Horse

HORSE, the name given to the well known domestic mammal, Equus caballus, and its wild representative, Equus przewalskii; the term is also used to include various fossil species and some times, more widely, for the whole family Equidae (q.v.).

Despite a great deal of antiquarian research and much ingeni ous speculation there remain a good many unsolved riddles con nected with the origin and early history of the horse. The most complete series of fossils has been found in America. It appears, however, that the real birthplace of the tribe was in Asia, and that North America was populated by successive waves, which crossed over by the land-bridges existing in Tertiary times. (See EQUIDAE.) Horses survived in North America throughout the Pleistocene period, but at the end of that epoch the whole tribe died out, and the continent was not repopulated until the time of the Spanish occupation. Probably the same is true as regards South America. We can only guess at the cause of the extermina tion of the American horse. Food or climatic conditions can hardly have been concerned, for the other large herbivorous ani mals of the prairie survived and multiplied—the bison for ex ample. Perhaps the likeliest explanation is that some insect-borne disease, like the tsetse fly disease of Africa, broke out and spread before the race had time to acquire immunity.

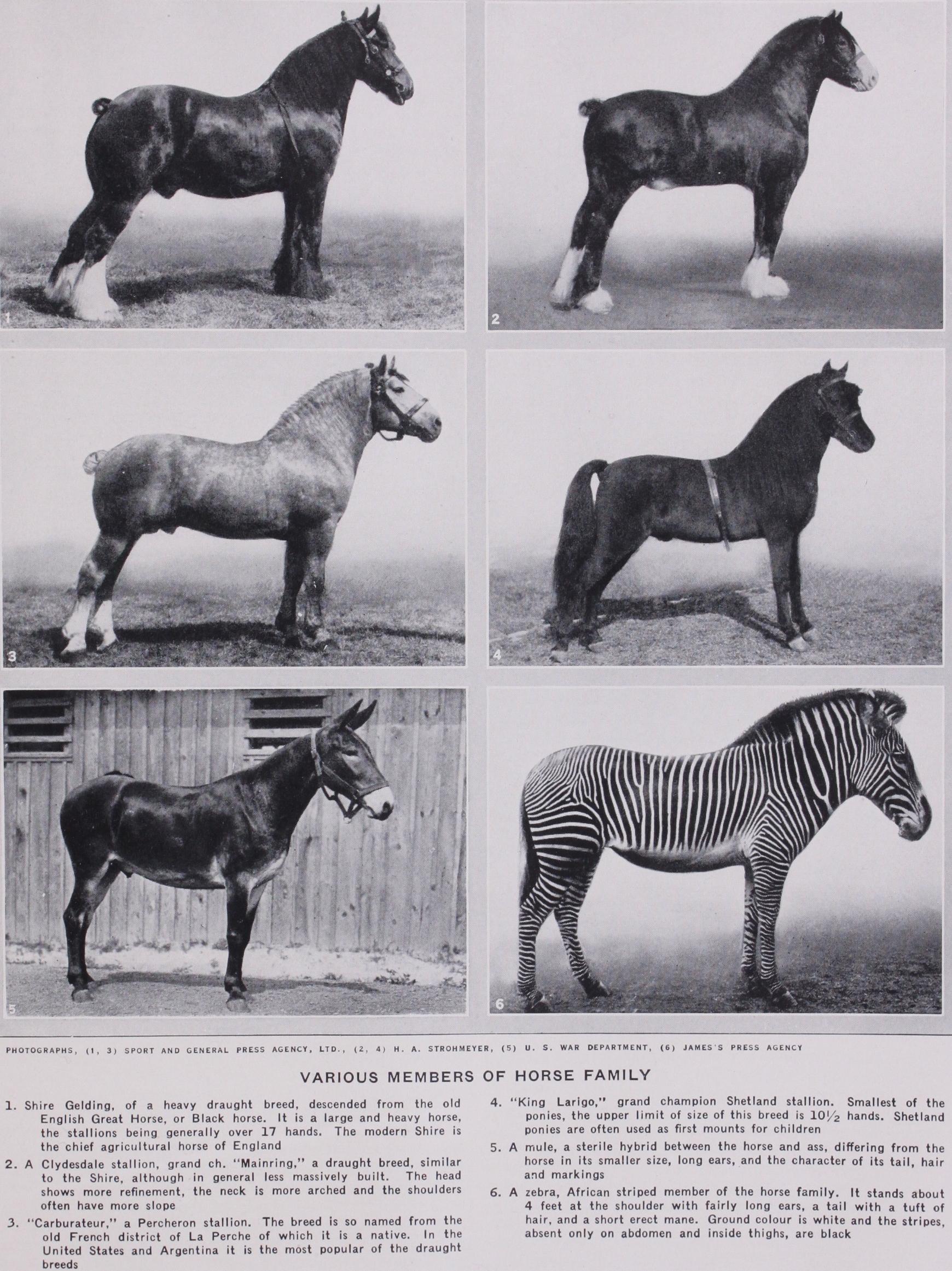

The other members of the Equidae (asses and zebras) are de scribed in separate articles. There is no question of their specific distinctness from the horse. Hybrids of all kinds are easily bred, but there is no authentic case of fertility either in mules or in zebra-horse or zebra-ass hybrids.

The Wild Horse.

The only truly wild horse now in existence is that known as Prejvalsky's horse (Equus przewalskii), named after the Russian explorer, to whom was presented, in 1879, the first specimen known to science. This horse, or rather pony, is found in the Kobdo district of western Mongolia. It lives in small herds of five to 15 head, each under the leadership of an old stallion. In 1902 Karl Hagenbeck of Hamburg led an expedition to the Gobi and succeeded, with the help of some 2,000 Kirghis whom he mobilized, in capturing 32 foals. From these a good many specimens have since been bred, and Equus przewalskii has become a familiar object in zoological gardens. An average speci men is about 12 hands (4ft.) high. The head is very large and rather ungainly, with a small eye and generally a rather wicked expression. The mane is short and erect and the forelock want ing; the tail, too, is rather mule-like, with short hair on the upper part of the dock ; the feet are rather narrow, as in the asses and zebras, but the ears are quite short, and there are, as in most horses, callosities or "chestnuts" on all four legs. The colour is dun, darker on the back and legs, but becoming whitish on the under parts of the body. There is also a conspicuous light col oured ring round the muzzle and a black "eel-mark" on the back. The species interbreeds quite freely with domesticated ponies and the hybrids are fertile. Although Equus przewalskii is undoubt edly a horse, it is rather a primitive type, being less sharply dif ferentiated from the wild asses than are the domesticated forms. No competent authority has ventured on any precise theory about the relationship of the wild species and our modern domesticated breeds. That Prejvalsky's horse represents the common ancestor of all the latter is highly improbable.

