Horse-Racing and Breeding

HORSE-RACING AND BREEDING. is mentioned in the Iliad (xxiii. 212-650). It was also known to vari ous Oriental peoples at a very early date. Details, however, are few and it is doubtful whether horse-races as the West knows them to-day existed at all among early peoples.

It is not possible to say with any conviction or certainty when horse-racing actually began in England. The writers and histori ans of old were vague and indefinite in the extreme. Probably it began with the origin of the horse itself in Great Britain. For if human nature and the sporting instincts of the people who lived centuries ago had any relation to what they are understood to he to-day, then it is certain that one man matched his horse or pony with another man's for a wager of sorts, perhaps, indeed, for no wager at all but merely to put a dispute to the test. It really matters little. We are entitled to assume that human nature has changed little if at all through the ages, and that they probably did the same then as we do now, according to their limitations, which we may be sure were determined for them by the very definite limitations of the early English horse. What we are certain of is that racing has been carried on for hundreds of years; and that the horses that came over with the Norman conquest were big animals capable of carrying heavily armoured men and inevitably assisted in imparting to the later English horse that size which has been increasing with its steady evolu tion.

Kings, prime ministers, peers of the realm, and commoners of varying degree figure as owners in the long history of racing in this country. The reign of Henry VIII. is generally accepted as marking the first definite beginning of anything like organized race-meetings, for it was in that period that racing is believed to have taken place at Chester on what was called the "Rodhee" or "Roody" and must certainly be what is now known as the Roodee on which a three-day meeting each year flourishes to this day. Queen Elizabeth, according to Nichols' Progress of Queen Elizabeth, maintained a breeding stud, and in 1585, accompanied by a brilliant retinue, attended the races at Croydon, as also in 1587 and 1588. The first mention of racing at Doncaster is dated 1600. "Wheatley More," which was probably the Doncaster Town Moor of to-day on which the St. Leger is decided every September, was the scene. Probably the earliest description of a race occurs in Clarkson's History of Richmond (Yorkshire) (1821). It occurred on May 6, 1622, and is reproduced below:— A new maid race upon Rychmond Moor of iiii myles, sett forth and measured by Mr. James Raine, Alderman, and Mr. John Metcalfe, and many other gentlemen and good fellowes the vith of May. And further the said James Raine, Alderman, with his brethren hath made up a sume of xii poundes for to buy a free cupp for those knights, gentlemen or good fellowes that have horses or mares to run, leavyng the cupp free to their own disposition, must make upp the value of the said cupp, to renue the same for the next yeare.

Whereas the names in order as they came this present yeare 1622 was as followeth, John Wagget onely the starter.

Imprimis Sir George Bowes

. . . his horse z.Mr. Hunphrey Wyvell, his tryer.

Mr. Thomas Bowyer .

. . his horse 2.Mr. Christ. Bollmer, his tryer.

Mr. Francis Broughe .

. . his horse 3.Mr. Matt Rymer, his tryer.

Mr. Wansforde .

. . his mare 4.Mr. Anthony Franckland, his tryer.

Mr. Loftus . his horse 5.

Mr. Francis Wickliffe, his tryer.

Mr. Gilbert Wharton .

the last and the 6.Mr. Thomas Wharton, his tryer.

So every party putting xl shillings, hath made upp the stake of xii poundes, for the buying of another cupp for the next year following.

