steady growth in population of 1 to II% per year; but an exact enumeration is virtually impossible, owing to the scatter ing of population and the large proportion of Indians. While the Indians—many thousands of them still living in a primitive state— constitute the majority of the population of Honduras, the cities are populated with mixed-bloods and the ruling groups are largely of almost pure Spanish descent. The Hondurans have been leaders of most of the various efforts to form a Central Union (see CENTRAL AMERICA), and the keen political acumen of the leaders has often sought expression in the most idealistic movements and in a broad analysis of the situations surrounding the relations of the Central American countries to each other, to the United States and to the outside world. There are about 20,000 negroes in Honduras, the larger proportion being British subjects imported under contract for work in the banana plantations. The descend ants of the negro slaves brought to Honduras during the colonial days still survive, some mixed with the Indians and others retain ing their race purity while evincing sound Honduran citizenship and patriotism. The negro blood, as in the other Central American countries, is closely confined to the Caribbean littoral. The Indian tribes of Honduras are fairly well defined in characteristics and race, being generally peaceable small farmers, but about 100,000 are officially estimated to live in the mountains in an almost wild state. The Carib Indians of tradition are believed to be the progenitors of certain groups on the Caribbean coast, who are the mainstay of the mahogany and pine lumbering interests of the river regions.There is some immigration into Honduras from Salvador, the thickly settled farming sections of that country sending forth an excellent type of farmer-immigrant into the sparsely populated regions of the Honduran interior. The driving overland of herds of cattle for the markets of Salvador and Guatemala has opened routes along which this immigration moves, and while it is as yet not a great item and ebbs and flows with the needs of the crops, it indicates a tendency toward readjustment of the populations in Central America. There is virtually no immigration from Europe, although some small groups of European farmers have arrived from time to time. The importation of negroes from the British West Indies is, as noted, on a contract basis which pro vides for their return to their homes after certain periods.

The chief city of Honduras is the capital, Tegucigalpa (q.v.), in the highlands of the interior, with a population of 38,95o. Other important urban centres are Comayagua (6,412) ; Juticalpa (8,000) ; Santa Rosa de Copan (13,000) ; San Pedro Sula (8,000) ; Puerto Cortes (4,000) ; Tela (3,50o) ; Trujillo (2,000) ; Pespire (7,000) ; Yuscaran (5,000) ; Ceiba (I o,000) ; Puerto Castilla (4, 000) ; Amapala (3,000) ; Nacaome (8,000) ; Santa Rosa (10,000) ; La Esperanza (I I,000) . In general, the population of Honduras flocks less to large towns than is common elsewhere in Spanish America, tiny farms being found at close intervals along the highways, and the rural life being more generally scattered over the country than the sparse population figures would seem to promise.

Political Organization.

The present Honduran constitution was promulgated on Sept. 10, 1924, previous instruments or modifications having been dated Dec. 11, 1825, Jan. 1839, Feb. 1848, Sept. 1865, Dec. 1873, Nov. 188o, Oct. 1894, Sept. 1904 (later replaced by the older instrument of 1894). The first article of the present constitution declares Honduras to be "a state separated from the Republic of Central America. Consequently it recognizes as a primal necessity return to union with other sec tions of the dissolved republic." The Constitution gives citizen ship, on mere declaration of desire, to citizens of the other Central American republics. Every Honduran male citizen of 21 years, or of 18 years if he is married or able to read and write, is en titled to vote.

The legislative power in Honduras is vested in a single chamber, the Congress of deputies, whose members are elected for four years, half being renewed every two years ; there is one deputy for each Io,000 inhabitants. No relative of the president "within the fourth degree of consanguinity or second of affinity" may serve in the Congress, nor may he be appointed to any high administra tive office. Congress meets on Jan. i of each year and sits for 6o days. The executive power is vested in the president, a vice president being elected at the same time, both for four years, by popular and direct vote. They take office on Feb. 1, 1925, 1929, etc. In case of a failure to obtain an absolute majority the election goes to Congress, which must choose between the three highest candidates for both offices. The president's cabinet con sists of from three to six secretaries of State, in charge of the usual government departments, each cabinet officer sometimes having two or more departments under his charge. The president and vice-president may not succeed themselves nor may any close relative succeed them.

The judiciary consists of a supreme court of five magistrates elected for four years by popular vote ; the judges may be re elected. Inferior courts are established under special laws. Justices of the peace are elected by popular municipal vote. Honduras is divided into 17 departments and one territory, each having a governor appointed by the president. The municipal govern ments are elected by direct vote. Police power is locally ad ministered, the centralized form of the republic permitting the use of Federal troops if necessary.

