Housing

HOUSING. The word housing has a general meaning cover ing conditions and statistics applying to all the dwellings of the community. The word has also acquired more limited and special meanings. It is used to refer to the problem created by deficiency in number, or defects in condition of the dwellings which are available for the poorer members of the community; and in a more technical sense it is employed to signify the housing of the working classes undertaken under the various acts of Parliament which have been passed to deal with the problem.

A housing problem, which differs in character from other prob lems due to poverty, has arisen so generally in modern civilized countries, that it is worth while to consider what are the various conditions in connection with dwellings which together account for the fact that the housing problem differs in kind as well as in extent from problems arising from lack of food, clothing or other necessaries of life.

High Costs: Permanence: Rent.

The three most important of such conditions are: I. The high initial cost of even the smallest family dwelling which will satisfy modern standards.2. The permanent and immovable character of houses when erected.

3. The custom by which the majority of consumers of this particular commodity borrow their house, instead of buying it, paying for it a periodic rent.

The cost of even a small modern dwelling is quite beyond the reach of the vast majority of those who set up a family home. Many will not accumulate during their lifetime a capital sum suffi cient to secure the unencumbered ownership of a small dwelling. Many others who might raise the cost have other more tempting uses for their capital, or prefer not to hamper their mobility by the ownership of their house. Owing to the high cost, the majority of occupants must depend on living in dwellings built by those who have command of capital; many prefer to do so.

The permanence of the structure, and the impossibility of moving it from place to place, further differentiate the dwelling from other necessities, and in fairness to the earlier tenants, in volve that the repayment of the capital cost be spread over a very long period. The greater part of each rent payment consequently represents interest on the capital invested, or other current out goings, and only a small portion represents an instalment paying off the capital cost. Periods of twenty to thirty years are com monly adopted for systems of purchase by instalment, while forty to sixty years are usual over which to spread the repayment of loans for housing purposes to public utility societies and local authorities. Even these longer periods do not represent the full life of a well built dwelling house ; many last for centuries ; and it is commonly accepted that the average useful life of small dwellings built during the last century may be taken at about eighty years. This long period of use or consumption gives op portunity for the play of many factors disturbing to the value, or rent-earning capacity of dwellings ; these involve the owner in risks which hardly arise in connection with other classes of prod ucts bought and sold across the counter. Considerable changes in the standard of living, of accommodation and of sanitary equipment may take place during the life of the building. The general introduction of internal plumbing and sanitary conve niences, the more recent provision of bathrooms, together with the demand for more sleeping accommodation, and a greater degree c f amenity and air space about dwellings, are examples of the changes which have been operative during the last half century. The character of localities also changes ; centres of employment may cease to operate, or move to other districts, leaving houses no longer wanted. On the other hand extensive new industrial de velopment may take place in the immediate neighbourhood of good houses bringing dirt and confusion; and the dwellings may become less attractive to good tenants than when they were erected. This may be followed by a general depreciation of the character of the neighbourhood and the value of the houses. Apart from such cases, the influx of a few rowdy or dirty tenants has sometimes proved sufficient to create bad conditions which spread from dwelling to dwelling driving away better tenants and resulting in a general depreciation of the property. The makers of all products and those who deal in them take the risk of changes in value occurring during the course of production or sale; but the long life of a dwelling house involves risks of a quite different order. During the last half of the 59th century, when conditions in Great Britain were fairly stable, there were three tendencies noticeable which affected the rent of dwellings. The standard of accommodation tended to improve ; such a tendency might depreciate the value of houses old enough to fall materially below the current standard. The rate of interest on capital tended to fall ; thus reducing the rent required to give a remunerative re turn on a given outlay per house. On the other hand the cost of erecting new dwellings tended to increase, involving an in creased rental per dwelling. The financial disturbances caused by the Boer War and other reasons arrested the fall in the rates of interest. Apart from such disturbances it is probable that similar tendencies would operate during long periods of fairly stable conditions.

The supply of small dwellings has seldom for long exceeded the demand and has frequently been insufficient to meet it and during the period referred to the value of the older cottages has on the whole risen in sympathy with the rentals of the newer ones to a greater extent than it has been decreased owing to in ferior standard or reducing rates of interest ; and it is generally true that rent of dwellings gradually rose during that period. This fact among others caused cottage property to be regarded generally as a profitable investment. Various changes in legisla tion, in the character and equipment expected for dwellings, and in the consequent responsibilities of the owners, were having the effect before the war of diminishing the relative attractiveness of this class of investment. The concurrent increase in alter native openings for the small investor to place his money with reasonable security and return has been an important element in this change. Violent fluctuations in rates of interest, cost of pro duction, and values of money, such as have followed the Na poleonic wars and the recent World War, introduce quite new fac tors. Periods arise in which the cost of building and the rate of interest which must be paid for capital are so high, and their maintenance at these rates so improbable, that even if adequate rentals could be secured at the moment, there must be consider able risk that such rentals could not be maintained. It must be anticipated that the return to stable conditions in the world will result in a rapid fall in costs and rates. Consequently there will be no prospect of maintaining rents over a sufficient period to repay the capital cost with interest, in competition with dwellings erected at lower cost with cheaper capital.

The permanence of dwellings also brings into play the powerful influence of custom. The regular payment of rents over a long period sets up a customary standard of value. A certain rental, say six shillings a week, becomes habitual; and any higher rent than the customary one is regarded as exorbitant. This influence is one of considerable strength in many places, tending to obstruct the adjustment between rentals and the cost of production or rate of interest. The continuance of low customary rentals for estate or tied cottages in many rural areas has greatly increased the dif ficulty of securing or maintaining the needed houses for the work ing classes. The conditions arising from the permanence of the dwelling are intensified owing to the impossibility of moving it from place to place. Many circumstances constitute the ownership of his dwelling by the occupier a considerable tie : the majority of men frequently change their place of employment. Change of ownership is liable to involve capital loss on each occasion : it is difficult to realize on a forced sale of a single house as good a price as that which the purchaser had to pay when he desired to obtain possession of it. The expenses of sale and transfer are also considerable. Ownership, moreover, involves responsibility for upkeep and liability from time to time for comparatively heavy outlays for repair or adjustment to changing conditions. Many of these expenses fall with special weight on the owner of one dwelling, while they are more easily provided for by the prop erty owner who can average the risks, and deal with larger blocks of houses, reducing considerably the incidental expenses per dwelling. These reasons tend to restrict the number of people willing to own their own dwellings. On the other hand, occupying ownership promotes care for the dwelling, tends to reduce main tenance costs, and confers a degree of stability and responsibility on the owner which constitutes an education in citizenship, and from many other points of view is eminently desirable.

