Hosiery

HOSIERY. This familiar term originally referred to articles worked in the knitted stitch used for footwear and underwear, but it has come gradually to embrace a much larger range of knitted products than those specified. The knitted stitch has greatly extended its field of usefulness and through all those developments hosiery has stood as the main generic term which covers all classes. The hosiery trade includes generally the production of all classes of articles worked in the knitted stitch. Knitted fabric is used to an increasing extent for intermediate and outer garments and there is an increasing tendency to subdivide hosiery into footwear to denote stockings and socks, underwear for articles worn next to the skin ; intermediate knitted wear is applied to articles worn under the outer garment but not next the skin, outerwear is used to indicate articles such as coats and costumes. In America the term hosiery has been retained as referring to articles of knitted footwear only, the other classes just mentioned being often known as knitwear.

Plain Knitted Fabrics.— There is probably no class of tex tile which has undergone greater recent development in its scope and uses, and the knitted texture is supplying an ever-increasing proportion of our textile requirements.

Basically, knitted fabrics fall into two groups : weft and warp fabrics. These are again divided into the classes of plain stitch and rib or ribbed stitch. A third group, one which is not so widely used as the first two, is the tuck stitch, which can be better consid ered as a modification of plain stitch, being a repetition of needle loops forming half stitches to the front and to the back of the fabric. The plain knitted fabric is constructed from a single thread which runs crosswise and is intersected into a series of loops which hang upon each other in sequence. Fig. I gives a diagram matic view of the right side of a plain knitted fabric employed for the vast majority of hosiery articles and the stitch in black shows one convolution of a loop of which all the other loops are simply repeats. In following this crosswise, we have what is termed a course of loops, hence this type of knitted fabric is termed a weft texture as it is formed by looping a thread which runs horizontally in the fabric, similar to the weft of a woven fabric. But it has another dimension, which is the loop regarded in the width, a wale representing an upward plus a downward curve of the stitch. These wales are measured in the width and each wale is formed on one needle, so that in the machine the needles per inch give the wales per inch. For a well-balanced knitted fabric the courses per inch should in general exceed the needles or wales per inch by 40% to 5o`0. An examination of fig. I will show that the looped structure has a characteristic elasticity in the width, as a pull in this direction has the effect of straighten ing out the courses and the knitted fabric can in some varieties of stitch be increased from 75% to 8o% in width by stretching. This extreme stretch is found particularly in the rib stitch fabrics. In the length the normal stretch seldom exceeds a 25% increase, but there is much greater tensile strength in the direction of the length than in that of the width. In the width the strain comes on to the individual threads in the course, whilst in the length the succeeding layers of loops support each other. Knitted fabric sold in lengths for cutting into garments is often termed stockinette or tubing; if it is of especially firm or dense structure, it is loosely described as a "cloth." Texture.—In hosiery there are three types of texture : (a) A lean variety which is gauzy in appearance and lacks consistency and stability due to the fact that the yarn is too thin for the gauge or allotted space, and the available space is too open for the thick ness of the yarn employed. Fig. I illustrates a fabric which would come into this category. (b) Fabrics which are correct for the gauge have the spaces between the needles adequately filled with yarn, but the spacing still allows for the natural elasticity of the fabric to operate. Fig. 2 shows a fabric worked in the same sett or gauge of needles as fig. I but with the yarn much thicker to fill out the interspaces of the loops.

(c) A full fabric is one where the yarn is too thick for the available loop space, so that the texture is stiff and stodgy in nature. Such a fabric although thicker and heavier in weight will give less satisfactory service in wear as it lacks resilience, and when strain is applied the stitches soon wear each other out and holes appear.

This interdependence of loops is at once a great advantage and a considerable drawback. It is a benefit to have elasticity for such articles as underwear when the stretch adds to the comfort as the garment yields to the movements of the limbs. It is a disad vantage to have those loops so intimately dependent on each other, because when a thread breaks the loops connected with it give way all round and a large opening is created. This accentuates what is known as the laddering tendency, for if a stitch gets broken strain will cause this loop to unravel and run right down the fabric. The elasticity of the knitted fabric is a great asset in sports' wear, when free action of the limbs is required ; it has also another ad vantage in that articles can be made in a smaller range of sizes, for the material within certain limits stretches to fit an ample figure and contracts to drape a more slender form. In the more rigid woven cloth the garments have to be much more accurately cut to fit each wearer. The fact that large numbers of wearers can be accommodated with the same size of garment accounts for the readiness with which those articles are taken up by the public; they can secure the article on the spur of the moment, without the tedium of fitting-on.

