Horsemanship and Riding

HORSEMANSHIP AND RIDING, the art of managing the horse from his back; controlling his paces and the direction and speed of his movements. In the 16th century Pignatelli at Naples founded his famous academy of horsemanship, and the Italian school was so generally recognized that Henry VIII. and other monarchs had Italian masters of the horse. The Continental haute ecole developed from the teachings of these early masters. The duke of Newcastle's Methode nouvelle de dresser les chevaux (1648) was the standard work of the day, and in 1761 the earl of Pembroke published his Manual of Cavalry Horsemanship. The Austrians at the imperial stables at Vienna and later the French at Saumur continued the haute ecole system up to recent years.

It, however, never really found favour in England. In a modified degree it is seen to-day at shows and at the Olympic games, as an example of extreme obedience and control of the horse. Though haute ecole produced handiness and dexterity, the horse lost the activity required by the English. The horse's head maintained a fixed profile with a lofty head-carriage, overbent at the poll and balance permanently back, thus becoming cramped in its action and losing its powers of extension and speed. The necessity of handiness, but not at the expense of speed, was recognized by horsemen in Great Britain. Consequently certain "aids" were adopted from the haute ecole to obtain this desideratum. These "aids" exist in the British Manual of Cavalry Training, vol. i.

As opposed to the haute ecole the modern conception of a horse's balance is as follows. "A horse is said to be balanced when his own weight (and that of his rider) is distributed over each leg in such proportion as to allow him to use his powers with the maxi mum ease and efficiency at all paces." The head and neck form the governing factors in weight distribution, and it is by their position that the horse carries his weight forward or backward as his paces are extended or lected. Modern horsemanship cludes : (a) learning to ride. (b) Making an animal handy as a hack or charger or for polo. (c) Schooling over fences. (d) Show jumping. (e) Riding to hounds. (f) Racing over fences or on the flat.

Riding for Beginners.— From Norman times through the Tudor, Stuart and Georgian reigns up to the early part of last century, riding was considered an essential part of a gentleman's education. The introduction of railways and later of motor cars has resulted in the retention of the riding horse merely for pleas ure and sport. In spite of this there has been a large increase during recent years in the number of riders. All riding classes in horse shows are largely filled, including those for children, and in the hunting field the numbers have in no way diminished.

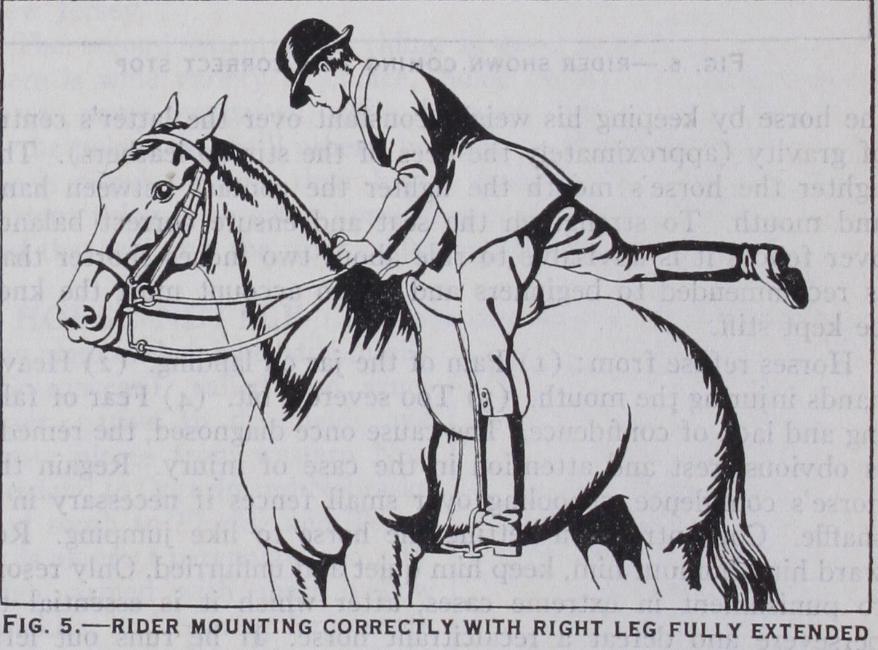

When mounting the rider should take up the reins in his left hand, at the same time holding a lock of the mane or the horse's neck above the withers with the same hand. Standing by the horse's near (left) shoulder facing the tail, he should hold the stirrup with the right hand for the reception of the left foot. Then place the right hand on the back arch of the saddle, spring off the right toe and drop lightly into the saddle.