Hiring of Houses.

Arising out of the conditions already described there has grown up the general custom of hiring dwell ing houses. Peasants have usually hired from the landowner ; in the case of agricultural labourers frequently through the farmer; while in urban areas property owners have supplied the need re garding the building and letting of dwellings as a sound invest ment. As regards those occupiers who rent houses for convenience rather than from necessity, the system presents little difficulty in normal times. If in any place or period conditions temporarily render the provision of dwellings to let not sufficiently attractive, such persons, if need be, can build for themselves. As regards the majority of people who must depend on renting dwellings the position is, however, different. Property owners will only provide dwellings in numbers and of a character for which they can see a reliable prospect of securing remunerative return. That means rentals adequate to pay the interest on the outlay, to provide a sinking fund to repay the capital cost, and leave something to cover insurance against the many risks involved. Where such prospect does not exist, house shortage is likely to arise.The increasing standard of accommodation, sanitary equipment, or amenity, is one which is set by the community generally. Un fortunately it does not always represent an effective demand on behalf of poorer tenants. Occupants become accustomed to in ferior conditions in dwellings, and easily sink to a low standard of cleanliness and decency. There are, especially in large towns, numbers who will put up with inferior accommodation rather than pay a small additional rent for better dwellings. Considerable numbers of obsolescent houses tend to linger in use by such ten ants after the period when they should be destroyed as being below the minimum standard of the day. Public opinion and the sanitary authorities seek to enforce improved standards; on the other hand, among a large section of the population an effec tive demand, at rents which would render the provision of dwell ings up to the improved standard remunerative, does not exist. The individual property owner cannot take the risk of providing up-to-date dwellings in excess of the effective demand. It is these conditions which give rise to the housing problem : how to secure the erection of sufficient dwellings of an up-to-date standard for the poorer sections of the community, so that the demolition of dwellings no longer considered fit for occupation may proceed, and the occupants be removed from the unhealthy and degrading conditions which the tenancy of such dwellings involves. To solve this general housing problem many efforts have been made by legislators and philanthropists ; but before referring to them it is desirable to touch on the special housing problem created by the World War which has overshadowed and in a sense absorbed the general problem.

General House Shortage.

In many countries the cessation of house building was almost complete for periods varying from four to six years. Naturally there resulted a shortage of all kinds of houses. Exception should perhaps be made of those at the larger end of the scale ; for the general reduction in personal means, owing to war losses, monetary depreciation or taxation, has reduced the effective demand for the larger houses below pre war level, which has incidentally tended to increase that demand for the middle class of houses. Not only was this shortage of exceptional character, but the difficulties of making it good were unusually great. The mobilization of much skilled building labour for war, or war work, the losses occurring among these crafts men in the belligerent countries, and the transference of many to other occupations greatly reduced the amount of trained labour available for the work. Recruitment of apprentices to the various crafts also practically ceased, normal wastage was not made good, and at the end of the war the belligerent, and to a less extent some of the neutral countries, were faced with great shortage of dwellings, with large arrears of repair work to existing buildings, while only a much reduced staff of skilled workmen were available to undertake the greatly increased volume of work. Similar con ditions existed in other industries. It is not surprising therefore that the cost of building rose; and that the extent of the rise was increased by the general rise in the cost of living and the consequent addition to the rates of pay.In view of the fact that such high prices were deemed to be temporary, it was impossible to finance the building of houses to let, even if remunerative rents had been for the moment obtain able, and for a large section of the community they were im practicable. The proportion which could be borrowed on mortgage was reduced in the face of such inflated prices ; consequently, the fortunate section who had benefited by the war industries and who had ready money accumulated could alone afford to buy or build dwellings. The demand for houses for the middle and work ing classes was quite abnormal. The middle classes, the clerks and the skilled well paid artisans, were as much affected by the shortage as the unskilled labourers or the very poor. The return ing soldiers found all the existing dwellings occupied and their demand for homes intensified the need. These conditions consti tuted a quite special housing problem, different not only on account of its magnitude, but also because of the general char acter of the shortage, from the housing problem existing in pre war days, which there is reason to fear may still remain to be dealt with after the special shortage due to the war has been made good.

After the war it was still hardly possible to gauge the extent of the actual shortage of houses in Great Britain, or of the effec tive demand for them which would arise on demobilization. Many estimates of the need were made, varying from 300,00o up to 1,000,000, depending much on the standard that was adopted in regard to the condemning of old houses. Accurate estimates for the decay and demolition of dwellings are difficult to make at any time. Moreover, it was not easy to estimate the number of post war families which would need separate dwellings. After the census of 1921, however, figures were available for the number of separate dwellings and families or units of occupancy, which could fairly be compared with those recorded in the 1911 census. Such comparison affords, perhaps, the best foundation available for comparing the need of dwellings at the census periods and indeed at any intermediate date. The relative figures from the two census returns are as follows : Dwellings and Families.It will be noticed that the number of separate dwellings available for each hundred families fell from 97.6% to 91.9%. On the same standard of accommodation as shown in the 1911 census there should have been 8,529,456 sepa rate dwellings in 1921 showing a relative shortage of In other words 8,5 29,456 separate dwellings would have been required in the 1921 census to show the same relation between the number of separate census family units and the number of separate dwellings as recorded in 1911. It will be realized that separate families for census purposes has a special meaning; and while its character may vary from census to census it does ap pear to have some relation to the units of population requiring separate dwellings. The number of empty dwellings recorded in 1921 on the night of the census is less by 218,833 than the num ber recorded in 1911. This seems to indicate that the intense pressure for housing accommodation known to exist in 1921 had the effect of reducing the number of empty dwellings from 048 to 218,833. From one point of view it may be regarded as surprising that the reduction in empties was not greater; on the other hand, it must be remembered that the empties for census purposes include dwellings temporarily closed while the occupants are absent on holiday or for other purposes. The number of empties in the 1901 census was still greater (448,932), and in view of the smaller number of dwellings then in existence the propor tion of empties would be somewhat higher than the difference in the figures show. It is not possible to estimate with accuracy what figure for empty dwellings on the basis of the census return can be regarded as adequate in normal times to allow for dwell ings from which the occupants are temporarily absent ; to provide for empties during changes of tenancy ; to allow for the reasonable mobility of the workers ; for periods when houses are undergoing drastic repair, or are about to go out of use; as well as those which may be caused locally by definite changes in the distribution of population. Perhaps the figure will lie somewhere between the number shown in the census of 1911 and that shown in the census of 1921. When, moreover, it is realised that the 1911 census re corded 3,129,472 people as living in an overcrowded condition, that is, more than two people to the room, it would seem safer when comparing the conditions with those existing in 1911 to accept the proportion of empties at that period as forming part of those conditions; and an estimate of the need of dwellings in 1921 based on the number required to restore the condition of housing generally as in 1911 can hardly be regarded as other than a moderate standard to take as a measure of the post-war housing problem.