Wild horses were very common in Europe during the Old Stone age, and were hunted and killed for food by Palaeolithic man. Stacked in front of the cave of Solutre, near Lyons, there were found the bones of several tens of thousands of horses, all slain presumably by the inhabitants of the cave, who could scarcely have numbered more than half-a-dozen families. That the horses were wild seems likely from the fact that they were all killed young, mostly indeed as foals; and that they were used for food is clear from the circumstances that the remains are completely dismembered and the long bones split open for their marrow. Domestication.—The wild horse is a denizen of the dry open steppes; it is therefore understandable that the improvement of the climate and the consequent increase of forest which marked the New Stone age in Europe should have led to a decline in the horse population. In any case bones of horses are rarely found in Neolithic deposits, which contain plentiful remains of oxen, sheep, goats, pigs and dogs. That all the latter species were domesticated at this time is beyond doubt ; and the remains of the wild ox and wild boar are easily distinguishable from those of their domesti cated relatives. The evidence as regards the horses is not very conclusive, but most probably these were wild. Bronze age de posits, on the other hand, contain plentiful remains of the horse as well as occasional bits and other accoutrements. In Babylonia the horse first appeared about 2000 B.C. It was introduced into Egypt by the Hyksos or shepherd kings who came from the north and east of Syria and conquered Lower Egypt in the 17th century B.C. In both these cases, it is to be noted, the horse was preceded by many centuries by the ox and the ass. From these facts and a few other scraps of evidence one may picture the first domesti cation of the horse as occurring in central Asia. Probably it was accomplished by a people of nomadic herdsmen, to whom the con venience of riding would be obvious. Sooner or later the mounted nomad came to realize the measure of his advantage over the man who travelled and fought afoot, and was encouraged to wander further afield, conquering as he went. In any case the horse (either as a charger or yoked to a chariot) became in very early times an important factor in war. The use of horses for the workaday purposes of transport and tillage is comparatively a modern development; in Britain, for example, oxen were the common plough animals until the end of the i8th century. Horse flesh seems to have been eaten by certain peoples throughout his toric times and is still consumed in considerable quantities in several countries of Europe. Mares' milk, especially in the fer mented form of koumiss, is used as a beverage by the Kalmucks.

