Housing in the United States

HOUSING IN THE UNITED STATES Most of the factors which have operated to produce housing problems in Europe are found also in the United States. Houses dating back to the Middle Ages do not, it is true, complicate the American picture, nor, as a rule, the dark and narrow streets which went with them. On the other hand, the extremely rapid development of the country, the individualistic pioneer spirit of its citizens and the plentifulness of lumber, have resulted in a mass of carelessly built housing which, when neglected for twenty or thirty years, presents a picture of dismal blight. The United States probably has more acres of sheer dilapidation per thousand inhabitants than any other civilized country.

The chief cause of bad housing is economic, whether at home or abroad. Modern industrial society produces a distribution of income which, in times of normal prosperity, permits about a third of the population to obtain new homes of adequate stand ard through the workings of supply and demand. That means, in the United States, about ten million families. When this group live in older houses, it is safe to assume that such houses have been kept in good repair and supplied with modern conven iences. Then there are another third living in older houses, but not necessarily bad ones. Many of them are poorly designed, or built too close together on the narrow lots which have been all-too-prevalent, or they are shabby and out of date. This is the income group for whom limited-dividend companies should be encouraged to build.

The lowest economic third, another approximate ten million families, are those who live in the oldest, most dilapidated, crowded and uncomfortable houses, which no one else wants. They are powerless to better their condition unless the provision of wholesome housing for them becomes a public responsibility. European countries have been working on this principle for the past generation or so. In the United States, in any large sense, its recognition dates from Until a halt was called on immigration, the growth in the population of the United States had been extraordinary. Few doubted that it would continue forever. Every small town was believed destined to become a great metropolis. It did not mat ter that a ring of blight surrounded most central business districts, produced by the movement outward of families in comfortable circumstances who had formerly lived there. For would not all these deteriorated eyesores of conglomerate usage soon be torn down to make way for expanding business and in dustry? Meanwhile new waves of immigrants were flowing in to occupy every nook and cranny. The landlord was making a profit until the happy day should come when he would make a fortune.

Stopping immigration stopped the flow. The majority of those caught in the bad stayed there. For the first time a generation of young men and women have grown up who were born and bred in American slums and know no other home.

It is now generally understood that our population growth will be slow for the next few decades and will reach stability about 1960. After that, city growth, if any, will have to be qualitative. If a drifting policy is pursued, municipal bankruptcy lies not far ahead. Because the more successful families will continue moving outward to build new homes, where they have more light, air and space, leaving their deserted homes to form more rings of blight, and forcing the city to keep on building and maintain ing new streets, sewers and schools, without any increase in the number of taxpayers.

The more rapid city growth in the United States and its sudden ending have created a more acute economic necessity than is found abroad, to rebuild and reclaim our blighted cities or to abandon them as hopeless. An important school of thought ad vocates the redistribution of population and industries into new communities, planned from the start for health, efficiency, and the amenities of civilized life.

History.

During the first two centuries of building within the confines of what is now Continental United States, much housing was erected, good and bad, without its being regarded as a public problem.The first voice raised to connect insanitary and overcrowded housing with the origin and spread of epidemics was that of Gerritt Forbes, a New York sanitary inspector, in a report for 1834. Of the century which has passed since, it took the first third to get by the stage of surveys and talk, before any steps were taken to improve the shocking conditions revealed.

The twin results of a generation of effort were the establish ment of a Board of Health in 1866 and the enactment in 1867 of a Tenement House law, both for New York City. For the first time it became unlawful to build a tenement house covering i 00% of its lot. There had to be a io-foot yard in the rear. Living quarters could not be rented which were completely underground. The ceiling had to be a foot above curb level. There must be running water on the premises, though a back-yard spigot fulfilled that requirement.

Thus, housing reform in the United States, as had been the case in England somewhat earlier, began with sanitary provisions and an exercise of the police power, laying certain minimum require ments on builders and landlords in the interest of public health.

It was natural that progress should start in New York, for the problem there was larger in quantity and more acute as to quality than anywhere else. Gradually other seaport cities where immigrants landed, and later the inland cities where they found employment, began to be conscious of similar problems of their own. Records of housing investigations by public or private committees or associations, resulting in restrictive legislation, are found during the nineties in Boston, Philadelphia, Wash ington and Chicago.