Taking into consideration the number of unoccupied dwellings that there must be at any time, the number of people who own week-end cottages or in other ways occupy more than one dwelling, and the extent of overcrowding still existing, bearing in mind also that the small size of some of the existing dwellings renders them inadequate to provide for families of average size ; many housing reformers would be inclined to set off the number of empties against the limited number of cases where it is desirable for two families to occupy one dwelling, and would like to aim at a con dition which would be shown if the census returns gave the num ber of separate dwellings equal to the number of separate families. It should be realized that neither the standard of the 1911 census, nor the standard of one family one dwelling accurately represents the actual need of new dwellings in order that the people of Great Britain may be properly housed; nor, on the other hand, does it indicate the effective demand for dwellings ; that is, the number which if built would be immediately occupied by people who could afford to pay the rents at which the houses could be provided with the present financial assistance, building prices and rate of interest.

Reference has already been made to the number of people living in an overcrowded condition, based on the standard of two persons per room. This number increased from 3,139,472persons in 1911 to 3,580,274 persons in 1921. The increase of density of room occupation, which shows the pressure on house space in 1921, is not however spread over the whole range of dwellings, but is chiefly found in the one-roomed dwellings. It should be realized that between the census periods the average size of fam ilies recorded for census purposes has fallen, the figures being as follows : Density of Occupation.The following tables indicate the comparison of density of occupation at the time of the two census periods, both in terms of occupants per room and rooms per occupant, from which it will be seen that the reduction in the size of family is reflected in a reduced density except in the case of one roomed dwellings, where the greatest overcrowding is found.

Further interesting comparison is that between the percentage of families at the two census periods occupying dwellings of various sizes. The general move down in size of dwelling per family as the result of the war, and partly perhaps also as the result of the average reduction in the size of the family unit, is apparent. The total of II5% of families occupying dwellings of 1 and 2 rooms and of occupying dwellings of 1 to 3 rooms suggests a considerable population living in very inadequate dwellings.

The above figures taken together, indicating to some extent the degree of overcrowding in existing dwellings, show that even if the number of dwellings were brought up to the 1911 standard, or to the standard of one dwelling one family, it might still be found that there were in existence too many dwellings defective in character or providing inadequate accommodation for the size of the families.

A fairly accurate record of all dwellings erected year by year in England and Wales since the census of 1921 is available, the total to the end of March 1928 being 1,020,123. No such accurate figures are, however, available for the wastage of houses due to demolition on account of old age, to removal to make way for the expansion of the business and industrial quarters in the grow ing towns, or for the making of new roads, railways or other pub lic works. As regards wastage from old age an estimate is some times made based on the assumption that the houses built during the i9th century may be given an average effective life of from eighty to one hundred years. Such an estimate must rest solely on general observation and judgment. Taking it however for what it is worth, the number of additional families which would fall to be provided for eighty years ago would be in round figures 40,000 per annum, and assuming on the average that the number of houses built would bear a fairly close relation to the increase of population, if the average age is taken at from eighty to one hundred years, something like that number of houses should be reaching the limit of their useful life each year. To this figure would need to be added those demolished for other reasons, here again only a conjectural estimate can be made. If that be taken at five thousand houses per annum demolished for all other pur poses than old age, a figure would be reached of forty-five thousand houses per annum needed fully to maintain the desir able supply of housing, in addition to any needed to provide for a growing population.

Increase of Dwellings.

Records of the number of houses built year by year before the war are not available; but the returns as to inhabited houses duly show the net increase in the number of dwellings yearly from 1900 to 1914 as follows : I 900 . . . . 12 2,5 78 1908 . . . . 126,569 190I . . . . 117,146 1909 . . . . 96,251 1902 . . . . 108,034 1910 . . . . 29,532 1903 . . . . 118,681 1911 . . . . 89,7781904 . . . . 115,409 1912 . . 57,039 1905 . . . . 129,842 1913 . . . . 1906 . . . . 101,674 1914 . . . . 67,577 1907 . . . . These figures, which do not include houses built to replace those destroyed but only the net increase in the total number of dwellings assessed, do not suggest that an allowance of rather over 100,00o new dwellings per annum for all purposes is likely to prove an unreasonable one.

Houses and Families.

On the basis of the above estimates, and with a full realization of the numerous factors about which there is considerable uncertainty, it may, nevertheless, be worth while to assess the position in England and Wales at the end of March 1928. An estimate of the probable number of separate families on the census basis for that date gives a figure of 9,208, 500; adding to the number of separate dwellings, shown in the 1921 census, the number built and deducting for wastage of houses for six and three quarter years at the rate of 45,000 per annum given above ; the following figures would be arrived at as an indi cation of the number of dwellings needed at the end of March 1928 (a) to restore the position as in the 1911 census, which may perhaps be regarded as the special war problem, or (b) to pro vide the number of dwellings on the standard of one family one dwelling: Estimate of separate Families as at March 31, 1928 9,208,500 Standard of 191i Census 97.6 dwellings per 100 families: 97.6% of 9,208,500 families=separate dwellings ... . . Separate dwellings recorded in 1921 8,030,000 Built between 1921 and March 31, 1928 1,020,123 Gross total dwellings . . 9,050,123 Less wastage estimated, 61 years at . No. of dwellings estimated at March 31, 1928 Deficiency on 1911 census basis . . dwellings 241,123 To give one family one dwelling: Family units at March 1928 . . . 9,208,500 Dwellings Required to give one family one dwelling standard dwellings 463,127 If this estimate were correct it would indicate that at the end of March 1928 sufficient houses had been built to meet current needs year by year and to contribute 258,333 dwellings towards the war time arrears. Moreover, if it could be assumed that the 215,215 less dwellings recorded as empties as compared with 1911 represented the condition also at March 31, 1928, and that this reduction in empties did not represent houses occupied which ought to have been empty on account of unfitness or other good reason, there would then be shown a deficiency of occupied dwellings as compared with 1911 of only 25,908. Such assump tions would be very unsafe, however, in face of the general evi dence as to the extent of the need still remaining in the spring of 1928.While these figures may be useful as giving a rough estimate of the position, too much reliance must not be placed upon their accuracy owing to the uncertainty about the wastage of old houses and other factors. Nor should the assumption be made that if the deficiency, on the 1911 basis, whatever it may actually be, could be made good at once, there would be an effective de mand for so large a number of dwellings. The extent and dura tion of unemployment existing in Great Britain must be borne in mind; a large number of people have become accustomed to the inconvenience of two families living in one dwelling. The number of new dwellings which these families would be willing to take up at the rentals at which they can be provided, even with the present financial assistance, can only be approximately gauged by the definite demands for new dwellings of which the various local authorities have records.