On the subject of the origin and classification of modern breeds of horses there is no general agreement. Probably the whole of the oriental light-legged group, including the Arab, Barb and Turk, and indeed all the native races of Africa and Asia, are to be regarded as the descendants of one original Asiatic ancestor. This type was introduced into Europe by two routes—the one from Asia direct and the other via Africa and Spain—in early historical times, and played an important part in the formation of the light legged breeds of western Europe. (See HORSE-RACING.) It seems necessary to suppose that at least one other sub-species of horse was separately domesticated, a European forest type with large bones and broad feet, heavily built and probably hairy legged. This gave rise in particular to the early Flemish heavy horse, which in turn played an important part in the evolution of other heavy breeds like the Clydesdale and Shire. Prof. Cossar Ewart makes a third original group of the Celtic ponies, and pos tulates a separate wild ancestor for these.

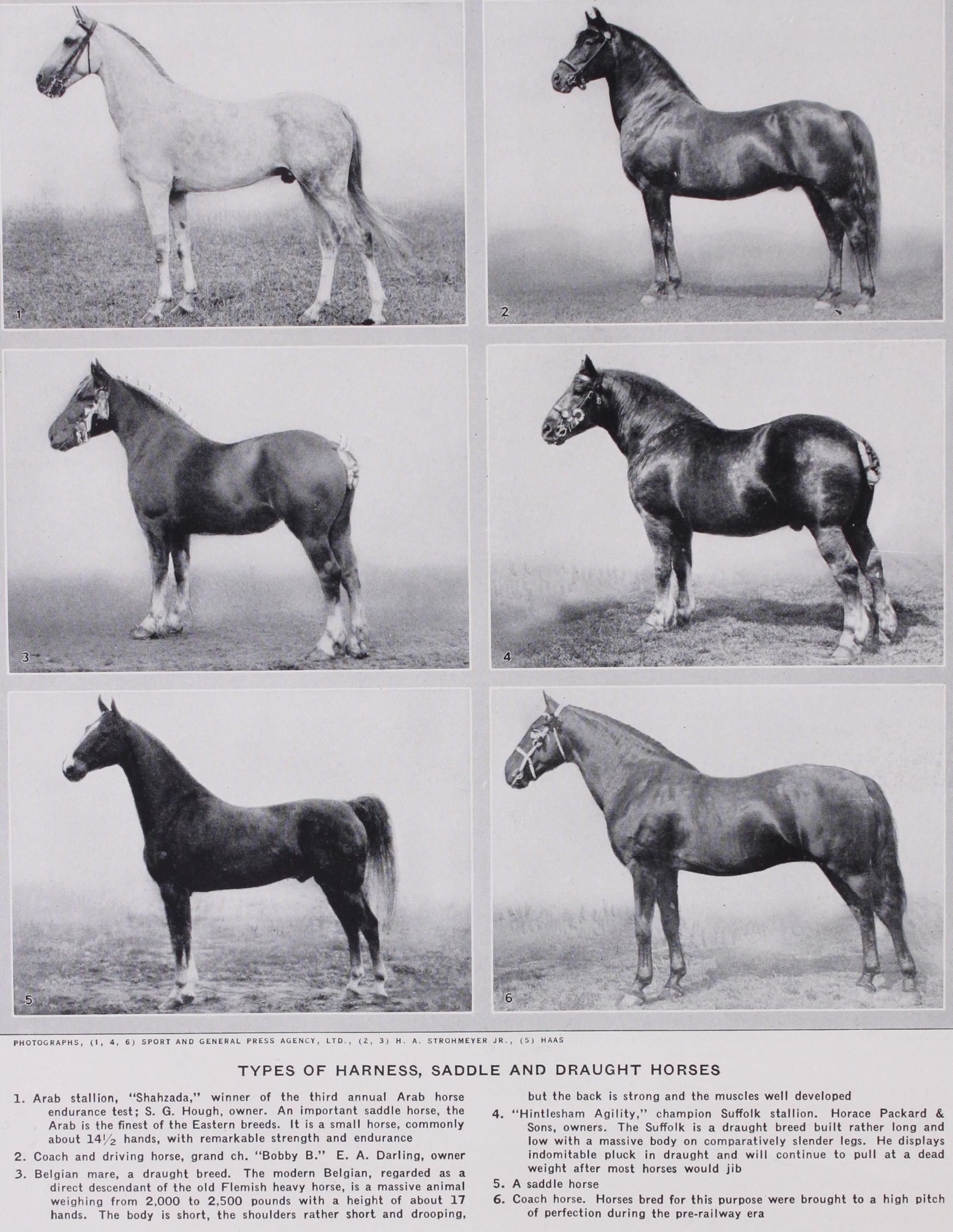

From the point of view of the practical horseman the most satisfactory classifications are those based on utility considera tions, the chief groups being heavy draught, harness and saddle. The two last are further divided, according to size, into horses and ponies, the line of distinction being drawn at about 14 hands.

The most important of the heavy draught breeds are the Belgian, Shire, Clydesdale, Suffolk and Percheron.

Belgian.—The Belgian is regarded as the direct descendant of the old Flemish heavy horse, which was held in high repute dur ing the middle ages as a charger. The modern horse is a massive animal, sharing with the Shire the distinction of reaching the greatest weights. Stallions in full flesh quite commonly weigh from 2,000 to 2,5001b. and occasionally more. The height is gen erally about 17 hands in the male, and 16.1 or 16.2 in the mare. The body is short, the shoulder often rather steep, and the quarter short and drooping, but the back is strong and the muscles every where strongly developed. The legs carry little long hair or feather, and the bone is somewhat round; the head shows little refinement and the temperament is rather sluggish. The Belgian is a useful agricultural horse and a capital animal for heavy dray work. The colours are various—bay, chestnut and roan being common.

