Hongkong

HONGKONG, an important British island possession off the south coast of China in 22° 9'-22° 17' N. ; 114° 5'—II4° i8' E.

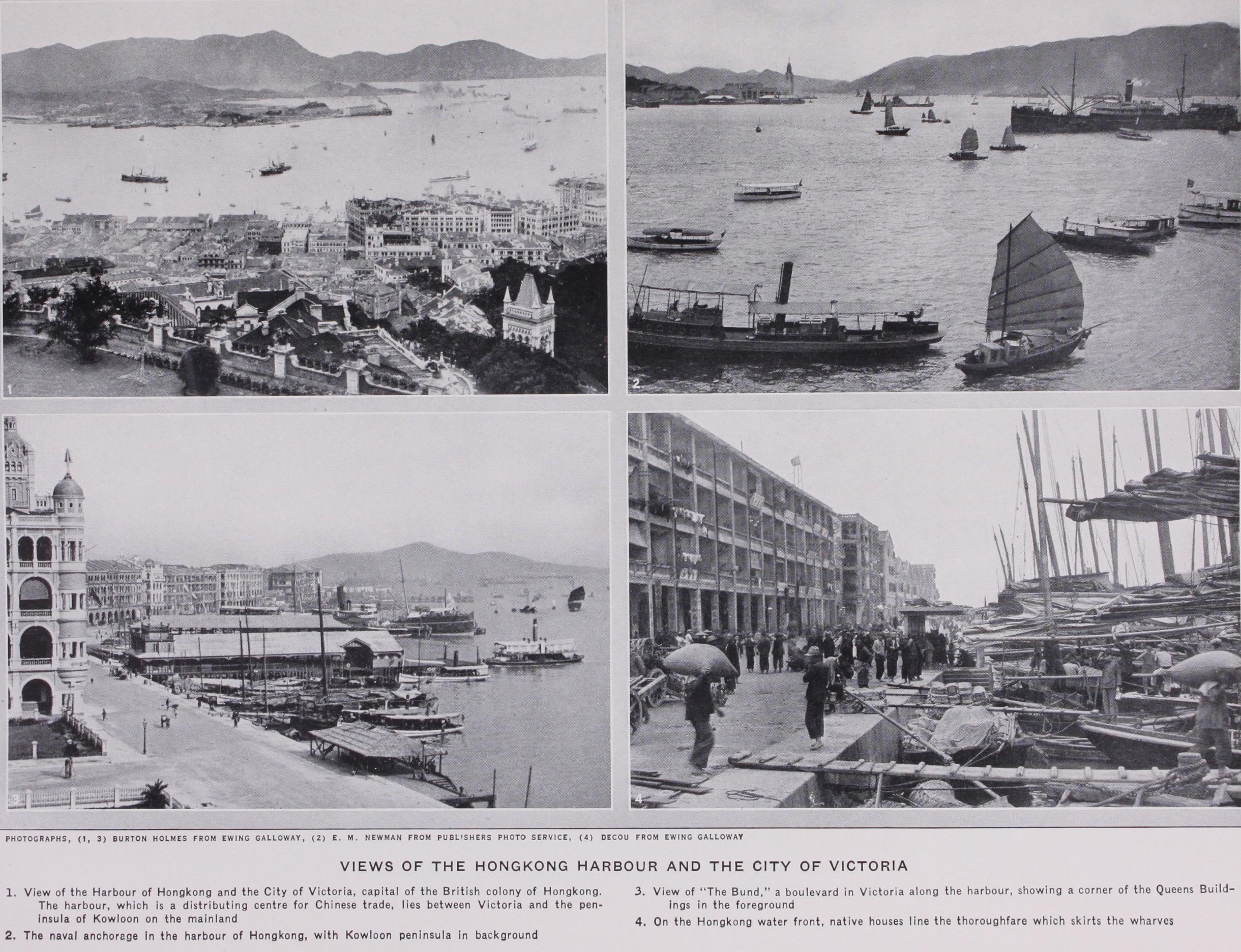

The present British colony of Greater Hongkong is a compact group of islands and peninsulas, comprising the island of Hongkong itself, the Kowloon peninsula and the so-called New Territories, which together command the entrance to the Canton river. The island of Hongkong lies 75 miles S.E. of Canton and has a dominant position in the group. It is very irregular in shape, about I I miles in length, and has an area of about 32 square miles. It is separated from the mainland by a channel about a mile broad between Victoria, the island capital, and Kowloon point, but narrowing at Ly-ee-mun Pass to about half a mile.