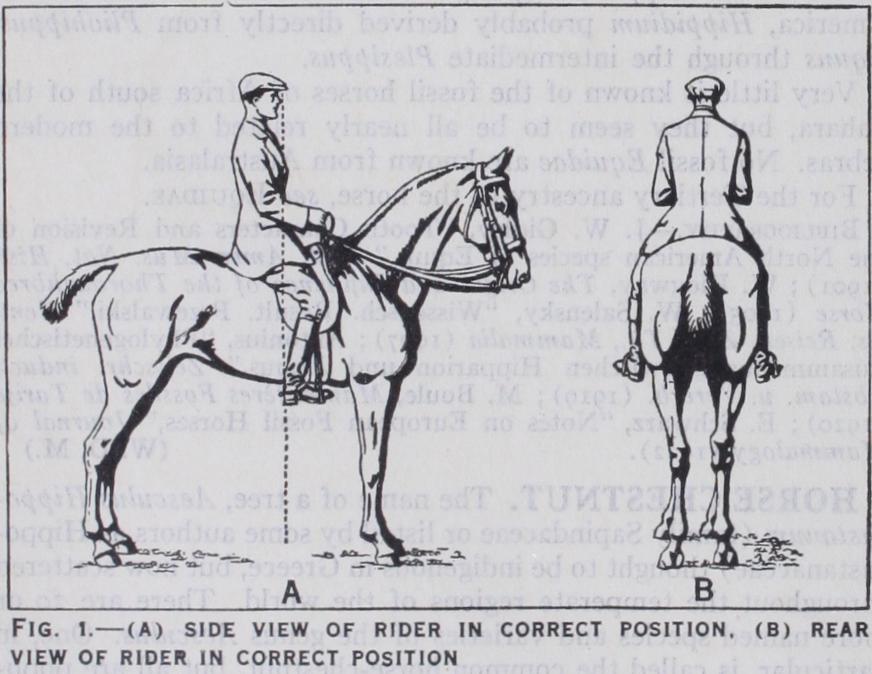

The rider's seat depends upon balance and grip. It is essential for the beginner to get a good natural seat, comfortable and strong without being stiff. After gaining confidence, first at the walk, then at the trot and canter with the aid of the stirrups, the rider should dispense with the latter for short periods and develop both his balance and grip.