The plain knitted fabric owes much of its versatility to the fact that it has a different appearance on the wrong side and on the right, for this is used in many ways to vary the stitch, increase its weight and give ornamental results. The characteristic of back or wrong-side fabric is that the stitches form a series of intersect ing semi-circles. Fig. 3 illustrates the well-known rib stitch so indispensable on knitted articles. The vertical rows of stitches marked 2, 3, 6 and 7 show two needles or wales with their stitches of right-side fabric. Alternating with those two wales are two (4 and 5), which have their stitches reversed to show the back or wrong side of the fabric. The whole setout in fig. 3 would be termed a 2-and-2 rib stitch, and machines can be arranged to give i-and-i, 2-and-I, 3-and-3 and so on rib stitches. The r-and-r or plain rib stitch is the best known as being largely used for the rib tops or bottoms of gar ments. This stitch has a greatly increased latent elasticity or stretch over the plain fabric, and it grips the limb more firmly so as to retain the sleeves and garment extremities in position. But the rib stitch gives articles of heavier weight and bulkier to handle, be cause a larger amount of material can be absorbed by this type of loop than the plain variety. Rib stitch imparts to the fabric an enormously increased elasticity in the direction of the width, and certain grades of hosiery base their appeal to the public to this feature. What is known as the "Swiss" vest for example is cut from continuous lengths worked in a slack rib stitch, which has such an enormous elasticity as to fit the body without shaping the parts. It is thus possible to produce the material in circular form at high speed of production at one uniform width. The plain rib is employed largely for cuffs or legs of men's underwear, while the 2-and-2 rib, as shown in fig. 3, is often used for the cuffs of knitted gloves. The famous Derby rib is usually a 6-and-3, that is 6 face stitches alternating with 3 back fabric stitches in the direction of the width. This style of rib is often used for stockings, ribbed hosiery being an important branch of the trade. Children's hosiery are often made in the rib stitch on account of the greater grip which is exerted, and also because rib knitting lays more yarn into the body of the fabric which makes for greater durability. It is also largely used in stout textures for men's socks. The rib stitch and its derivatives are also most useful for outer garments ; what is known as the half cardigan is a variation of the i-and-i rib stitch, where on one side two threads are drawn into the same loop thus decreasing the intersections and allowing a greater weight of yarn to be inserted. This is the stitch of the well-known cardigan jacket, and whenever it is required to increase the weight and bulk of a fabric over what is possible with the plain stitch, the cardigan principle is employed.

Purl Stitch.

Fig. 4 gives an illustration of what is known as the pearl or purl variety of stitch, where the same principle of right-side and wrong-side loops is adopted to produce the pat tern, but this occurs in the hori zontal direction. This is the 2 and-2 purl stitch where the up per and lower pairs A, B and E, F are set in wrong-side stitches and the centre pair C and D are face fabric loops. Now this change in direction produces quite a different appearance in the fabric to either the flat or the rib. The needles build needle loops on the front bed or on the back bed of the machines to form the design instead of shifting continuously from front to back as in knitting plain purl stitch. The manner in which purl stitches erect themselves on the face of the fabric accounts for the great effectiveness of designs wrought on this principle, for quite a small disturbance in the loop direction produces a striking result in the fabric, and very ornamental designs can be made by arranging these wrong-side stitches in some simple pat tern. Variation in the levelness of the texture naturally debars this type of fabric from being worn next to the skin, but for outer garments these raised effects yield embossed designs where the surface shows an effect in light and shade, the high portions being the needle loops forming the pattern with the plain fabric in the base. The interesting play of light on the surface of the knitted fabric accounts for its popularity in such mediums as artificial silk. The plain stitch on the face side resolves itself into a series of thread sections which hang towards the left alternating with a series which have a bias towards the right. This variation in direction gives an interesting and attrac tive sheen to the fabric, and in fine gauges creates twilled and satin-like effects with the delicate play of reflected light.

Fabric Grades.