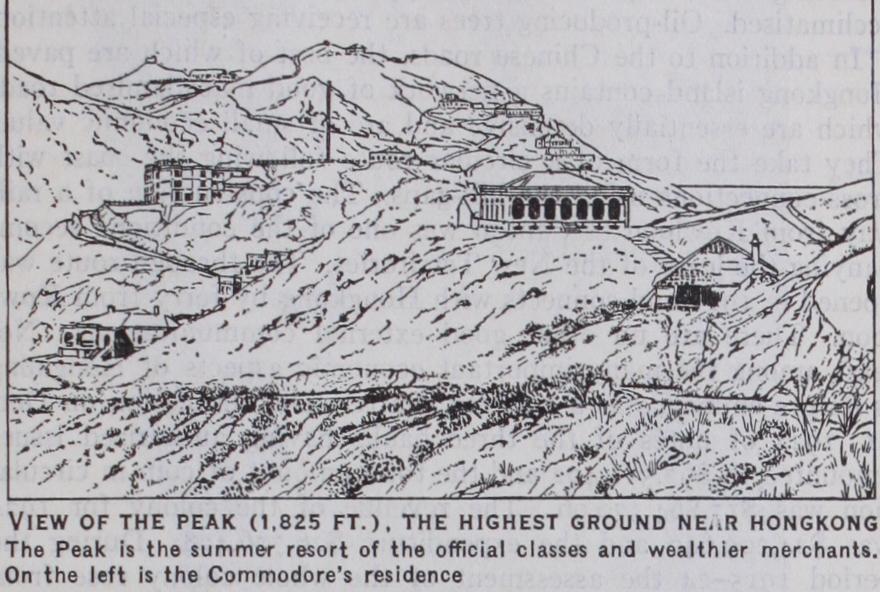

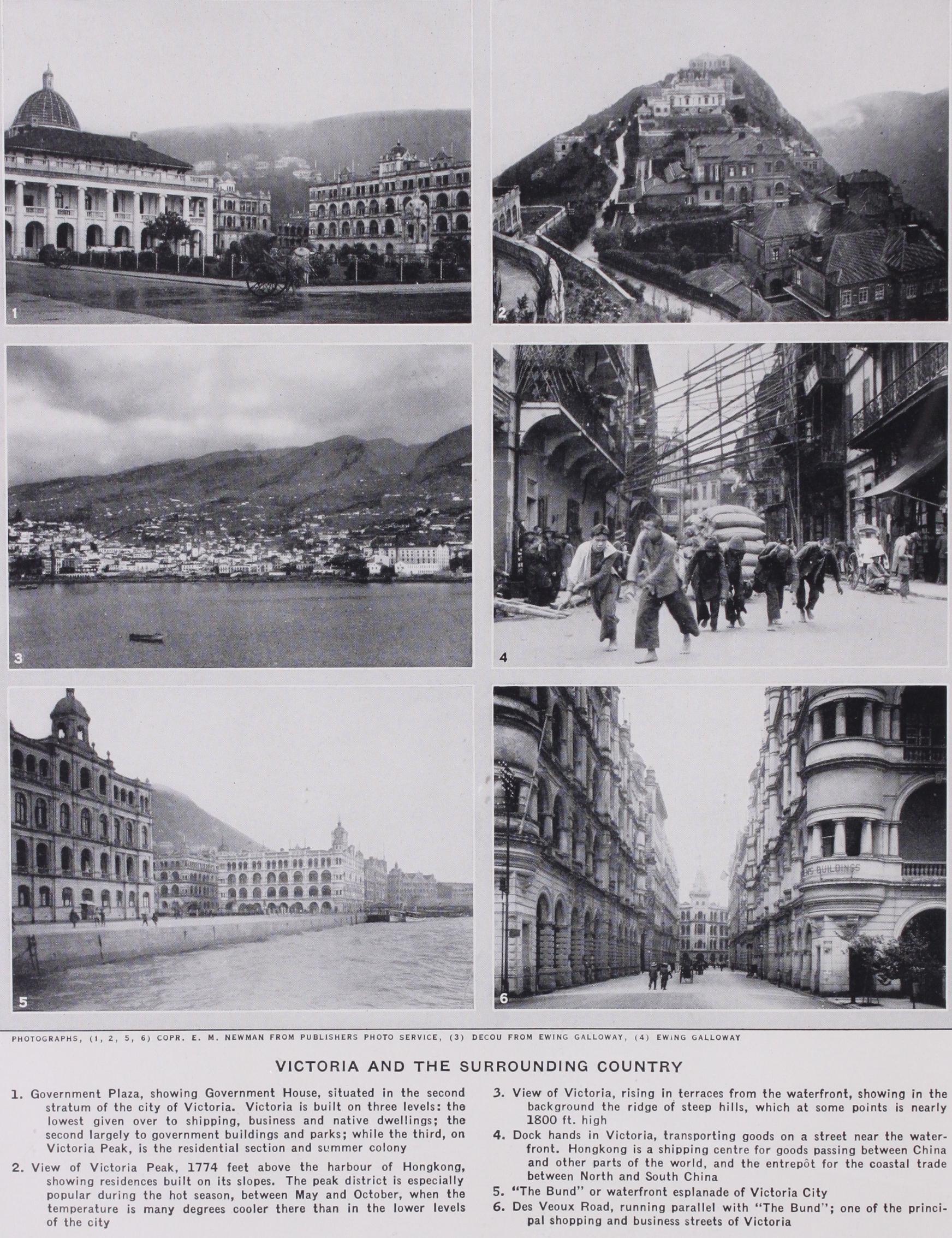

Hongkong island, a detached fragment of the South China massif, is chiefly composed of primary rocks, of which granite occupies about half the total area and forms the basis of the struc ture. The main topographical features of the whole group of islands are largely due to two sets of fracture-lines trending N.E.—S.W. and N.W.—S.E. As a result, the coasts are extremely broken and provide a number of splendid natural harbours. The chief physical feature of the island is an E.—W. range of steep conical hills which rise some 1,500 ft. above the basal plateau, very little of which is suitable for cultivation. Victoria Peak (I,774') in the north-west and immediately south-west of the capital, is the highest point. From the sea, and especially from the fine harbour which fronts the capital, the general aspect of the city rising in hill-side terraces, is very attractive.

Hongkong lies just within the tropics and had formerly the reputation of being unhealthy. This has been largely remedied by sanitation but some districts of the colony are healthier than others, owing to differences of altitude or aspect. The Peak in Hongkong island is usually 8° F cooler than Victoria below and so affords a valuable sanatorium for the white population. The pre vailing winds throughout the year are easterly. The mean July temperature is 82° F, but that of February only 57.7° F, the relatively cool winters being due to north-east winds. The mon soonal rainfall increases to a June maximum of 16.3" with a sec ondary maximum in August. The mean annual rainfall is 90 inches. Typhoons account for most of the climatic eccentricities and at times cause great damage to property and shipping.

Prior to the British occupation Hongkong was a desolate island, occupied by a small fishing population, and was a notorious haunt of pirates. It was during the "Opium War" of 1839-42 that its harbour, which since 1821 had sheltered opium vessels, was utilized as a naval base for British ships. Barren and unhealthy as the island was and lacking natural resources, the great commercial and strategic significance of this deep, sheltered harbour, ten square miles in area, possessing east and west entrances and lying right on the path of the chief trade route to China, was quickly realized. Its cession to Great Britain in 1841, confirmed by the Treaty of Nanking (1842), was one of the chief results of the war and, despite the fact that owing to the lack of other resources its development was for a long time purely commercial, it has grown in less than a century to be one of the world's greatest ports.