It must be kept in mind that such legislation is not retro active. It may impose fairly high standards on future buildings. It does not outlaw buildings already in existence, though it may require landlords to put in certain improvements which are not too expensive. Water and sanitary installations can be forced, but not structural changes. When the New York 1901 law went into effect nearly 700,000 families lived in existing tenements. Those built before 1879 were full of windowless rooms. Those built between 1879 and 19O1 had side windows opening on long narrow courts :—the so-called dumbbell design. There were 67,000 of these buildings still in existence with 500,000 dwelling units after 34 years. This rate of demolition would give them at least a century of life after being officially declared obsolete. The fact is characteristic. Blighted neighbourhoods produce stag nation so far as voluntary demolitions and replacements by pri vate enterprise are concerned. Investors build on new land, or in prosperous neighbourhoods, whether business or residential, where everything has to be up-to-date. A neighbourhood which has started sliding cannot lift itself back by its own boot-straps.

Meanwhile, awareness of housing troubles had spread to other cities from the 189os to the War period, and was resulting in numerous surveys and reports and in a considerable amount of restrictive legislation, state or municipal, largely modelled on the New York Tenement House law. Some of the later ones, such as the state-wide Housing Acts of Michigan, 1917, Iowa (1919), California (19o9-1919) and Indiana (19o9-1917) and the city code of Minneapolis (1917), went considerably beyond it in re quirements as to open space and modern improvements. During this period the National Housing Association, devoted to the spread of restrictive legislation and building by private enterprise, exerted a profound influence on the housing thought of the coun try. In the later years, the Children's Bureau in Washington be came aware of rural housing problems and made some useful studies in connection with infant mortality and child welfare.

It must not be thought that during all this time there was no effort of a positive sort to produce good homes for working men. Employers built housing for their employees, sometimes because they had to, in which case the result was usually pretty bad, sometimes because they were honestly interested in their em ployees' welfare. The Pullman experiment in Chicago, much dis cussed during the '9os, was wrecked on the rock of paternalism. Alfred T. White built model tenements in Brooklyn from 1877 to 189o. The Boston Cooperative was started in 1871. The Phil adelphia Octavia Hill Association, which repaired and managed old houses, dates from 1896. The Washington Sanitary Improve ment Company and the New York City and Suburban Homes Company, both with voluntarily limited dividends, were of the same period. The Washington Sanitary Housing Company dates from 1904 and Cincinnati Model Homes from 1908. Then there was quite an outburst of limited-dividend housing companies sponsored by Chambers of Commerce in the early years of the World War. Most of them were short lived. Bridgeport had one of the best. With the exception of the Washington Sanitary Housing Company, which operated under a Congressional Charter limiting its dividends to 4%, which was later cancelled because it could not raise money at that rate, all limited-dividend companies in the United States were of the voluntary sort until the New York State Housing Act of 1926 set up a class of limited-dividend housing companies for that State which in return for certain privileges, were legally limited to 6% dividends and were under State control as to management and rents.

The War and Post-War Periods.

War housing undertaken by the Federal Government during the War period, 1917-1918, for war workers not otherwise provided for, introduced something entirely new in the United States. Knowledge that the British were housing their war workers in well-planned, well-built garden suburbs, was at least one reason for building permanent housing in attractive surroundings instead of wooden barracks. Plans were made for many thousand houses by the Shipping Board and the United States Housing Corporation in the Department of Labor, but owing to the unexpectedly quick termination of the War, only 16,000 were completed, all of which were eventually sold, some to the tenants (which was socially useful), some to the employers (which may have been useful) and some to real estate firms who profited from the housing shortage.While the War projects were under way, a considerable support developed for a policy of permanent government assistance on a national housing program. Evidently its roots had not gone deep enough, however, to withstand the impact of the wave of re action which followed the Armistice. Private business enterprise was in the saddle.

The post-war housing shortage caused acute suffering in many places. Remedial measures, such as rent restriction, were adopted here and there. (New York City, the District of Columbia and the State of Massachusetts were examples of different types.) Tax exemption for a specified number of years and to a limited amount, in order to stimulate private residential building, was chiefly employed in New York City, where, since there was no control of rents or quality, the result was to enrich the specula tive builders, at an enormous expense to the taxpayers, with no socially useful result beyond ending the numerical shortage more quickly than would have happened without it. The momentum of the movement for restrictive legislation along pre-war lines died out under the pressure of the housing shortage, but consid erable of it was transferred to the spread of zoning, following the enactment of the New York ordinance and those of Berkeley, California and Columbus, Ohio, in 1915 and 1916. City planning and zoning, with Federal moral support furnished by the Housing Division of the Bureau of Standards, made rapid progress through out the country during the post-war decade.

