House

HOUSE, originally any structure built for human habitation; by extension the word is used at the present time in a much wider sense, as of a building which is the centre of activity of an organ ization (e.g., houses of parliament). Thus in certain universities, schools and colleges, dormitories are sometimes known as houses; and the term house mother or house doctor is used of the matron or physician of any group of people resident together. Owing to the close association, in feudal times, of a family with its place of residence or fief, the word house is frequently used of a family (e.g., house of Habsburg), and by a still further transference, of any group of people gathered together for any specific purpose (e.g., a theatre audience).

Prehistoric Dwellings.

The origins of the house as a human habitation can only be surmised. It is obvious that Stone age man, at least in the temperate climates, dwelt frequently in natural caves, and even at this early time, made distinct attempts to decorate his residence as the cave paintings along the Garonne in France and some in northern Spain prove. There are evidences, also, that forest dwelling tribes and those in tropical countries early developed some sort of hut construction, probably by plant ing sticks in the ground, in a circle, binding their tops together to form a cone, and covering the framework with thatch or leaves. Such primitive constructions are still used in many parts of the world, as in Central Africa; the wigwam type, common to many American Indian tribes, in which the covering was of skins rather than brush or leaves, or the dome shaped huts of the Indians of Tierra del Fuego preserve the same forms.At some ancient time the primitive cave dweller discovered that his cave could be enlarged and strengthened by constructing in front of it a wall of piled rocks, and roofing the space between the cave and the wall with logs or skins. Growing skill in this type of construction led to the development of such elaborate cave dwellings as those found on certain river banks in the south-west of the United States, whose date is unknown, but which are ob viously far earlier than the pueblo culture. Viollet-le-Duc (His toire de l'habitation humaine, 187 5) hypothecated similar com binations of cave and masonry dwellings as one of the universal primitive forms of Aryan houses. Thus the hut is the parent form of all timber houses, and the cave dwelling of those of masonry. Most of these houses were of one room, but with the development of a more complex civilization, sub-division became necessary and the plan was articulated. At first this seems to have been accomplished by merely combining several hut units within a single enclosure. Many remains of floors and foundations of such groups of round huts, probably of straw in some cases and of unbaked brick in others, dating from the Neolithic age, have been found throughout the Aegean world. Later, elliptical forms with sub-dividing partitions appeared, like that at Chamaizi in Crete, of about 2000 B.C., and the so-called tholos of the lowest stratum at Tiryns, perhaps even earlier. It is noteworthy that the richest tombs of the Mycenaean culture were of the tholos, or beehive type, and there is a universal tendency to make house forms follow contemporary or earlier culture.

Another form of development characterizes late Stone and Bronze age villages of northern and Central Europe, the so-called lake dwelling in which many rectangular houses, some of two or more rooms, were built upon a pile-supported platform over a lake. Modern examples of precisely similar types occur along many of the rivers in Siam, Cambodia and the neighbouring countries. In European lake dwellings, not only does primitive frame construction, a development of the hut type, appear, but also the use of crossed logs overlapping at the corners—the typical log cabin construction.

Egypt and Western Asia.

In the much more civilized culture in the vicinity of the Aegean two types of house plan made their appearance. The first is the block house, with all of the rooms under one roof and in a compact block; the second is the house with a court, in which the rooms open on to a court with or without a colonnade or open corridor. Egyptian models of houses dating back to the early empire show both types, but in Egypt the court type seems never to have been developed as it was in Europe and China, and the court appears most frequently as a garden or stable yard enclosed by walls on two or more sides, with the house proper often forming an L-shaped mass on the other two sides. Outside stairs to a flat roof are frequently shown in these models, and it is probable that houses of two or more storeys were common in the cities. Excavations of various town sites in Egypt, particularly in the Fayoum, have proved the accuracy of these models, and are continually revealing new details. The larger houses of the country-dwelling aristocracy are shown in many tomb paintings which reveal a general type in which a central residential block, with or without a colonnaded court, is sur rounded by a formal garden, around whose enclosing walls are built the stables and storehouses. There is much use of large windows, columns, awnings and a great luxuriance of decoration; the construction seems to have been largely of clay or unburned brick reinforced with a framework of timber or reeds.In the Aegean culture, both court houses and those in a single block are found. The great palaces of Cnossus, Phaistos (both c. 2000-1500 B.c.), like the more highly developed and architect ural palace at Tiryns (c. 'zoo B.e.) all have a court as their most important feature, but the plan of the town of Gournia shows simply a maze of crowded, close built rooms. Moreover, many paintings and terra cotta placques show Cretan houses as cubicle blocks, often in two storeys, with flat roofs and many windows.