The need for housing accommodation and the pressure on existing dwellings are affected not only by the rate of increase in the population, but also by the average numbers in the separate families. The tendency which has for some time prevailed for the average number of persons per family to diminish, increases the number of dwellings needed to provide for every thousand of the population. On the other hand, the same tendency to smaller families is likely to reduce the extent of overcrowding in existing dwellings or rooms.

Allowing for the diminishing increase in the population, and making due allowance for the increasing number of dwellings which will annually reach the estimated limiting age of 8o years in the future, it seems probable that the annual need for new dwellings will for long lie in the neighbourhood of ioo,000 per annum, and may prove somewhat less. To this figure something may need to be added for the clearance or improvement of slum areas if not adequately covered by the allowance made for wast age. During the last few years the building industry has been erecting houses at a rate considerably over 200,000 per annum. A sudden drop from such a figure to an output of 1 oo,000 would be serious for the industry. While it is desirable that the deficiency in dwellings should be made good as rapidly as possible, time should be allowed for a gradual slowing down to the normal figure so that such sudden drop in production may be avoided.

The next census return of 1931 will show how nearly the fore casts are confirmed by the facts and should enable a much closer estimate of the then remaining problems to be made.

While no accurate estimate could be made of the shortage of houses with which Britain would be faced at the end of the World War, the fact that a serious problem would arise had been foreseen ; and it was realized that the resources of the country would be severely taxed to make good the deficiency. In the same way, though it was impossible to forecast the extent to which building prices and rates of interest would rise, it was evident that, under the conditions likely to prevail at the close of the war, it would not be possible to build small dwellings to let on an economic basis, and that on every such house erected until condi tions again reached a level of pre-war stability, a loss must be faced. Unless that loss could be made good by public funds it was clear that no houses would be built to let.

The working of the Rent and Interest Restriction Act, neces sary to prevent a general increase in the rents of existing dwell ings, undoubtedly tended in some cases to increase the difficulty of providing new houses. Several committees appointed by the President of the Local Government Board and the Minister of Reconstruction made a study of the problem, and of the alter native methods for dealing with it. Reference may be made to the following published reports dealing with various aspects of the matter : Memorandum by the Advisory Housing Panel of the Ministry of Reconstruction. Presented October 1917. C. 8. 9087. Published 1918.

Interim and final reports of the Women's Housing Sub. Cd. 9166. Committee Ministry of Reconstruction, 1918-19.

Report of the Housing (Building Construction) Committee C. 9166 (known as the Tudor Walters Committee), 1918.

The method adopted and embodied in the Housing Act of 1919 imposed upon the local authorities the duty of preparing housing schemes for their areas providing for the building, as soon as possible, of the number of houses needed to house the working classes in their districts. Each local authority was required to make a survey of its needs and report the result to the Local Government Board, soon to become the Ministry of Health. To meet the annual loss, i.e., the difference between the net revenue from the rents which could be charged for the houses, and the outgoings for interest, repairs, sinking fund, etc., the Government undertook to bear on behalf of each local authority during the period of the loan, the annual deficiency resulting from approved expenditure in so far as it should exceed the annual proceeds of a local penny rate, which was to represent the contribution of the local authority towards the loss.

Included in the scheme could be improvement or slum clear ance schemes made under Parts I. and II. of the Housing Acts, and the loss incurred in these was treated as part of the scheme for the purpose of assessing the Government's contribution.