Religion and Education.

Education is under the direction of a cabinet officer, the minister of public instruction, who has a staff of inspectors and officials. Local schools are under the municipalities but are supervised by the department governors, as the schools receive help from the Federal government. Ac cording to the latest available statistics (1925) there were 987 primary schools, with 28,050 pupils out of a school population of 78,857. The secondary schools, entered after the pupils pass through five grades, include the National Institute and School of Commerce at Tegucigalpa, and seven other schools, with a total enrolment of something over 500. There are special industrial and agricultural schools, the national agricultural school near Comayagua being one of the best in Central America. There are three normal schools, one of them at Tegucigalpa, for both men and women, and there are branches for the education of teachers in • some of the secondary schools. The Central university at Tegucigalpa and special schools give technical education in law, medicine, etc.The constitution grants freedom of worship, and there is no State-supported church. Roman Catholicism is the chief re ligion, however. The Indians in some of the interior villages continue tribal rites ; but even there the Roman Catholic churches are established and the support of the natives is general.

Finances.-The

Honduran peso is on a silver basis, its value approximating 2s., or 5o cents United States currency, the old silver peso being the basis of exchange. While the coins of a dozen countries circulate freely, the United States dollar is the most common unit of exchange; one bank, whose chief offices are on the Caribbean coast where the banana companies are active, guarantees to redeem its own paper money at "two-for-one" with American dollars, while the official currency of the Banco National fluctuates with the price of silver. The revenues of Honduras are derived from the customs, and from the liquor, powder and tobacco monopolies. The revenues for the fiscal year ending July 31, 1926 were £944,568 and the expenditures estimated at L1,135,417. The deficit is made up from time to time by internal bonds, and by advances from the large fruit and mining corn panies against their estimated import and export taxes. The internal debt as of April 30, 1926, was 7,553,425 pesos, which included the following items: war claims, to Aug. 1, 1926, pesos; annual interest at 3%, pesos; due to banks, 2,000,000 pesos; due to private companies, 1,140,000 pesos; obligations incurred in connection with the National railway, 3,138,000 pesos.The entire public debt of Honduras as of Dec. 31, 1926, totalled £2,456,000. There is a United States loan of $500,000, and the old British loan, once carried, with 6o years interest, at £29, is fully accounted for in the total at £452,000, according to the agreement entered into on Oct. 29, 1925. This drastic re duction of the old debt was reached after many negotiations and periods of despair of ever being able to reach a settlement. The debt, the principal of which was contracted in 1867, 1869 and 1870, chiefly for the building of the National railway, was the balance being unpaid interest. The Honduran loan was floated at varying prices in London, the sales averaging around 20% of the face value, but the money that reached Honduras and went into the railway was only a fraction of the receipts, and the entire transaction was the cause of a parliamentary in vestigation whose hearings were published. While the scandal was finally placed at the doors of the Honduran agents in London and certain British brokers, the debt has been held against Honduras for 6o years, although various offers on both sides have been made. The final settlement arranged in 1925 recognizes the debt and accepts the terms of the Corporation of Foreign Bondholders. The debt is being paid through a 3% customs surcharge paid to the fiscal agent of the corporation which furnishes stamps to be affixed to customs documents. The agreement provides for pay ments of £20,000 annually and for interest of 8.86% on the un paid balance after 1925. The total will be £1,200,000. The Banco de Honduras is the chief bank; it is native owned and operated, and is the official bank of issue. It has branches throughout the country and collects and expends Government funds on order from the treasury. The only private bank of importance is the Banco Atlantida at Ceiba owned by one of the leading banana shipping companies ; it issues paper currency and has branches in the chief business centres.

Defence.

The army, under the Washington treaties of Feb. 7, is limited to 2,500 officers and men, but under the Con stitution all able bodied men are liable to 19 years' military service (2 years' active) at the age of 21 ; this provision. long existent, has been practically inoperative. Honduras developed military aviation earlier than most other Latin American countries, and the military aviation school outside Tegucigalpa has a num ber of planes, repair shops and hangars.

Economics and Trade.

