Hungary

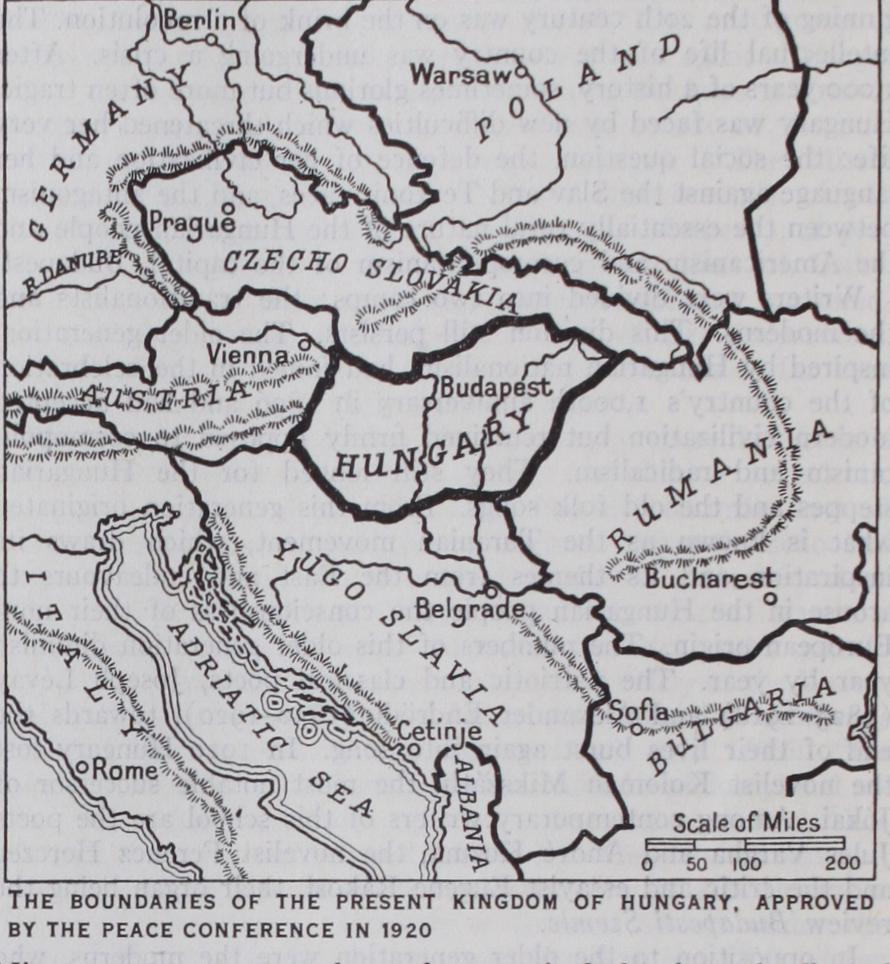

HUNGARY, one of the succession states of the old Austro Hungarian empire, is a landlocked country in central Europe lying between the Alps and the Carpathians and including parts of the two great tectonic basins of the middle Danube. Area, sq.m.

Physical Structure.

Broadly considered the physical struc ture is simple. The structural backbone is formed by a spur of the central and limestone zones of the Alps, which forms the Hungarian Mittelgebirg. Commencing in the Bakony forest (2,34o ft.), between the river Raab and Lake Balaton it trends from south-west to north-east, being continued by the detached ranges of Vertes (1,575 ft.) and Pilis (2,476 ft.). The stratified formations are quite varied ranging from Permian to Recent and are associated with basalt, andesite and other volcanic rocks, which increase in proportion towards the Danube. This group of highlands separates the Little Hungarian plain (Kis-Alfold) to the north-west from the downlands of the Drava-Danube angle to the south-east. The former, of which only that part on the right of the Danube now belonging to Hungary will be con sidered, is drained by the lower Raab and its tributaries and floored by Pliocene strata heavily overlaid by Recent deposits, coarse river gravels, sands and alluvium with patches of loess. Except where swampy as in the region of the Little Schutt island of the Danube and the Hansag marshes this is a rich wheat and sugar-beet district passing gradually east, west and south through rolling downs to forested hills, where occasional stores of lignite and iron-ore supply the fundamentals of manufacture.South and east of Lake Balaton (q.v.) the true downland of Transdanubia occurs. Here, too, intensive agriculture is favoured by vast deposits of loess and loam, deeply seamed by parallel north-west to south-east streams, whose water ultimately reaches the Danube directly or by way of the Drava and the SiO. Rising as a mountainous island from this undulating territory is the massif of the Mecsek hills where outcrops of numerous post Carboniferous formations Triassic and Jurassic limestones com bine with granites, diorites and other igneous rocks to diversify the landscape while on the eastern flank of the hills coal supplies add to the number and character of its human activities. Occa sional patches of alkaline soil along the river courses suggest the conditions so common east of the Danube. This river forms the northern frontier from just below Bratislava to the confluence with the Ipel, a left-bank tributary. A few miles below, at Visegrad, it turns around the Pilis heights and takes its south ward course. East of the river lies the Great Hungarian plain (Nagy-Alfold) but its southern third, i.e., the Baeka, between the Danube and Tisa, and the Banat, east of the Tisa, is no longer under Hungarian rule.

Despite the uniformity of relief great variations exist in soil conditions, and therefore in agricultural pursuits, on this plain. For the most part alluvium and alluvial loess are the principal soils but near its northern edge Tertiary deposits, mainly of Miocene age, appear at the surface particularly along the line of the northern highlands, where they are associated with coarse alluvial fans and eruptive rocks, the latter dating from the volcanic activity accompanying the fractures and subsidence which originated the basin. Alternations of marine and lacustrine conditions during Miocene and Pliocene time built up thick deposits of debris from the surrounding highlands, coarsely graded from the margins to the centre of the basin, and these were in part covered by wind-borne material, loess and sand, in which subsequent drainage has developed broad alluvial-floored channels. Drainage, the work of the Danube, Tisa and their tributaries, is indecisive and is supplemented by an extensive system of canals, dikes and river-regularization, yet despite these efforts large areas are still liable to floods and to the formation of alkaline soils. The northern highlands continue in broken form the line of the Mittelgebirges, with the contrast that they are richer in eruptive rocks. From the Danube eastward to the Zagyva rise the Borzsony (3,08o ft.), and the Cserhat (2,13o ft.), groups, between the Zagyva and the Hernad, the Matra ft.), mainly trachytes, and the Biikk, a complex of Carboniferous shales, Jurassic limestones and volcanics, while beyond the Hernad to the frontier stretches part of the Eperjes-Tokaj volcanic range, renowned for the fertility of its soil and the quality of its vine yards.

The climate of Hungary is transitional between oceanic and continental. The three great climatic regions of Europe, the West European, East European and Mediterranean, here struggle for supremacy. The mean annual temperature ranges from 48° F in the north to 52° F in the south and in general the country shows a positive isanomalous temperature. The annual range of tem perature varies from 40-47° F, but may in exposed districts of the Nagy-Alfold greatly exceed the higher figure. The distribu tion of precipitation over the land shows a decrease in amount eastwards. The greatest quantity is received on the western slopes of the Bakony forest where from 30-35 in. fall per annum; the driest region is the middle Tisa with less than 15 in. in dry years, though sheltered regions such as the south-east slopes of the Hegyalja are very dry. Most rain falls in May and June (June, 13% of year's total) with a tendency towards a secondary maxi mum, caused by Mediterranean influences, in late autumn (Octo ber, io% of year's total) particularly in the Drava-Danube angle. On the Nagy-Alf old the rainfall occurs mainly during occasional storms but elsewhere it is more evenly distributed. The high summer temperatures while excellent for wheat and maize are dangerous when rainfall is below the average, and when this is associated with heavy winds disastrous sandstorms and crop destruction follow. One of the characteristics of the climate of most value to the people is the long autumn whereby the ripen ing of delicate crops, e.g., vine and other fruits, is assured. The critical feature of the climate from the agricultural point of view is the uncertainty of sufficient rainfall; history shows a series of droughts and famines owing to the small margin of safety.