The history of Hongkong since 1842 has been inseparably con nected with the development of its trade and this, fostered by a free-port policy, has grown with the progressive opening up of China's foreign relations. Hongkong's development falls into well defined stages. During the first years of British control opium was the foundation of its trade, but in 1849 the island became the chief centre for the coolie transport-traffic to the gold fields of California and Australia. From 1850-6o Hongkong acquired the nucleus of a settled Chinese population which has proved essen tial to its commerce. A short period of reaction set in with the loss of the raw-cotton trade built up during the American Civil War, but in 1869, the opening of the Suez canal enlarged its sphere and brought it into closer touch with Europe. While the tonnage of ships calling at Hongkong doubled between 1860 and 1870, it quadrupled between 1870 and 1880, following the opening of the canal.

It had been apparent from the beginning that Hongkong was menaced owing to its proximity to the mainland. A special source of danger was the Kowloon peninsula which dominated the har bour and threatened Victoria. Following the 2nd Opium War, Britain obtained (186o) the cession of Kowloon peninsula and Stonecutter's island ; but Hongkong was not completely defensible so long as the whole harbour was not contained within British territory. Hence during the struggle for concessions, at the end of the century, Great Britain obtained (1898) a 99 years' lease of the mainland as far north as the Shumchun river and of the islands around Hongkong within the limits of 114° 5' and 114° 18' E. and 22° 17' N. This involved the control of a relatively wide stretch of sea, and so provided additional security.

Although both territorial extensions were acquired on strategic grounds, they have since proved useful in other directions for Kowloon is now an outlet for the overflow population of Hongkong and a field for its industrial development while the New Territories are a potential source of raw materials for its trade and industry. Thus the three units are supplementary, and together make up the complex but compact unit of Greater Hongkong.

Hongkong for Chinese customs purposes is regarded as a for eign port but its essential trade function is to serve as a point of transhipment for goods passing between China and the outer world, and at the same time act as an entrepot for the coastal trade between north and south China. Although it has commercial relations with all parts of the world, the Far East trade in 1922 accounted for no less than 95% of its exports and 66% of its im ports. The nature of this trade is well illustrated by the chief commodities—rice, sugar, cotton yarn, tin and coal. In recent years Hongkong has been the principal centre of rice distribution in the world. The main source of supply is French Indo-China, which in 1922 stood second in the total import and export trade of Hong kong and is mainly an exporter of foodstuffs and raw materials in return for Chinese and foreign goods. The rice-exports of the port, whose value in 1924 amounted to £9,681,958 are chiefly to China, for Hongkong, lying between the chief supplier and consumer, handles 85% of China's total rice-import. Rice is exported to a smaller extent to the United States, Cuba and the Philippines while Japan is supplied only when her crops fail. Hongkong is also, after Java, the chief sugar-distributing centre of the Far East. The bulk of the imports, largely determined by the colony's refining indus try, comes from the Dutch East Indies (74%), and most of the remainder from the Philippines. The total exports in 1924 were valued at China takes about 7o% of the refined and 75% of the raw sugar exports. Cotton-yarn is usually third in both the import and export trade of Hongkong. It is imported from India (57%), Japan, North China, the United States and Great Britain, to the value of about £4,000,000. Of the total ex ports South China takes about 5o% and French Indo-China 4o%. Japan is increasing its hold on the cotton piece goods trade, for merly almost monopolized by Britain. After Singapore, Hongkong is the chief tin market of the Far East. This commodity comes chiefly from Yunnan, via Haiphong, and is sent to Hongkong to obtain the best market and the best facilities for exportation, its chief destination being America, and to a lesser degree, Japan. The total value of tin-exports in 1924 was £1,774,049. The importation of coal, great as it is, is only sufficient to meet the needs of the coastal and local traffic. Japan supplies about 65% of the total imports, of which only 25% is re-exported mainly to neigh bouring ports. The importation and exportation of raw opium was prohibited by Ordinance No. 3o of Dec. 21, 1923, and there is now no legitimate movement of opium in the colony.