Newmarket.—Although there are the records and a few others which it may not be necessary to enumerate of that early racing it remains a fact that the history of horse-racing in Eng land is really the history of racing at Newmarket since its begin ning. At least this can be made to apply until such time as there came a great organized expansion, but the headquarters of the Turf has always been Newmarket, and especially, of course, following the establishment of the Jockey Club in the years 175o or 1751. James I. may be said to have "discovered" Newmarket and developed it as a sporting centre. Charles I. did much to encourage racing and improve the breed of horses, and there are definite records of the feats of Charles II. on Newmarket Heath. On October 12, 1671, as recorded by Frank Siltzer in "Newmarket," he rode his own horse, Woodcock, in a match against Mr. Elliot (of the Bedchamber) on Flatfoot which the latter won, but two days later the king rode the winner of the plate (being a flagon of 32 price), the other competitors being the Duke of Monmouth, Mr. Elliot, and Mr. Thomas Thin (short for "at the inn" afterwards written Thynne) an ancestor of the Marquess of Bath. In March, 1674, the king, wrote Siltzer, again won the plate, and Sir Robert Carr, writing to his colleagues at Whitehall, says:—"Yesterday his Majesty rode himself three heates and a course, and won the Plate—all fower were hard and ne'er ridden, and I doe assure you the King wonn by good horsemanshipp." In 1740 (George II.) we have parliament for the first time taking cognizance of horse racing. In that year an Act was passed which had for its object the putting an end to a number of country meetings by raising the stakes run for. It was insisted that every horse entered for a race must be the bona fide prop erty of the person entering it, and that one person might only enter one horse for a race on pain of forfeiture. Parliament also settled the weights which horses had to carry. Thus five-year olds were set to carry lost; six-year-olds I 1st; and seven-year olds i 2st. It is interesting to note that enactment, since it was the beginning of the more elaborate weight-for-age scale which is of paramount importance at this day and to which reference is made later. Curious is it to note, too, that the penalty inflicted upon the owner of any horse carrying less than those weights was the forfeiture of the horse and the payment of a fine, in addition, of £200. In those days races were over a distance of four miles and it is not surprising that the racing of two-year-olds was unknown.

The Jockey Club.—At the outset of its existence the Jockey Club originating, as has been said, in 175o or 1751, was con cerned only with racing at Newmarket, but it was inevitable that its embrace should in time extend to all racing in England, there and elsewhere. That authority has now lasted for approaching two centuries. It has stood the test of time and public opinion, which has varied enormously in its attitude to racing. Always, however, the honour and integrity of the Jockey Club have been beyond reproach and criticism, and to that fact the enormous development of the Turf and the inherent love of horse racing in the people is primarily due. In 1752 race meetings were held at about 7o different places, ten of which were in Yorkshire, includ ing, of course, York, where in 1709 there had been a race for a gold cup. In 1789 racing took place at 72 places in England, at three in Wal^•.,, six in Scotland, and 15 in Ireland. Newmarket then claimed ten fixtures in the year; there are only eight to-day —three each in the spring and autumn and two in the summer. To show how racing has grown through the generations it is worth recalling that 1,166 horses took part in flat races a hun dred years ago while to-day the number may be anything between four and five thousand.

English Racehorse Origins.-It may not be inappropriate here to trace the origin of the English racehorse of to-day and note the foundation of the General Stud Book. It is an indisput able fact that thoroughbreds all over the world, in France, North and South America, the countries of Europe, Australia, and the British dominions are all descended from English racehorses; that is to say, they all trace back in direct male line to three Eastern horses which were introduced to this country, viz., the Byerly Turk, the Darley Arabian, and the Godolphin. The last named was either an Arabian or a Barb, but we know that he was imported about the year 1728. Most interesting is it to know that of the 174 Eastern sires which were mentioned in the first volume of the Stud Book, covering a period of over 200 years, only the three mentioned survived to keep their descent intact to this day. The Darley Arabian was imported by Mr. Darley, brother of Mr. Darley, of Buttercrambe (now called Aldby Park), midway between York and Malton. The Byerly Turk was im ported into England by Captain Byerly, whose charger he was through the whole of King William's wars in Ireland, prior to being put to the stud. The Godolphin was discovered in Paris about 1728. It was said he had actually drawn a water-cart. The finder of this foundation horse of the British thoroughbred was Mr. Coke, of Norfolk, who gave him to Mr. R. Williams, by whom he was presented to the Earl of Godolphin. He was a brown bay, standing about 15 hands, and died in The better to show the influence of those three Eastern sires it should be understood that there are three outstanding families through the long history of the British racehorse. They are known as the Eclipse, the Matchem, and the Herod lines. By far the most famous is that of Eclipse, whose name is probably familiar to all having even a superficial knowledge of the early thorough bred horse. Let us glance at the breeding of these horses. Eclipse was sired by Old Marske, who was a grandson of the Darley Arabian. His dam Spiletta had for her grandsire on her own sire's side the Godolphin. Herod's great-great-grandsire was the Byerly Turk, and the name of the Darley Arabian commences the pedi gree of his dam Cypron. The grandsire of Matchem was the Godolphin, his dam having the Byerly Turk at the beginning of her pedigree. Other Eastern sires and mares are concerned with the breeding of Eclipse, Herod, and Matchem, but the three I have mentioned are pre-eminent and they were to remain predomi nant right through the generations. The vast influence of Eclipse cannot be too carefully noted. The ever-famous horse was foaled in 1764, the breeder being the Duke of Cumberland. He was never beaten. To this day the old saying is as fresh and as true as ever—"Eclipse first and the rest nowhere !" The horse won, or walked over for, 26 races and matches, including eleven King's Plates. In 23 years at the stud he sired 344 winners of races worth 1158,047-12-o. Think what a prodigious total it would have been in these days when stakes are many times bigger than they were in the days of Eclipse. His stud fee varied between 20 and 5o guineas. His great descendant, St. Simon, was for nine years at the stud at a fee of 500 guineas, and there are sires at the stud to-day for which the same very high fee is paid.