The early Mesopotamian house, which remained fairly con stant in form over at least 2,000 years, and probably more, throughout the Chaldean and Assyrian periods, was of three types. The first, represented frequently in Assyrian bas-reliefs, is a de velopment of the conical hut, constructed, apparently, in un burned brick, and consists of a tall, narrow, dome form, sometimes set on a small square base. The second, also known from the reliefs, was probably the country residence of the well-to-do and is shown as a rectangular building or group of buildings with flat roofs, battlemented parapets, arched doorways and many long, low windows close to the roof, sub-divided by colonnettes. The third type, the city house, consisted of an assemblage of long, narrow rooms, with walls of immense thickness arranged around one or more courts. Some of these rooms may have been barrel vaulted in brick. Architectural decoration is of the simplest. What richness they possessed must have been produced by a lavish use of textiles.

The most complete idea of early Semitic houses is given in the description of Solomon's palace in the Bible (I. Kings, vii.). Timber was much used. Flat roofs were universal, and in the larger chambers they were supported by rows of wooden columns. Decoration was by means of repousse metal work applied to the wooden surfaces.

Classical.—In both classic Greece and Rome, the court type of house, that had appeared in Assyria, was brought to its highest point of development. Extensive remains of Greek houses have been investigated, especially at the Peiraeus, Priene and Delos. In almost all of these the house consisted of a group of rooms around a central colonnaded court or peristyle. In some there is indication of the existence of an upper storey. In the larger houses there was frequently a gallery across the front. There are only few evidences of the division between the andron and the gynaeceum, the men's and women's quarters; either the women's apartments were on the second floor, or else the division was only architecturally expressed in the largest houses through the existence of two or more courts. The most important position, at the end of the court opposite the entrance, was reserved for the reception room and the chief bedroom or the thalamos, the official centre of the house life. The remains of a large house of late Greek date exist at Palatitza in Macedonia. Here, not only were there multiple courts, but also long wings, or ranges of rooms, with colonnades along the front.