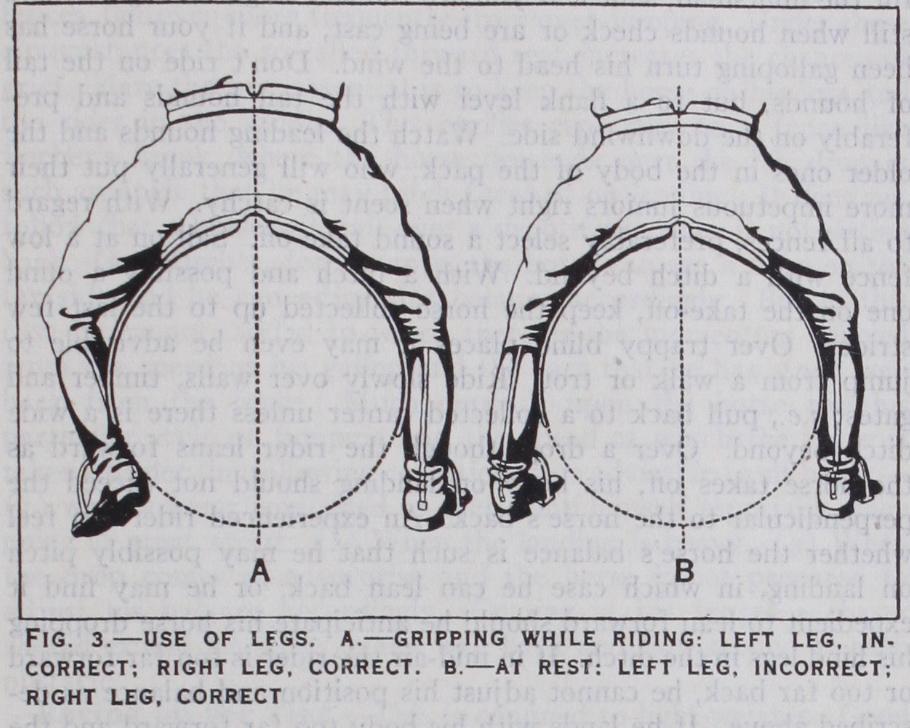

First of all, sit square to the front with the muscles relaxed, then grip with the flat of the thigh and the knee, the lower part of the leg parallel to the girth and the toes turned up. If the stirrups are now adjusted to support the foot in this position they will be at the required length. The body must be supple from the hips, swinging easily backwards and forwards as required or lean ing over in the direction that the horse is turning.

Ride as far as possible with a long rein; a strong and well bal anced seat independent of the reins is essential for good hands. The upper arm should be normally parallel to the body. The reins when held in both hands should be round the third or little finger. In the case of double reins the bit (curb) reins should be outside round the little finger, unless it is intended to ride more on the bridoon, in which case the position is reversed. The back of the hands should be towards the horse's mouth, and the wrists very slightly rounded. If the reins are held in one hand they are di vided on one side by the little finger and on the other side by the forefinger. By turning the wrist towards the body the reins are shortened. A springy tension is obtained between the rider's hand and the bit, by (I) the fingers; (2) the flexion of the wrist; (3 ) the movement of the forearm from the elbow.

The beginner will find difficulty in retaining his stirrups, but must avoid the habit of lowering the toes. He must learn to press on the stirrup, the heel forced lower down than the toe, which should be at a natural angle as when walking. Pressure should be firmer on the inside of the stirrup next to the horse so that the soles of the feet are turned slightly outwards. In this position, in creased pressure on the stirrup strengthens the grip and the rider will not lose his stirrups.

At the trot rise with the action of the horse, leaning slightly forward; at the canter sit upright, keeping the loins supple, suf ficient grip with the knee and thigh, and the leg below the knee vertical: at the gallop, shorten the reins, stand up in the stirrups, lean slightly forward and increase the grip with the knees. At all times keep as light a contact with the horse's mouth as is com patible with adequate control.

Handiness.