Although Hongkong's commercial relations embrace the whole field of China, its real trade-sphere in that country radiates from a centre in the Canton delta into Indo-China and East Yunnan, and as far north as a line passing west from between Amoy and Foochow along the main watershed into Kweichow. With Canton, the chief collecting and distributing centre for all the foreign trade of the interior of South China, Hongkong's relations are especially close. Since ocean vessels cannot get beyond Whampoa, commodi ties for Canton are transhipped at Hongkong and sent up the river in small vessels. Thus Hongkong is in a sense the deep-water port of this ancient outlet of south China. In 1922 out of Hongkong's exports to China, amounting to about 6o% of her total exports, Canton took 53%, to the value of £ 17,000,000. Hongkong in that year supplied 94% of Canton's imports and took 99.5% of its exports, the silk-trade accounting for 68% of the latter. So too, more than 9o% of the total trade of the southern ports of Kwang tung is with Hongkong, which is also the chief source of foreign goods for Swatow and Amoy. Imports from Hongkong reach as far as Hankow, but the export trade of the Yangtze basin is in the hands of Shanghai. Hongkong can, however, compete more suc cessfully in north China where the demand for its refined sugar is the chief factor in the trade, and it is probable that the completion of the Canton-Hankow railway will increase its contacts with the Yangtze lands.

Next to the Far East, the United States looms largest in Hong kong's trade relations, receiving about 3.5% of its exports and sup plying 16% of its imports. Hongkong's chief export to the States during the period 1913-18 was rice but tin is now the chief com modity. In return the United States is the main source of its imports of flour and kerosene, the value of which in 1924 was £2,309,925 and £1,594,806 respectively. Britain's share in the trade with Hongkong is relatively small; the latter can, in no sense, be regarded as a centre of British Imperial trade, for its sphere is essentially the Far East and the Pacific.

Hongkong is tending to become the centre of Japan's growing trade with south China, and it is the point of transhipment in the trade between Japan and Indo-China. The latter exports rice and tin (originally from Yunnan) via Hongkong to Japan, and in re turn receives cotton yarn and manufactured goods. There is also a steady trade with the Straits Settlements, because exports are mainly Chinese foodstuffs and manufactured goods for the Chinese colonies in Malaya.

The Total Trade of Hongkong (excluding Treasure) Depending as it does on the changing demand and supply of the Far Eastern market, Hongkong's trade is liable to great fluctua tions. In the boom period after the World War the import trade more than doubled between 1918 and 1920, but this was followed by a marked decrease, due partly to the continued fall of exchange on the tael, partly to the troubled internal conditions of China and the political and trade friction between Hongkong and Canton. Trade in 1925 and 1926 was hurt by the Cantonese boycott.

The total shipping entering and clearing at ports in the colony during 1924 amounted to 764,492 vessels of 56,731,077 tons. Of these, 56,765 vessels of 37,770,499 tons were engaged in foreign trade. The growth of Hongkong's shipping after the war was re markable, the tonnage in 1923 exceeding that of 1918 by no less than 24,000,000 tons.

