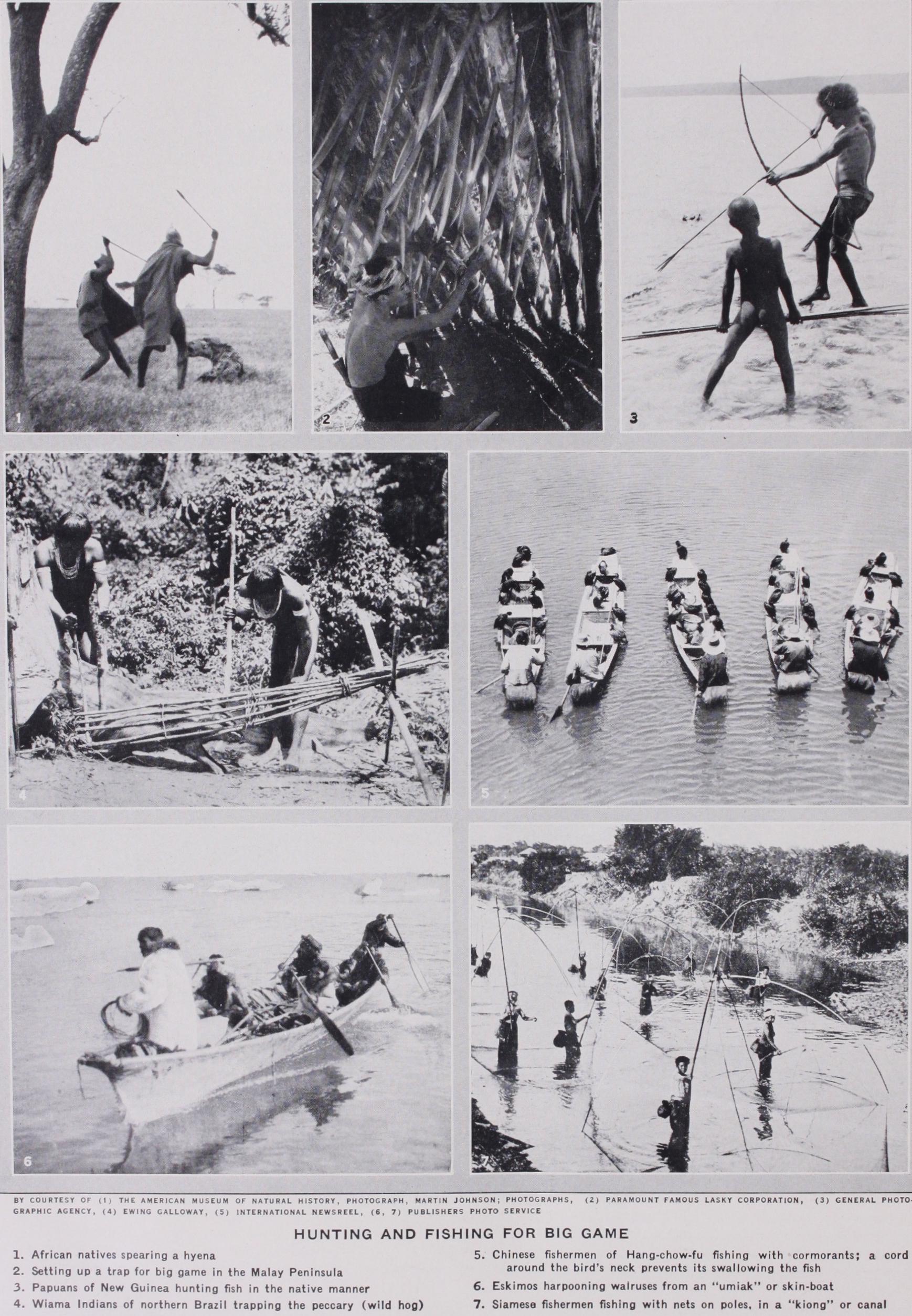

Primitive Hunting and Fishing

HUNTING AND FISHING, PRIMITIVE. Archaeologi cal evidence and observations on the most backward peoples of the present day show an appreciation of animal food, and, in the case of existing hunters, considerable ingenuity in methods of capturing it. The earliest teeth suggest that man was omnivorous, eating flesh as well as vegetable products; primitive hearths contain ani mal bones intentionally smashed with stones for the extraction of the marrow ; and stone weapons have been found embedded in vertebra and skull of Palaeolithic reindeer (Dordogne) and Neo lithic ox (Cambridge). The cave paintings of western Europe are presumed to represent the efforts of hunters to obtain success in their hunting by magical means. Primitive man everywhere de pended on hunting and fishing for his supply of animal food. Later, hunting is accessory to agriculture, provides variety in the veg etable diet, and survives as sport or recreation ; or is required to protect flocks and herds against predatory beasts. Primitive agriculture is often the work of the women while the men are hunters. But where nature is sufficiently lavish in vegetable food, or where land mammals are comparatively few and small, hunting is of secondary importance to fishing, and fishing to horticulture. It is of least importance to purely pastoral people among whom, except for defence or sport, it is often entirely disregarded, while for many of them all meat save that from their herds is tabu.

At the present day hunting peoples, together with the game on which they depend, are being encroached upon and crowded out by pastoral or agricultural peoples. When hunters can no longer shift their hunting grounds, when game diminishes or disappears, they must find some other food supply or die. As a purely hunting group they cease to exist. They may be actually exterminated, like the Tasmanians, and, to a large extent, the Bushmen of South Africa ; they may be artificially protected and preserved, like the Amerinds of North America, and the Aus tralians ; they may survive with the help of agriculture, like many central African peoples; or augment their living by trade, like many of the Eskimo groups. But in their original state hunting peoples are now found only in unsettled districts, in areas too barren, remote, unhealthy or otherwise unattractive for settlers. In Africa the equatorial forest region preserves its pygmies and marginal Bantu hunters, the barren semi-desert of the Kalahari its scanty tribes of Bushmen, and sporadic groups of hunting peoples