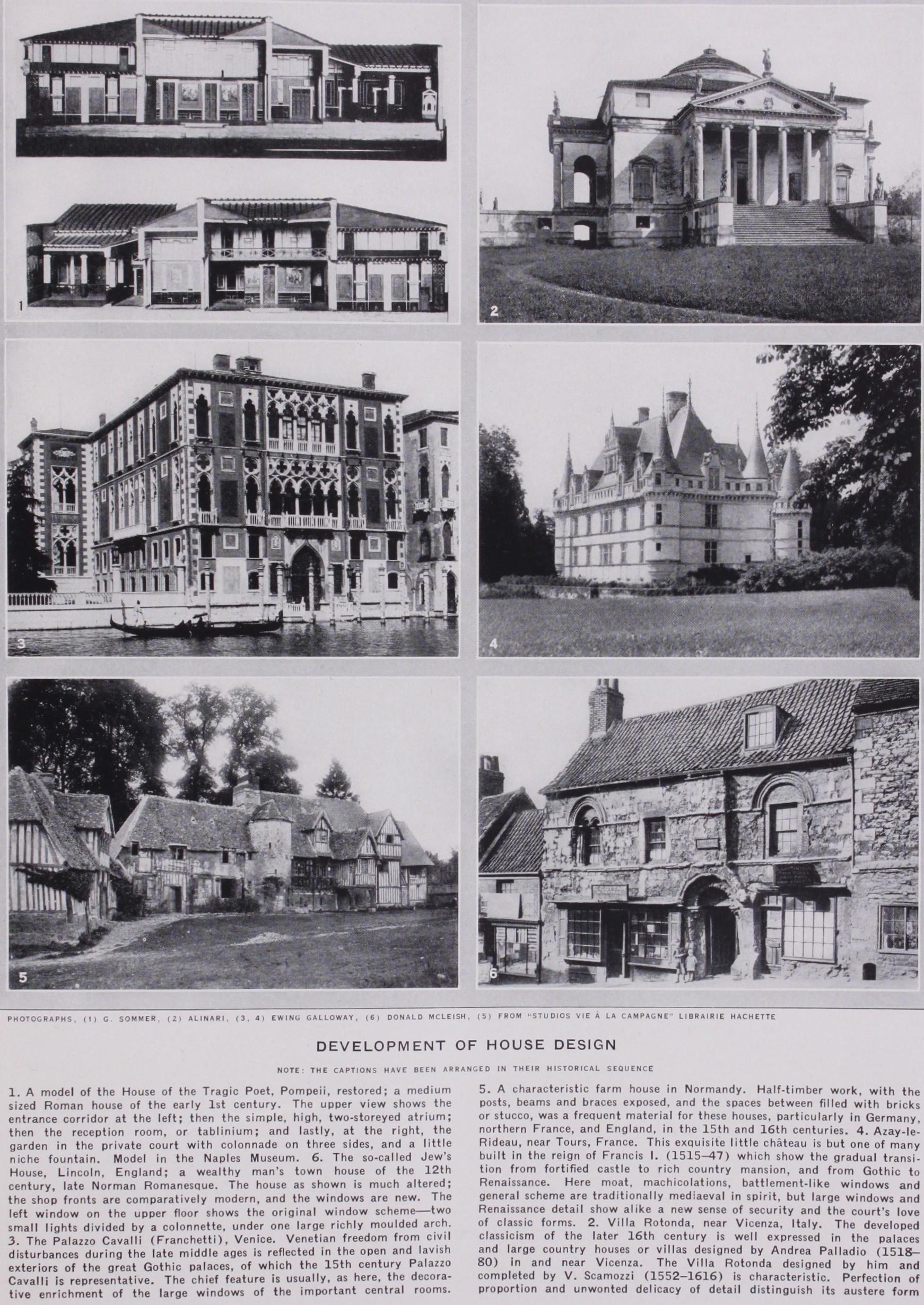

In the Roman house the court idea was superimposed upon an earlier tradition of a single room dwelling with a hole in the centre of the roof for the emission of smoke—the primitive atrium (q.v.). Prehistoric cinerary urns in the shape of these early houses have been found in various places in Italy, particu larly in the Alban hills. In the historic period, the atrium had already become primarily a court, with the living rooms around it, and the excavations at Pompeii have proved that by the 2nd cen tury B.C., at least in southern Italy, the typical Roman house comprised a colonnaded court as well. In the imperial period, the atrium, with its surrounding rooms, was reserved for business and official functions. Family life centred in the peristyle. Apart from detail, the general appearance of the large Roman house of the imperial era is almost perfectly reproduced in many of the cities of northern and central China to-day. Indeed, so close is this resemblance that Miinsterburg (Chinesisclie Kunstgeschichte) claims the presence of definite classical influence.