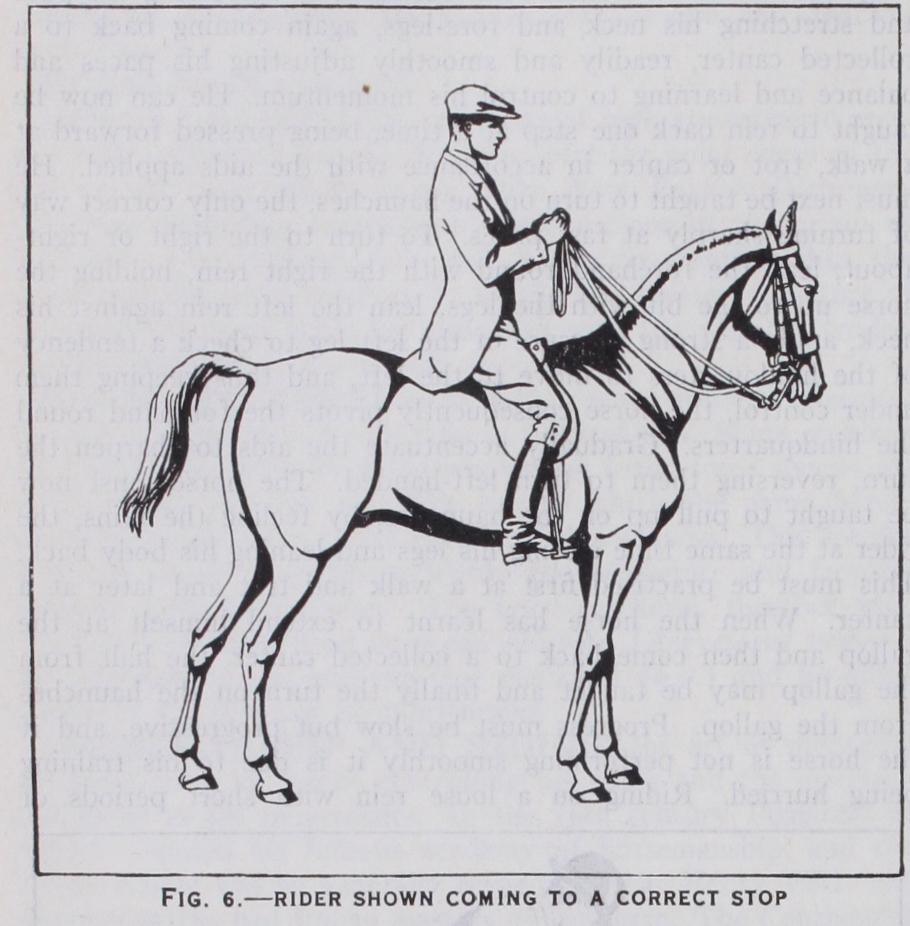

Handiness is the result of perfect balance in a horse whose movements are readily controlled by the rider. First obtain direct impulsion and free forward movement. To make a horse walk out, close the legs to his flanks and lightly feel the snaffle in his mouth. Occasionally teach him to diverge from the straight line by leaning the rein against his neck on the oppo site side to the change of direction. Preferably work on undulat ing ground. Increased impulsion from leg pressure in conjunction with the voice and possibly the whip will induce the horse to trot. When free forward movement at these paces has been obtained, the horse can gradually be taught to move collectively by a change of balance. The head is raised by means of the snaffle, a pressure of the rider's legs keeping the hind limbs well under the horse to support the weight thus brought back. Later he must be taught to bend from the poll and relax his jaw by a springy feeling of the fingers on the curb bit rein, the head being kept raised by the bridoon. The reins control the horse's forehand and the rider's legs the hindquarters; the combination of both controls the whole mass. The next stage is lateral impulsion, when the horse is taught to move diagonally forward (half passage) to one hand. To move to the half-right, apply a strong pressure of the left leg, pressing the left rein against the horse's neck, the right rein bend ing and leading him in the re quired direction, the right leg ap plied as required to hold the horse up to his bit. He must be kept col lected and the head bent in the direction he is moving. Reverse the aids to move diagonally to the left. To obtain lateral move ment to either flank, accentuate the above aids. These lessons should be taught first at a walk, then at a collected trot and later at a canter. The next lesson is the canter, which is a collected pace. For example, to canter with the off-fore leading, there are two methods. Firstly, trot collectedly on a large right-handed circle, increase the tension of the reins and the pressure of both legs, the left leg the stronger, at the same time bend the horse's head slightly to the left. He will then canter with the off-fore leading. Later, or if the horse is inclined to disobey this aid, make him half passage to the right at the trot, accentuate the aids to increase impulsion, when he will break into a canter with the off fore leading, then move forward on a straight line. Reverse the aids to canter with the near-fore leading. To change the leading leg at the canter check to a trot, half passage in the required di rection as above and break into a canter. By degrees reduce the number of paces at the half passage until the horse changes direct at the canter from one leading leg to the other. He must now be taught to canter on a loose rein, occasionally increasing the pace and stretching his neck and fore-legs, again coming back to a collected canter, readily and smoothly adjusting his paces and balance and learning to control his momentum. He can now be taught to rein back one step at a time, being pressed forward at a walk, trot or canter in accordance with the aids applied. He must next be taught to turn on the haunches, the only correct way of turning sharply at fast paces. To turn to the right or right about, lead the forehand round with the right rein, holding the horse up to the bit with the legs, lean the left rein against his neck, apply a strong pressure of the left leg to check a tendency of the hindquarters to move to the left, and thus keeping them under control, the horse consequently pivots the forehand round the hindquarters. Gradually accentuate the aids to sharpen the turn, reversing them to turn left-handed. The horse must now be taught to pull up on the haunches, by feeling the reins, the rider at the same time closing his legs and leaning his body back. This must be practised first at a walk and trot and later at a canter. When the horse has learnt to extend himself at the gallop and then come back to a collected canter, the halt from the gallop may be taught and finally the turn on the haunches from the gallop. Progress must be slow but progressive, and if the horse is not performing smoothly it is due to his training being hurried. Riding on a loose rein with short periods of collected work will teach him to relax his jaw to the curb bit. But the above syllabus must be executed first on a snaffle, then in a curb bit, again commencing at the first stage. The entire training may extend from six to eighteen months according to the temperament, condition and previous training of the horse. Patience and sympathetic handling are essential.

