Hydraulic Machinery

HYDRAULIC MACHINERY, the name given to certain types of machines which utilize water pressure for motive power. Under high pressure, water forms a very convenient medium for operating slow-moving machinery of the piston type in which large forces are involved and where easy and precise regulation is required. Where the main pressure supply is of less intensity than is required to work the hydraulic machinery an intensifier is used. In its simplest form this consists of a ram of area a, carrying a piston of larger area A (fig. I ). Water from the pres sure mains, at pressure p, is admitted behind the piston and compresses the water in the ram cylinder to an increased pressure P. If w is the weight of the ram and piston and F is the frictional resistance of the packings : Lifts and Hoists.—Probably in the aggregate more power is used by lifts and hoists than by any other class of hydraulic machinery, and for such work as this, hydraulic transmission is particularly suit able. Several types of lift are in use, these consisting of modifications of the simple direct-acting or of the suspended type. The former consists of a hydraulic cylin der sunk vertically in the ground, of length slightly greater than the maximum travel of the lift and fitted with a ram which carries the lift cage at its upper end. Pres sure water is admitted below the ram and thus raises the cage. Since the weight of the ram and cage forms a large proportion of the whole load to be lifted, this must be balanced for efficient working, while since the volume of water displaced by the ram diminishes as the lift rises, the effec tive weight of the ram, which is its own weight less that of the displaced water, increases. Various devices have been adopted to overcome this difficulty. One common in high-class work con sists of a balance cylinder, one type of which is shown in fig. 2.

Here pressure water is admitted to the interior of the hollow ram B. The cylinder D is in communication with an auxiliary low pressure supply through the pipe C, and a downward pressure on the annulus at E is thus produced, which, together with the weight of this ram, produces a pressure in the cylinder F sufficiently great to balance any required proportion of the weight of the lift ram and cage. The total pressure transmitted to the water in the cylinder F is then the sum of the weight of the ram B and of the pressures on the annulus E and on the ram B, the former taking care of the balancing and the latter lifting the load. A suitable area of lift ram being assigned, the external diameter of B is calculated so as to give the required intensity of pres sure in the cylinder F. The lift cylinder is supplied from F through the pipe G. On the downstroke of the lift, the ram B rises, the balance water is returned to its own supply tank and the only water rejected is that originally filling the high-pressure ram B. As the balance ram falls, the pressure on the annulus E increases, due to the increasing head to which it is sub jected, and this to a certain extent counter balances the difference in the effective weight of the lift ram.

The suspension type of lift is operated from a hydraulic ram having a tively short stroke. The requisite travel in the wire rope by which the cage is pended, is obtained by using a rope and pulley multiplying gear, termed a jigger. The weight of the cage may be balanced by hanging weights, the varying immersion of the ram in this case being unimportant. In the balanced lift shown in fig. 2 two wire ropes are employed for lifting and two for carrying weights which partly counterbalance the cage. As the cage of such a lift rises, a portion of the weight of the suspending rope is ferred to the plunger side of the supporting pulley, and the tive weight transferred to the plunger consequently varies throughout the whole of its stroke. Fig. 3 shows a method of compensating for this variation. Here a double balance-chain is suspended from the cage as shown, so that if R be the travel of the cage, the length of each chain is R-:- 2. Let m be the multi plying factor for the jigger ; TV the weight of the unbalanced portion of the cage ; w the weight of the suspending cable per foot run ; w' the weight of each balance chain per foot run.

Then with cage at bottom, the pull on plunger =mill?' +wR } Then with cage at top, the pull on plunger = m { 1 -- wR.

And for these to be equal, w' = w(i I) . For very heavy lift ing, such as is necessary in canal lifts, etc., where loads up to i,000 tons may be car ried on a single ram, the direct-acting lift is the only suitable type.

Hydraulic Cranes, Jacks, Etc.— Where high-pressure water is available it provides a most convenient means of operating power cranes, and in its safety, adaptability to suit varying conditions, and steadiness of operation, offers some advantages over its chief rival, electricity. Such cranes are usually operated by hy draulic jiggers, the various operations of lifting, racking and slewing often being performed by separate rams and cylinders, each regulated by its own separate valve. Where the load to be lifted may vary within wide limits, some device usually is adopted to economize water at light loads. In small cranes, for loads up to about two tons, a differential or telescopic ram may be used, the smaller working inside the larger, which itself works in the pressure cylinder. For light loads the larger is held stationary by locking gear, the smaller ram then doing the lifting. For heavy loads the two rams work together as one.