The response of natural vegetation to these climatic conditions is clear where original examples unaltered by man are found. The characteristic covering of the Transdanubian lands is deciduous woodland, oak, beech, lime and chestnut, but these disappear rapidly towards the Nagy-Alfold where steppe conditions prevail. These are probably of human production for along the stream courses small "gallery" woods of alder-willow association are common.

Population and Settlement.

The population of Hungary (1930, estimated at 8,688,319; area, 35,911 sq.m.) is predomi nantly of Magyar speech and origin, the estimated 193o per centages according to speech being Magyar 92.1, German Slovak 1•2, others 1•2. According to religious belief 64.9% are Roman Catholics, 2.3% Greek Catholics, 27% Protestants and 5.1% Jews. The German minority is not concentrated but exists as enclaves principally in Budapest, along the western frontier and in the Bakony forest and the Danube-Drava angle. The Slovaks, too, are distributed but in small groups in and near the capital and in the county of Bekes of the south-eastern frontier zone. The Jewish element, a powerful economic influence, is urban and representatives are found in most of the large towns, especially in the capital.The Danube in its north-south course from Visegrad to the Yugoslav frontier divides Hungary into two contrasted regions. West of the river in Transdanubia, the old Pannonia, a tradition of culture, relatively free from interruption, is carried back to pre-Roman days and is based upon settled conditions and agri cultural prosperity. Further, conditions of climate are here more favourable than on the Nagy-Alfold where natural difficulties and periodic invasions have disturbed settlement and retarded the development of intensive agriculture. The capital, too, with its eyes on the West and susceptible to the same cultural influences that have shaped Transdanubia, is less representative of life on the great plain where habits, customs and costumes retain much of their primitive stamp. The difference of physical conditions and history are reflected in the land utilization, the forms of set tlement and house-types. Thus Transdanubia falls into three regions, the Kisal f old where on a denuded plain about 350-425 ft. above sea-level the population carries on an advanced and balanced agriculture based on wheat, rye, fodder plants and cattle-rearing, the central highland belt including the Lake Balaton district where forestry, fishing, mining and tourist traffic supplements a similar intensive agriculture and the Danube Drava angle, which resembles the second region but has more advanced mining and agriculture.

On these three regions the unit of settlement is the village, either the Hau f endor f or the Runddorf on the plains and the Strassen dorf along the valleys of the highlands. On the Nagy-Alfold two great regions are recognizable, the Danube-Tisa interstream area, with its lines of dunes and marshy hollows, often floored with alkaline soil, and scanty drainage and, at a lower level, the true steppe east of the Tisa with its vast stretches of cereal land and cattle pastures. On these regions are the great "farmer towns" of Hungary, enormous agglomerations of people, mainly agricultural, grouped in settlements, the results of grouping for defence, that are but slowly developing the characteristics of true urban centres. Such are Debrecen Kecskemet, Czegled and Szeged, where many of the population live, while practising an extensive agriculture or semi-nomadic cattle-herding miles distant on the plain. In recent times small isolated houses (single tanyas) and self-contained villages (grouped tanyas) have com menced to rise in the vast spaces between these towns and to develop from seasonal to permanent homes. In these isolated districts tradition dies hard and a sturdy peasantry treasures a conservatism of outlook that, fostered by difficulties of communi cation, resists the impact of modern ideas. Both regions of the Nagy-Alfold sweep up to the rich vine-clad and forested slopes of the northern highlands where mining and tourists enlarge the human interests.

Agriculture.

Agriculture is the basis of Hungarian life. Of the entire population of Hungary in 1926 about 55.8% were engaged in agricultural work as compared with 30.1% in industrial and commercial activities. In the five years which preceded the World War, Hungary's agricultural production showed a gradual but constant development in consequence of the draining of flooded areas and the extended use of agricultural machines and artificial manures. This development was arrested by the war, the succeeding revolutions, the occupation of the country by foreign Powers and by the viovisions of the Peace Treaty. Owing to the scarcity of labour, draught animals and manure, the arable land, amounting to 5,600,000 hectares, could not be properly cultivated, and a considerable decrease of production resulted. The down ward tendency reached its lowest level in the years 1919-20; from that time progress, at first slow and later quicker, was visible, some crops showing a yield which compared favourably with those of pre-war years.Of the total area 63.6% is arable, 17.9% meadowland and rough pasture and 11.8% forest. Prior to 1918 large estates were very common but since that date they have gradually declined in relative proportion as the result of agrarian reform measures, not always with advantageous results upon the yields of crops. Climatic catastrophes take heavy toll of crops and cause great fluctuations in the annual yields, e.g., in 1913, 28% of the sown area in the Tisa counties failed through storm, flood and drought. Generally, yields have declined since 1913 in response to the acute stress accompanying readjustment. The greatest acreage is devoted to wheat (1926--3,757,337 ac.) which is followed by maize (1926-2,668,236 ac.), rye (1926-1,748,010 ac.), barley (1926-1,063,869 ac.) and potatoes (1926-627,322 ac.). Wheat reaches its greatest intensity along the middle Tisa and in the Koros region but is well-distributed except in the highlands and sandy areas of the Nyirseg and Danube-Tisa plateaux where its place is taken by rye, a crop also prominent in Transdanubia. Maize, too, is general with concentrations in the drier regions of high summer temperature, e.g., east of the Tisa and along the fertile borderland of the southern frontier. Potatoes and root crops are closely associated with the intensive farming of Trans danubia and to a lesser extent with the sandy areas.

The following table shows the yield of seven principal crops:— The values in millions of pounds sterling of the seven principal crops mentioned above amounted in 1920 to 14.2, 1921 to 22.7, 1922 to 29.4, 1923 to 33.o, 1924 to 51.6, 1925 to 56.8, 1926 to 44.6, and in 1927 to 57.2. Before the war the same seven crops pro duced in the territory of present Hungary (calculated on the basis of the prices of 1913) had a value of 48,400,000. The total value of the agricultural products is now about £So,coo,000.

The cultivation of vines, fruit and garden produce is impor tant. More than half of the vineyard area is in the drift sand districts which are immune from phylloxera and the vine acts as a binder. Elsewhere it dominates the volcanic southern slopes of the Mittelgebirges overlooking Lake Balaton and those of the Hegyalja from which comes the famous Tokaj wine. Fruit culture is prominent in Transdanubia and the inter-stream land of the Danube-Tisa, notably at Kecskemet, Czegled and Felegyhaza, (apricots, apples), in the Hernad valley (cherries) and the environs of Szeged. The growth of early vegetables for export, fresh or preserved, increases rapidly near the large towns and certain districts specialize in particular products, e.g., melons in the county of Heves, peppers at Szeged and onions at Make). Commercial plants have always been to the fore and include tobacco on the Nyirseg plateau, hemp on the drier regions of the Nagy-Alf old, flax in the moister districts of Transdanubia, sugar beet (1926-159,901 ac.) in small quantities evenly distributed over the country and hops in the Hernad valley.