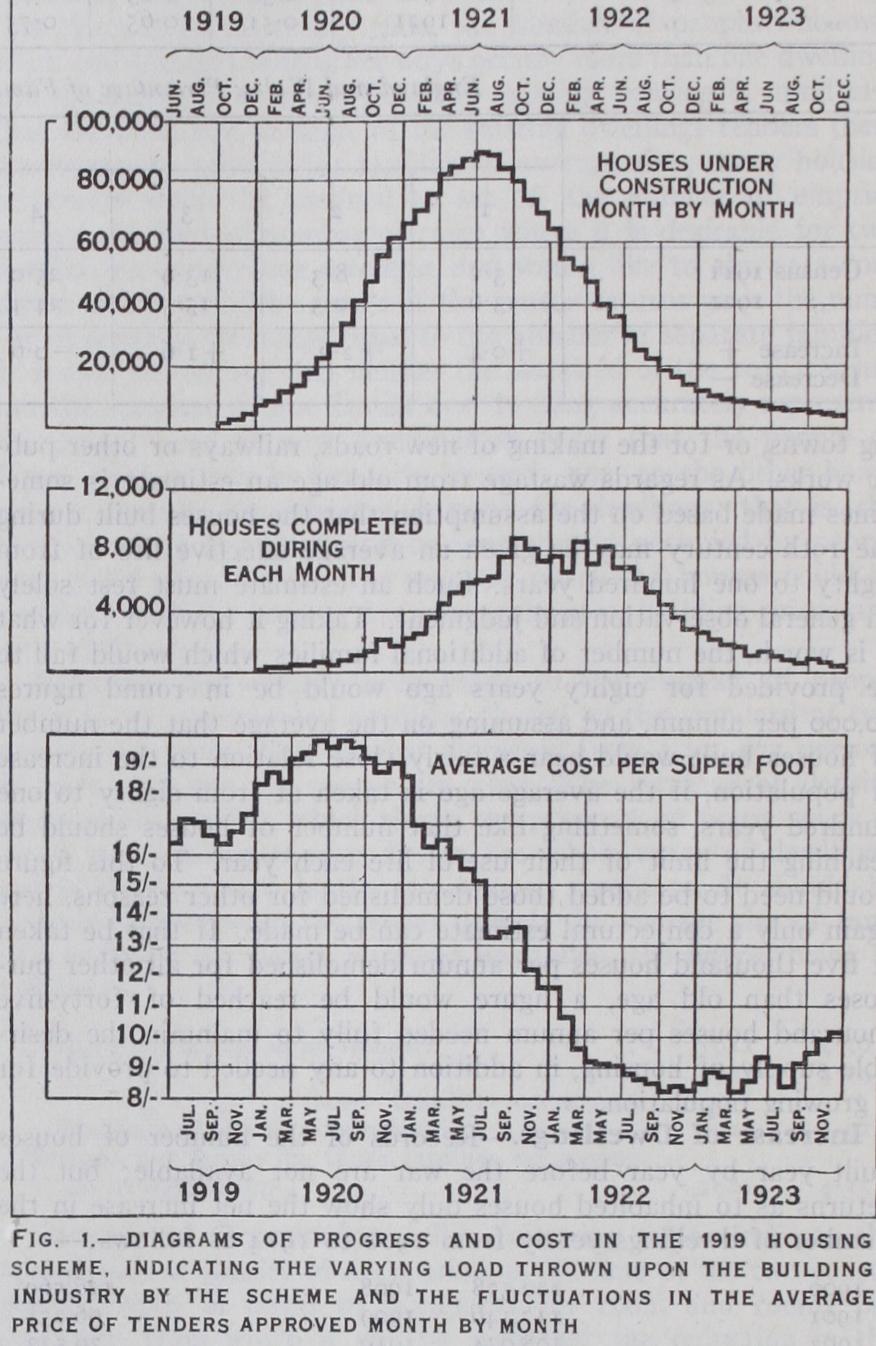

Financial assistance was given on a comparable scale though in different form to public utility societies. In a later act, to en courage private enterprise, a subsidy in the form of a lump sum grant per house was offered to private persons building houses within prescribed limits of size and specification of character. As a result of this scheme about 570,000 houses were erected by some 1,274 municipal authorities, 4,500 by public utility societies, and 40,000 by private persons or builders. The progress of the housing scheme is summarized in the following diagrams indi cating the fluctuation in production and in cost. (See fig. I.) In regard to the contracts placed by municipal authorities, progress during 1919 was slow. Prices tendered for houses gradually rose, concurrently with the increased demands upon the industry, and with the general rise in the cost of living, rates of wages and prices of building materials. The peak of prices was reached in the summer of 1920 from which time a general decline com menced. This was mainly due to the check which high prices produced in all classes of building other than domestic. Men and materials were liberated for housing work so rapidly that in spite of the increasing numbers put in hand during the autumn of 1920 and in 1921, prices continued to fall. The exercise of greater caution in loading the industry, and stricter control of the prices approved, helped materially to bring about the down ward tendency during the autumn of 192o.

In the spring of 1921 conditions of financial stress brought about a change of policy; the expansion of the housing scheme was checked, and in the summer of 1921 the scheme was terminated by a decision to limit the number of houses to be erected under it to a maximum of about 175,00o. This curtailment and ulti mate stoppage of the scheme intensified the fall in prices which had previously set in, and which already affected many other national products. The fall in building prices ultimately stimu lated the production of houses for sale, and other branches of the building industry; but as regards the smaller dwellings for the working classes, few new houses were put in hand to take the place of the subsidized contracts under the previous housing scheme, which were rapidly being completed during 1922. Towards the end of that year the housing position was again be coming acute; the number of houses to which the first scheme had been limited, did not suffice to keep pace with the annual growth of the housing need since the end of the war, and had done nothing to meet the accumulated arrears of the war period. Even at the comparatively low prices then available for the small number of houses being put in hand, it was evident that without some form of financial assistance dwellings for the working classes could not be erected to let. In the spring of 1923 a new act was promoted by the Minister of Health under which a subsidy was again offered, but on quite different condi tions.

Under the 1919 housing scheme, while the local authorities were made responsible for building houses subject to the ap proval of the Local Government Board, the contribution towards the loss on the dwellings which they had to make was limited to the proceeds, year by year, of a penny rate ; and the Government had undertaken to make good the remainder of the loss by an annual subsidy to the local authorities which was thus unlimited. The amount of the penny rate representing in most cases a very small proportion of the loss, the position was soon reached that the whole of the further loss on the schemes being dealt with fell upon the Government, who had only limited means of con trolling the expenditure under contracts made between the local authorities and the builders. Such a position was administratively one of great difficulty; on the one hand it gave little encourage ment to economy on the part of the local authorities ; on the other hand it sometimes promoted the cutting down of the standard of building as a means of reducing the price and so securing the approval of the Government to contracts very ad vantageous to the local authorities. In the Housing Act of 1923 the position was reversed. The Government undertook to give a definite and limited contribution of £6 per annum per house for a period of twenty years towards the loss which the local authori ties might incur in building houses, the latter taking all risk of further loss. Moreover, to encourage private enterprise, the local authorities were authorized, under schemes to be generally approved by the Minister of Health, to give assistance to build ers or others wishing to erect houses suitable for the working classes. This assistance could either take the form of passing on to the builder the L6 per year for twenty years, which they would receive from the Government, or the local authorities could, on the security of this payment, raise the equivalent sum, about £75, and give it as a capital grant to the builder. They were further empowered to increase the amount of the grant at the expense of the local rates. Many local authorities did in fact pay lump sum grants of £ 1 oo or even more per house.

Provision was also made in this act for subsidizing in a new form slum clearance schemes. In addition to approving loans, the minister was authorized to make grants towards the ex penses incurred by local authorities in carrying out improvement schemes, and the consequent re-housing work, under Parts I. and II. of the Housing Acts. The amount of the grant which was to take the form of a fixed annual contribution was to be settled in each case by consultation with the local authority but was not to exceed 5o per cent of the estimated average annual loss likely to be incurred in carrying out the scheme. While contributions have varied, the full so per cent has usually been paid in respect of approved schemes.

Additional powers were also given to local authorities to assist private enterprise by way of loans to builders of houses not exceeding £1,500 in value. The Small Dwellings Acquisition Act was amended so as to facilitate loans to owner occupiers for houses not exceeding £1,200 in value. Guarantees to building societies were also authorized so that local authorities could facilitate their operations if they so desired.