Jib luffing cranes are used for dockside work. The jib has an extended end to which are attached the counterbalance weights and tie rods. The lower ends of the tie rods are attached to a travelling crosshead actuated by the rams of the luffing cylinders and also carry a compensating pulley. The lifting rope or chain passes over this pulley, with the result that when the jib is lulled inwards the hoisting rope is paid out to compensate for the rise at the point of the jib. By adjusting suit ably the stroke of the luffing ram and the inclination of the rods the level of the lift ing hook may be maintained constant for all radial positions of the weight.

The hydraulic jack is used extensively for raising heavy weights for short dis tances. In principle it consists of a Bra mah press on a small scale, and one type of its construction is illustrated in fig. 4. Here the reciprocation of a hand lever pumps water from the cistern A, through the hollow plunger B, past the suction and delivery valves and into the space C below the lifting ram and raises the lat ter. Screws are provided for supplying the cistern A with water and for allowing of the inlet of air, while a lowering screw permits of the escape of pressure water from the space below the lifting ram into the supply cistern when it is desired to lower the load. The lifting ram is usually packed by means of a cup leather, and the pump plunger by means of a single leather ring.

Reference has already been made to the Bramah press. Its modifications, as applied to such work as cotton baling, boiler plate flanging and heavy forging are too numerous for detailed mention. In the production of heavy forgings from large steel in gots it is essential that every part of the ingot should be worked equally if the resultant forging is to be homogeneous in structure. Where a steam hammer is used the energy of the blow is largely absorbed in producing distortion of the outer layers, while the interior is practically unaffected. This disadvantage is over come by the use of the hydraulic forging press with its slow and powerful compression, and this is gradually supplanting the steam hammer for the production of very heavy forgings.

The hydraulic riveter provides another good illustration of the adaptability of the hydraulic machine to workshop processes.

Here the problem is to get a fairly large pressure of the rivet during the first por tion of the ram stroke, so as to form the rivet head and to clinch the plates, and a final larger pressure of the nature of an impact to cause the rivet to expand and fill its hole fully. The extent to which this is attained in the riveter will be evident from fig. 5, which represents a typical pres sure diagram taken from the cylinder of such a machine, supplied from an accumu lator under a pressure of 1,roolb. per sq.in.