Shire.—The Shire is descended from the old English Great horse or Black horse, which was valued in olden times principally for its ability to carry the enormous weight of the armoured knight. Various kings of England, from John to Henry VIII., were at considerable pains to foster the breed, and in particular to maintain its size. The Great horse was descended in part from the pre-Roman horses of the country and, in part, from larger and finer stock introduced mainly from Flanders. The modern Shire is the chief agricultural horse of England, occupying most of the country except the eastern counties and the extreme north, which are given over to the Suffolk and the Clydesdale respec tively. The Shire is a large and heavy horse, stallions being gen erally over 17 and occasionally reaching 18 hands. The back is short and strong, the quarters heavy and powerful, and the whole body both deep and wide. The bone is large and the legs are cov ered with abundant long hair. Despite his weight the Shire is an active horse, trotting freely and easily when required. The tradi tional black colour is now less common than bay and brown.

Clydesdale.—The Clydesdale dates from the early part of the i8th century, and originated in Lanarkshire from crosses between the old local breed and horses introduced from England. Some of the latter were of pure Flemish stock, while others were of the early Shire type. The Clydesdale is of similar height to the Shire, but the general build is less massive, the legs being proportion ately longer and the body neither so deep nor so wide. The head shows rather more refinement, the neck is more crested and the shoulder has often more slope, but the back is commonly longer and less strong. The bone, too, is smaller, and the "feather" or long hair is less abundant, being confined to the back of the leg. Broadly, it may be said that the Shire is stronger and has more endurance in heavy work than the Clydesdale, but the latter is somewhat faster, more agile, and more mettlesome. Clydesdales are of all the ordinary colours, bay and brown predominating.