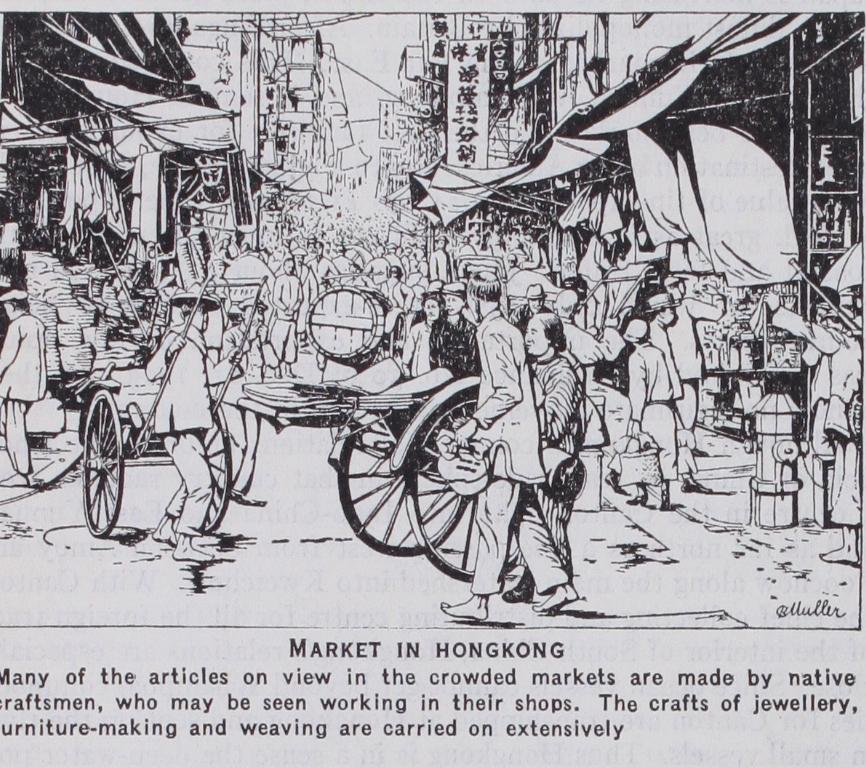

Hongkong has become the chief centre of the Far East passen ger service and is a port of call for the largest liners in the serv ice. River steamers, launches and junks trade with Macao, Can ton and the smaller delta ports of Kwangtung and as far up the Sikiang river as Wuchow where they connect with a fleet of Chi nese motor-boats. In colonial waters the traffic is very heavy, varying with the amount of ocean shipping. Steam launches in the local trade in 1923 amounted to 17,400,000 tons, while junks in both local and foreign trade totalled 3,900,000 tons. These river and harbour fleets are vitally important to Hongkong since its chief markets lie in the adjacent delta-lands of the Si-kiang and the hinterland of Canton. Although commerce remains the life blood of the colony, Greater Hongkong has in recent years de veloped considerable industrial and agricultural activities. The industries depend on trade for most of the necessary raw materials and so cover a wide range—tin- and sugar-refining, rice polishing, furniture-making, ship-building and engineering, the manufacture of cement, paper, rope, glass, soap, ginger, canned and knitted goods. The chief industries are controlled by Europeans but the factory system under purely Chinese management is proving suc cessful. Local production of raw materials, wherever possible, will greatly assist further industrial development in the colony. The island itself has no valuable mineral resources except building stone, but the New Territories contain deposits of copper, tin, iron, wolfram, silver-lead and limestone. These may prove work able after initial expert investigation and the revision of the present Mining Ordinances of the colony.

The chief economic value of the New Territories, however, lies in their agriculture in spite of the limitations imposed by the high relief. Rice supplies the needs of the whole peasant population and occupies 9o% of the total cultivated area. Sugar is at present the only important commercial crop. There are, however, great possibilities for fruit-growing, especially if the hill-sides are ter raced. The pineapple crop is already considerable, and is the basis of a growing native canning-industry. Road-making is help ing to improve the facilities for marketing the garden-produce of the New Territories. The great extent of hill-pasture also affords opportunities for stock-raising. While Hongkong itself is of small agricultural value, afforestation has converted the "desolate rock" of 1842 into a fairly well-wooded island; the main objects of the forestry policy have been soil-preservation, water-conservation, revenue and beauty. The chief tree is the pine but several others, including the camphor and eucalyptus, have been successfully acclimatised. Oil-producing trees are receiving especial attention.

