Hydroplane

HYDROPLANE. The hydroplane is so different from any other boat that it requires separate explanation.

Everyone has played "ducks and drakes" with a flat piece of stone on the seashore, and watched the projected object making a certain number of hops or ricochets over the surface of the water until the speed gets too low, and the stone sinks, being heavier than the water. It is obvious that if the stone were kept moving at full speed it would skim for ever. This is the principle of the hydroplane. The hydroplane is a lightly constructed boat with a comparatively flat bottom, and shaped to present an angle of attack to the water when driven at a high speed. The pressure of the water on the bottom raises the boat on the surface where the boat will stay as long as the pressure is maintained.

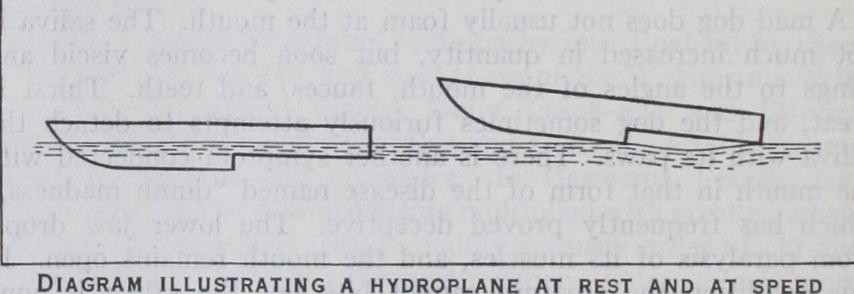

In the case of an ordinary boat the weight of the water dis placed by the boat equals the weight of the boat. That is to say, the volume of hole the boat makes in the water represents the weight of the boat. It is therefore seen that bodies heavier than water cannot float. When a boat travels at an ordinary speed it still makes a hole equal to its weight and the water has to be pushed aside to allow the boat to progress. At high speeds this causes great resistance. A body such as a hydroplane moving very fast stays at the top of the water without displacing its own weight and making only a very shallow hole in the water.

One may ask what is the advantage in building a boat to skim over the water. The answer simply is greatly increased speed. This being so, why not build all boats of hydroplane form. For certain motor launches of about 18 knots, the hydroplane prin ciple can be used ; under this speed, the inertia of the water is not great enough to produce much lifting effect, and then the hydroplane hull is bad as regards speed. In an ordinary boat practically all the power available is absorbed in wave making and skin friction, that is rubbing of the particles of water against the sides of the boat. A hydroplane is so designed that when a high speed is attained the normal pressure of the water on the hull shall have a large vertical component which raises the boat, the support being obtained from the reaction of water to which a downward velocity is imparted by the under surface of the hull. There results the continuous formation of a trough which de creases the wetted surface as a whole, but increases the pressure on the remaining wetted surface. In dealing with pressure, two totally different conditions are involved. First, floating where the hydro-dynamic force is practically nothing and the whole weight is supported by hydrostatic force due to immersion and, secondly, skimming where the hydrostatic effect is practically nil and all the support is due to the h:'dro-dynamic effects.

The credit for the first hydroplane form belongs to the late Rev. Charles Meade Ramus, Rector of Playden, Rye, Sussex, in about 187o. The want of a sufficiently light engine, however, pre vented his experiments getting beyond the model stage until about 35 years later. The Rev. Charles Ramus died in 1896 and thus had not the satisfaction of seeing the practical adoption of his proposals. When the petrol engine began to be used for racing boats much higher speeds were obtained by ordinary round-bottom boats, and the idea of the hydroplane principle again recurred to men's minds. The "Ricochet" hydroplane was probably the first practical boat of the type. The bottom was quite flat like a punt with a suitable inclined plane to make her skim. In others the bottom was quite flat in cross sections, but longitudinally was shaped like a saw, so that there were a series of inclined planes. Most of these boats had serious objections as the flat bottom is a very weak structure, and unless the water was quite smooth, the pounding even of small waves produced serious strain on the boats and damage was often done. Sir John Thornycroft experi mented at an early date with both model and boats of single-step type and, as long ago as 1877, took out patents for boats designed to skim. Thornycroft's experiments in the early steam days were with boats of quite flat bottom, with a single step, and arranged so that a hollow bottom should support the boat on a cushion of air. This latter method has attained prominence in America under the name of the "Sea Sled." In about 1910 Thornycroft made a very distinct advance by making the hull of a round or barrel form and the plane was built on, and a chine or angle piece was constructed on the bow of the boat. By this means the bow wave could not rise, but was thrown down laterally, concave sections were introduced below the bow portion which became flatter and re-curved as they approached the step.

Another type of hydroplane was introduced by W. H. Fauber. This type resembles an ordinary boat above the water but the under water portion is of a hollow vee form which becomes pro gressively flatter aft. A series of steps forming a number of in clined planes are built on the bottom of the hull. The single step form is a type that has been universally developed. Either plane can be arranged to carry all the weight, the other acting as a balancing plane. A large number of the fastest hydroplanes in America carry most of the weight on the after plane or, again, the weights may be distributed over the two planes, like the "Miranda" type, evolved by Thornycroft. Another type of hydro plane is the stepless. This type has developed rapidly during the past few years. The hull above the water resembles an ordinary boat but the under water sections are of a vee form, the deeper part being at the keel, the sections becoming flatter aft.