The breeding of stock follows cereal production as the most important aspect of Hungarian agriculture. In 1927 the numbers of animals were as follows:—Cattle, 1,80J438; sheep, 1,610,716; pigs, 2,386,664; horses, 903,326. Cattle-rearing exists in two stages of development. On the Nagy-Alf old it is passing from extensive to intensive conditions. Alkaline and other soils un suited to cereals, such as the Bugacs puszta near Kecskemet and the vast Hortobagy steppe west of Debrecen, still pasture enor mous numbers of sheep, cattle and horses tended by semi-nomadic herdsmen, many of the cattle being the descendants of the native white longhorned breed, but west of the Danube rearing is intensive, associated with stall-feeding and heavy production of fodder plants and large numbers of Simmenthal cattle appear. Here the organized development of dairy-farming is most ad vanced though modern methods are spreading fast over the whole country. The national love of horses and their general use in daily life cause them to be bred in many centres. Pigs, chiefly of the Mangalica lard-producing breed, are most commonly found on the smaller properties, e.g., in Western Hungary, near the towns as at Budapest and in the maize region of the Koros-Maros. Sheep are bred for milk and coarse wool to supply local needs and are found in greatest numbers on the slopes of the Mittel gebirges and northern highlands and the natural pastures of the Nagy-Alf old. Other stock interests include goats on small hold ings, poultry in the wheat districts of the plains, particularly in Transdanubia, where rapid access to the markets of Vienna and Budapest has fostered scientific poultry-farming and bee-keeping. Fish are mainly obtained from the Danube, Tisa and Lake Balaton.

Forestry is of limited importance, for coniferous trees are uncommon and the surrounding highlands are the natural sources of supply. On the plains afforestation with pseudo-acacia and Canadian poplar is increasing to meet the demands for shelter and shade for cattle and houses.

Land mortgage loans granted by the principal financial institu tions in Hungary amounted in 1913 to £167.7 million, or 41% of their capital. The land mortgage loans granted by the same con cerns at the end of 1924 amounted to only f83,000 or 0.3% of their capital. In other words, the land in Hungary was practically free of all mortgage, owing to the depreciation of the currency. In 1926 the 9.3 million hectares of land in Hungary were worth f582.2 million, of which the 5.6 million hectares of arable land were valued at £406.5 million.

Mineral Wealth.

Hungary has few minerals. No Carbonif erous coal exists but Liassic black coal of poor quality is mined in the Mecsek hills. The 1926 output of coal was 6,156,987 metric tons. Lignite is obtained from Tata, south of Esztergom and west of Budapest, the Biikk mountains and at Salgotarjan, north of the Cserhat group. Large quantities of fuel however must be imported from Upper Silesia and Czechoslovakia. Iron-ore is mined near the sources of the Hernad at Rudobanya and upon this depend the iron and steel foundries of the Miskolcz district. Lime and building stone are obtained at various parts of the highland ranges while materials for brickmaking are widespread over the whole country. There are also large deposits of bauxite.

Industries.

The total production of Hungarian industries (present territory) in 1913 amounted to 1,641.6 million gold crowns, and in 1926 to 1,868.8 million gold crowns, i.e., an increase of 13.8%. The production per factory averaged 790,000 gold crowns in 1913 and 620,000 gold crowns in 1926, i.e., a diminution of 21.5%. The value of the average working capacity of one worker was 7,485 gold crowns in 1913 and 9,00o gold crowns in 1926, i.e., a nominal increase of 20.2%.The dominant industries of Hungary are those based upon agriculture, with flour-milling taking first place. The greatest concentration is in Budapest with nearly a hundred large and modern steam mills while all the large towns have important mill ing interests. There are also numerous medium-sized and small enterprises distributed throughout the country using wind or water power. The industry is very sensitive to conditions affecting the crop yield and to the tariff policies of neighbouring countries. Sugar-refining has suffered by the loss of its richest areas of supply but is still an important article of export and prepared in 13 factories. The largest refineries are found at Szerencs in the Hernad valley, at Mezohegyes, Szolnok and Hatvan ; there are also several west of the Raab (output 1926-174,625 tons raw sugar). Spirit and alcohol distilleries using potato, maize and sugar-beet as raw material are numerous in Transdanubia and the Nyirseg district with great concentration in and near Budapest. The quantity produced is about double the home demand and, since a large surplus of raw materials is available, may be expected to increase. Breweries on a commercial scale are centred at Kobanya near Budapest and through shortage of supplies, chiefly Slovakian hops, have declined in production; they are primarily concerned with the home demand. The annual production exceeds 14 million gallons. In addition a thriving malt industry enjoys a good central European market. Leather, based partly on domestic, partly on foreign hides, is prepared in a number of tanneries (49 in 1924), particularly in Budapest, yet still on a scale insufficient for the country's needs.

Tobacco is prepared principally in the capital and near the large tobacco plantations of the north-east, but not on a scale sufficient to meet domestic needs. Other industries include the preparation of foodstuffs, e.g., salami (Budapest, Debrecen and Szeged), and preserved vegetables, vegetable oils and jams (Buda pest and Kecskemet), confectionery, starch and soap, candles and fertilizers, mainly in the capital.

The second group of industries comprises hardware and ma chinery. Pig-iron and steel are prepared at Salgotarjan and Miskolcz (1926 pig-iron-187,812 metric tons; metric tons) and sent to the engineering shops of Budapest and Gyor where the majority of the machine work is concentrated, but foreign supplies are also necessary. Agricultural implements, boats, rolling stock and electrotechnical apparatus are the prin cipal products.

Textile working employs some 35,000 workers in about 200 factories (1924-93,000 spindles, 8,26o looms). Cotton leads and the largest interests are in Budapest, with smaller factories at Papa, Szombathely, Szeged, etc. Budapest is also a centre of woollen manufactures which are, however, better distributed in the larger towns of Transdanubia. Hemp and flax weaving are very important, the former in the Nagy-Alf old (Szeged, Csanad and Bekes), the latter in Transdanubia also; in neither case is the supply sufficient to meet the home demands.

Other forms of industry include limeburning, brickmaking, glassworking in the northern highlands, cement manufacture in the Vertes and Pilis districts and the refining of oil (Budapest).

Foreign Trade.

The figures for the eight years ending 1927 are given in the table on next page.The adverse balance of over £12,000,000 shown by the pro visional figures of 1927 is due largely to the lower foreign prices obtainable for cereals, especially flour. Quantitatively, there does not appear to have been any appreciable decrease in the exports for 1927, and the total agricultural production is increasing. The in crease in imports reflects the improvement of internal purchasing power and the efforts of the Government in the direction of freer trade, as well as cheaper and larger foreign credits. As the in creased imports consist mainly of materials it is reasonable to assume that they will improve national production.

Trade Conventions.

The breaking up of the Austro-Hun garian monarchy, with its single customs union, into seven inde pendent customs territories naturally proved a handicap to close trade relations between Hungary and her neighbours. In the be ginning of 1925 an autonomous customs tariff was brought into force. Although the new duties—partly for the protection of home industries and partly as a basis of bargaining—were relatively high, there was a marked increase of imports, indicating that the duties were by no means prohibitive. By the end of 1927 Hungary had concluded commercial agreements with 20 States on the basis of the most favoured nation clause, and definitive commercial treaties with eight other States on the basis of special tariff con cessions. Negotiations with other and particularly with neigh bouring States were proceeding, though slowly, with a view to sub stituting the existing provisional agreements by definitive treaties. Among the many obstacles was the unwillingness of adjacent States to avail themselves of the direct transit facilities offered by the Hungarian railway lines. As a result of this diversion of traf fic to more roundabout routes, encouraged by artificial rates, Hungary's ton-kilometre railway figures have fallen steadily—an instance of the problems that confront any solution of the eco nomic difficulties in the Danubian basin.

Administration and Education.