Variant types of Roman houses were the great country houses or villas, so well described in the famous letters of Pliny the Younger concerning his villas at Tusculum and Laurentium, of which many restorations have been brought together by H. Tanzer (The Villas of Pliny the Younger, 1924). Remains of such buildings are found frequently throughout the Roman empire. Another type is the farm-house, such as that discovered at Boscoreale, in which barns, oil and wine presses, storage rooms and the house proper were in one building around one main court. A vast provincial farm establishment in N. Africa, that of the Laberii at Uthina (dating from various periods from the 1st to the 4th centuries) shows a palatial central residence with many wings to take advantage of the view and prevailing winds, and separate small buildings for the farm. Another variant form was the great apartment house of several storeys which was the usual residence of the poorer free classes, not only in Rome, but in many of the more crowded centres. Indications on the marble plan of Rome which was prepared under Septimius Severus sug gest that these structures frequently surrounded a court in which was placed the stair tower that gave communication to the vari ous storeys. The fronts of these buildings were surprisingly modern in appearance; usually there were shops on the ground floor and rows of simple windows, often with projecting balconies above. The whole was usually faced with brick, unstuccoed, with the mouldings, etc., worked on the face of the brick itself. Recent excavations at Ostia have at last rendered possible definitive restorations (see G. Mars, ed., Brick Work in Italy, 1925).

Roman tradition continued unbroken through the Gallo-Roman time up to the Merovingian empire, and at Martres-Tolosanes, in south France, remains of large villas of this date, similar to those of Roman times, have been studied. Other interesting provincial derivations from the Roman stem are seen in the stone houses of Syria, vast numbers of which exist, dating from the 3rd to the 7th centuries, when the villages and towns seem to have been suddenly abandoned at the time of the Mohammedan conquest. These Syrian houses are sometimes roofed in stone and all of them are remarkable in the extent to which stone is used, not only for walls, but for doors, railings, screens, etc. There is gen erally an enclosing wall around a forecourt, with the house in a block at the rear, fronted with a colonnaded gallery.

Mediaeval.