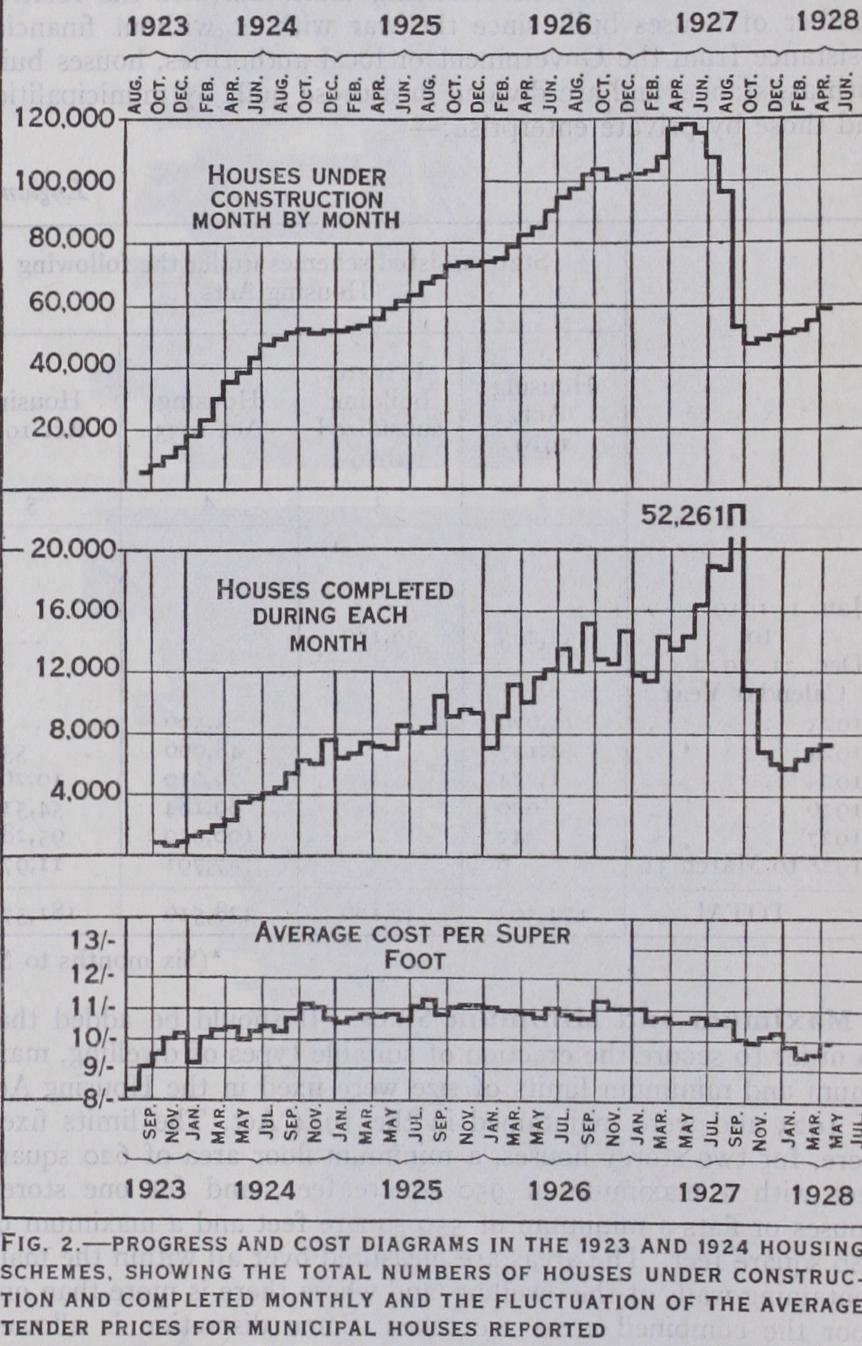

The scheme began to produce considerable effect in the autumn of 1923 by which time about io,000 houses, qualified to receive assistance under the new scheme, were being constructed; this number rose to about 50,000 in the summer of 1924. The new Labour Government which was then in power considering that the act had not adequately stimulated the building of dwell ings to be let to the poorer classes, introduced a further housing act known as the Housing (Financial Provisions) Act 1924. This act left the provisions of the 1923 scheme untouched except as regards one or two minor details of the conditions. Its operation was indeed continued for a period of 15 years, subject to periodic revision as to the amount of the subsidy. In addition to the terms of the former act however it created a new form of financial assistance in the shape of an increased subsidy given for houses built under covenants that they were not to be sold, but to be let under special conditions. The most important was that so long as the annual charge on the rates did not exceed £4 1os. per house, houses should be let at rents not exceeding the rent of similar pre-war houses for the time being prevailing in the district. Since 1924 both these schemes have been running concurrently. The 1923 scheme, with its provision for a lump sum grant and its freedom to sell, has naturally proved the more attractive to private enterprise, while the 1924 scheme which authorized a subsidy of L9 per year for forty years in urban areas and £12.105. for agricultural areas for the same period, has proved more attractive to local authorities. They were in a position to comply with the conditions as to letting; and could limit the rents to the required amount by meeting any additional loss out of the local rates. Under the terms of the act they are required to do this up to, but not exceeding, an amount of Q4.1 os. per annum. After this, if a further loss would be entailed, owing to the relation of local costs to prevalent rents, these rents may be increased sufficiently to keep down the contribution from the local rates to the figure of £4.1 os. per annum. The numbers of houses built under these two schemes grew rapidly until the end of Sept. 1927, when the first revision of the subsidy took effect. All houses completed of ter that date were eligible only for a re duced subsidy of f4 per house for twenty years under the 1923 Act, and, under the 1924 Act, f 7. I os. per house for forty years urban areas and f 11 2s. 6d. in agricultural areas. The general progress of the 1923-24 housing schemes is shown by diagrams which may be compared with those for the 1919 scheme. (See fig. 2.) Previous to the outbreak of war in 1914 the actual contribu tion to the number of houses erected year by year made by local authorities was very small. The vast majority of houses were erected by private enterprise without any public assistance. Volun tary agencies, such as building societies, co-operative and co partnership societies of various types, were contributing an in creasing number of dwellings and were particularly influencing the type of houses and the standard of lay out and amenity. But apart from the building societies mainly financed by private enter prise, the volume of building by all these agencies was relatively small. The war conditions had the effect of bringing private enter prise building practically to a standstill, and not until some years had elapsed were conditions such that private enterprise gradually resumed its activities. The following table indicates the relative number of houses built since the war with or without financial assistance from the Government or local authorities, houses built with assistance, and are divided into those built by municipalities and those by private enterprise : the Minister to deal with special cases.

In regard to the subsidy for private persons under the 1923 and 1924 Acts, local authorities have been given considerable freedom to adapt schemes to local circumstances; but they have been encouraged to include conditions calculated to check the misuse of the subsidy, such as, the control of the further sale of dwellings within a period of years, or the limiting of the right to alter or extend the building within a like period, and the fix ing of maximum selling prices. This latter was subsequently made an absolute condition for earning the grant.

Slum Clearance.