Meanwhile, California (Veterans Farm and Home Purchase Act, 1921) had developed a really interesting method of aiding its war veterans to attain home ownership, without expense to the taxpayers, by giving them the benefit of cash purchase (by the state), low interest rates and long amortization period. The total number of houses financed or approved has been about 19,00o, and the total issue of housing bonds has reached $80,000,000.

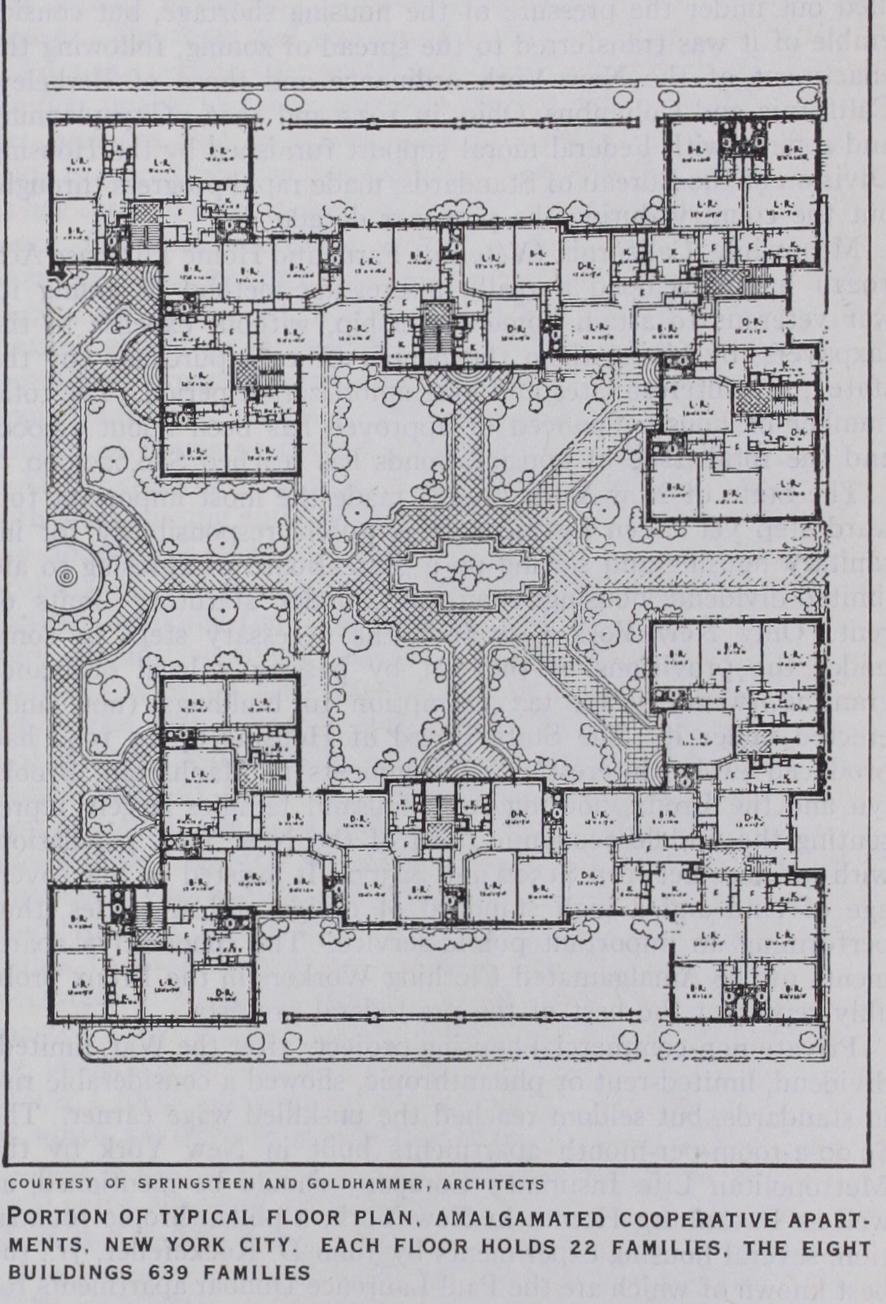

The State of New York (1926) made the most important for ward step yet taken by recognizing public responsibility for in sanitary housing and setting up a State Board of Housing to aid limited-dividend housing companies, under statutory limits of rent. Only New York City took the necessary steps to come under the provisions of the Act by passing a local ordinance granting twenty years tax exemption to buildings (not land) erected under it. The State Board of Housing up to 1932 had produced twelve interesting developments in Manhattan, Brook lyn and the Bronx, housing two thousand families largely repre senting the middle economic third of the New York population, with incomes between $150o and $2500. It insisted on low cover age of land and a high standard of design and amenities, thus performing an important public service. The cooperative apart ments of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers in the Bronx prob ably represent the best of the pre-federal projects.