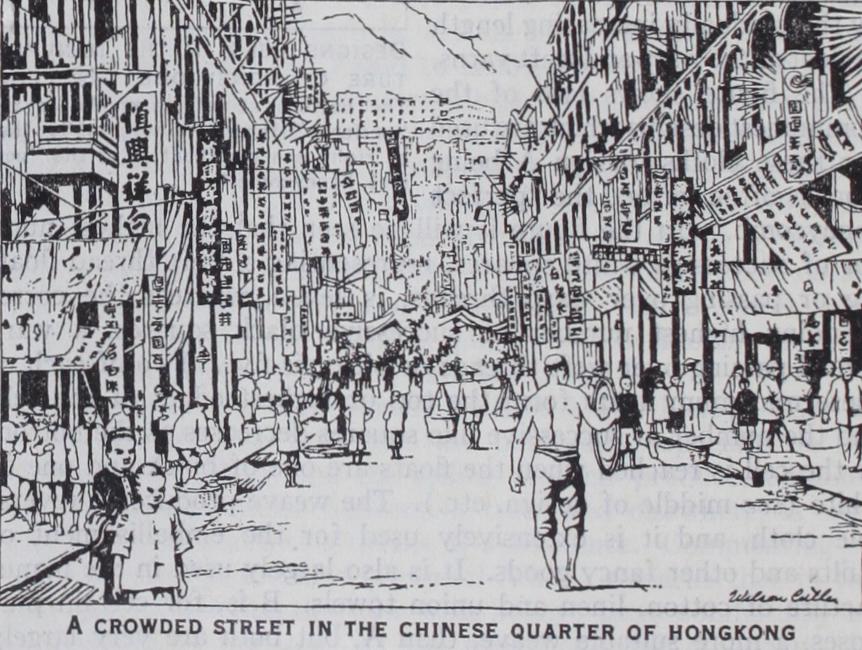

In addition to the Chinese roads, the best of which are paved, Hongkong island contains a network of good macadamised roads which are essentially defensive and are of small economic value. They take the form of a circular route following the coast with cross-connections using the hill-gaps. The construction of a rail way from Kowloon to Canton was one of the conditions accom panying the lease of the New Territories. The through route was opened in 1911 and connects with Hongkong by ferry from Kow loon. There are no other good external communications. Not least among the many important economic aspects of Hongkong is its pre-eminence as a banking centre. The circulation on Dec. 31, 1924 of notes of the three banks having authorized issues amounted to $62,511,402 and the total amount of coin in circula tion was $17,864,370.96. The revenue of the colony for 1924 was $24,209,640 and the expenditure $26,726,428. During the period 1915-24 the assessment of the whole colony rose from about 144 to over 22 million dollars.

The population of Greater Hongkong was in 1931 made up as follows: Foreign Civil Community, 19,369; City of Victoria, 3S8, Villages of Hongkong Island, 41,156. New Territories, 97,781; Population Afloat, 68,721; Total Chinese Population Total Civil Population 840,473. The boat-population which centres in Victoria harbour, and the agricultural population of the New Territories are both indigenous and form distinct and stable elements in what is, as a whole, a fluctuating and changing native population. Thus in 1924, no less than 129,8S9 emigrants left the colony, more than half of whom were bound for the Straits Settle ments, but these were balanced by 130,194 new arrivals. Immi grants from the. Canton delta account for 76% of the total popu lation of Hongkong and Kowloon. The industrial element is ap preciably growing, especially in Kowloon. The colony is faced with the social problems involved in the new industrialism of the Far East and has to its credit the first factory regulations govern ing the conduct of industry and the employment of woman and child labour, following the report of a special enquiry in 1921-2. A good deal of pioneer educational work has also been done. In 1924 the total number of children and schools in the colony was 47,933, of whom nearly 15,000 were at English schools. The edu cational system is crowned by the University of Hongkong, which in the face of serious financial difficulties, offers advanced instruc tion in most forms of Western science and learning, and, as the only British university in _ the Far East, makes a wide appeal.

Acquired in the first instance as a defensive base for the China trade, Hongkong has become by the stress of events a vital fac tor in the strategic geography of the Pacific. As a naturally strong naval base and the focus of British interests in the Far East, its status in any regional agreement concerning the peace of the Pacific is of world-wide significance. One of the most important results of the Washington Conference of 1921-2 was an agreement by the United States, Great Britain and Japan re specting the non-fortification of naval bases in the Pacific, as part of which Great Britain undertook not to develop a first-class naval base at Hongkong. It has been claimed in consequence that its strategic security in case of a naval war will in part depend on the efficiency of Singapore. (P. M. R.)