Schooling over Fences.—First lessons may be confined to jumping free in a lane, using a trained horse as a leader, or the youngster may be led in hand over small obstacles. Training must be progressive over small but solid fences and ditches. Later, when mounted, the rider should approach the fence at a collected canter with the reins in both hands. Three lengths from the fence lower the hands, still maintaining contact with the horse's mouth. Unless the horse is a naturally free jumper, close the legs to retain impulsion and to keep the horse's hocks under him. The rider should be sitting upright ready to lean for ward as the horse takes off, his own weight being borne on the knees, thighs and stirrups, the leg below the knee being free to drive on the horse. As the latter raises his forehand, the rider inclines his body forward, his weight being approximately over the horse's centre of gravity. He must be prepared in mid-air to give the horse more rein which the latter will require on landing. If the rider is leaning back at this period, he will upset the horse's balance and when jumping slowly he is liable to give the horse a chuck in the mouth as he is thrown back himself. This is known as the horse "jumping away" from his rider as opposed to the rider "going with" his horse. Schooling a youngster over simple fences the rider need not attempt to lean back. He can best assist the horse by keeping his weight constant over the latter's centre of gravity (approximately the dees of the stirrup leathers). The lighter the horse's mouth the lighter the contact between hand and mouth. To strengthen the seat and ensure correct balance over fences it is advisable to ride about two inches shorter than is recommended to beginners and on no account must the knee be kept stiff.

Horses refuse from: (I) Pain of the jar on landing. (2) Heavy hands injuring the mouth. (3) Too severe a bit. (4) Fear of fall ing and lack of confidence. The cause once diagnosed, the remedy is obvious, rest and attention in the case of injury. Regain the horse's confidence, schooling over small fences if necessary in a snaffle. Concentrate on getting the horse to like jumping. Re ward him, humour him, keep him quiet and unflurried. Only resort to punishment in extreme cases, after which it is essential to persevere and defeat a recalcitrant horse. If he runs out lef t handed turn him sharply to the right and vice versa. If he takes off too close to his fences make use of a ditch or guard rail nine inches high and two to three feet from the fence. Normally he should take off not nearer than the height of the fence and not more than eight feet from it.

Show Jumping.—Practically the same procedure should be adopted, but the rider should exaggerate the leaning forward, thus minimising the risk of touching the fence with the hind legs. The horse must lower his head to give free play to his loins when jumping, the more easily to tuck up his hind legs. It further assists him to judge his take-off and adjust his stride. Never steady a horse too late so that he cannot lower his head. The exaggerated forward seat is permissible as normally there is no question of jumping at speed over a drop on to sticky land ing, hence there is no risk of the rider being thrown forward of the horse's centre of gravity and both coming to grief. A good horseman on a well balanced handy horse can lengthen or shorten his mount's stride as required to take off correctly. This necessi tates a high standard of training and horsemanship. Show jump ers improve with years and experience. Horses like Broncho and Combined Training, who jumped for England and won the King George's Cup and the Championship at Olympia, were probably at their best when over twenty years old.