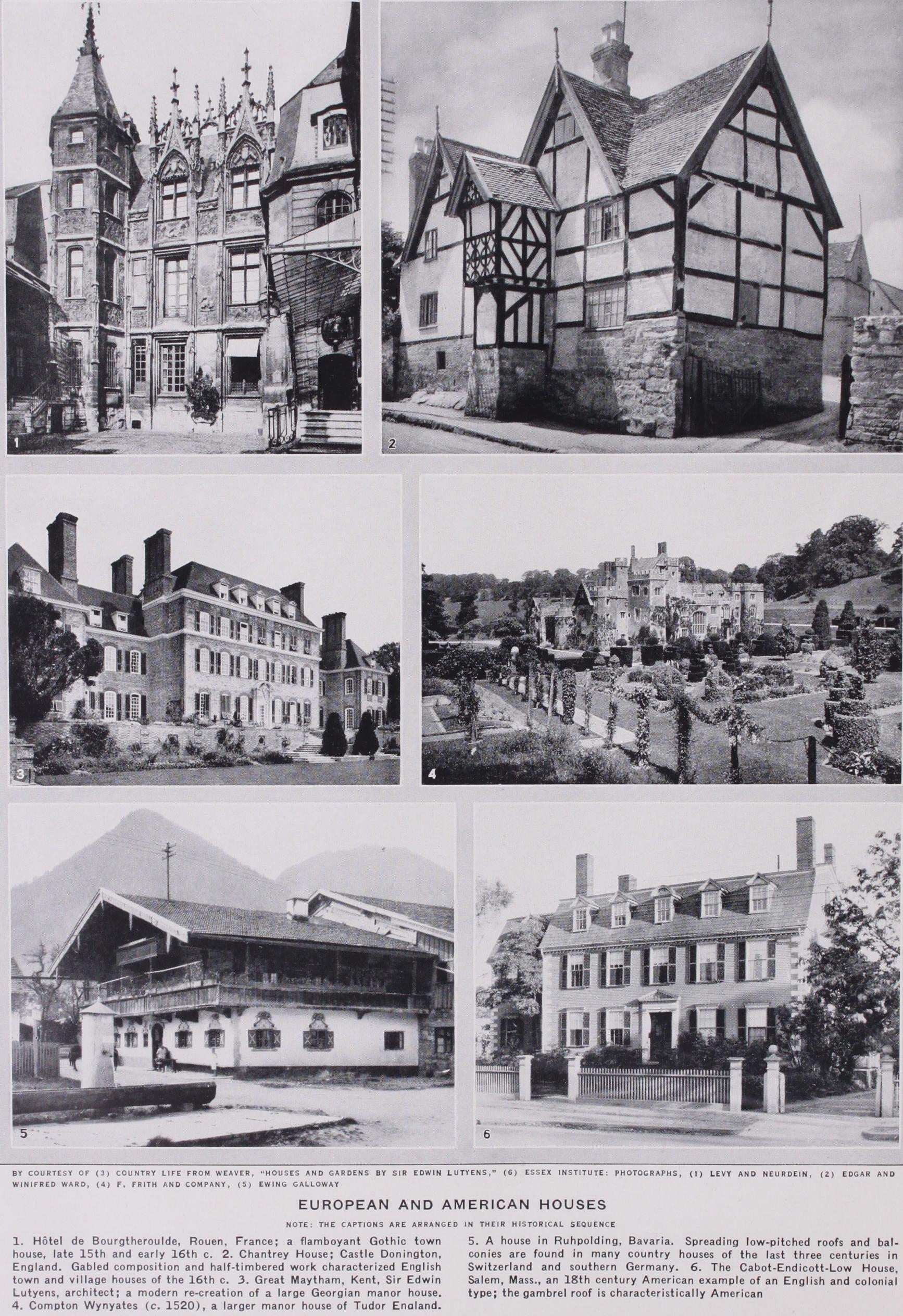

In Europe the growth of towns and villages dur ing the it th and i 2th centuries produced a new development of house planning. Country house design, on the other hand, out side of feudal castles and manors (see CASTLE), remained almost stagnant ; as far as is known the serfs' dwellings were mere huts with low walls, perhaps of masonry, or banked with earth and sods, and the roughest kind of thatched roofs. This type, evi dently once common, persisted into the i9th century in the huts of transient workers like charcoal burners or bark peelers in England, and the sod house or dug-out of the western plains of America. By the 13th century this condition was beginning to change, at least in France, and the hut was replaced by stone farmhouses and cottages, often divided into two or more rooms, with chimneys and fire-places and roofs sometimes of slate and sometimes of thatch. The further feudalism retreated the more the country house developed, and by the late Gothic period, all over north Europe, the wealthier peasants lived in highly de veloped farms, usually taking the form of a rectangular enclosure, entered by a gateway and bordered by barns, storage sheds and the house proper which was often in two storeys and well finished with windows and chimneys. In France such buildings were usually of stone, but in Switzerland, Germany and Scandinavia wood was the common material, either in half-timber (q.v.) or in "log cabin" or chalet (q.v.) construction. In towns the smallness of the lots forced an early development of compact planning in several storeys. Existing houses of the 12th century in Cluny show the scheme. Each floor is divided into two rooms separated by a light court and connected by a gallery. On the first floor was a shop with the kitchen behind, and stairs leading directly to the living quarters above. On the next floor was the main living room, with sleeping quarters behind, and above this, attics, under the roof. Usually there was a well in the courtyard and toilet accommodations are frequently found. In general standard of comfort, these houses of the 12th and early 13th centuries compare well with any built during the next Soo years, and it is noteworthy that the development during the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries was merely one of increased size and greater elaboration of the façade. Examples of such houses