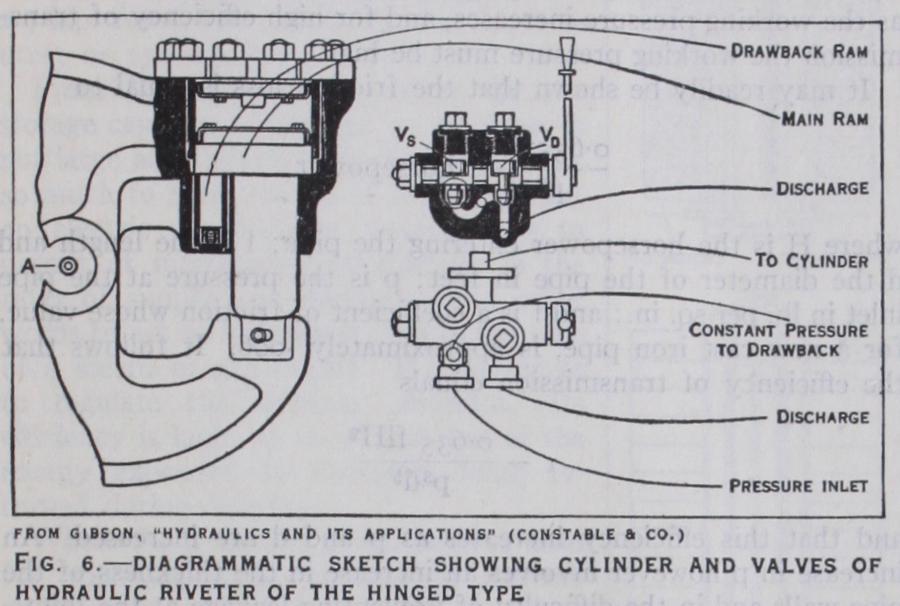

Here AB represents the idle part of the stroke during which the ram is being brought up to its work, BC the setting up of the rivet and the formation of the head, CD the clinching of the rivet and the closing of the plates, while the sudden stoppage of the heavy accumulator ram is responsible for a further rise in pressure DE above the accumulator pressure, which is depended upon to fill up the rivet hole. In fig. 6 a section of the cylinder and valves of a riveter of the hinged type is shown. Here the hydraulic ram acts on one end of an arm pivoted near the centre at A, and carrying the riveting head at the other end. Water is admitted to or discharged from the ram cylinder by the arrangement of valves shown. Thus a quarter-turn of the regulating lever raises the valve V. and puts the cylinder into communication with the pressure supply. On the completion of the working stroke a half turn in the opposite direction closes the valve V. and opens valve putting the cylinder into communication with the discharge passages. The main ram is drawn back on its idle stroke by means of a special drawback ram which is always exposed to supply pressure. The method of packing the rams and the gen eral construction are indicated in the figure.

Hydraulic Lock-gate Machinery.

In many modern docks the lock gates or caissons are operated by hydraulic machinery. In the Royal Edward Dock at Avonmouth, for example, each leaf of the entrance lock gates is operated by a direct-acting hydraulic cylinder with piston and rod, the stroke being r eft. gin. The sluice gates, 54in. diam., in connection with these caissons are also operated by direct-acting hydraulic rams working under a pressure of 7501b. per sq.in.

The Johnson Valve.

A type of valve which is being used to an increasing degree in large hydro-electric power installations is illustrated in fig. 7. A hollow central cylinder mounted in the centre of an enlargement in the pipe line and attached to the wall by radial ribs, carries a hollow differential plunger capable of axial movement in the cylinder. The projecting portion of this plunger forms the valve. The two chambers A and B can be put into communication either with the high pressure supply or with the atmosphere through small pipes with appropriate regulating valves. To close the main valve, pressure water is admitted to the chamber A, and B is allowed to discharge freely. The valve is then forced over to the right until it comes into contact with its seat. To open the valve the operation is reversed. When open, the water flows through the annular space between the valve and the pipe wall. This gives a waterway with no sudden changes of section or direc tion. Valves of this type are in use up to i8ft. in diameter.

Hydraulic Engine; Hydraulic Capstans.

Where a supply of high pressure water is available and where rotary motion at a moderate speed is desired, the reciprocating piston engine has certain advantages for small powers, particularly where it is able to work at or near full load and where the speed variation may be excessive, as occurs, for example, in the working of a capstan.As usually fitted to a capstan three single acting cylinders fitted with trunk pistons are fixed radially to an external casing, the three connecting rods working on a single crank pin. Each cylinder is fitted with a single inlet and outlet port, the opening of this to supply and exhaust being regulated by a rotary valve. This rotates along with the crank shaft and carries passages connecting with the pressure supply and the exhaust which are presented in turn before the port of each cylinder. The water-supply is regulated by means of a treadle which operates the admission valve.

Hydraulic Transmission

Gear.—Several schemes for trans mitting the torque developed at the crankshaft of a motor-car engine to the driving wheels by hydraulic means are now on the market. By the use of such a device shocks due to changing gear are avoided, while the ratio of the speeds of the driving and driven shafts may be regulated with a much greater degree of flexibility than is possible with a mechanical drive. All these devices are broadly the same in principle. The engine drives a series of pumps mounted radially around the central shaft, and these deliver the operating fluid, usually oil, under pressure to a series of fixed radial cylinders whose pistons are connected to the transmission shaft. The radius of the crank on to which these pistons drive can be varied, and since, at a given engine speed, the volume of fluid delivered by the pumps is constant, the ratio of the number of revolutions of the engine shaft and of the transmission shaft is in direct proportion to the capac ity of the pumps and of the driv ing cylinders with the crank ra dius in use at the moment. A number of gears of this type is described in the Proceedings (1921) of the Inst. Mechanical Engineers (p. 843).

The Fottinger hydraulic trans mitter is a combination of cen trifugal pump and turbine form ing a reduction gear through which the torque from a high speed steam turbine can be transmitted to a slow-speed steamship propeller. The prin ciple of the device is illustrated in fig. 8 b and c. The hydraulic impeller A mounted on the driving or primary shaft delivers water into the guide ring B, where it is deflected into the turbine wheel C mounted on the driven shaft. The water leaving C again enters the impeller A, either directly or after passing through a small guide wheel, so that it circulates again and again through the system. Fig. 8 b and c show diagrammatically the blading as arranged respectively for driving in the same and opposite direction to the primary shaft.