Riding to Hounds.—The seat is the same as for schooling over fences. Good horsemanship is essential for riding a young horse in a hunt. Never jump unnecessary fences, as it is unfair on the farmers and tiring to the horse. Hold your horse together over heavy ground, picking out the best going. Hold a gate open for the huntsman, shut it if you are the last to go through. Stand still when hounds check or are being cast, and if your horse has been galloping turn his head to the wind. Don't ride on the tail of hounds, but to a flank level with the tail hounds and pre ferably on the downwind side. Watch the leading hounds and the older ones in the body of the pack, who will generally put their more impetuous juniors right when scent is catchy. With regard to all fences, preferably select a sound take-off. Sail on at a low fence with a ditch beyond. With a ditch and possibly a .olind one on the take-off, keep the horse collected up to the last few strides. Over blind places it may even be advisable to jump from a walk or trot. Ride slowly over walls, timber and gates; i.e., pull back to a collected canter unless there is a wide ditch beyond. Over a drop, though the rider leans forward as the horse takes off, his body on landing should not exceed the perpendicular to the horse's back. An experienced rider can feel whether the horse's balance is such that he may possibly pitch on landing, in which case he can lean back, or he may find it expedient to lean forward should he anticipate his horse dropping his hind legs in the ditch. If in mid-air the rider is too far forward or too far back, he cannot adjust his position and balance as de scribed above. If he lands with his body too far forward and the horse overjumps and pecks badly, the rider's weight is thrown forward of the horse's centre of gravity and both will come to grief. The horse must have freedom of his head to stretch his fore-legs over a wide place or to save himself if he has blundered on landing. Certainly the rider cannot keep him on his legs by holding him up with the reins. A horse that stumbles can be held together to prevent this, but when he has actually stumbled badly, freedom of his head admits a reasonable chance of re covery. Banks are encountered in many countries. They may have a ditch on one or both sides and may be crowned with a hedge. Invariably they should be ridden at slowly to prevent the horse attempting to fly them, and at the same time giving him time to change his legs at the top. He requires a free head to alternate his change of balance when negotiating banks. A line of pollards indicates the presence of a brook. If the hounds at tempt to jump it, it is safe to as sume that the horse can clear it.

The rider must be determined or he will fail to inspire his horse for the effort. Pull the horse to gether about twenty lengths from the brook, preparing him to ad just his stride for the take-off, then send him on with increased pace the last few strides, hold ing him straight at the obstacle.

Impetus must be maintained, and this will ensure clearing a good fifteen feet of water. Over dykes and big bottoms it may be necessary to crawl down one side, pop over the bottom and clamber up the far side. Obedience to the rider's leg is necessary for opening gates. Once unlatched, the horse can be trained to push open the gate, the rider giving the final push with the hook of his whip. When pulling back a gate with the latch on the left use the whip in the right hand, and vice versa.

Racing over Fences.

Over hurdles the jockey keeps his weight constant over the horse's centre of gravity; viz., he adopts the modern seat of the flat race jockey, the weight being well forward over the pivot of the leading foreleg. This position gives the maximum assistance to the horse. In steeplechasing over park courses, the same principles are adhered to, but to a lesser degree, as the rider must be prepared to lean back if a horse blunders. The impetus of a bold fencer to some extent counter balances the leaning back of the rider's body, but to enable the horse to get away from his fence with the utmost speed after landing, the rider must be forward in the recognized position for galloping. Over Liverpool, horses often fall from hitting the fences, but even more frequently from over-jumping. Under these circumstances the so-called forward seat increases the chances of grief. Here the first essential is to keep the horse on his legs and the rider in the saddle. This applies especially to a fence like Becher's brook, where the horse descends over the big drop at such an angle that he may pitch forward on landing. It does not follow that a horse will fall over a drop if the rider is not sitting back. Over timber, for instance, the horse can see a drop on the far side and he can adjust his balance accordingly. But in this case he cannot, added to which there is the momentum derived from the speed of his gallop and the fact that he has stood well back from the fence. Much depends upon the horse and his particular style of jumping and the speed at which the fence is taken. Under the following conditions it is advisable to sit back:— (1) when a horse is inclined to over-jump himself especially when going at great speed. (2) When the landing is heavy. (3) When the drop comes as a surprise and the horse is not prepared to adjust his balance accordingly. Coming at his fences a chaser should extend his paces, stand well back and gain ground at each obstacle.

Racing on the Flat.

This is confined to light-weights. Good jockeyship entails early apprenticeship to get the necessary experience. At first a lad should ride on easy horses, attention being paid to the length of his stirrups and reins. The American jockey, rod Sloan, was the first exponent of the modern racing seat in Great Britain. The advantages are as follows: (1) Wind resistance is reduced to a minimum. (2) The racehorse must advance his centre of gravity with the free extension of his head and neck to get full extension of his fore-limbs. Therefore the rider's weight must be proportionately advanced. (3) The lead ing foreleg at the gallop exerts the greatest effort, consequently a tired horse keeps changing his legs; the rider's weight being over the pivot of the leading foreleg reduces this effort. (4) At the same time the rider relieves the horse's loins of as much weight as he can to enable it to bring its hind legs as far forward as possible. By adopting this method he obtains the maximum of propulsion.The lad first learns to sit still and obey orders. He next learns to keep his place on different types of horses, driving a sluggard, soothing and restraining an impetuous youngster, remaining quiet on a free but temperate horse. During this home training he de velops a judgment of pace and learns to appreciate the peculiar ities of different horses. If he is to become a successful jockey he must have brains, be keen, determined and in sympathy with horses. The latter quality is essential for good hands which alone can deal with a wayward animal. With these qualities he will develop confidence, and once endowed with this asset he is well on the road to success : smartly off at the start, with his horse instantly balanced in its gallop, seizing the opportunity of coming through his field, getting on the inside at the turns, keeping still when well placed and holding his horse together to make his final effort with a strong finish when required.