Hungary is now a mon archy without a king, governed by a regent, Admiral Horthy. Its legislature comprises two houses, an upper and a lower. The former contains six classes of members, viz.:—(1) Elected representatives of former hereditary members, about 38 in num ber, (2) Members elected by County and Municipal authorities, about 5o, (3) Heads of representative religious communities, about 31, (4) certain distinguished personages, e.g., judges and high State officials, (5) representatives of scientific bodies and chambers of commerce, about 4o, and (6) Life members nomi nated by the regent. The Lower House numbers 245 members, 200 of whom are representative of rural constituencies and elected by open ballot.The franchise is granted to males of more than 24 years who have satisfactorily completed an elementary school course and to females of more than 3o years if earning their own living, or with a satisfactory proof of higher education, or the wives of graduates of high schools or colleges, or the mothers of three children. Local administration is not so forward and is subject to much governmental control. Two divisions exist, viz.:—(1) communes where the representative body consists half of mem bers elected for six years and half of heavy taxpayers, with an official body whose members are appointed for life. All persons of more than 20 years who have paid State taxes for two years are enfranchised; (2) the counties and towns ranking as inde pendent, each class being a representative body similar to that of the Communes elected for six years, with an executive com mittee of officials.

Education has rapidly improved in recent years but is com pulsory only between the ages of 6 and 12. According to 1920 statistics 15.4% of the population over 6 years was illiterate. Educational institutions are divided into a number of classes including infants, elementary, primary, industrial and commercial, secondary, training colleges, technical high schools, universities and certain special grades, e.g., religious and legal. In the period 1925-26 there were 6,438 elementary schools with 656,349 pupils and 16,705 teachers; 1,092 agricultural schools, 400 schools for apprentices, 366 of these being for industrial workers, the re mainder for commercial students, 43 training colleges for ele mentary teachers, 375 primary schools with 87,161 pupils and 3,892 teachers and 6 training colleges for primary teachers. The middle schools, comprising gymnasia, real schools, etc., provide a course covering 8 years and out of 61,757 pupils more than 50,000 are boys. The universities are located at Budapest (1926 5,393 students), Debrecen (952), Pecs (1,005) and Szeged (1,135), while there are also about 120 schools offering special ized agricultural, industrial and commercial courses.

Rearrangement of frontiers, following the Treaty of Trianon 1920, has altered the course of much of Hungarian economy especially in the east where the old market towns have been lost, but Budapest (q.v.) has always gathered to itself by a zone system of communication and other means many of the threads of life within the present limits of the country and, as the centre and source of inspiration of a State with a "keystone" position astride the middle Danube, can yet do much to restore the country to prosperity, to foster the progress of eastern Europe and to link it more closely with the West.

See the Statistical publications of the Hungarian government and F. Fodor, Conditions of production in Hungary (Budapest, 1921) ; G Prinz, Siedlungsformen in Ungarn Ungarische Jahrb: vol. 4 (Berlin, 1924) ; E. Horvath, Modern Hungary 166o-192o (Cambridge, 1923) ; E. Halmay, La Hongrie d'aujourd'hui (Budapest, 1925) ; E. Czekonacs, Hungary, new and old (Budapest, 1926) ; Illes and Halasz, Hungary before and after the War in economic-statistical maps (Budapest, 1926) . The following, though concerned principally with pre-war Hungary, contain useful geographical data:—E. Cholnoky and others, Ungarn Land and Volk (Leipzig, 1918) ; A. Hevesy, Nationalities in Hungary (London, 1919) ; F. Heiderich, Wirtschaftsgeographie Karten and Abhandlungen zur Wirtschaftskunde der (Lander der ehemaligen) osterreichisch-ungarischen Monarchic (Vienna, 1916-22).

(W. S. L.; W. Go.) Defence.—The strength of the present-day Hungarian Army is governed by the provisions of the Treaty of Trianon, signed in June 1920, which abolished compulsory service, limited the strength of the army to a total of 35,000, including officers and depot troops, laid down a maximum and minimum establishment for army formations, prescribed the length of service for all ranks, limited the manufacture of arms and munitions and forbade their import, and also forbade all natures of "mobilization." The terms were similar to those imposed upon Austria (q.v.).

Recruiting is by voluntary enlistment for 12 years service, of which 6 may be spent on furlough, with facilities for extension of service. Until July 1922 all officers had served in the old army, with an obligation not to retire until the age of 4o. Vacancies are now filled by cadets who have spent 4 years at the Military School. Service in the Hungarian Police and Royal Hungarian Gendarmerie is for 20 years for officers, 6 for other ranks, with facilities for extension. The budget strength of the army accord ing to latest returns was 34,708 including 1,478 officers and the gendarmerie and police 9,598, including 1,440 officers.

The Higher Command includes the military bureau of the Gov ernor, the ministry of national defence with the army commander in-chief and inspectors of the different arms, the Budapest fortress command, the Varpalota garrison command and various inspec torates. The peace distribution of the army is on a territorial basis, its functions, according to treaty, being confined to main taining order and to "controlling the frontiers." There is no mili tary air service. An agreement has been arrived at for the control of civil aviation in Hungary.

See also League of Nations Armaments Year-book (Geneva, 1928) .

(G. G. A.) Budget.—According to the programme of reconstruction drawn up in mutual agreement by the League of Nations and the Hun garian Government a deficit of £4.2 million was estimated for the first fiscal year-1924-25—of the reconstruction period, but in fact that financial year closed with a surplus of £3.8 million. For 1925-26 provision was made in the programme of reconstruction for a deficit of £2.1 million, but instead there was a surplus of £3.4 million. These favourable results were improved upon in the fiscal year 1926-27, when—in spite of appreciable reduction in taxation—there was a record surplus of Q5.2 million.

Of the 253,800,000 gold kronen which were raised under the auspices of the League of Nations for Hungarian reconstruction only 69,500,000 gold kronen, or less than 28%, were actually used to cover budget deficits and that was in the first half year of the reconstruction period. It was thus possible to use the bal ance of the loan as a productive investment for the development of Hungary's economic life between 1925 and 1928. In Dec. 1927, the League released the last portion of the loan, viz., 33 million gold kronen, for productive investment in Hungary during the fiscal year 1928-29. The various surpluses of the budgets recorded above were used for the same purpose.

In the fiscal year 1927-28, the following were the principal items of the Budget:— Million pounds sterling.

State debts . . . . . . . . . . 3.236 Treaty charges . . . . . . . . . . 0• 2 09 Expenditure for personnel . . . . . . • • 9.114 Subsidies to independent administrations for personnel and pensions • 1.647 Pensions . . . . . . . . . . . Total, with other expenditure . . . 27,089 Revenue . 2 7,o96 Estimated surplus . . . . . . . . 10.00 7 The total expenditure of the State is covered by taxation and departmental receipts. State enterprises are separated from State administration. These enterprises—posts, telegraphs, telephones, state railways, state iron, steel and machine works, state domains and forests, silk production, coal-mining and the postal savings banks—are operated without a charge on the budget. In 1927-28 they were paying their way and had a surplus for investment pur poses.

State total Hungarian State debt amounted to £329,800,000 sterling before the war, which represents a burden of £15.7 per capita of population. The debt of present Hungary, as constituted under the Peace Treaty, amounted (reparation debt not included) to L57,255,000 sterling at the end of June 1927, due allowance having been made for the allocation of the pre-war debt and of part of the war debt as provided by the Peace Treaty. Of this amount £3,509,000 represents the funded internal debt, the funded foreign debt and £9,171,000 the floating debt. The burden per capita of the population amounts to £6.8, much less than the pre-war burden, mainly in consequence of the depreciation in the value of the internal obligations of the State.