Knitted fabrics are classified into two grades: (a) fabrics pro duced on machines using the bearded or spring needle, and (b) those knitted by means of the latch needle. A view of the bearded or spring needle is shown at fig. 5 and is seen to consist of a piece of wire flattened at the upper end and turned round to form a beard or spring; the stem and grooves into which the spring is pressed are shown. The term beard was given to the needle in the old handframe, but this is gradually giving place to the term spring in the modern power knitting frame. In the handframe days of the industry there was a pronounced tendency to give the parts of the machine names which corresponded to parts of the body. Can this be wondered at when one considers the ardu ous nature of the work on the handframe, when every limb was brought into use at each course of loops ; the machine in fact became part and parcel of the worker, hence there are such parts as the sinker nose, the belly of the sinker and its throat. The fashioning points were the ticklers, whilst the sinker had its tail. It is remarkable that with all the advances in modern knit ting practice as regards speed of production, the products of the spring needle machines are still held in the highest esteem as regards quality of texture and fineness of mesh. This needle can work thicker yarns relatively to the latched needle, and the tex ture is close and therefore, less liable to run and ladder. The term "spring" knit indicates goods made on spring needle ma chines. Until recently the making of spring needles was a typical European industry, while latch needle manufacture was an Amer ican invention and product. In 1928 large quantities of spring needles were made in America. The world's largest producer of full-fashioned hosiery knitting machines, located in America, makes its own spring needles.

The Spring Needle.

The system of making a course of loops by means of the spring needle may be learned from examination of figs. 6, 7 and 8 which represent successive stages in the process. The needle is there shown, on the lower stem is the fabric with the last-made loop hanging on the needle, the new thread is indicated, just passing under the spring or beard of the needle. To the left is shown a member usually known as the presser, which must always figure in any system of mak ing loops by means of the spring needle. In fig. 6 the needle has just received its new yarn, at fig. 7 the needle has descended and the new thread reaches the extremity of the needle inside the needle spring. The needle at this stage is being acted upon by the presser, which is pushed forward to force the spring into the groove carved out for it in the needle stem. In this position the needle slides still further downwards, so that in fig. 7 the old stitch is noticed to be sliding on to the needle spring and over it. This is called the landing of the stitch and is the crux of the whole knitting action, for in fig. 8 the needle has descended to its lowest extremity, drawing through the new thread, and discharging the former loop from the needle which now takes its place normally in the fabric.The two needle types spring and latch are shown in comparison in figs. 9 and to, where the spring needle is shown cast in its lead, and this is the usual form in which this needle is housed in the machine. Each frame has its mould according to the sett of the needles, which are laid ;n pairs in grooves of the mould ; molten lead is then poured into the shape shown above. This forms a con venient way of handling the needles in the machine, and it is by counting the number of such leads in a space of 3 in. which con stitutes the gauge in flat machines using the spring needle. Thus a 21 gauge frame would have 21 such leads, each with two needles needles on three inches =14 needles per inch. Spring needles are made with butts at the lower end to fit into the machine and are thus locked into place in the needle bar instead of being leaded. In working fabrics "to the gauge," therefore, this system enables one to say 24 gauge has 24 courses per inch, 18 gauge has 18 courses per inch, which corresponds to the general dictum regard ing texture that the courses per inch should number 50% more than the needles or wales per inch.

Latch Needle.

Examination of fig. t o will show the details of a standard type of latch needle, the various parts, viz., the latch, hook, stem and heel or butt being illustrated. The hook is used to take the thread from the guide, and the hook is closed and opened by the latch, which hinges on a rivet. The heel or butt, is that part of the needle to which the movement is im parted in the needle tricks of the machine, moving it up and down during the stitch formation. To form the stitch the old stitch rests on the lower stem of the needle, whilst the new yarn is taken by the needle hook. The needle is then drawn towards the right, which brings the latch against the old stitch to close the hook. The needle proceeds still further in the same direction, and the old loop slips off the needle end with the new thread drawn through the old one. Examination of the latch needle will show that there are many fine points to be mastered in its manufacture. The pro vision of the latch and its hollow or spoon to fit over the hook is a very delicate piece of engineering, whilst the poising of the latch on its rivet presents a number of problems in minute meas urement. The butt, with its curious bend, also presented many difficulties in tempering of the metal, owing to the proneness shown by the wire to break at the peak of the butt. In many types of needles this bending is now eliminated by constructing a different form of butt, whereby the wire is flattened out at that end to give a heel which can be acted upon in the required manner.Examination of the needles shown in fig. 9 and i o ex plains many of the defects which are to be found in hosiery goods. In the spring needle a delicate point is the spring, which after many pressings loses its potency and becomes flattened. This gives rise to defects known as "split" stitches, where half of the yarn goes over the spring and another half gets underneath during stitch formation. Machines are being built of 54 gauge with the spring needle, which means they have to be set with 36 needles to the inch. They have to stand at exact distances apart in the machine, or what are known as needle lines will appear and irregular stitches will be formed where one narrow loop is seen side by side with one which is correspondingly larger, the narrowness of the one con trasting markedly with the wideness of the other. The secret of success in producing level meshed goods from the spring needle is constant pliaring of the needles into perfect alinement in every direction, in which operation the mechanic develops a very fine sense of judging minute distances. Any mixing of needles so that finer or coarser gauge needles merge is reflected in the regularity of the fabric. Latch needles are subjected to expert examination by the manufacturer on the following points: (a) size of hook, (b) length of latch, (c) the needle backs are examined for sharp corners of the rivet which may project, (d) the height and breadth of the butt. Latches which project at the back cause what are known as "whiskered" wales, because the tiny latches act as small scissors to cut the filaments or fibres of the yarn as it passes over the needles. When these severed fibres occur on the same needle right down the material they constitute a serious defect, and stitches weakened in this way easily go into holes at early stages of wear.