with masonry fronts exist in France in many of the fortified towns of Gascony, such as the Bastide at Mon Pazier, and at Amiens, S. Antonin, Avalon, Provins; and in England at Lincoln, the rectory at West Dean in Sussex and elsewhere. Especially noteworthy are the Musicians' House at Rheims (c. 1240), famous for its niched statues of musicians and the simple elegance of the treatment throughout, with tall, mullioned windows and an arcaded cornice, and the 12th century Jews' House at Lincoln with delicate Norman detail.In Italy, where cities were more highly developed, town houses were even further advanced, and it was during this period that the typical north Italian city palace, built around an arcaded court, with enormously high storeys, and many small coupled windows, and frequently with a projecting battlemented parapet, took form. The special conditions of Venice produced there a more open type of design, with a great use of long ranges of windows under Gothic tracery, rich projecting balconies and walls sheathed in coloured marbles. These, like the French houses, were often long and narrow in plan, but one or two rooms deep, with a court at the back. In all Italian examples, and in most of those in France, the main living floor was one storey above the entrance and the ground floor was reserved for shops and service rooms. In north Europe, in the 14th and 15th centuries, more and more houses, both city and country, were being built of half timber (q.v.), so that although stone or brick seemed to predominate in the 13th century town it was half timber which predominated in the 15th century town, as may be seen to this day in por tions of Rouen, Beauvais, Strasbourg, Hildesheim and Chester. The same period, moreover, saw the origin of the great burgher or wealthy free peasant's house, and the development of types for the nobility which were no longer mere castles or châteaux, but like the English manor houses, designed primarily for comfort. Of the important town houses, two still exist in perfect preservation, that now used as the Cluny museum at Paris (1485-9o), and the house of Jacques Coeur at Bourges (c. 1450). In both of these there is to be observed a growing sub division of the areas to give greater privacy and to separate the various functions of eating, sleeping and the social life. The planning is still, however, embryonic, with no grasp of corridor circulation and many stairs.