Savings and Hungarian Government contracted no foreign or other loans after the League loan was raised, and steadfastly refused to give its guarantee to any non-Governmental loan. It obtained from parliament wide powers for controlling foreign borrowing by municipal and other bodies. These powers were used drastically, and the Government have only approved foreign borrowing in cases where production would be increased. The eagerness, however, of foreign lenders to give credit to Hun garian enterprise—especially dollar credits—made the position often rather difficult. How the credit situation changed in Hun gary can be judged from the fact that whereas in 1925 the first Cities loan could only be contracted in New York at 82, with 72% interest, in May 1927 the City of Budapest obtained $20,000, 000 at a net price of 882, at 6% interest. Towards the end of 1927 the Association of Hungarian Mortgage Institutes raised $7,000,000 at 932, with 7% interest. The service of foreign loans represented in 1927 only 2.8% of the national income.

Internal savings accumulated steadily. Deposits in the postal savings bank and in the 13 principal Budapest banks amounted on Dec. 31, 1927, to 56.3% of the pre-war figure—the total being 137,636,200. This contributed to the reasonableness of the rates of interest prevailing in Hungary. These were between 7% and 9i% in Budapest, according to the standing of the borrower, anti between 8% and 12% in the rural districts at the end of 1927. The bank rate was unchanged during 1927 at 6% as compared with 121% in March 1925.

Taxation.—Prior to the middle of 1924, the start of recon struction, the Hungarian Government had recourse to various taxation expedients and coercive measures in order to protect the revenues from the then ever-depreciating currency. Owing to the war, the revolution and the Rumanian occupation, there were also outstanding arrears due for some three or four years which had lost almost all value in consequence of the intervening deprecia tion of the krone.

Faced with these conditions, the Government in 1920 raised a forced loan by the stamping of notes—amounting to 5o% of the currency then in circulation. In 1921 the turn-over tax was intro duced, which amounted at first to 1.5% and later to 3% on the sale price of each article and on each handling. Thus, in many instances, it amounted to a tax of 12%. In 1922 land taxes were made payable in wheat or wheat values with a view to obtaining revenue in a non-depreciating medium. At the beginning of 1924 the Government was again compelled to resort to another forced loan from those liable to property and income tax.

In the course of the reconstruction the collection of taxes in wheat was dropped; in Aug. 1925 the turn-over tax was reduced from 3% to 2%, and in Feb. 1926 the State's participation in house rents was abolished.

In consequence of the constantly increasing State revenues, the Government, at the beginning of 1927, continued the alleviation of the tax burden, which was retarding economic recovery. The land tax and the house tax were both reduced, but the proceeds of the latter continued to rise as house rent restrictions were gradually abolished. The tax-free minimum exemption from income tax was slightly raised, the rates of the taxes were reduced, and the more important foodstuffs were completely exempted from the turn over tax. In spite of these reductions State revenues did not de crease, thanks to the improvement in general conditions.

In the financial year ending June 30th, 1927, the revenues de rived by the State from direct taxes were divided as follows: house tax, 51.8; income tax, 47-9; land tax, 40.6; corporation tax, 13.2 ; property tax, 12.5 ; sundry taxes, o.k ; total, 166.4 million pengos.

In the same fiscal year indirect taxation yielded 564.4 million pengos. The total burden of State and municipal taxation was roughly estimated at about 88.3 pengos.

Currency.—During the existence of the Dual Monarchy, Hun gary and Austria had a joint monetary system and a joint bank of issue. After the outbreak of the revolution the Austro Hungarian bank was able for some time to continue its work in Hungary, but the Bolshevik regime seized the entire stock of notes. When these began to run short the Soviet republic issued its own notes. After the collapse of Soviet rule in 1919, the Hun garian Government issued the necessary decree to enable the Austro-Hungarian bank to continue its statutory work as "man ager of the Hungarian business of the Austro-Hungarian bank." In March 1920 the Government ordered the stamping of the notes of the Austro-Hungarian bank which were in circulation within the country, and requisitioned 5o% of these notes as a forced loan in order to secure, so far as possible, the carrying on of the State administration without constant application to the note printing press. As the creation of a special issuing institu tion appeared to be inevitable in consequence of the liquidation under the Peace Treaties of the Austro-Hungarian bank, the State itself provisionally established the Royal Hungarian State Note Institute (M. Kir. Allami Jegyintezet), which began its activities on Aug. 1, 1921. The notes of the Austro-Hungarian bank, which had been provided with the Hungarian stamp, were exchanged in the same year against State notes.

When the State Note Institute commenced its work, the financial and economic position was such as to compel the State to cover its budgetary requirements not from revenues but by means of the note printing press. This naturally resulted in the gradual depreciation of the crown. The forced loan raised by stamping notes had covered the budget deficit only for a short time. In 1921 the Government had recourse to a non-recurring capital levy, but by the time most of the proceeds reached the treasury the value of the crown had so depreciated as to nullify these efforts. In the first half of 1921 the exchange rate of the crown rose tem porarily in Zurich from 1•05 to 2.85 Swiss francs (ioo crowns), owing to the impression created by the taxation and other plans of the then minister of finance, M. Hegedus. When it was seen that these plans were impossible of reali zation, and as Hungary's balance of pay ments became more and more unfavour able, the crown continued to fall, until in March 1924 it reached 0•0085 Swiss francs for 10o crowns. As a result of long nego tiations the League of Nations loan was raised, and the restoration of normal eco nomic and currency conditions was thus made possible (see Political History). All restrictions in foreign exchange were abolished in Oct. 1925.

On Dec. 31, 1925, the currency per capita of the population was approxi mately 43 gold crowns. In the latter part of 1925 the new monetary unit was chosen and named the pengo, divided into ioo filler; 3,80o new units go to I kg. of fine gold, so that I pengo contains grammes of fine gold. The currency re form law passed on Nov. 6, 1625, provides for the minting of gold coins for 20 and 10 pengos from an alloy consisting of 90o parts of gold to ioo parts of copper, so that 3,420 pengos will be struck from I kg. of this alloy. The National bank is required to buy gold in bars at a fixed price without limit, and on demand. Silver coins of one pengo can be put into circulation to a total nominal value of not more than 45,000,000 pengos.

From Jan. I, 1927, the pengo was the obligatory unit of account in Hungary. The rate of conversion from the old to the new cur rency was I2,500 paper crowns to one pengo, or one gold crown 1.1585365 pengo. I pengo is therefore equal to 0.0359388 pound sterling or 0.1748985 dollar.

Central Bank.—The re-establishment of an independent bank of issue was in the forefront of the programme of reconstruction. The Hungarian National bank was founded, with a capital of 30,000,00o gold crowns and commenced its activities on June 24, 1924. From that day the State notes then in circulation were re garded as bank notes. Under its statutes the bank is precluded from lending to the State, and is required to maintain against its note circulation, plus sight liabilities minus State debt, a per centage of cover in precious metal and stable foreign exchanges, on an ascending scale, beginning at 20% during the first five years. The bank return of Dec. 31, 1927, showed the proportion of cover to be 46.4%. Since July 1924 the currency has been stable on a sterling basis. In Oct. 1925 the basis of stabilization became gold, and all restrictions on dealings in foreign exchange were abolished.

The following table shows the development of the note circulation:— the above mentioned bank-notes-1 pengo coins, and 5o, 20, I0, 2 and I filler small coins to the nominal value of 40,258,639,39 pengos.