On any particular gauge of wire there are several sizes of head which may be made according to the type of fabric which it is sought to produce. The needle manufacturers produce a standard size for their needles according to gauge, but particular manu facturers obtain needles with heads larger or smaller than the standard type. The larger head allows greater space in the fabric, whilst a smaller head allows the yarn to be packed more closely in the cloth to give a denser texture.

Rib Fabric.

In figs. I I to 14 the process of making rib fabric through the agency of the latch needle is illustrated, the needles representing the relative posi tions they would occupy in a ma chine such as a circular rib frame where the vertical needles are ar ranged round the circumference of a cylinder and the horizontal needles are set around the cir cumference of a dial, these two parts acting together during the knitting process. The fabric is so seen to be passing down the inside of the machine on the left, and in fig. t t the needles are in the act of moving into their respective positions to re ceive the new yarn to form a stitch. In so doing the old stitches open the latches, the horizontal needle moves to the right, the vertical, upwards.In fig. 12 the thread makes its appearance and is taken into the hook of the upright needle, which begins to slide downwards. At the same time the adjoining piece of yarn is laid over the stem and in the hook of the tal needle. In fig. 13 the two needles are in possession of the thread and the old stitches on both sets of needles have closed their respective needle latches. In fig. 14 the movement is plete; the horizontal needle has moved left to draw its new stitch through, the vertical having made a similar movement by dropping lower down. If the vertical needles are arranged two and two with the horizontal needles, then a fabric as illustrated in fig. 3 would be the result, the vertical needles giving the face-fabric stitches and the horizontal needles the back-fabric stitches.

Trade Divisions.

The hosiery trade is divided into sections such as the full fashioned, circular knit or seamless and the cut, according to the manner in which the articles are constructed and assembled. Similar divisions hold in the underwear and in the knitted outerwear industries. In the latter two, however, most goods are made of the cut type, and by comparison not much of the full-fashioned type. In the underwear trade most of these goods are made of the tubular knitted fabrics which are tailored to shape by cutting and sewing. The sweater and knitted outer wear industry employs similar methods in the fabrication of gar ments, excepting fabrics made on flat knitting machines which are also largely employed. In making full-fashioned goods fash ioning is done in the same way at the needles of the machine as in the hosiery industry, the difference being, however, that single unit or section machines which are more satisfactory are usually employed.In the full-fashioned trade the garments are made in flat pieces and afterwards joined together with a perfect selvedge, as the edge loops can be used to connect the seaming thread. With goods cut from tubular web the cut edge is raw and the stitching needle has to penetrate a little way from the edge to obtain a hold, which gives a rather rough seam, although great improve ment has been effected in this respect by the invention and wide spread adoption of flat seams. Here the cut edges abut on each other or slightly overlap and are annealed in a manner by close intersection of from five to nine threads with a seam of some neatness. The perfecting of this method of seaming has con tributed enormously to the greatly enhanced status which such cut-up goods now enjoy on the market. The fabric for this trade is produced on the latch or spring needle circular web ma chines, and in cutting out many plies of fabric can be dealt with at one and the same time on the lines of mass production for garments for wearers of moderate means. The great virtue of the full-fashioned article is that exact interpretation can be given to any size, dimension or physical abnormality and the fabric texture is identical all the way through the garment.