The same sub-division and the same struggle for convenience and privacy characterizes the entire history of the English house from 1400 to 1700. At first merely a great hall (q.v.) with service rooms at one end and private rooms at the other, the house rapidly developed into a plan which in all main respects is modern, with parlours, dining rooms, sleeping rooms, etc., all carefully differ entiated. The beautiful manor of Compton Winyates (c. 152o) shows the type; Kirby hall, by John Thorpe (begun 157o), and Hardwick hall, Derbyshire (early 17th century, John Smithson architect), show the complexity and growing symmetry of the English plan as well as the introduction of Renaissance ideas, and Speke hall, near Liverpool (17th century), shows the similar type treated in half timber. In all of these, lavishness of interior finish, by means of plaster and wood panelling, is a noteworthy feature.

The Renaissance.

The Renaissance house throughout Europe was a compromise between two conflicting influences; the tradi tional development of convenient plan ideas and the desire for classic symmetry. In Italy, where the mediaeval large house had always been designed on monumental lines, the conflict was not strong, but in north Europe late Gothic plans were definitely asym metrical, and the conflict was bound to lead to compromise. The best of the compromises was that achieved by the English during the late 17th and i8th centuries under the influence of Inigo Jones and his followers. In France, through the craze for classicism and the influence of the court, convenience markedly suffered, so that there the average large 14th or 15th century house had infinitely more real comfort than that of the 17th or 18th century. There was, however, a corresponding gain in elegance, and individual staircases, rooms, etc., reached a standard of excellence of design, charm of detail and beauty of execution which has seldom been equalled. There was also an enormous ingenuity in planning, a growing elimination of waste space and a remarkable integration of interior arrangement and exterior effect. The greater number of these large houses, or hotels, which give the character to so many French towns, were built between the street and a large garden, with an impressive gateway leading to a courtyard and the house rooms beyond. The Hotel d'Amelot, in Paris, by Boffrand and the Hotel Lambert, Paris, by Levau (1640), are examples of the typical "Louis" house. The finest of the interiors, outside the royal palaces, are those of the Hotel Soubise (early i8th century) and the Hotel de Sevigne (c. 166o), now respectively the National Archives and the Carnavalet museum, both in Paris.Meanwhile, in America, different conditions were developing from English precedent a slightly different type of house, more compact, and usually less monumental. In the north, the house of a single block, with two or four rooms to the floor and a central chimney (e.g., Capen house, Topsfield, Mass., 1693), or the larger houses with end chimneys (e.g., Warner house, Portsmouth, N.H., c. 172o) became the accepted type. In the south, where social conditions were more like those in England, the houses more closely resembled those of the mother country. Thus Mt. Airy, Va. (1758), of cut stone, and Westover, Va. (c. 173o), could be almost duplicated in many English counties, and Washington's home at Mt. Vernon, with its multitude of service out buildings, slave quarters, etc., is but a version in wood of a com mon English type. Close contact with France during and after the American Revolution, French architects working in America (e.g., l'Enfant), and the fact that many early American architects trav elled widely in France (e.g., Bulfinch), led to the development in America of the French monumental house plan, as in Woodlands, Philadelphia (remodelled 1788), and the Gore house, Waltham, Mass. (1799-1804, possibly by Bulfinch).