Suffolk.—The Suffolk is less widely distributed than the Clydes dale and Shire, but is the common farm horse of Norfolk and Suffolk and of parts of the adjoining counties. Its origin is obscure, but it seems to be related to the other heavy breeds. The colour is uniformly chestnut and the limbs are free from long hair. The build is rather long and low, with a massive body on slender-looking rather than slender legs. The height is nearly a hand less than that of the Clydesdale, but the weight is often quite as great. The Suffolk is a hardy and long-lived horse, con tented with plain fare and easily kept fat. He is also remarkable for indomitable pluck in draught, and will continue to pull at a dead weight long after most horses would jib.

Percheron.—The Percheron is so named from the old French district of La Perche, to which it is native. This district forms parts of the modern departments of Orne, Eure et Loir and Sarthe. The breed contains a good deal of the same Flemish blood as the other heavy draught breeds, but modified by crossing with the Arab. Bef ore the railway era the Percheron was bred largely for the stage coach, and although it has since those days been greatly increased in weight it is still hard limbed and active and able to keep up a steady trot for a considerable distance. The head is leaner and more refined than that of any other heavy draught breed, the ribs are very round and the feet shapely and sound though comparatively small. The height is about 16.2 hands in the male, or comparable to that of the Suffolk. The colour is most commonly some shade of grey, but black and bay occur. In the United States and Argentina the Percheron is the most popu lar of the draught breeds.

Harness Breeds.—Harness horses may be divided into two main types. On the one hand are breeds like the Hackney, the Yorkshire Coach, the Hanoverian and the Oldenburg, of consider able weight and strength and generally with high and stylish ac tion ; on the other hand, there is the light roadster type, repre sented by the American Standard Bred, in the breeding of which the main emphasis has always been placed on speed. The Hackney originated in the eastern counties of England during the period about 1800 ; an old local trotting breed, which formed the basis, being improved by the infusion of Thoroughbred blood. The Hackney was brought to a high pitch of perfection, as a strong and fast coacher, during the pre-railway era. Thereafter increas ing attention was paid to symmetry and to stylish action and the breed supplied most of the fashionable high stepping carriage horses of Victorian days, but with the advent of the motor-car it lost a good deal of its commercial importance. The Hackney is a horse of 15 or 16 hands in height, with sloping shoulders, some what rounded quarters and hard, clean legs. The chief gait is the trot, in which considerable speed is combined with high knee and hock action. The Yorkshire Coach and Cleveland Bay are related breeds, somewhat taller and stronger than the Hackney, and with less extravagant action. The former is lighter in build and shows more Thoroughbred influence than the latter. The Cleveland Bay is indeed stout enough to be used for ordinary farm work ; crossed with a Thoroughbred of suitable type it often produces an ex cellent weight-carrying hunter. The American Standard Bred, like many other breeds of light horses, owes a good deal to the English Thoroughbred; it has, however, been bred all along to trot or pace rather than to gallop. In the trot the legs are moved in diagonal pairs, i.e., the right f ore and left hind feet leave and meet the ground simultaneously. In the pace the two legs on the same side move together, as in a trotting camel. Most Standard Bred horses show a natural preference for one of these gaits, but can be easily trained to the other. Trotting and pacing matches run in "sulkies" and on hard cinder tracks have long been the popular form of racing in the United States. The speed attained is, of course, less than that reached by a galloping Thoroughbred, but is nevertheless very fast. The trotting record for the mile is just under 2min., and the pacing record is nearly 5sec. less. Saddle Horses.—The most highly improved of the world's saddle horses are probably the English Hunter, the Arab and the American Gaited Saddle horse. The Hunter is a type rather than a breed. Many horses that are ridden to hounds are "clean bred," that is to say Thoroughbred. Others are the progeny of light cart or Cleveland Bay or half-bred or hunter mares by Thoroughbred sires, while others are of Hunter blood on both sides. Where, as is usual, a Thoroughbred sire is used for hunter breeding it is im portant that he be of large bone, short legged and with plenty of substance. The long-legged and "weedy" type of horse that is often successful as a flat racer is useless as a sire of commercial saddle horses, at least of those of the more valuble weight-carry ing type. A good hunter must be able to show a fair turn of speed, must have strength and endurance enough to carry his rider for a long day across country, and should be comfortable to ride and easy to control in any of the four recognized gaits, the walk, trot, canter and gallop. The importance of hunter breed ing is greater than that of hunting, for the bulk of cavalry and other riding horses are of the hunter type and are supplied from the same sources.