The seamless trade is also a most important one, particularly in the production of knitted footwear and gloves. By the modern seamless automatic machine a hose can be produced in a few minutes entirely seamless except for a small seam, which has to be made across the toe. In the case of stockings, the leg is shaped from calf to ankle by altering the size of the stitch; the top is worked in an open stitch to give greater width, whilst from the calf to the ankle the fabric is worked in degrees of increasing smallness of loop to give a constricted shape to the stocking. This method of shaping the article suits an average wearer of moderate dimensions, but it does not stretch to fit a more ample figure. In seamless hosiery the same number of needles are in the knitting of the leg proper as in the calf of the stocking In the full-fashioned stocking the decreased width is obtained by reducing the number of stitches in action, and the foot of the stocking is made at right angles to the leg which insures a better fit at that point. Variation in width is obtained by reducing the number of stitches in work so that the texture remains identical throughout.

Warp Loom Knitted Fabrics.

Warp loom fabrics may be regarded as taking an intermediate place between the knitted and the woven texture. They resemble the woven fabric in having a warp arranged in with parallel threads side by side on a beam or roller, but these threads are given a sidewise shogging motion so that the threads interloop with each other. A view of this type of texture is given in fig. 15, where the pattern is arranged one black, one white, and five threads are shown intersecting and marked i to 5, whilst the needles are given from A t o E. Crosswise the courses of loops are marked from i to 6 and tracing thread number I ; it will be noted that it makes a loop on needles A and B alternately, thread number 2 moves alternately from needle B to needle C and back again; thread number 3 moves from needle C to needle D and back again alternately, and so on throughout the entire fabric. This is the simplest form of warp loom stitch, termed the "Denbigh" lap, and these threads are accommodated in a single bar. The lap of the thread guide bars can be greatly diversified, and the lap in one direction may be extended to a large number, say 4o or 5o needle spaces, which gives the characteristic zigzag edge which is so attractive for the extremities of garments. The side-to-side lap of the threads also gives a unique intermingling of the colours of the warp. and, using black and white, one can obtain intermediate blends of grey by the manner in which the sidewise movement melanges the colours. Greater diversity of pattern is obtained by the use of two or more bars as each bar can be given a different kind of lap. The warp loom is con structed with spring and latch needles and what is known as the "Raschel" type is built with latch needles after the manner of a rib machine, in that there are two needle bars differently set so as to give contrary knock-over to the threads similar to a rib effect. The two bars do not act together, however, but rise to knit alternately. In this branch of the industry practically any type of fabric can be produced, as the two needle bars enable the texture to be greatly increased in bulk or density and in stiffness. By this means also double face fabrics can be made as for mantle fabrics, plain style on the face with fancy tartan patterns on the back. Men's suiting and overcoating fabrics as well as muffler and necktie fabrics have also been largely worked on this machine to the required density and firmness. The warp loom, by reason of its lap at an angle, is specially adapted for making diamond styles of patterns where the figure stands on its edge, and quite a simple form of design arrangement produces a maximum of effectiveness. Imitation lace styles, cellular fabrics and openwork designs can be made in this style of fabric, and by having the bars crossing in the direction of their motion, two stitches can be worked on the same needle which greatly reduces the laddering propensity of the fabric and practically makes it run-proof. In fact various types of two-bar work having this form of lap are definitely placed on the market under a guarantee that the fabric will not ladder, as the threads in the two bars are made to lock each other. The jacquard machine is readily adaptable to the use of the jacquard harness for controlling the individual yarn ends and is accordingly used extensively for making lace fabrics of several types and weights. The tricot type of warp knitting machine is used for the production of glove silk fabrics for the glove and silk underwear trades. This particular cloth is referred to as tricot and differs from Milanese in that it stretches in only one direction.Another interesting variety of the warp loom fabric is known as the elastic stitch, also referred to as "Swiss" muffler stitch, which is worked in cellular form and possesses a wonderful elas ticity, particularly in the length. This is a suitable fabric for such items as hat bands, and it is also used largely for scarves. The fabric is worked at full width, and afterwards divided by severing a thread which is drawn down leaving the fabric with a perfect selvedge at the scarf widths. Warp loom fabrics have limitless scope as regards colours, as each thread can be of a different colour if desired.

Milanese Texture.