Two vitally important milestones stand out clear and distinct. One was the publication of the first volume of the General Stud Book in 1781 and the issue of the first Racing Calendar in 1727. At the time of writing Volume XXVI. is the latest. In the first volume 387 mares were included because they were con sidered to be possessed of pure racing blood. In 1891 that first edition was revised and revised again, and all but seventy-eight mares were eliminated. To-day the Stud Book contains the names of over 6,000. The compiler of the first "Racing Calendar" was one named John Cheny, who lived at Arundel in Sussex, and it is said of him that in order to complete his book he rode all over the country to collect his accounts of race-meetings. The title page, as here reproduced, is taken from C. M. Prior's most interesting history of the "Racing Calendar." This, then, is the reading of the title page of that historical first volume: "An hystorical list on account of all the horse-matches run, and of all the plates and prizes run for in England (of the value of ten punds or upwards) in 1727, containing the names of the owners of the horses, etc. that have run, as above and the names and colours of the horses also, with the winner distinguished of every match, plate, prize, or stakes; the conditions of running as to weight, age size, etc., and the plates in which the losing horses have come in with a list also of the principal cock matches of the Kingdom in the year above, and who were the winners and losers of them. London. Printed in the year M.D.C.C.XXVII." It has been made clear that the British thoroughbred of to-day had Eastern sires and mares of Eastern origin for his early ances tors. The singular thing is—at least it may appear singular to some people—that long before the present day the English race horse, due to careful breeding and the marvellous effect of our climate and soil on constitution, bone and general development, would hopelessly out-match the best horse to be found in the East. Indeed, it has been demonstrated here and in India that no weight in reason will bring the two together in such a way as to give the Arabian horse even a remote chance of beating a very moderate thoroughbred. In 1884 the Jockey Club were persuaded by an ardent admirer of the Arab horse to introduce a race for Arabs, which meant reverting to an experiment tried so long ago as 1771. A race entirely for Arabs was brought off at New market and was won by Admiral Tryon's Asil. In the following year this same horse Asil, in receipt of 4st 7 lb. was beaten 20 lengths by Iambic, a very moderate horse owned by the Duke of Portland over a three-mile course at Newmarket. One can understand how the Darley Arabian, the Godolphin and the Byerly Turk were marvels of their day, and no doubt they imparted quality and action to the native breed of the period, but after that our climate and feeding, which are unrivalled for horse breeding and rearing, careful mating and rigorous compilation of the Stud Book have evolved such a horse to-day as could never have been dreamed of at the beginning of the history of the British thoroughbred. Even in the days of that great dictator of the Turf, Admiral Rous, an Arab horse, according to him, would have had no chance even if it only carried an empty saddle! Changes of Method and Outlook.—Looking back on Turf history one must be struck with the vast changes in methods, out look and practices, for things are done now—as, for example, the racing of two-year-olds—that would not have been tolerated many years ago, and many things they did then have been long since abolished and would on no account be revived to-day. Stakes would be raced for in heats over four miles restricted to five-year-olds and upwards and were then opened to f our-year olds. In 1831 they even had time to decide Mr. Osbaldeston's famous Match against Time. That sportsman had made a wager of I,000 guineas that he would ride 200 miles in ten hours. The ground, forming a circle of four miles, having been marked out on and about the Round Course, he started about seven o'clock in the morning and performed the distance in 8 hours and 42 minutes, without apparent difficulty. He changed his horse every four miles, and rode 29 different horses. A bet of ',coo to ioo pounds was laid that he did not perform the distance in 9 hours. Let us look at the British Turf as it is to-day; and doing so it will not be without interest to examine its ramifications, the history of its five "classic" races, the great circle of racecourses which are part of its structure, the conditions under which the sport is conducted and the immensely enhanced value of the modern thoroughbred. We have the Jockey Club still supreme as the governing authority with its reputation as an institution never higher and more respected. It manages its own affairs at Newmar ket as it always has done, while all racing elsewhere must submit to rules which have taken generations to perfect and make applicable to the evolution of the horse and the sport itself. Great names have had to do with administration from time to time. Admiral Rous has been mentioned. King Edward VII., the Earls of Derby, the late Duke of Westminster, the Duke of Portland, Sir Fred Johnstone, R. C. Vyner and the late Lord Chaplin have all played big parts and with them racing was essentially a sport rather than the business which in some cases it is tending to become to-day. Mr. Lowther was fearless and even formidable, which is certainly true of Lord Durham, who died in 1928. They and others have at all times aimed at digging out the wrong-doer and ridding the Turf of those undesirables to whom it has ever been as a power ful magnet. When Admiral Rous died in 1877 there was brought into existence a Rous Memorial Fund, essentially a benevolent affair for the relief of the sick and needy connected with the training and riding of racehorses. To 'this day there are Rous Memorial Stakes run for at Newmarket, Ascot, Goodwood and Doncaster in memory of the Dictator. There are Lowther Stakes, Jersey Stakes, Coventry Stakes, Durham Handicaps and Stakes, indeed many races are named after men who gave the weight of their influence and support to the general welfare of racing. What better example can be quoted than the Derby Stakes? The St. Leger was so named out of compliment to the soldier and sportsman, Colonel St. Leger, who may be said to have founded the race (1776).