BIBLIOGRAPHY. Monthly

Reports of League Commissioner-General Bibliography. Monthly Reports of League Commissioner-General Jeremiah Smith (Geneva) ; Revue Hongroise de Statistiques (Buda pest) ; Department of Overseas Trade Reports, (1925).(W. Go.) The history of the countries which were later to constitute the kingdom of Hungary, up to the close of the Roman period, will be found under PANNONIA and DACIA. The Romans were suc ceeded by Germanic tribes, and they in turn by the Huns (q.v.). After the death of Attila (455), his kingdom declined, and Ger manic (Gothic) tribes again entered Pannonia and Dacia. The 6th century A.D. found the Lombards established in Pannonia, the Gepidae in Dacia. In 567 the Avars (q.v.), allying themselves with the Lombards, crushed the Gepidae, and in the following year occupied Pannonia, the Lombards migrating to Italy. As the Avar kingdom declined, the western and northern portions of Hungary recovered independence under Slavonic rulers. In 791 797 Charlemagne crushed the Avars, and established the first Ostmarks (see AUSTRIA) which probably occupied all the land be tween the Danube and the Save. North of the Danube, the im portant Slavonic kingdom of Moravia (q.v.) was founded about 828, while the heritage of the Avars east of the Danube is believed, on slight authority but with great probability, to have been under the suzerainty of the Bulgars.

Arrival of the Magyars.—In 894 the Magyars (q.v.) made their first authenticated raid into Moravia. The early history of this race is still a matter of learned dispute. Their own traditions declare them to have entered Hungary first with the Huns; leav ing it, to have sojourned somewhere in eastern Europe (both the Caucasus and the Volga are mentioned in these traditions) and then to have crossed the Don, passed by Kiev, and re-entered Hungary through the Vereczka pass. It is certain that they were in south-east Russia in the 9th century, if not before, and probably between the Don and the Kuban rivers; and they appear at one time to have been vassals of the Khazars (q.v.). Driven westward by the Petchenegs (q.v.) they arrived at the mouth of the Danube in 889; expelled thence by the Petchenegs and Bulgars, they en tered Pannonia for final settlement in 895 or 896, under their leader, Arpad. They easily subdued the scattered population of the central plain, crushed the empire of Great Moravia in 906, and defeated the German forces gathered to meet them in 907. They were now firmly established in Hungary; although Transylvania was probably not truly conquered until at least a century later.

During the following 7o years we know little of the internal his tory of the Magyars. Arpad died in 907, and his immediate suc cessors, Zsolt (907-947) and Taksony (947-972), are little more than chronological landmarks. During this period the Magyar horsemen ravaged Thuringia, Swabia and Bavaria, and defeated the Germans on the Lechfeld in 924, whereupon the German king, Henry I., bought them off for nine years, employing the respite in reorganizing his army. In 933 the war was resumed, and Henry defeated the Magyars at Gotha and at Ried (933). The only effect of these reverses was to divert them elsewhere. In 934 and 942 they raided the Eastern empire, and were bought off under the very walls of Constantinople. In 943 Taksony led them into Italy, and in 955 they ravaged Burgundy. The same year the emperor Otto I. overwhelmed them at the famous battle of the Lechfeld (Aug. Io, 955). This catastrophe convinced the leading Magyars of the necessity of accommodating themselves as far as possible to the empire, especially in the matter of religion. Christianity had already begun to percolate Hungary. The only question was which form of Christianity were the Magyars to adopt, the eastern or the western? Alarmed at the sudden revival of the Eastern empire, which under the Macedonian dynasty ex tended once more to the Danube, thus becoming the immediate neighbour of Hungary, Duke Geza, who succeeded Taksony in 972, resolved to accept Christianity from the more distant emperor of the West. Accordingly an embassy was sent to Otto II. at Quedlinburg in 973, and in 975 Geza and his family were baptized.

During his reign, however, Christianity did not extend much be yond the limits of his court.

Stephen I.

Geza's successor, Stephen I. (q.v.), was one of the great constructive statesmen of history. His reign resulted in the firm establishment of the Hungarian church and the Hungarian State: in 1001 Pope Silvester II. recognized Mag yar nationality by endowing the young Magyar prince with a kingly crown. Hungary was divided into dioceses, with a metro politan see at Esztergom (Gran). But the Benedictines, whose settlement in Hungary dates from the establishment of their monastery at Pannonhalma (c. were the chief pioneers. The monks built villages for the colonists who flocked to them, teaching the people western handicrafts and methods of agricul ture; and they were soon followed by foreign husbandmen and handicraftsmen, who were encouraged to come to Hungary by re ports of the abundance of good land there and the promise of privileges.In endeavouring to establish his kingship on the Western model Stephen based his new principle of government, not on feudalism, but on the organization of the Frankish empire. Central and west ern Hungary (the south and north-east still being desolate) were divided into 46 counties. At the head of each county was placed a count nominated by the king, whom he was bound to follow to battle, and to whom he was responsible. Two-thirds of the rev enue of the county went into the royal treasury, the remaining third the count retained for administrative purposes. It is sig nificant for the whole future of Hungary that no effort was or could be made by Stephen to weld the heterogeneous races under his crown into a united kingdom ; the non-Magyars, unless, as was frequently the case, granted special privileges, were ruled by the royal governors as subject races, forming—in contradistinction to the "nobles"—the mass of the peasants, upon whom until 1848 nearly the whole burden of taxation fell. The right, not often exercised, of the Magyar nobles to meet in general assembly and the elective character of the Crown, Stephen also did not venture to touch.

A troubled 4o years (1038-77) divides the age of St. Stephen from the age of St. Ladislas. In 1046 and 1061 there were two dangerous pagan risings, while from the south and south-east two separate hordes of fierce barbarians (the Petchenegs in 1067-68, and the Cumans in 1071-72) burst over the land. For a time Hungary was in great danger of being forced into dependence on the German empire. In 1041 the emperor, Henry III., made an excuse of the fugitive king Peter's appeal for help, to ravage Hungary, and after his victory at Menf o (July 5, 1044) he re stored Peter and received an oath of fealty from him. In 1051 and 1052 Henry again invaded Hungary but was defeated by An drew I. (1046-66) and his brother Bela, afterwards king Bela I. (1060-63). Finally the attention of the emperor, Henry IV., was distracted from his Hungarian ambitions by the outbreak of the investiture conflict (1076), when Geza I. shrewdly applied to Pope Gregory VII. for assistance, and submitted to accept his kingdom from him as a fief of the Holy See. The immediate result of the papal alliance was to enable Hungary, under both Ladislas I. and his capable successor Koloman (Kalman) 1116), to extend her dominion abroad by conquering Croatia and part of the Dalmatian coast. By a series of laws Ladislas im proved the administration of justice and the local government of the counties, while Koloman regulated and simplified the whole system of taxation, and promoted trade by a systematic improve ment of the ways of communication. The magna via Colomanni regis was in use for centuries after his death.

Rivalry with the Eastern Empire.

Throughout the greater part of the 12th century the chief impediment in the way of the external development of the Hungarian monarchy was the Eastern empire, which, under the first three princes of the Comnenian dynasty, dominated south-eastern Europe. On the accession of Manuel Comnenus in 1143 the struggle became acute. Manuel, who was the grandson of St. Ladislas and had Hungarian blood in his veins, aimed at the suzerainty of Hungary, by placing one of his Magyar kinsmen on the throne. He successfully supported the claims of three pretenders to the Magyar throne, and finally made Bela III. king of Hungary, on condition that he left him, Manuel, a free hand in Dalmatia. The intervention of the Greek emperors had important consequences for Hungary. Polit ically it increased the power of the nobility at the expense of the Crown, every competing pretender endeavouring to win adherents by distributing largesse in the shape of Crown-lands. Ecclesiasti cally, it weakened the influence of the Catholic Church in Hun gary, the Greek Orthodox Church, which permitted a married clergy and did not impose the detested tithe, attracting thousands of adherents even among the higher clergy. But the Eastern em pire ceased to be formidable on the death of Manuel (118o), and Hungary helped materially to break up the Byzantine rule in the Balkan peninsula by assisting Stephen Nemanya to establish an independent Serbian kingdom, originally under nominal Hungarian suzerainty. Bela conquered Galicia and took the title "Rex Galiciae"; he endeavoured to strengthen his own monarchy by introducing the hereditary principle, crowning his infant son, Emerich, as his successor during his own lifetime, a practice fol lowed by most of the later Arpads.