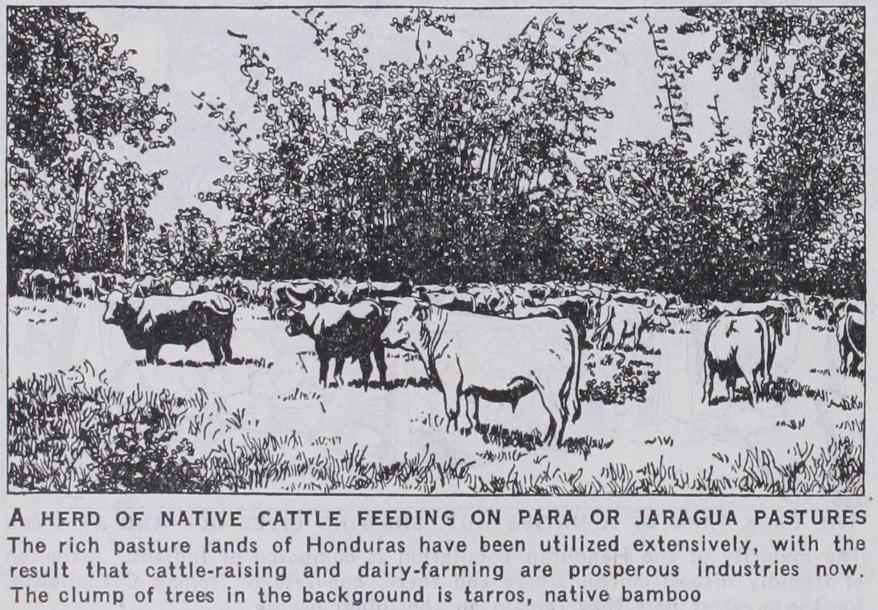

Honduras is a producer of tropical hardwoods, pitch-pine and dyewoods, of bananas and coffee, and of cattle in large numbers. Its mineral resources are considerable, but there are only two important mining companies, extracting gold and silver. Silver only reaches an important figure in ex ports, the total for the fiscal year ending July 31, 1927 being $1,362,718 (the conversion to American dollars is here followed, as the official data of the Pan American Union in Washington are in that currency) . The chief export item is, however, bananas, which totalled 17,090,182 bunches valued at $13,580,937, in 1926-27. Sugar, a growing industry, showed exports of 49,827,666 lb., valued at $1,363,179, together with $59,993 worth of molasses. Coffee exports were valued at hides at $82,548 and cattle (6,766 head) at $108,542. The United States took $13, of the $17,546,290 of exports in 1926-27, Great Britain $2,135,488, Canada $1,006,894, Germany $431,936, the Netherlands $64,949 and France $43,072. The total of exports shows a steady growth from $7,897,001 (1923-24) to $11,983,053 and to (1925-26) and to $17,546,290 (1926-27). Imports in 1926-27 totalled $10,630,416, of which the United States sent Great Britain $748,037, Germany $456,297, France $192,974 and Italy $113,180. Imports were $11,137,917 in 1923-24, $12,752,763 in 1924-25 and $9,899 in 1925-26. The largest single item of import was cotton cloth, $1,701,701; the second was oils, $564,133; the third flour, $362,580. Iron and steel manufactures, unclassified, totalled $646,007.

Communications.

The National railway originally built from Puerto Cortes to Potrerillos has 6o m. of track. The other rail ways total 45o m., including the following private lines : Trujillo railway, 74 m.; Vacarro Bros. line from Ceiba, 127 m. ; Cuyamel Fruit Co. line in Cuyamel district, 27 m. ; United Fruit Co. in Tela district, 125 m. ; Tropical Lumber Co., 7 m. ; Ulua branch, 32 miles. There is now a through highway between the Atlantic and the Pacific, including a boat trip across Lake Yojoa. The original highway in this system was the solidly and expensively built road up from San Lorenzo (the mainland terminus on the Pacific, 24 m. by water from the island port of Amapala in the Gulf of Fonseca), up to Tegucigalpa, a distance of 84 miles. This has been built for some years and is one of the most picturesque arterial highways of Latin America. The newer portion of the transcontinental highway leads from Tegucigalpa to Comayagua, 7o m., while from Comayagua to Lake Yojoa the road was built by the Honduras Petroleum company as a portion of its obliga tion for its oil concession. The lake is crossed by motor launch and the road continues from Limon, on the lake, to Potrerillos, the terminus of the railway. Other roads are gradually linking up interior towns, and while the dream of railway development still stirs the country from time to time, modern motor transport and good roads are now regarded as the surest and most permanent type of communications.There is aeroplane service along the Caribbean coast, and a line has been operated from time to time between Tegucigalpa and the Caribbean ports. There are landing fields at various points throughout the country. The steamship lines on the Pacific side serve Amapala, the only Pacific port, which, although land-locked and calm, has no deep water pier and offers no direct facilities for transport to the interior, as the highway to Tegucigalpa and the rest of the country is 24 m. distant and can be reached only by combined lighter-schooners, loaded again at Amapala after freight has been lightered from the steamers, or vice versa. On the Atlantic side, service is given by a number of banana fruit lines, which make quick trips to New Orleans, New York and Boston. Fruit ships now sail to British ports direct from Hon duras, and in general the banana traffic has given the north coast of Honduras exceptionally good steamship service—far better than a country of similar total trade would enjoy if its produce were less perishable. The telegraph and wireless systems of Honduras are well developed. The Tropical Radio, originally established by the United Fruit company for the convenience of its ships and agents, has transmitting and receiving towers at Tegucigalpa and various ports. The telegraph is Government operated and communicates with virtually every town in the re public and through the connections with other Governments' lines provides very cheap and relatively quick communication through out Central America.