The five classic races are confined to three-year-olds, the Oaks and the One Thousand Guineas being restricted to fillies, the Two Thousand Guineas, the Derby, and the St. Leger being open to both colts and fillies. It is unusual for the latter to be entered, and still less usual for them to run, but there are bright conspicuous instances on record of fillies winning the Derby, while they have with some frequency won the St. Leger. It has even happened that a filly has won both the Derby and the Oaks in the same week at Epsom. Signorinetta, bred and owned by an Italian, Chevalier Ginistrelli, who had for some years been settled in this country as an owner-trainer in a modest way, astonished the world in 1908, by winning the Derby at ioo to and then the Oaks two days later. Eleanor in 18or accomplished the rare feat, and the Yorkshire filly, Blink Bonny, did so in 1857. Fifi nella won both in 1916 during the World War, when substitute races were decided at Newmarket. In the Two Thousand Guineas and the Derby colts must concede a sex allowance of 5 lb. to fil lies. The rule in other respects fixes the sex allowance at 3 lb. The "classics" are excellent examples of races which are confined to horses of a certain age. Apart from them there are weight-f or age events in great numbers, handicaps, selling plates (some of which can be for horses of all ages on the weight-for-age scale) , and races for two-year-olds from the time the season opens towards the end of March to when it finishes in November.

