Hydrogenation

HYDROGENATION. The treatment of a substance with hydrogen so that this combines directly with the substance treated. The term has, however, developed a more technical and restricted sense. It is now generally used to mean the treatment of an "unsaturated" organic compound with hydrogen, so as to convert it by direct addition to a "saturated" compound. (See CHEMISTRY : Organic.) Thus, from ethylene, ethane is obtained: CH, Free hydrogen in the absence of a catalyst is too inert to take part in such a reaction. In the nascent state hydrogen reacts with certain easily reducible compounds; for instance, a ketone may be reduced to a secondary alcohol or a nitro-compound to an amine in this way. But the great increase in the number of known hy drogenation reactions during the present century is almost entirely due to the work of Sabatier and Senderens, Paal, Skita and others on the hydrogen-activating powers of nickel, cobalt, iron, cop per and the whole platinum group. (See CATALYSIS.) Catalytic hydrogenation has provided an easy method of pre paring many difficultly accessible substances, and several technical processes of considerable importance depend on it. (See CA TALYSIS.) The most important of these is probably the hardening of oils, whereby a liquid, chemically unsaturated oil is converted, by the introduction of hydrogen, into a solid fat suitable for use in the soap, candle or edible fat industries. To a lesser degree naphthalene, phenol and ben zene are hydrogenated commer cially to liquid products which are important solvents ; and various terpene derivatives, nota bly menthol, are produced tech nically by catalytic hydrogena tion. If the substance to be treated is a gas or vapour at the temperature employed, a mix ture of the substance with excess of hydrogen is passed over the catalyst contained in a tube or distilling flask as shown in fig. 1.

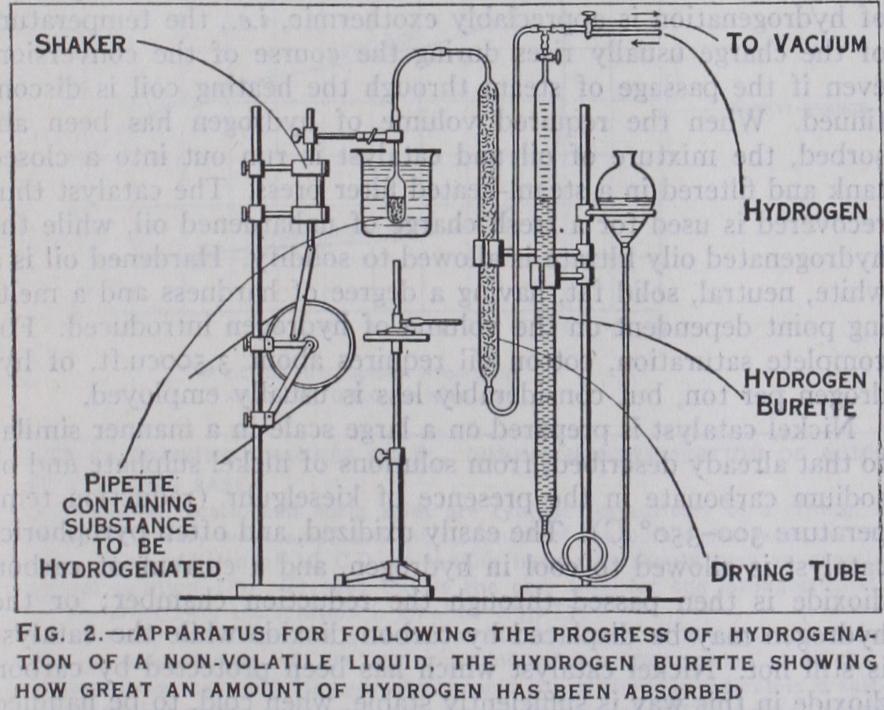

For the treatment of a non volatile liquid, the simplest pro cedure is to bubble a current of hydrogen through the liquid mixed with a finely divided catalyst and contained in a distilling flask, which is heated in an oil-bath. This method is, however, wasteful, and it is often more convenient for non-volatile as well as for volatile liquids to use some form of shaker in which the volume of hydrogen absorbed can be read off, and the progress of the reaction thus followed. A laboratory apparatus of this type is shown in fig. 2. For some hydrogenations the process is pref erably carried . out under pressure. In this case an all-metal apparatus has to be employed.

Scope of Reaction.

The scope of the reaction is indicated by the following typical conversions: — (a) Olefinic or ethylenic compounds are hydrogenated to the corresponding saturated or paraffinoid derivatives ; thus propylene is reduced to propane : : (b) Acetylenic compounds are very easily saturated with hydro gen; indeed, in the case of acetylene itself, the reaction is suffi ciently violent, if carried out in the gas phase, to cause consider able decomposition.

(c) Aromatic compounds are especially amenable to catalytic hydrogenation. Hexahydrobenzene is very difficult to prepare by other methods, yet Sabatier and Senderens found that it was readily formed on leading a mixture of benzene vapour and hydrogen over a nickel catalyst at 250° C; and it may also be obtained by shaking liquid benzene with hydrogen, in the pres ence of platinum or palladium. Naphthalene reacts similarly and is converted successively into tetrahydro- and decahydro-naphtha lenes ; and the reaction is general, as, for instance, hexahydro phenol (cyclohexanol) is obtained by the treatment of phenol. In hydrogenating ring compounds in the liquid phase, an increased pressure is of great advantage, especially if a nickel or other base-metal catalyst is used.

(d) Various unsaturated linkages, in addition to those between carbon atoms, are easily hydrogenated catalytically. From cya nides or isocyanides (R•C : N or R•N :C) primary or secondary amines or R•NH•CH3) are produced either by dis tillation with hydrogen over nickel or copper at 18o-200° C, or by agitating in a liquid or dissolved form in the presence of a catalyst of the platinum group. The azo-group, —N :N—, is re duced to a hydrazo-group, —NH•NH— ; thus azobenzene, on be ing shaken in alcoholic solution with hydrogen and a platinum catalyst, is quickly reduced to hydrazobenzene, which passes more slowly into aniline. Other non-carbon linkages, including those in heterocyclic rings, behave similarly : quinoline is reduced to deca hydroquinoline by hydrogenation under pressure.

(e) The above reactions are processes of simple saturation. A recent process of a different type, but of great technical im portance, which has been developed independently by Patart in France and by the Badische Anilin Fabrik in Germany, is the re duction of carbon monoxide to methyl alcohol (q.v.). (See