One of the most famous warp loom fabrics is the Milanese texture, which is figuring more and more in textile requirements. It is made on the special loom of the same name, and there is no other textile fabric exactly like it. The Milanese machine has one warp, wound on large spools which are mounted in a carriage in the bottom of the machine and which travel around a flat elliptical track in unison with the transfer ence of their respective warp ends to the neighbouring needles in stitch progression of courses. There are two tiers of threads. one on the face and another on the back; the face threads lap needle by needle from left to right continuously from one side to the other, whilst the back threads similarly lap needle by needle at succeeding courses towards the left on the lower tier. Thus in a fabric with 4,00o threads it would require 4,000 courses for thread number one to travel to the 4,000th needle. At each course one thread reaches the last needle on the right, and is promptly transferred to the leftward-moving needles underneath; similarly one thread in the lower tier arrives at its last needle moving leftwards at each course, and is promoted from the lower to the upper tier to repeat its journey. At every course each needle holds two stitches, so that if one gets broken the remain ing thread holds the loop and prevents laddering. This is a great asset in such fabrics when made into garments and accounts for its increasing popularity. A further advantage is that the edge is more stable than the plain knitted fabric when cut, and a smaller seam can be made, as one does not require to take such a large bite from the fabric on either side. Thinner seaming threads can also be used which gives a small neat join very much prized in a cut undergarment. The fabric is made in gauges with about 3o face stitches per inch, which, counting the back, gives actually 6o stitches per inch, and Milanese lends itself to working in the popular artificial silk. This is also the texture adopted for the well-known fabric glove which is usually worked in fine counts of single cotton, and the already dense mixture is rendered more so by a shrinking process, which consists in steep ing the material in caustic soda so that it swells and fills out the loop interspaces, thus giving it, when finished, a fine dense skin like fabric referred to as cotton suede, ideal for gloves. A Milan ese fabric is usually heavier than a tricot fabric and, therefore, usually more expensive.

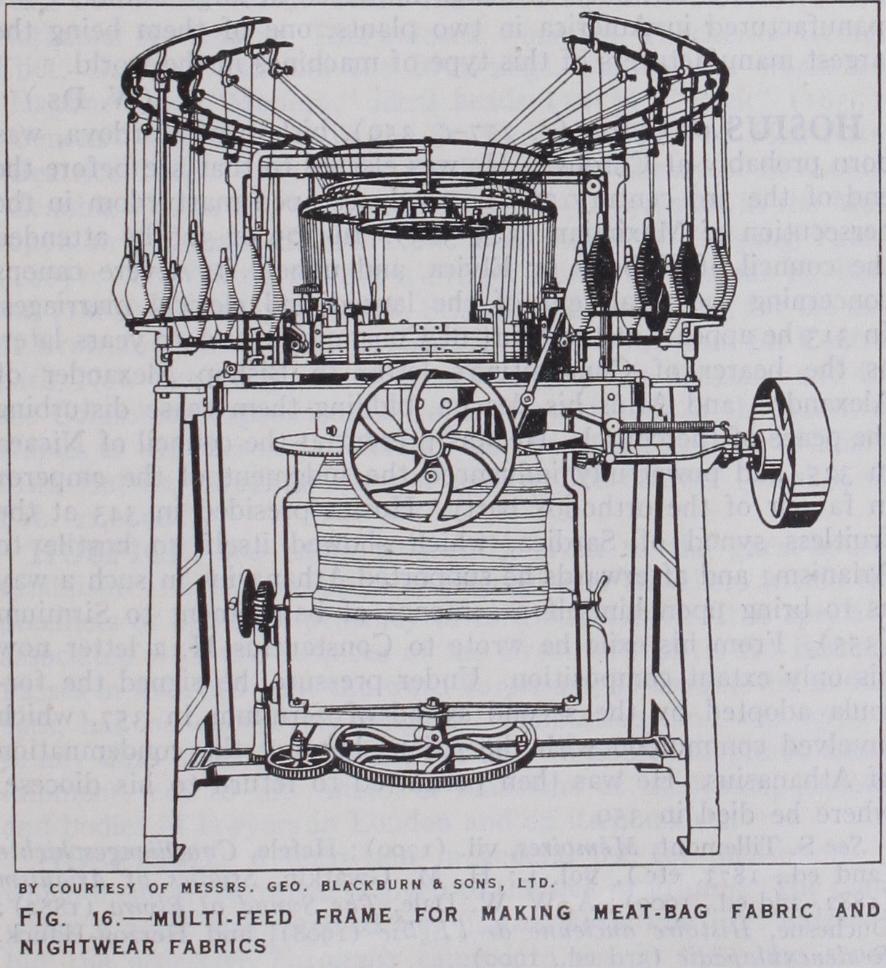

Multi-feed Machines.