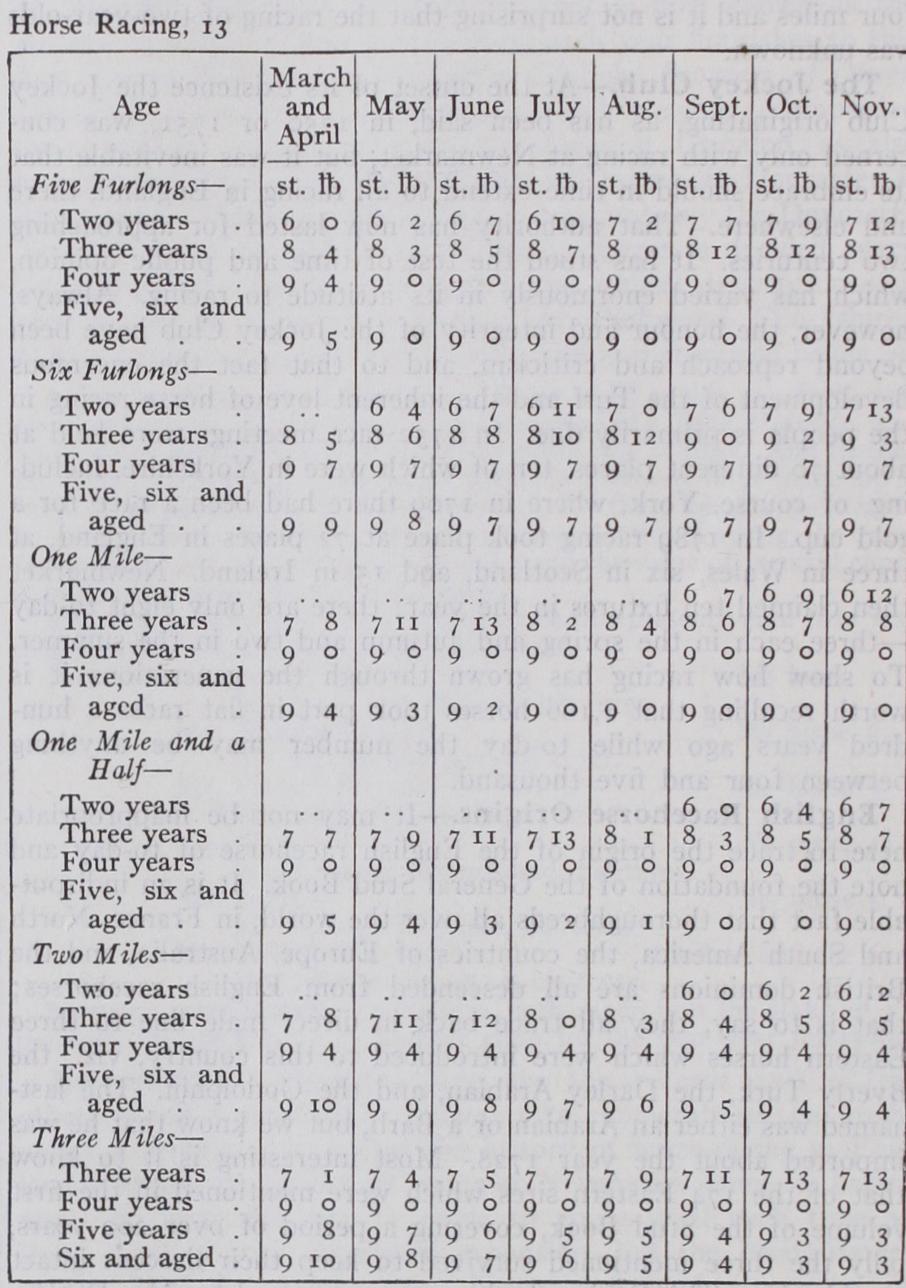

The weight-for-age scale is a fundamental principle in English racing. In a rough sort of way it obtained in the earliest days of racing. The scale was founded by Admiral Rous, and revised by him in 1873, but has been more than once modified in accordance with suggestions from the principal trainers and practical author ities. Horses are called upon to concede weight according to their ages, according to the month in which they race and according to the distance over which they are called upon to run. Thus a two-year-old in March or April over five furlongs would be en titled to receive 2st 4 lb. from a three-year-old, 3st 4 lb. from a four-year-old, and 3st 5 lb. from a five, six or aged horse. The reader will better grasp what is meant from the publication of the present day scale under the Jockey Club rules, which is as follows: A race like that for the Ascot Gold Cup is a good example of a weight-for-age race. Hundreds of others could be quoted, just also as examples might be given of races which have their basis on the weight-for-age scale but which are complicated by penalties for winners of certain sums, a "maiden" allowance for non-win ners, and probably stallion allowances to those horses which have been sired by low fee sires as against those sired by the fashion able high fee horses. The tendency, however, is for stallion allowances to be cut out of the valuable races leaving special events to be created for the progeny of low fee horses. It follows that handicaps are close to the backbone of racing, if, indeed, they are not actually part of that backbone; just as handicaps are the mediums in every competitive sport which aims at bringing the good and the mediocre together. It has been pointed out how the racehorse of to-day would "smother" the Eastern horse from whom he has descended ; that is to say, no weight in reason would bring them together. It is not so with the true thoroughbred. Racehorses do vary enormously in capacity, owing sometimes to one and sometimes to a combination of causes ; physique breed