Private non-commercial housing projects after the War, limited dividend, limited-rent or philanthropic, showed a considerable rise in standards, but seldom reached the unskilled wage earner. The $9.00-a-room-per-month apartments built in New York by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company should be mentioned, as well as Lavanburg Homes in New York, a philanthropic founda tion, several housing experiments by John D. Rockefeller, Jr., the best known of which are the Paul Laurence Dunbar apartments for Negroes in New York, two large developments in Chicago, Mar shall Field Garden Estate and Michigan Boulevard Garden Homes (the latter for Negroes). Sunnyside in the Borough of Queens, New York City, and Radburn, a new community on Garden City lines in New Jersey, both by the City Housing Corporation, as well as Chatham Village by the Buhl Foundation in Pittsburgh, were built for white collar tenants in the middle group or higher.

Era of Federal Participation.

As the War pushed the Fed eral Government into housing activity for the first time, so the De pression brought it back. The Emergency Relief and Construction Act of 1932 authorized the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to make loans to limited-dividend housing companies, under ade quate state or municipal regulation as to rents, charges, capital structure, rate of return and areas and methods of operation.Only New York State, with its 1926 legislation, met these terms when the act was passed, but State Housing Boards with similar powers were set up in 13 states during the next two years. A number of carefully prepared projects received approval by the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, but the organized opposition of real estate interests was so strong, that only one obtained a loan. That was Knickerbocker Village on the Lower East Side of New York, erected by the Fred F. French Company, which houses 160o families on two city blocks in twelve-story apartments, with automatic elevators.

In the spring of 1933 it became known that the Roosevelt Ad ministration was planning something more comprehensive in re spect to housing. The National Industrial Recovery Act, approved June 16, 1933, which set up the Federal Emergency Administra tion of Public Works, provided in Sections 202 (d) and 203 (a) that the Administrator should prepare comprehensive plans for the "construction, alteration or repair under public regulation or con trol of low-cost housing and slum clearance projects" and "with a view to increasing employment quickly (while reasonably secur ing any loans made by the United States)" the Administrator or his designated agency may construct, finance or aid any such project. To states, municipalities or other public bodies, not only might loans be made, but grants up to 3o% of labour and materials employed in the project: Within a few weeks the Hous ing Division was organized in the Public Works Administration.

Early efforts of the Housing Division were centred on limited dividend projects, which proved disappointing. Public opinion was not sufficiently developed throughout the country for dis interested local groups to prepare them wisely and in quantity. Over 500 applications were received, but only seven have been approved and carried out. Many were well intentioned, but im practicable. The majority were efforts to unload unsalable land or services on the Government.

In the summer of 1933, not a single State or local public housing authority, eligible for grants as well as loans, existed in the United States, nor did any State have the legal power to ap point one. The legislature of Ohio passed the first enabling act in Sept. 1933. Six years later such laws had been enacted in 38 States and nearly 25o State, county, and local public housing authorities had been appointed.

Early in 1934 it was decided to establish the Federal Emergency Housing Corporation to acquire land, build and operate directly. Legal questions delayed action for several months. After that difficulty was surmounted a judicial decision in a Federal Dis trict Court in Kentucky, affirmed by the Circuit Court of Appeals, denied that housing was a public purpose for which the Federal Government could acquire land by condemnation. The case was not carried to the Supreme Court. In some instances slum sites were acquired by purchase. In others, cities condemned the prop erty. The highest court of New York State ruled that slum clear ance and erection of housing for low-income families were public purposes for which the New York City Housing Authority could exercise the power of condemnation. This decision was followed by similar ones in a number of other States.

By the end of 1935 the seven limited dividend projects housing 3,200 families were completed and occupied. And 51 Federal housing projects in 35 continental cities, the Virgin islands and Puerto Rico were under way or authorized. At that period the regular public works set-up established by Congress provided for a 45% grant, and the balance at 3% interest, with a 6o years' amortization period. Rents resulting should be within the means of unskilled and semi-skilled workers. Physical standards include abundant air, sunshine, grass, and trees. Recreation needs, espe cially for children, are recognized, and the importance of socialized management. This demonstration program has produced 21,77o small well-built modern houses and apartments, completed between 1936 and 1938. More than half are on slum sites. Nearly half are occupied by Negro tenants.