Fig. 16 gives a view of what is known as the multi-feed frame, which is provided with latch needles and is set to give a colossal production of fabric, in fact the multi-feed knitting machine ranks as the fastest textile-producing machine in existence. It owes its high speed to the circular principle of construction, which provides for a large number of stitching-forming units being housed round the circle. They f ol low each other in close succession right round, so that in the large diameter machines 8o feeds are arranged, which means that for every revolution of the needle cylinder 8o courses of loops are inserted, and if there are to courses of such loops per inch, this gives 8 in. of fabric at each turn of the cylinder. If there are i o cylinder revolutions per minute, this gives 8o in. of fabric produced per minute, and allowing for stoppages this would yield about 2 yd. per minute. Naturally, with such a large number of stitch-producing setts round the circle the texture is not of the most regular description, but such gauzy fabric is useful for many purposes, notably for meat bags in which the carcases of animals are wrapped for transport, particularly in connection with the meat-packing trade. In lesser number of feeds than described above it is also a machine well adapted for the football jersey trade where bold cross stripes are required, and the threads are ar ranged in due colour order on the machine platform.

Fig. i7 gives a view of another circular machine, where the num ber of stitch-forming elements are greatly reduced to provide fabric of perfectly regular texture suitable for the outer garment trade. The usual number of feed ers for such machines runs from 8 to in the circle, and the adjust ments are specially designed to make each course of loop equal in length and tension. This machine is specially designed to provide for fancy coloured stripes and for the taking of several colour feed ers in the circle. It has played a vital part in developing the knit ted artificial silk fabrics. For stripes and pattern effects design wheels are added which are pro vided with bits to make selection of needles in the circle in accord ance with the pattern.

The Flat Knitting Machine.

Fig. 18 gives a view of the flat knitting machine, as it is termed, which in some ways is one of the most remarkable types of knitting mechanism. It was invented by the Rev. J. W. Lamb in 1863 and is also known as the Lamb knitter. The machine shown in the figure is a hand type, and it is remarkable for its versatility, as most types of articles can be produced on it. From its simplicity of construc tion and ease of manipulation it has proved a valuable asset to the small manufacturer, particularly for the production of knitted outer garments. The machine can also produce circular fabric, which is a useful point in the production of knitted gloves, in that the small bags or pockets for the hand and fingers can be made entirely seamless and in a perfect circle of loops. The needles can be arranged to give all kinds of rib patterns, and these can be shogged or given a zigzag appearance producing the rack stitch, which is a desirable feature of designs used for sweaters and sports goods. The hand operator can make the articles shaped as required by moving stitches to increase or de crease the width, and this facility enables novelties to be more readily produced than is the case with the larger and more cum bersome machines. It is also largely employed for knitted coats and costumes. This industry is found in many places far from the recognized centres, and is a suitable occupation for seaside resorts and for mining communities where the normal labour conditions allow little scope for the activities of women.

Miscellaneous Knitted Articles.

The circular principle of knitting is adapted to many purposes of smallwear. For example, in the making of ribbons and tapes a circular machine having only a few needles in the circumference is employed. For cords there may be only three or four needles in the circle, for narrow bands and tapes 16 to 20. When colours are introduced, attractive trim mings and millinery adjuncts are produced. With the circle a little larger, gas mantles are worked in the knitted stitch in the ramie or China grass yarn, and slightly greater widths bring in fabrics suitable for knitted ties, where a number of colour feeders are added along with patterning devices to give attractive motives. From 3 in. to 41 in. diameter the circular machine is used for the production of hosiery on the seamless principle, and the gauge is given as the number of needles in the circumference of the cylinder. The leg, foot, heel and toe can be produced entir: ly automatically except for a short join across the toe, the time required for a pair of full-length stockings of medium gauge being about ten minutes. One operator minds eight to ten of these machines, and this unit will produce from 4o to 5o dozen pairs of stockings per day. Taking 3i in. as a normal diameter, the gauges range from 68 needles in the cylinder to 300. A number of mills are now operating 30o and 32o needle 31 and 31 in. machines.