The Golden Bull.

Unfortunately his two immediate succes sors, Emeric (1196-1204) and Andrew II. (1205-35), weakened the royal power in attempting to win support by lavish grants of the Crown domains, they increasing the already excessive influence of the Magyar oligarchs. In 1222 the so-called Golden Bull was promulgated. It has been called the Magna Carta of Hungary, but really constituted an attempt to defend the monarchy by strength ening the lesser nobles against the magnates. Feudalism was at tacked by decrees that the title and estates of the lords-lieutenant of counties should not be hereditary. On the other hand, the prin ciple of the exemption of all the nobles from taxation was con firmed, as well as their right to refuse military service abroad.Bela IV. (1235-1270) is best known as the regenerator of the realm after the subsidence of the Tatar deluge of 1241-42 (see MLA IV.), but his two great remedies, wholesale immigration and castle-building, only sowed the seeds of fresh disasters. Thus the Cuman colonists, mostly pagans, whom he settled in vast numbers on the waste-lands, threatened to overwhelm the Christian popu lation; while the numerous strongholds, which he encouraged his nobles to build as a protection against future Tatar invasions. sub sequently became so many centres of disloyalty. To bind the Cumans still more closely to his dynasty, Bela married his son, Stephen V. (127o-72), whom he had crowned "junior rex" in 1254, to a Cuman girl. Neither Stephen nor his son, Ladislas Iv. (1272-90), was strong enough to make headway against the disintegrating influences all around him. The latter was so com pletely caught in the toils of the Cumans that the Holy See was forced to intervene to prevent the relapse of the kingdom into barbarism, and Ladislas perished in the crusade that was preached against him. His successor, the last Arpad, Andrew III. (1290- 1301) , though he conducted a successful war against the emperor Rudolph, who claimed Hungary for his son Albert, as a vassal State, was yet incapable of controlling the Hungarian magnates. After eight years' civil war (1301-08) the crown of St. Stephen finally passed into the capable hands of Charles Robert of Anjou.

During the Arpad dominion the nomadic Magyar race had adopted western Christianity and founded a national monarchy on the western model. While the monarchy was absolute, and thus able to concentrate in its hands all resources of the State. Hungary successfully withstood pagan reaction from within and pressure from without. But the weakness of the later Arpads, the depopulation of the realm during the Tatar invasion, and the civil discords of the 13th century, brought to the front a powerful class of barons which gradually absorbed the ancient county system, while the ancient royal tenants became the feudatories of the great nobles. This political revolution met with determined op position from the Crown, which resulted in the utter destruction of the Arpads.

House of Anjou.

It was reserved for the two great princes of the house of Anjou, Charles I. (1308-42) and Louis I. "the Great" (1342-82), to rebuild the Hungarian State. Their task was made easier by the decimation of the Hungarian magnates during the civil wars. Both these monarchs were absolute. The national assembly (Orszaggyiiles) was still summoned occasionally, but the real business of the State was transacted in the royal council, where the able men of the middle class, principally Italians, held confi dential positions. The lesser "gentry" were protected against the tyranny of the magnates, and the growth of towns encouraged by grants of privileges. Under Charles the whole fiscal system was reformed, and Louis established a system of protective tariffs. A law of 1351 which, while it confirmed the Golden Bull in gen eral, abrogated the clause (iv.) by which the nobles had the right to alienate their lands, was enacted to preserve the large feudal estates as part of the new military system. Louis's efforts to in crease the national wealth were largely frustrated by the Black Death, which ravaged Hungary from 1347 to 1360, and again dur ing 138o-81, carrying off at least one-fourth of the population. The foreign policy of the Angevin kings was on the whole suc cessful. Charles married Elizabeth, the sister of Casimir the Great of Poland ; he reconquered the Banate of Macso from Serbia, and subdued Bosnia in 1328. Louis, by virtue of a compact made by his father 31 years previously, added the Polish crown to that of Hungary in 1370. Thus, during the last 12 years of his reign, the dominions of Louis the Great included the greater part of Central Europe, from Pomerania to the Danube, and from the Adriatic to the Dnieper.The Angevins were less successful towards the south, where the first signs of the Turkish menace were appearing. In 1353 the Ottoman Turks crossed the Hellespont from Asia Minor; in 1360 they conquered southern Bulgaria. In 1371 they penetrated to the heart of old Serbia. In 1380 they threatened Croatia and Dal matia. Hungary herself was now directly menaced. The Arpad kings had encircled their whole southern frontier with military colonies, largely composed of non-Magyar nationalities. But a re distribution of territory had occurred in these parts, which con verted most of the old banates into semi-independent and violently anti-Magyar principalities, while in Walachia and Moldavia the growing Vlach nation threw off the shadowy Hungarian yoke altogether in the 14th century (see RUMANIA). In Bosnia the per sistent attempts of the Magyar princes to root out the sect of the Bogomils (q.v.) had alienated the Bosnians, and in 1353 Louis was compelled to buy the friendship of Tvrtko by acknowledging him as king of Bosnia. Both Serbia and Bulgaria were by this time split up into half a dozen principalities which, for religious and political reasons, preferred paying tribute to the Turks to ac knowledging the hegemony of Hungary. Thus, towards the end of his reign, Louis found himself cut off from the Greek emperor, his sole ally in the Balkans, by a chain of bitterly hostile Greek Orthodox States, extending from the Black sea to the Adriatic.

At the death of Louis the Great in 1382, his young daughter Mary, who was betrothed to Sigismund of Luxembourg, was crowned queen ; but the Horvathys, a great Croatian noble fam ily, offered the crown to Charles III. of Naples, who accepted it, and was crowned as Charles II. on Dec. 31, 1385. Thirty-eight days later he was murdered at the instigation of the queen dowager, Elizabeth, who was determined to rule Hungary during her daughter's minority. In July of the same year Elizabeth was murdered in her turn, by the Horvathys. Mary herself would doubtless have shared the same fate, but for the speedy interven tion of her fiancé, Sigismund, whom a diet, by the advice of the Venetians; had elected king on March 31, 1387. He married Mary in June the same year, and she shared the crown with him till her death in 1395. Louis the Great's other daughter, Hedwig, was crowned queen of Poland (1384) and forced to marry Jagello, grand-duke of Lithuania.

Sigismund.

During the long reign of Sigismund (1387 1437), who was crowned Holy Roman emperor in 1410, Hungary was confronted with the Turkish peril. The insubordination of the feudal levies was largely responsible for the defeat of the corn bined armies of Christendom, under Sigismund's leadership, at Nicopolis, in 1396; and the king was hampered, at a time when he might have taken advantage of the collapse of the Turks before the Tatars under Tamerlane, by the enmity of the pope, who sad dled him with a fresh rebellion of the Magyar nobles (who set up Ladislas of Naples as king in 1403, but were suppressed at Papocz), and two wars with Venice, resulting ultimately in the total loss of Dalmatia (c. 143o). After the recovery of the Turks under Mohammed I. and Murad II. (1421-51), Sigismund, real izing that Hungary's strategy must be strictly defensive, elabo rately fortified the whole southern frontier, and converted the little fort of Nandorfehervar (Belgrade), at the junction of the Danube and Save, into an enormous first-class fortress. In 1435 he carried out an army-reform project, by which the nobles and principal towns were bound to maintain a banderium of 500 horsemen, or a proportional part thereof, thus supplying the Crown with a standing army.Sigismund's need of money forced him to conciliate the diet, which was essentially an assembly of notables, lay and clerical, though free and royal towns were invited to send deputies to the diet of 1397. Sigismund was on good terms with his nobles, who supported him against attempted exactions of the popes; but it was at this time that feudalism began to spread over Hungary and especially in the wild tracts where the king's writ did not run. Simultaneously from the west came the Hussite propagan dists teaching that all men were equal, and that all property should be held in common. The result was a series of dangerous popular risings (the worst in 1433 and 1436) in which heresy and com munism were inextricably intermingled. With the aid of inquisi tors from Rome, the evil was literally burnt out, but not before provinces, especially in the south and south-east, had been utterly depopulated. They were repeopled by Vlachs.