The Arab.—The Arab, though by no means the most ancient of the Eastern breeds, is the most highly improved, and is that which has exercised the widest influence on the horse-flesh of the world. The Arab is a small animal, commonly about 544 and rarely ex ceeding 15 hands in height. The head is full of character and in telligence, with broad forehead and prominent eyes and nostrils. The shoulders are well sloped and the back short and strong, but the wither tends to be somewhat broad and low. The quarter is long and very level, the limbs hard and clean, the pasterns sloping and the feet small but strong. The common colours are white, grey, bay and chestnut, black being somewhat rare. The Arab has remarkable strength for his size and his endurance is rightly proverbial, but his speed has often been exaggerated ; in the last respect he will not bear comparison with the thoroughbred or the American trotter. (J. A. S. W.) The American Saddle Horse.—The American saddle horse is a distinct and recognized breed of the horse industry, dating from the organization of the American Saddle Horse Breeders' associa tion at Louisville, Ky., in 1891. Antedating by many years, how ever, this organization of breeders, the five-gaited saddle horse was a necessary feature of farm life in the Blue Grass section of Kentucky and in many of the Central and Southern States. The early settlers who went over the mountains from Virginia into Kentucky, took with them at first horses without a developed gait, and of no particular breed. The Canadians had produced, by crossing on their mares of French descent stallions secured in New England and New York, a horse with a pace, or ambling gait, comfortable under saddle, and developed many years later into great speed in harness. A number of these Canadian mares and stallions were taken to Kentucky, and notably two, Copperbottom and Tom Hal, earned a large part in the saddle horse history of America. By the union of this Canadian blood with that of the native stock, and that of the thoroughbred and part thoroughbred which the Kentuckians were taking from Virginia, was produced the riding horse known universally in America, previous to 1891, as the Kentucky saddle horse. The five gaits which characterized the breed, and distinguished these horses from others were the flat-footed walk, the running walk (now often displaced by what is known as a "stepping," or slow pace), the trot, the canter and the rack.

Although the gaits of these earlier saddlers have been but little improved, their conformation has been radically changed. This has come about by the use of certain lines of thoroughbred blood, which modified and refined the physical appearance of these gaited horses. This thoroughbred part of the foundation is based on a "four mile" race-horse named Denmark, a son of Imported Hedgeford, an English bred horse taken to the United States in the early part of the 19th century. In later years another line of mixed trotting and thoroughbred blood, coming through Harrison Chief, has earned distinction in producing famous winners at the fashionable shows. That the saddle horse in America owes a large part of his ancestry to the racing thoroughbred is evidenced by an analysis of the pedigrees in the nine volumes of the American Saddle Horse Register, indicating that of the 27,00o pedigrees therein more than 90% contain thoroughbred blood.