ing, soundness, fitness and temperament are factors of the first importance, but it remains true that the clever adjustment of weights will bring the good, the moderate and the bad horses to gether. It is, therefore, on the many important handicaps of the year that betting is chiefly concentrated. The Derby at Epsom, it is true, excites an amount of betting that is both enormous in extent and world wide in range; but then the premier "classic" is exceptional in every sense.

Handicap Races.—Handicap races which never fail to pro duce a vast amount of betting are the Autumn handicaps at New market known as the Cesarewitch and Cambridgeshire ; the for mer is for long distance horses and the latter for what is known as middle distance performers, for while the Cesarewitch is decided over two miles and a quarter the Cambridgeshire is a race of a mile and a furlong. The Royal Hunt Cup at Ascot, the Stewards' Cup at Goodwood, the Jubilee Handicap at Kempton Park, the City and Suburban at Epsom, and the Lincolnshire Handicap at Lincoln are examples of handicap races which attract much specu lation. Yet that speculation has changed, too, in its character. In years past much of it was done at what was known as "ante-post rates," that is to say, betting would be opened days and weeks before the race—it is so to-day on the Derby and the Autumn handicaps at Newmarket—and long odds would be offered as a bait by the bookmakers. If such odds were accepted the backer had to take a chance of the horse running. If it did not go to the post the wager would be lost. In recent years, especially since the World War, ante-post betting has been steadily declining, probably owing to lack of enterprise on the part of the modern bookmaker, and perhaps also to the backer awaking to the fact that he can get practically as good odds on the day with the cer tainty of getting a run for his money. With the coming into operation of the totalisator (q.v.) ante-post betting will be still further discouraged. The totalisator is essentially a machine that operates and governs the starting price.