Sigismund was succeeded in 1438 by Albert V., duke of Austria, who had married his only daughter, Elizabeth. In the same year he was elected king of the Romans and crowned king of Bohemia. In 1439 he died of dysentery, in the course of a campaign against the Turks. The widowed queen was about to bear a child, which if it turned out to be a son, would be heir to the throne ; but the leading nobles, fearing the results of a long minority, offered the crown to Wladislav III., king of Poland, who accepted it in March 1440 and was crowned in July as Wladislav I. In the meantime Queen Elizabeth had given birth to a son, who was crowned in May as Ladislas V., and she appealed for help to the emperor Frederick III. and to the Hussite leader, John Giskra. The re sulting civil war was terminated only by the death of Elizabeth on Dec. John Hunyadi.—All this time the pressure of the Turks upon the southern provinces of Hungary had been continuous, but their efforts had so far been frustrated by the ban of Szoreny, John Hunyadi, the fame of whose victories, notably at Nagyszeben in 1442 and near Sofia in 1443, encouraged the Holy See to place Hungary for the third time at the head of a general crusade against the infidel. The king accepted the leadership of the Christian league, and was on the point of quitting his camp at Szeged for the seat of war, when envoys from Sultan Murad arrived with the offer of a ten years' truce on such favourable conditions that Hunyadi persuaded the king to conclude the peace of Szeged in July. Two days later the papal legate, Cardinal Cesarini, absolved the king from his promise to observe the peace, and in November the latter suffered death and overwhelming defeat at Varna. (See HUNYADI, JANOS.) The diet of 1446 now elected Hunyadi governor of Hungary. Before he could turn his attention to the Turks, Hunyadi had to negotiate with Jan Giskra, a Hussite mercenary who held the wealthy mining towns, nominally for the infant king, Ladislas V., still detained at Vienna by his kinsman, the emperor, while the western provinces were held by Frederick himself. At the same time Hunyadi was thwarted by the great nobles, who resented the position to which he had risen. He lost the battle of Kosovo in 1448 owing to treachery, and it was at his own expense that he fortified Belgrade in forcing Mohammed II. to raise the siege and return to Constantinople in 1456. Hunyadi died in camp in the same year, and after the murder of his elder son, Laszlo (1457), and the death of Ladislas V. six months later, Matthias Hunyadi, the younger son, was elected king as Matthias I. (q.v.) on Jan. 23, 1458.

In 1459 the emperor Frederick II. was elected king of Hungary by a party of nobles, but by a treaty of 1462 he was finally forced to recognize Matthias as king. After a victorious campaign against the Turks in 1463, Matthias turned his attention to Bohemia. In 1468, with the sanction of the emperor and of the pope, who had declared Podiebrad of Bohemia to be a usurper, he entered that country, and in 1469 was crowned king by the Catholic nobles; but by the Peace of Olmutz (1478) Matthias was obliged to recognize the right of Wladislav, Podiebrad's successor, to share the title of king, and to rule over all except Moravia, Silesia and Lausitz. To do all this Matthias was compelled to take in hand the question of army reform. Putting aside the old feudal levies, he formed the nucleus of a standing army by recruiting mercen aries from the Magyars, Czechs and Croatians. Matthias used this army as a police force to maintain order and to collect taxes where they were refused.

Despite the enormous expense of maintaining the army, Mat thias, after the first ten years of his reign, was never in want of money. By this time the gentry took part in the legislature. But the poorer deputies frequently agreed to make grants for two or three years in advance, so as to be saved the expense of attending every year, and allowed the king to assess as well as to collect the taxes, which consequently tended to become regular and perma nent. Matthias re-codified the Hungarian common law, cheapened and accelerated legal procedure, and created an efficient official class. He founded the University of Pressburg (Academia Istro politana, 1467) and revived the declining University of Pecs. He also laboured strenuously to develop and protect the towns, multi plied municipal charters, and materially improved the means of communication. His Silesian and Austrian acquisitions were also very beneficial to trade, throwing open as they did the Western markets to Hungarian produce.

Throughout Matthias's reign the Eastern question was never acute; on the Turkish invasion of Transylvania in 1479, he won another great victory at the Field of Bread (Kenyermezo) on Oct. 13, and only after his death did the Ottoman empire become a menace to Christendom. His hands were tied by the unappeasable enmity of the emperor and the emperor's allies. In 1477, and again in 1485, Matthias was provoked to lay siege to Vienna; the second time, when the city fell (June 1), Matthias annexed Aus tria, Styria and Carinthia, and transferred his court to Vienna, where, on April 6, 1490, he died.

Period of the reign of Janos (John) Corvinus, the natural son and successor of Matthias, came the reaction against the latter's purely personal, and therefore artificial, domin ion (see CoRVINUS, JANOS). The nobles and prelates, who de tested the severe and strenuous Matthian system, found a mon arch after their own heart in Wladislav Jagello, since 1471 king of Bohemia, who as Wladislav II. (1490-1516) was elected unani mously king of Hungary by the assembly of Rakos on July 15, 1490. Wladislav was, from first to last, the puppet of the Magyar oligarchs. At the diet of 1492 he consented to live on the receipts of the treasury, which were barely sufficient to maintain his court, and engaged never to impose any new taxes on his Magyar sub jects. The dissolution of the standing army, including the Black Brigade, was the immediate result of these decrees, and the dis graceful peace of Pressburg was concluded between Wladislav and the emperor Maximilian on Nov. 7, 1491, whereby Hungary re troceded all Matthias's Austrian conquests, together with a long strip of Magyar territory, and paid a war indemnity equivalent to £200,000.

The 36 years which elapsed between the accession of Wladislav II. and the battle of Mohacs are the most melancholy and dis creditable period of Hungarian history. The prelates and mag nates enjoyed inordinate privileges, while openly repudiating their primal obligation of defending the State against extraneous ene mies. The great nobles were often at perpetual feud with the towns, whose wealth they coveted. Everywhere the civic com munities were declining. Many of them, notably Visegrad, were deprived of the charters granted by Matthias. The whole burden of taxation rested on the shoulders of the peasants.

The condition of the peasants at this time was very wretched, and in 1514 large numbers of them, who had been assembled by Bakocz for a crusade against the Turks, broke out into rebellion instead, under the leadership of Gyorgy Dozsa (q.v.). After the suppression of the rising by the nobility, under John Zapolya, the "Savage Diet" met to punish the rebels. The peasants were hence forth bound to the soil and committed absolutely into the hands of "their natural lords." About the same time, at the instance of the diet in Verboczy drew up the Tripartitum, the famous codification of Hungarian customary law, which sanctioned the liberties of the great class of Hungarian nobles as against the sovereign and the peasantry. Though never formally passed into law, it continued until 1845 to be the only document defining the relations of king and people, of nobles and their peasants, and of Hungary and her dependent States.