At their best the American saddle horses are seen at the great exhibitions at Louisville, New Madison Sq. Garden (New York), Chicago, Kansas City, Los Angeles and other cities. Their average height is about 15 hands 2 in. and weight, 1,050 pounds. The neck is long, and gracefully arched. He differs, too, from the racing thoroughbred in being higher at the withers than over the hips, thereby relieving the rider of a feeling of pitching forward or "riding down-hill." The tail is curved and carried high above a line from the shoulders back. Among other famous saddle horses of the world are the Barb and the Turk and those of the Cossacks and Kalmucks. (C. M. T.) Ponies.—The native ponies of Britain are mostly bred in mountain and moorland areas; they are, except in the case of one or two breeds, dwindling in numbers. The replacement of ponies by electric systems of haulage in mines is the chief cause of the lessened demand for these animals. The chief breeds are the Shet land, the Highland pony, the Dales and Fell breeds of the North of England, the Welsh, the Dartmoor, the Exmoor, and the New Forest. The Shetland is well known as the smallest of these, with an upper limit of size, for Stud Book and show purposes, of 1 of hands. Many mature ponies are under 9 hands in height. Shet lands are sturdy and sure-footed little animals and make excellent first mounts for young children. The Highland pony is of two types. The larger form, found on the mainland, is rather of the cart horse type and is a useful animal for farm work. He is also often used for carrying game during the shooting and stalking seasons. The lighter type is found mainly in the Hebrides and is used by the crofter as a pack horse, carrying a pair of creels. The Fell and Dales ponies are of very sturdy and rather heavy build, whereas the southern breeds are of saddle type, and when crossed with small Thoroughbred or Arab sires produce excellent riding ponies. In Wales there are three types, a small (I 1 or 12 hand) mountain pony, a rather larger lowland breed with some Hackney blood, and a still larger form showing both Thoroughbred and Hackney influence, and known as the Welsh cob. The Hackney pony is closely related to the Hackney and is, except in the matter of size, of very similar type. The dividing line between the two is drawn at 14 hands. Hackney pony sires were formerly much used for crossing with Welsh and other native mares to produce driving ponies. The Polo pony stands in the same sort of rela tionship to the Thoroughbred as does the Hunter, some ponies being "clean bred" while others are the progeny of selected small Thoroughbred sires and mares of various sorts, from pure native to those with a high proportion of Arab or Thoroughbred blood. Playing ponies need to be of great strength for their size, and the best type is well described as a weight-carrying hunter in minia ture. Quickness and cleverness in turning and a high measure of intelligence are also essential. Ponies are trained to answer to the pressure of the reins on the neck, so that they may be perfectly controlled with one hand.

Horses are broken to ordinary work at two or three years old, but the rather elaborate training of a lady's hunter or a polo pony is rarely completed before the age of five or six. Length of life varies a good deal, but may be put, on the average, at a little over 20 years. Individual animals have been known to live beyond the age of 4o. In the care of horses the four most important points are careful regulation of the diet, provision for an adequate amount of exercise, thorough grooming and regular shoeing by a skilled shoeing-smith. In Britain oats is the standard food-corn, but elsewhere barley, maize, gram and other cereals and pulses are used. The daily ration varies according to the size of the animal and the nature and severity of his work. A heavy dray horse in regular and severe work may require 2olb. of corn per day, a medium-weight hunter Io or 12 and a Shetland pony about 61b. The ration of hay is, on the average, about the same by weight as that of oats, less for animals on fast work and more for those on slow. Many horses are put to grass during summer, and al though the change of diet is beneficial, a grass-fed animal is rarely fit for hard or fast work. An occasional feed of moistened bran and a daily swede or a few carrots are beneficial during winter. Horses must be fed at least three times daily. It is usual to chaff part of the hay and mix this with the corn, the remainder of the fodder being given in long condition. Horses should be allowed to drink freely before each meal. The amount of exercise required varies according to the condition that it is desired to maintain. A heavy draught animal will usually keep healthy on an hour's walk two or three times a week, whereas riding horses, if they are to be kept really fit, should have two hours of walk and trot exercise daily. Thorough and vigorous grooming is most important, espe cially if the horse is required for fast work; it not only keeps the pores of the skin open, but improves the tone of the muscles. Horses should be re-shod at intervals of four or five weeks, whether the shoes are worn or not, as the hoofs otherwise become overgrown. - Even when a horse is unshod the feet require to be trimmed and dressed occasionally. Stables should be kept cool and freely ventilated, clipped horses being rugged up in cold weather.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.--J.

Wortley Axe, The Horse; its Treatmentin Bibliography.--J. Wortley Axe, The Horse; its Treatmentin Health and Disease (1906) ; R. Lyddekker, The Horse and its Relatives (1972) ; R. Wallace, Farm Live Stock of Great Britain (Edinburgh, 1923) ; Schwarznecker, Lehrbuch der Pferdezucht (Berlin, 1926).(J. A. S. W.)