Apart from the provision of additional new dwellings, a commencement has been made with the clearing of unhealthy areas. In spite of the priority given to the erection of new dwellings to increase the total supply, up to the end of January 1928 the following progress had been made.No. of houses (including shops or other buildings) in schemes confirmed . 14,135 No. actually acquired . . . . . . . . 9,28o No. demolished . . . . . . . 5,164 Total number of persons required to be rehoused in con nection with schemes confirmed . 68,427 No. of dwellings for which loans have been sanctioned . 8,377 No. completed . . 5,887 Some idea of the volume of work undertaken by local authori ties in connection with the inspection of dwellings, the repair of those found defective, and their closing or demolition, may be gathered from the following particulars given in the Annual Re port of the Ministry of Health for the year 1926-27: Maximum and Minimum Sizes.It should be added that in order to secure the erection of suitable types of dwelling, max imum and minimum limits of size were fixed in the Housing Act of 1923 and were maintained in the 1924 Act. The limits fixed were, for two storey houses, a minimum floor area of 62o square feet with a maximum of 95o square feet; and for one storey houses or flats a minimum of 55o square feet and a maximum of 88o square feet. The areas are measured over all within the main containing walls of the dwelling, and where there is more than one floor the combined areas are taken. Some discretion is allowed to the Minister in special circumstances to permit houses 5o feet smaller than the minimum figures given. In the 1923 Act, houses were required to be provided with a bath, and in the 1924 Act the words were added "in a bathroom." Here again some discre tion is allowed to the Minister to dispense with this requirement in special cases, as for example in rural areas where adequate water supply and drainage facilities may not exist. Under all the schemes a requirement that houses shall be built at a density not exceeding twelve to the acre in urban areas and eight to the acre in rural has been generally operative, discretion being left to During the year under review reports by Medical Officers of Health were received for the year 1925.

In 1,677 districts for which returns were tabulated, 428,625 houses were inspected under the Housing (Inspection of District) Regulations, and the total number of houses inspected, including inspections under the Public Health Acts, was 1,114,504. Defects in houses were remedied without the service of formal notices. Notices under section 28 of the Housing, Town Planning, etc. Act, 1919, or section 3 of the Housing Act, 1925, were served in respect of 24,369 houses, and of these houses 18,961 were rendered fit by their owners, and 785 by the Local Authorities, while in 463 cases the owners gave notice of their intention to close the houses. Notices were served under the Public Health Acts in respect of 278,894 houses; in 225,058 of the houses the defects were remedied by the owners, and in 4,285 by the Local Authorities.

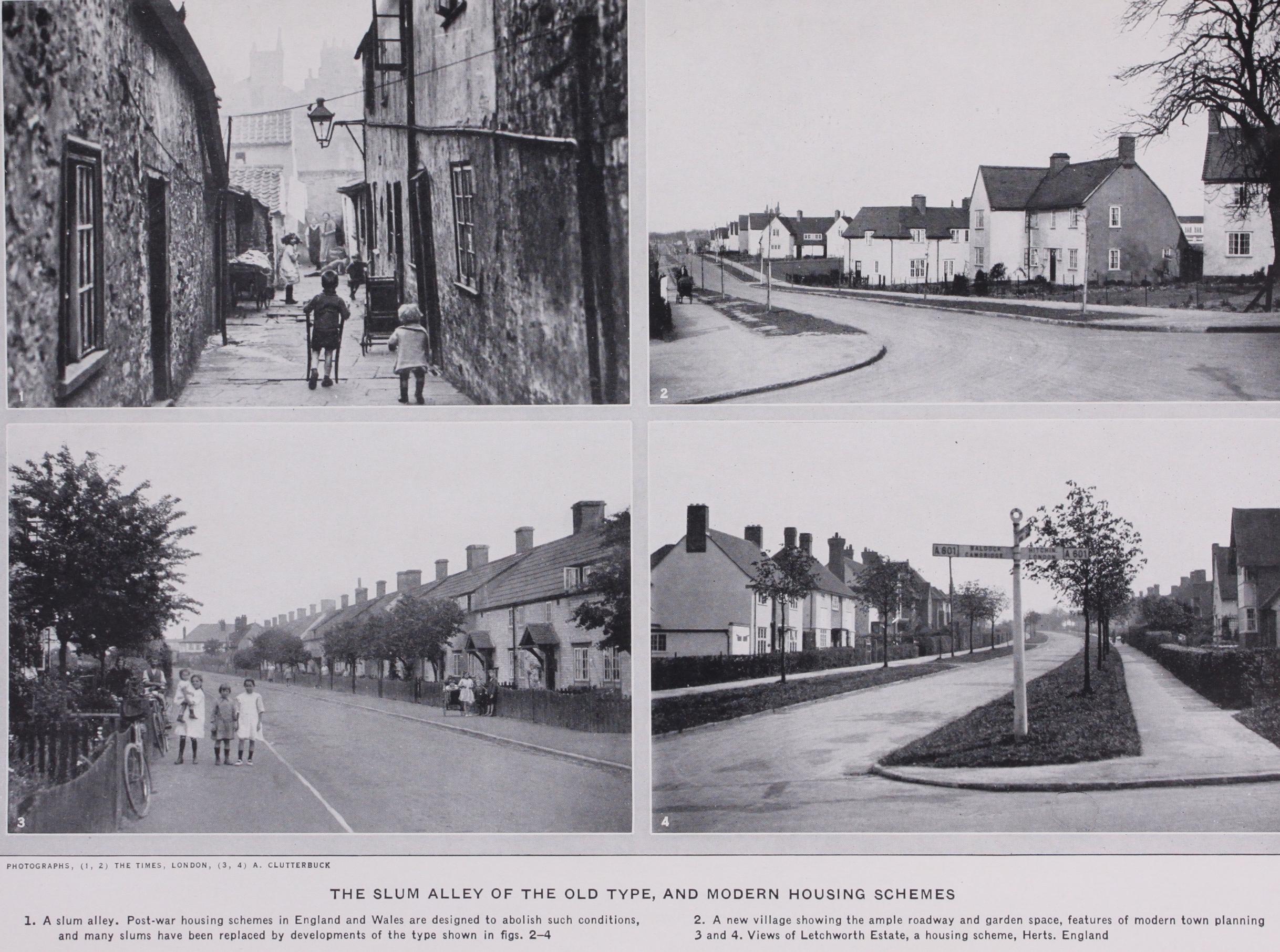

The figures as to Closing and Demolition Orders were as follow:- Representations made with a view to Closing Orders . . 3,141 Dwelling houses in respect of which Closing Orders were made . 2,287 Closing Orders determined after houses were made fit . 443 Dwelling houses in respect of which Demolition Orders were made 549 Dwelling houses demolished in pursuance of Demolition Orders . 678 IV. STANDARDS OF DEVELOPMENT AND ACCOMMODATION The general limitation of the density of building to i 2 houses to the acre in urban and 8 in rural areas has proved perhaps the most valuable as it has been the most characteristic feature of if any, extra cost, the open type of development having allowed economies to be effected in the amount and character of the road works which must have balanced the small extra cost of the additional land.

The gain that can be made by crowding dwellings on land is in any case small; and must be regarded as a very inadequate offset to the great reduction in open space and amenity which results. Where, as in the assisted housing schemes, the average cost of land has been little in excess of £ 20o per acre, and full opportunity has been afforded to take advantage of less costly types of road appropriate for open development, the possible money gain from over-crowding dwellings practically vanishes, and the advantages of low density become overwhelming.