See Baucher, Passe-temps Equestres (1840) ; Hundersdorf, Equita tion allemande (1843) ; d'Aure, Traite d'equitation (1847) ; Raabe, Methode de haute ecole d'equitation (1863) ; Methode d'equitation (1867) ; Barroil, Art equestre; Fillis, Principles de dressage; Hayes, Riding on the Flat, etc. (1882) ; Goldsmidt, Bridlewise (1926) ; Brooke, Horse-sense and Horsemanship (5926) ; H. R. Hershberger, A Work on Horsemanship (1844) ; Henry William Herbert, Horse and Horsemanship of the United States and of the British Provinces of North America (1857) and Hints to Horsekeepers; A Complete Manual for Horsemen (1859) ; T. C. Patteson, Observations on Riding (190 1 ) and Saumur Notes (1909) ; H. L. de Bussigny, Equitation (1922) ; Baretto de Souza, Elementary Equitation (192 2) ; L. L. Fleitmann, Comments on Hacks and Hunters (1922) ; I. Maddison, Riding Astride for Girls (5923). (G. BR.) Riding, once the medium of transportation of men from place to place, has become in the 2oth century in the United States solely a medium of recreation. As such it is increasing rapidly, there being from 30o to S00% more riders in and near cities in 1928 than there were in 1921. The first essential for riding is adequate facilities—that is, good bridle paths in city parks; riding trails near cities; and in suburban districts, where wealthy men have large estates, arrangements whereby riders from one estate may use trails on neighbouring estates. For such purpose swing ing gates or panels are installed to permit easy passage of riders. This adds variety to the route—which is important, for when men and women must ride over the same path every day they sometimes grow tired of the sameness of scenery and terrain.

Chicago outranks other cities, except London, in excellency of bridle paths, its paths being broader, better constructed and better maintained than any others. Boston and New York have good paths through the public parks, and Washington's paths are good though somewhat narrow. One of the most beautiful stretches of bridle path anywhere extends through the Wissahickon natural park area in Philadelphia. Automobiles are forbidden in this area, which is an added attraction, for where riders are forced out upon paved highways in close proximity to speeding motor cars there is great danger of accident. St. Louis, San Francisco, Los Angeles and other cities also have built good paths and are steadily improving them. There is likewise amazing development throughout the country in riding trails—which are distinguished from bridle paths through the fact that they are natural trails lead ing over rights-of-way. Outstanding among these are trails on pri vate estates about Piping Rock, L.I., Greenwich, Conn., Aiken, S.C., Oconomowoc, Wis. and public trails in forest preserves of Westchester county, New York, and Union and Essex counties, New Jersey.

The second essential to riding is good mounts, and in these there is wide variety of choice. Some prefer three-gaited saddle horses, some five-gaited, while those who play polo want mounts of the polo type. Still others, brought up in sections where hunt ing is popular, select their horses from hunter stock. The im portant thing is to get a horse that is sure-footed, light-mouthed and that will give the rider a pleasurable and safe ride.

(W. Di.) (Solanum carolinense), a North Ameri can plant of the nightshade family (Solanaceae), called also sand brier, native to dry fields and waste places from western New England to Ontario and Nebraska and south to Florida and Texas.

It is an erect perennial, 1 to 4 ft.

high, armed with sharp yellow prickles, and bearing large more or less deeply-lobed leaves, light blue or white flowers, strongly re sembling those of the potato, and orange-yellow berries, about in. in diameter. In sandy or gravelly soils the horse-nettle sometimes becomes a troublesome weed, spreading not only by its seeds, but also by its long under ground rootstocks. (See SoL