Mention, then, has been made of handicap races, which must closely approximate to half the races decided throughout the year. True, there are very few handicaps figuring in the four days' won derful programme of an Ascot meeting. The observation, therefore, must be accepted as having general application. Let it be well understood there is, and always will be, a distinct gulf between what is accepted as "handicap form" and "classic form." Because of that gulf classic form is classic. It is the best, and not un worthy of that description which has been applied to it for ages, certainly during the lifetime of the writer. Frequently are we re minded of what just a touch of classic form can bring about in the deciding of a handicap. A horse that has even been thought good enough to run in a classic race, though unplaced, is regarded as having that "touch." If the records be searched examples will be discovered of horses that gained classic honours being suc cessful in one or other of the important handicaps. I think, as I write, of La Fleche, who won the Oaks, the St. Leger, the Cam bridgeshire and the One Thousand in the same year (1892), of Sceptre who won the Oaks, the St. Leger, the 2,000 Guineas and the i,000 Guineas in 1902 and of Pretty Polly who won the Oaks, the St. Leger and the i,000 Guineas in 1904. Rarely, however, in these days is the winner of a classic race exploited subsequently in a handicap. Such winner assumes too high a commercial value consequent on having gained classic honours for his or her future to be risked in a handicap, which is primarily concerned with betting. There are exceptions, of course, but the common practice is for owners to retire fillies to the stud after their three-year-old careers. Such fillies have gained supreme honours, and there is danger to the stud career awaiting a filly if there should be any thing in the nature of over-racing. Certainly this is the policy adopted by the leading owner-breeders of whom the present Lord Derby may be quoted as an excellent example. The wonderful success of his breeding stud may largely be due to the considera tion he has at all times shown to those high class fillies which have served him well up to the close of their racing careers. An in stance is that of Toboggan, who won the Oaks and the Jockey Club Stakes in 1928. That race in any case was to have been the last of her career, and it was merely an incident, and not a decid ing factor, that she broke down in the race for the Jockey Club Stakes although she won it.

It is even more the custom to guard jealously the subsequent career of a Derby winner. To run the risk of defeat in these times is to accept a heavy responsibility. It has been thrust upon owners by the phenomenal jump in the values of high class blood stock. It is no exaggeration to say that immediately a horse has passed the post as the winner of the Derby he becomes worth a minimum of £5o,000. That is a modest enough figure; it would not be wrong to place it much higher. Felstead, the Derby winner of 1928, though his form preceding the victory had been anything but brilliant, was bid for from America up to £100,000. His owner, Sir Hugo Cunliffe-Owen, being, it need scarcely be said, a very rich man, preferred to keep his horse. Solario did not win the Derby, but he won the St. Leger and the Ascot Gold Cup as a four-year-old. His owner, Sir John Rutherford, refused the Aga Khan's bid of f i oo,000. When the owner of the 1927 Derby winner, Call Boy, died the horse was subsequently sold privately to his brother for £6o,000 and was forthwith sent to the stud rather than be raced as a four-year-old. The Derby had made his reputation to pass on to the stud and entitle him to command a high fee as a first-class sire. Captain Cuttle, who won the Derby of 1922 for Lord Woolavington, was sold to Italy for a sum re ported to be £50,000 after a short period at the stud in England. He would not assume stud duties in Italy until reaching nine years of age. It was a wonderful price for a horse of that age.

The post-war Derby winners have been Grand Parade, Spion Kop, Humorist (dead), Captain Cuttle, Papyrus, Sansovino, Manna, Coronach, Call Boy and Felstead. Captain Cuttle, Call Boy and Felstead have been referred to. The others won for owners who maintain studs and the horses, therefore, retired to them, each commanding a fee varying from three to four hundred guineas. While the owners of Derby winners realize the impor tance of preserving intact the laurels won at Epsom, and while stallion fees remain as high as they do, it will be the policy of such owners to fight shy of allowing their horses to run risks of en dangering their reputations by incurring defeat as four-year-olds. No Derby winner since the war has won the Ascot Gold Cup, which until modern times was looked upon as placing the seal on the racing career of a classic winner just as it did in the cases of King Edward's Persimmon, Isinglass, La Fleche, Bayardo, Prince Palatine and others. Grand Parade, Manna and Call Boy were not trained as four-year-olds. Only Spion Kop even ran for the Ascot Gold Cup, and he finished third to two handicap horses in a poor year. The tendency is for Derby winners as f our year-olds to be concentrated on short distance races, such as the Coronation Cup, a mile and a half race at Epsom, and if entered— as they usually are—then run for the Eclipse Stakes (1 a m.) at Sandown Park and probably the Jockey Club Stakes (ii m.) at Newmarket in the autumn. The inference is that the stamina of the modern thoroughbred and the constitution to withstand a strenuous training for a Cup race of 21 m. at Ascot are doubted.