Economy of Spacious Planning.

The diagrams illustrating the two methods of development and the relative cost per dwell ing show how the small saving in original land cost which can be made by adopting high density, is soon expended in the extra post-war housing. It has greatly added to the economic ability of the tenants to pay rent by providing each with a valuable plot of garden ground. It has secured ample air space and sunlight for all the dwellings and increased the opportunities for healthy living. It has introduced into housing a new standard of amenity, the garden space and open layout of the sites having enhanced the attractiveness of well designed schemes of houses, and given opportunities for screening in the future with foliage those with less pleasing buildings. (See fig. 4.) This great improvement has moreover been secured at little, road cost which that increased density of dwellings involves. Much road work cost is expended at every street junction which affords no building frontage, and the greater the density the greater the proportion of such wasted works. Lighter roads may also be used with the type of planning which can be adopted with low density; moreover, with open development the placing of the roads and their exact directions can be chosen to suit the ground, and to reduce excavation and filling, or the deep digging of drains, all of which leads to economy in cost. (See fig. 4.) The average standard of accommodation' and size of dwelling adopted in the 1919 housing scheme was influenced by the fact that during the war the building of houses for the well paid arti sans had ceased as completely as the building of smaller houses for the less well paid labourers. Consequently both the Govern ment and the municipalities felt a responsibility to provide houses to meet all sections of the working classes and to interpret that classification in a liberal manner. Owing in the first instance to the rapid rise in building costs, and Iater to the belief that private enterprise could again take up the supply of the larger types of dwelling, the average accommodation and size was gradually re duced. In the first years the majority of houses built were parlour houses (known as B type) but as time passed the pro portions changed and during 1927 the great majority were non parlour houses (A type). Compare figs. 5 and 6.An indication of the extent of reduction in actual size of the two types may be gained from the following representing the average sizes in square feet of municipal houses being approved in the last month of each of the following years : In the A type house part of the reduction in the average size in 1927 is due probably to an increased number of two bedroom FIG. 6.-PLANS INDICATING THE REDUCED SIZES GENERALLY ADOPTED Fig. 6.-PLANS INDICATING THE REDUCED SIZES GENERALLY ADOPTED FOR MUNICIPAL HOUSES IN 1927-1928 houses being included as compared with the earlier periods. In both types moreover the reduction in average area has been in no small degree due to experience and skill in planning to give the required accommodation with the least waste of space, and it does not represent an equal reduction in the size of the rooms.

It is sometimes overlooked that the standard of room area and accommodation adopted in the 1919 housing scheme was not a post war standard due to the enthusiasm for building homes for returning soldiers. It was in fact a pre-war standard, laid down by two committees appointed by the Board of Agriculture and Fisheries, that on Buildings for Small Holdings which reported in 1913 (Cd. 6708) and the Advisory Committee on Rural Cot tages which reported in 1914. The standard. published in those reports was adopted in the Report of the Tudor Walters Corn mittee, and is as shown below.

V. COST AND RENT The cost of building houses varies much from place to place as well as from time to time, and it is affected by the design and size of the individual cottages. Comparisons of cost can therefore usefully be given only in the form of averages, and based on a common type of agreed size. Throughout the various assisted housing schemes since the World War, records of the size and cost of houses, taken from monthly returns sent by the local authorities to the Ministry of Health have been kept, and have been reduced to a common standard of a price per square foot. The general trend of prices for municipal building is therefore ac curately represented by the diagrams based on such monthly figures and showing the average of the tender prices approved month by month, or in the limited number of cases where houses were built by cost contracts, or by direct labour, the approved estimates of cost. (See figs. i and 2.) When seeking to compare prices with those prevalent before the war, the difficulty arises that no similar average prices were then available. It is possible for those experienced in building in differ ent parts of the country to fix a range of prices commonly found in pre-war days for cottage building; but no data exist which would enable the average to be accurately placed within that range. Consequently in comparing the cost of providing a dwell ing in the years immediately preceding the war with the cost at the commencement of 1928, it may be safer to take two figures in both cases, giving the range of usual high and low limits of cost for each of the important items.

The normal three bedroom non parlour cottage, if compactly planned and providing rooms of the standard of accommodation generally recognized as a desirable minimum, would contain on the two floors measured over all within the containing walls about Boo square feet. In pre-war times usually cubic feet would have been taken; the cubic measure for a certain area varies con siderably according to the design of the cottage; but 9,200 cubic feet would be a reasonable figure to take for comparison in this case. For cottages of approximately equivalent character to those erected in post-war housing schemes, though frequently containing no separate bathroom, the range of cost per cubic foot pre-war would be from 4d. to 8d. A figure as low as 4d. was becoming rare, and a figure as high as 8d. was also unusual in carefully managed schemes. It is impossible to say where the average of all working class dwellings erected would be; perhaps 54d. per cubic foot may be taken as a probable average. 9,200 cubic feet at this figure would equal £210 16s. 8d. or 5s. 31d. per square foot ; and, allowing something for the difference in amenity and equip ment, 5s. 6d. per square foot is probably not an unfair average figure to take for pre-war houses for the purpose of comparison with the post-war average figures given above.

As regards land, no average figure can be given, but on the basis of 12 houses to the acre adopted generally for post-war housing schemes and for much of the more progressive work pre-war, the following represents the cost of land at different prices per acre, commonly paid.

£ioo per acre equals per house .. . £ 8 6 8d.

200

16 13 4d ,, 35 6 8d.

How Costs Have Risen.

The cost of road making is another item which varies considerably and for which average figures do not exist. A range of from £20 to £35 pre-war, and £35 to f5o in 1928 would probably cover the majority of cases. On this basis it is possible to set out the probable range of costs for the two periods somewhat as follows : No doubt figures higher and lower could be found in both periods but the above probably represent the ranges of cost within which the majority of dwellings would fall which were built in the year before the war or were being built in the period 1927-28.The economic rent of dwellings depends however not only on the total capital cost of providing the buildings, land, roads, drains, etc. ; but also on the rate of interest and sinking fund ruling at the period ; and on the cost of repairs. To give a general idea of how these different factors affect the weekly rental, it is simpler to take the all-in cost of the cottage and to give examples in round figures of cottages costing £200, £300, £400 and f Soo, which will cover pre-war and present costs. As the cost of repairs will vary much more nearly with the cost of building than with any factor affecting the rate of interest, it is best to take the repairs as a percentage of the cost. Allowing 12% as a reasonable amount to cover repairs, insurance and other similar items, the following