are found in isolated patches such as the Bauchi highlands of Nigeria and elsewhere. In the tundra region of Asia, animals are hunted as much for fur as for food, and the general use of fire arms raises the hunting above the primitive level ; but to the east, the Ainu in northern Yezo and the Kuriles still shoot with small bows and poisoned arrows and maintain themselves by fishing and hunting. In the south of the continent the forested and hilly parts of Ceylon shelter the Vedda, and the jungles of southern India contain tribes such as the Kadir of the Anaimalai hills and the Kurumba of the Nilgiris. Further to the east the isolated Anda man islands, the thick jungle of the Malay peninsula, and neigh bouring islands, and parts of the Philippines all contain primitive hunters and collectors, as do the open arid plains of Australia. In North America the Eskimo, a typical hunting and fishing people, fringe the north coast and its islands and the easternmost end of Asia ; on the north-west coast the Salish, Nootka, Tshimshian and other tribes, live in one of the best hunting grounds of the world, between the mountains and the sea. The caribou and other deer in the tundra and northern plains, and bison in incredible herds in the heart of the continent (from the upper waters of the Saskatchewan to the Gulf of Mexico) maintained hunting tribes until the coming of the whites. In South America the river basins of the Guianas and the Amazon are still occupied by little-known hunting tribes, usually partly dependent on cassava made from manioc. To the south, from the interior of the Argentine to the Horn is more or less open country where the guanaco (wild llama) was abundant, and, with smaller game and fish, supported nomadic hunters. In this area the Spaniards introduced cattle, which ran wild over the plains, and wild horses, to be trained to follow in pursuit. Some of the Gran Chaco hunters cultivated a little maize but this was unknown to the Patagonians, and in the extreme south the Fuegians, like the Eskimo, depend more on sea produce than on land.

Except in cases of co-operative hunting, as among the Amerinds and in the Congo region, a hunting group is small in numbers. Its first demand is for space. The land must be unoccupied and the game free from disturbance, for a hunting community needs one to ten miles, and in barren areas up to 500 miles, per head of the population. Families are small, children few, and many succumb to the inevitable hardships of the life. The group wanders within a recognized area, camping at convenient spots, but no settled life is possible.