Modern.

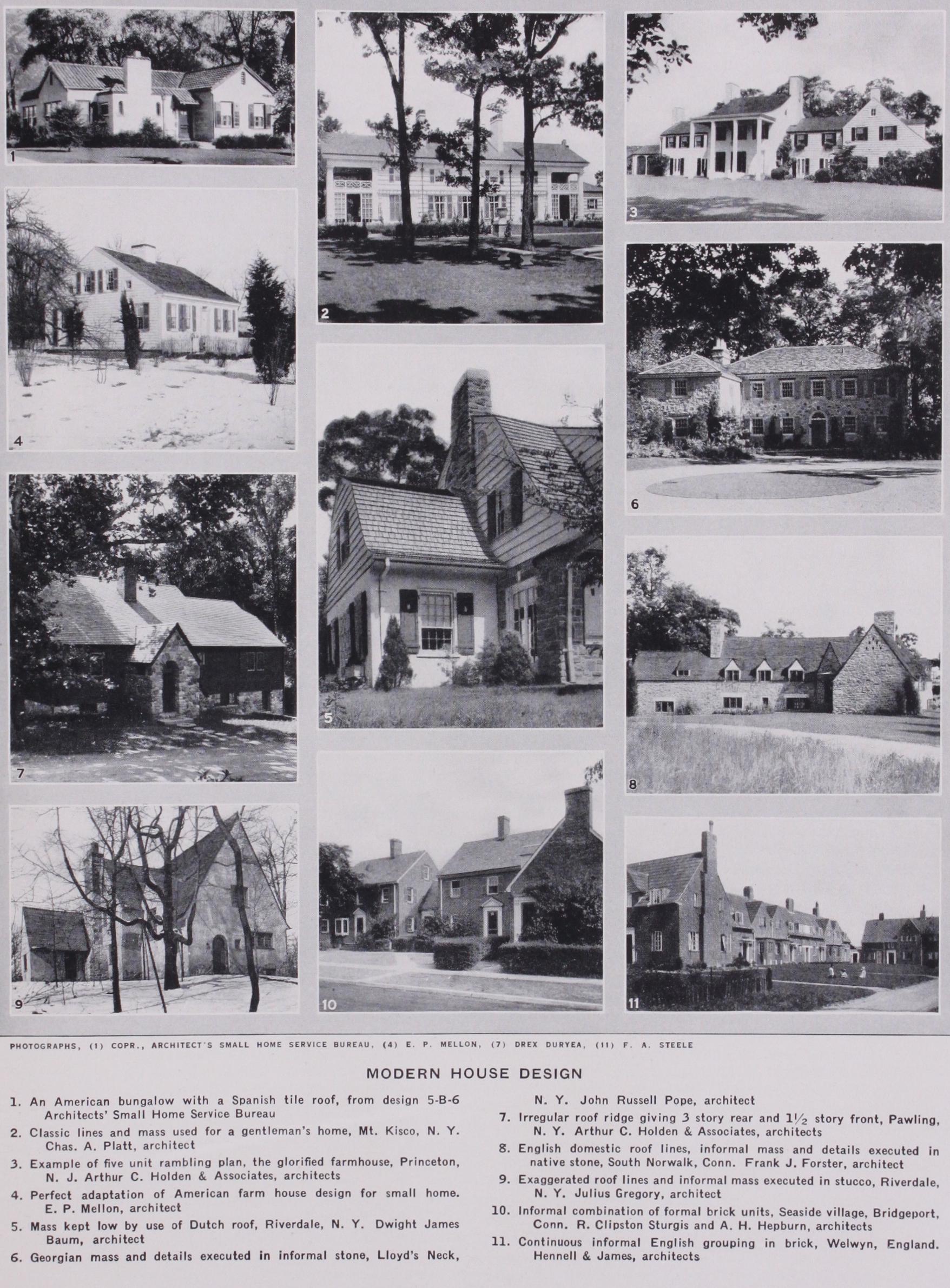

The industrial revolution produced a synchronous revolution in house design all over the western world, especially in towns and cities. The influences at work were confused—increased land values, due to sudden city growth, congestion of popula tion and a generally rising standard of comfort, with the additional facilities provided by the coincident development of plumbing, lighting systems, etc. Up to the middle years of the 19th century the house of western civilization had been but a development in a direct line going back to the 12th century. Since the industrial revolution ideals and aims have been totally different (see SOCIAL ARCHITECTURE). In general, the area for each family has dimin ished, while the number and differentiation of rooms has increased. An inevitable result has been the complete alteration of the ap pearance of modern cities as apartment or tenement dwellings have, to a large extent, replaced the individual house. Equally significant is the development in the outskirts of all great indus trial and commercial centres of suburbs characterized by the crowding together of small individual houses on small lots.In the design of these houses (see HOUSE PLANNING) as well as in the industrial housing surrounding many factories, and in the larger country houses of the more well-to-do, there has been a gen eral advance. Waste spaces have been reduced and the problem of furnishing adequate communication, and at the same time pre serving privacy, has been to a great extent solved. Moreover, the service arrangements have been simplified and perfected so that every possible waste of time may be avoided in serving meals or caring for the house. The lack of an inhibiting tradition in much of America has remarkably aided this development and, more and more, such originally American ideas as a multiplicity of bath rooms, the use of a central heating system, and the evolution of space-saving kitchens and kitchenettes are appearing in the newer houses, not only of England, but of the entire continent of Europe. No such development or standardization of architectural treat ment has occurred. A chaos of varying styles is evidenced in con temporary American building; colonial, "English," "Italian" and modernist houses stand on the same street. In England, the stronger traditionalism characterizes the greater number of mod ern houses, with Georgian or Tudor forms predominating, but both frequently coloured by a modern style freedom. On the continent of Europe, generally, the present (1928) tendency seems to be almost universally towards the most radical and modernistic treat ment, with cubicle directness and simplicity replacing any search for a more esoteric or sentimental beauty. In apartment house de sign (see SOCIAL ARCHITECTURE) the stringent limiting condi tions have exerted a controlling influence that is more and more producing a similarity of type, whatever the architectural style.

In areas not deeply affected by the industrial revolution, as in most of the Mohammedan world (see MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITEC TURE), and in Asia generally, house design carries on traditions frequently centuries old. Thus the modern Moroccan house, with its colonnaded court and flat roof, is a direct descendant of the court type of ancient Rome and Syria. Even the separation of the house into a public and private portion, or harem, bears a simi larity to the old double centre in the atrium and peristyle of Rome. In Egypt and Turkey, however, the court type has largely gone out of existence, and has been replaced by the single block type of house, frequently with a large central hall, often con taining a fountain which recalls the use of water in ancient courts. In Japan, also (see JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE), the single block type of house is found to be universal; the house is usually a long and rambling structure, tile-roofed, sometimes in several storeys. The sliding interior partitions, the matting floors, and the exquisite use of wood make interiors of delicate and sophisti cated charm. In China, on the other hand (see CHINESE ARCHI TECTURE), the court type is the rule where European influence has not modified native ways. The use of colonnaded galleries and large symmetrical halls often gives a markedly classic appearance.

See also ARCHITECTURE, ATRIUM, HALL, HOUSE PLANNING, STYLE, SOCIAL ARCHITECTURE, and the various articles on the history of architecture, described under the heading ARCHI