Honduras, at the point now known as Cape Honduras, was the first landing place of Columbus on the soil of Central America, on his last voyage. Here the discoverer took possession of the continent in the name of the king of Spain, in 1502. The first settlement in Honduras was made by Cristobal de Olid under orders from Hernando Cortes, in Mexico, but the reports of the discovery of gold and silver mines tempted Olid to seek to set up a private principality, and Cortes made his memorable march from Mexico over the mountains and through the jungles and innumerable rivers of southern Mexico and Guatemala to re assume control. He founded Puerto Cortes in 1525, re-established order and the loyalty of the succeeding governors, and returned to Mexico in 1526. Honduras was incorporated into the captaincy general of Guatemala in 1539, and was then regarded as one of the promising sources of mineral wealth in the New World (see CENTRAL AMERICA). Honduras has been a continual sufferer from revolutions and war, one explanation being that, lying as it does between Guatemala, Salvador and Nicaragua, all fairly well balanced against one another, Honduras has been in a position to throw the balance to any of the contending nations, and has thus been subject to intrigue from all three sides. Each ruler of a neighbouring country, if he had designs on another, sought to put one of his puppets into power as president of Honduras, either by intrigue or by revolu tion, a practice hardly conducive to peace. Between 1867 and 187o, Honduras assumed its heavy burden of debt in the hope of obtaining the Interoceanic railway, but dishonesty at home and in London dissipated the moneys received from the loans, and left Honduras bankrupt and in trouble, both domestic and with her neighbours. Intervention by the neighbouring States placed Marco Aurelio Soto, a nominee of Guatemala, in the presidency in 1873, and he was re-elected in 1877 and 1880, following the promulgation of a new constitution. There was a succession of rulers and revolutions, from 1883 to 1903 in which year Manuel Bonilla was elected president and promised to consolidate and pacify the country. His enemies appealed to Jose Santos Zelaya, the dictator of Nicaragua and, in the course of the war which followed, American marines inter vened to end hostilities and Miguel R. Davila, a creature of Zelaya, became president of Honduras. In 1910 Davila was eliminated by a revolution led by Manuel Bonilla, and following the peace conference and the subsequent death of Bonilla in 1913, Dr. Francisco Bertrand became president. A liberal revolution led by General Rafael Lopez Gutierrez ousted Bertrand in 1919, and Gutierrez became president. Revolution threatened in 1922 and 1923, and in April 1924 the United States sent a personal representative of President Coolidge to mediate between the factions. Marines and bluejackets were landed twice and promptly withdrawn, and after various conferences and post ponements of the 1924 election, difficulties were smoothed out and Dr. Miguel Paz Baraona was elected president, with Pre sentacion Quesada as vice-president. They took office, under the new constitution which had been a part of the results of the dis cussions and conferences, on Feb. 1, 1925. In 1931 and 1932 seri ous uprisings occurred. But these were effectively crushed by the local government without foreign intervention. The age-old boundary dispute between Honduras and Guatemala came to a head in 1927 as the result of the development of banana lands in the controverted territory. The United States offered its good offices and when no results were obtained by conferences, the Secretary of State assumed the role of mediator and brought about a submission of the question to a tribune of arbitration, by which it was finally settled on Jan. 23, G. Munro, The Five Republics of Central America (1915) ; Wallace Thompson, Rainbow Countries of Central America (1926) ; L. E. Elliott, Central America (1924) ; and W. S. Robertson, History of the Latin American Nations (19a5). An early work of great interest and charm is E. G. Squier, Honduras; Descrip tive, Historical and Statistical (187o) . Official documents including messages of the president and statistical and demographical materials, have been published with considerable regularity by the Honduran Government. The Pan American Union, Washington, issues a booklet on the country and annual summaries of trade. Publications of the Department of Commerce of the United States, of the Council of the Corporation of Foreign Bondholders and of the Department of Over seas Trade in London contain valuable information. (W. TH0.)