In practice a continual circulation of cold water is maintained through the transmitter by an auxiliary centrifugal pump. The efficiency is about 90 per cent.

Hydraulic Recoil Brake and Buffer Stop.

The necessity for some braking apparatus by which the kinetic energy of a heavy body, such as a moving train, or of a gun during recoil, might quickly and safely be absorbed without the tendency to rebound accompanying the use of spring buffers led to the inven tion of the hydraulic brake. In its simplest form this consists of a cylinder fitted with piston and rod and filled with some liquid, usually oil, water or glycerine. The two ends of the cylinder are connected, either by one or more small passages formed by holes in the body of the piston itself or by a by-pass pipe fitted with a spring-loaded valve or with a throttling valve by which the area may be adjusted. In its simplest form the brake is used extensively as a dashpot for damping the vibrations of governing mechanisms, etc. When used as a buffer stop, the body whose kinetic energy is to be absorbed forces in the piston rod and produces a flow of liquid from one side of the piston to the other at high velocity through the connecting orifices. The energy of the body is thus partly transformed into kinetic energy of the liquid, which is dis sipated in eddy formation and partly expended in overcoming the frictional resistances of the connecting passages, together with the mechanical friction of the brake. The whole of the energy is thus transformed ultimately into heat. Since the energy absorbed by the brake is equal to the mean resistance of the brake multi plied by the length of its stroke, it is evident that the pressure in the brake cylinder will have its least maximum value when this pressure, and therefore the resistance, is uniform throughout the stroke and when in consequence the pressure-displacement diagram forms a rectangle. The brake is therefore preferably designed so as to give as nearly as possible uniform resistance; and since the resistance varies as the square of the velocity of the liquid through the connecting orifices, while the velocity of the moving body and therefore of the piston, varies from a maximum at the instant of impact to zero at the end of the stroke, it is necessary either to make the connecting passages of diminishing area towards the end of the stroke, so that the velocity of efflux may remain constant, or to discharge from one side of the piston to the other through a spring loaded valve set to open at the required pressure. The former method is commonly used. The area of the connecting passage may be varied by forming it as a circular orifice through the piston and allowing this to work over a taper circular spindle fixed longitudinally in the cylinder, the available passage area varying with the diameter of the spindle. In an alternative arrangement, two rectangular slots are cut in the piston body and work over two longitudinal strips which are fixed to the interior cylinder walls and vary in radial depth from end to end.A similar device is used for absorbing the energy of recoil of large guns. The principle of one such recoil cylinder is shown in fig. 9. The liquid, escaping from left to right through the valve V, as the plunger is forced from right to left by the recoiling gun barrel, passes through the annular passage 0, whose area depends on the position of the piston relative to the central taper spindle T. The piston is returned by springs, whose action is buffered near the end of the stroke by the resistance to the flow of liquid from the space S through the holes at D. As a liquid for use in recoil cylinders, castor oil or rangoon oil is good and keeps the leathers in condition. A mixture of four parts of glycerine to one of water is also good, as is a mixture of methylated spirits 66%, water 31 %, mineral oil 3%, with 25 grains of carbonate of soda per gallon.

Hydraulic Dynamometer.—This, a device for measuring and absorbing the energy developed by a prime mover at a rotating shaft, was invented by William Froude and modified by Professor Osborne Reynolds. It consists of a rotating disk mounted on the power shaft and carrying on its outer faces a series of narrow pockets. These are semicircular in section, their plane is inclined at 45° to the axis of the shaft and they face forwards in the direction of motion. An outer casing mounted on ball-bearings surrounds the rotator. This casing carries a double set of pockets similar to those on the disk, in the same planes but facing in the opposite direction. Water is admitted to the casing and enter ing the pockets in the disk is thrown outwards and forwards by centrifugal force into the pockets in the casing. These guide it backwards and return it into the pockets in the disk and so on.

In this way a series of vortices is formed and the resistance to the change of momentum which takes place at each reversal of direc tion of the streams of water produces a braking effect on the disk and a tendency to rotation of the outer casing of the same amount. This is counteracted and measured by means of weights suspended from a horizontal lever attached to the casing. The resistance of the dynamometer can be regulated by varying the amount of water in the casing. In one modern form of the Froude dynamometer the casing is always full of water and the resistance is regulated by a sliding sluice plate fitted between the fixed and rotating pockets which cuts more or less of their periphery out of action. (For bibliography see HYDRAULICS.) (A. H. G.)