Cotton's Frame.

This gives the view of the Cotton's patent frame where the articles are made exactly to size and shape. This frame can be built to make 12 full-width garments at one and the same time, or 28 full-fashioned stocking legs. It has acquired a remarkable number of attachments to produce cross stripes of colours, vertical lines and patterns after the manner of added embroidery, openwork or imitation lace designs. Tuck patterns are also made, so-called because of the way in which certain stitches are tucked into the fabric unintersected by a new loop. In hosiery manufacture, the machines are divided into those which are adapted for producing the leg portions termed "leggers" and another set, the "footers," are specially equipped to produce the foot. These are usually grouped in "sets" of three leggers and one footer, as the footer having a lesser amount of knitting to do produces relatively three times as fast. Production of normal goods (not lace clocks or fancy effects) is from 4o to 45 dozen pairs per day per set.

The French Foot.

In the hosiery trade two divisions arise under the term of English foot and French foot. In the English type, the foot is made in two pieces, one-half covering the upper foot and the second portion the under foot, these being joined by seams along each side of the hose. In the making of this type of hosiery a sole machine is employed instead of a footer. The French foot portion is made on the footer in one piece, which is wrapped round the foot with a scam or join along the centre of the foot. By this system the pattern can be continued right round the foot, whilst in the English style the pattern formed in the rest of the hose is interrupted by this join at the side. Nearly all of the full-fashioned hosiery produced in America is of French foot type, which allows greater production. Splicing is a term adopted to indicate the extra thread of hard-wearing yarn inserted as an extra yarn at the heel and toe and along the foot bottom. This splicing also extends in many types about 21 in. up the back of the heel, and is often found halfway round the circle. This begins in a straight line which rather spoils the effect, and what is known as the tapered splicing has been introduced after the manner of a pyramid standing on its base, so that what is normally an objectionable feature is transformed into an item of ornamentation. Many variations of this pointed high splice are in use.

Circular Frames.

The English loop-wheel circular frame is constructed with spring needles arranged with the springs facing outwards round the circumference, and the fabric proceeds up wards to be coiled round winding-up rollers. This machine is specially adapted for making what is known as fleece-lined fabrics, as it has facilities for making fabrics where a thick thread floats on the back and is afterwards brushed and rendered fleecy. The machine can also be adapted for working imitation astrachan and fur-like fabrics, and it is also used for the thicker and denser textures suitable for suitings and overcoatings, the fabric having the knitted origin obscured by the brushing operation.The French or German circular frame is another type of spring needle circular, where the needles radiate from a centre and are set in a circle with the fabric proceeding downwards. This ma chine has been adapted for the production of plush and velvet fabrics, mostly in artificial silk, where the lustrous yarn is brought to the surface with a longer length of loop which forms itself into a pile which can be cut or left uncut as desired. American machine builders have worked steadily forward production of both spring and latch needle machines of finer gauge or cut. The results are borne out by the 30, 34 and even 4o cut machines in use—the latter having 4o needles to the inch. Due to the wide-spread use of rayon, or artificial silk, and the resultant tendency toward finer fabrics, machines, such as 32 and 36 gauge are considered obsolete while the 42 gauge (28 cut) machine ranks supreme for under wear fabrics of quality. These fabrics have a wide popularity for dress goods, and they afford one more instance of the way in which the knitted fabric is invading the realm of the older woven tex ture. The finer denier of artificial silk combined with the deli cately set mesh of the fine-gauge knitting machine make it possi ble to produce fabrics of gossamer-like consistency for every tex tile use. In the newer adaptations of the Jacquard principle to the circular machines all limits to the scope of knitted design have been broken down, and it is now possible to produce fabrics with a repeat extending the full width of the fabric.

Development of hosiery machinery in America was principally along the lines of circular machines of the automatic type. An example of such machines is found in one type which starts knit ting, and after finishing the garter welt, turns, knits it into the body of the stocking, knits in an imitation seam at the back (in simulation of full-fashioned goods), enters the splicing yarns in heel, sole and foot, and automatically knits in gores in the heel and toe sections. The stocking leaves such a machine fully completed except the toe join or seam and dyeing and boarding. Fully auto matic hosiery machines, although imported in large numbers, are manufactured in America in two plants, one of them being the largest manufacturers of this type of machines in the world.

(W. Ds.)