Violin

strings, instruments, notes, makers and belly

VIOLIN, the smallest and highest-pitched of one of the most important families of stringed musical instruments, to which it gives its name. It consists essentially of a resonant box of peculiar form, over which four strings of different thicknesses are stretched across a bridge standing on the box in such a way that the tension of the strings can be adjusted by means of revolving pegs, to which they are severally attached at one end. The strings are tuned, by means of the pegs, in fifths, from the second or A string, which is tuned to a fundamental note of about 435 vibrations per second at the modern normal pitch, thus giving as the four open notes. To produce other notes of the scale the length of the strings is varied by "stopping" them—i.e., pressing them down with the fingers—on a finger-board, attached to a "neck" at the end of which is the "head" in which the pegs are inserted. The strings are set in vibration by drawing across them a bow strung with horse-hair, which is rosined to increase adhesion.

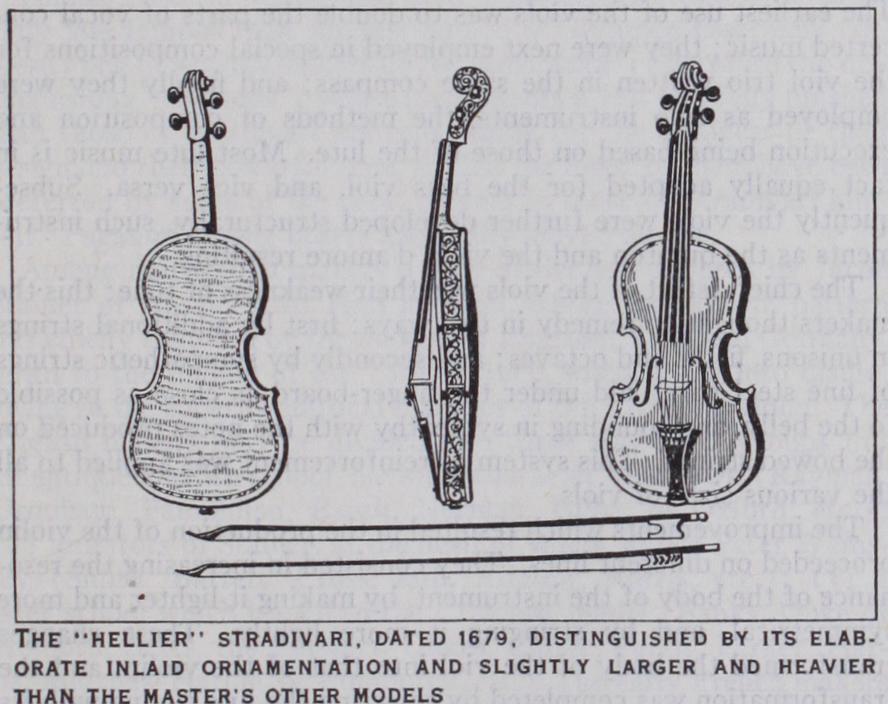

The characteristic features which, in combination, distinguish the violin (including in that family name its larger brethren the viola and violoncello, and in a lesser degree the double-bass) from other stringed instruments are the restriction of the strings to f our, and their tuning in fifths; the peculiar form of the body, or reso• nating chamber, especially the fully moulded back as well as front, or belly; the shallow sides or "ribs" bent into characteristic curves ; the acute angles of the corners where the curves of the ends and middle "bouts" or waist ribs meet ; and the position and shape of the sound-holes, cut in the belly. By a gradual process of development in all these particulars the modern violin was evolved from earlier bowed instruments, and attained its highest perfection at the hands of the great Italian makers in the 16th, 17th and early 18th centuries, since which time, although many experiments have been made, no material improvement has been effected upon the form and mode of construction then adopted.

The following are the exact principal dimensions of a very fine specimen of Stradivari's work, which has been preserved in per fect condition since the latter end of the 17th century Length of body 14in. full.

Width across top 614in. bare.

Width across bottom Height of sides (top) in.

Height of sides (bottom) The back is in one piece, supplemented a little in width at the lower part, after a common practice of the great makers, and is cut from very handsome wood ; the ribs are of the same wood, while the belly is formed of two pieces of soft pine of rather fine and beautifully even grain. The sound-holes, cut with perfect pre cision, exhibit much grace and freedom of design. The scroll, which is very characteristic of the maker's style and beautifully modelled, harmonizes admirably with the general modelling of the instrument. The model is flatter than in violins of the earlier period, and the design bold, while displaying all Stradivari's mi croscopic perfection of workmanship. The whole is coated with a very fine orange-red-brown varnish, untouched since it left the maker's hand in 169o, and the only respects in which the instru ment has been altered since that date are in the fitting of the longer neck and stronger bass-bar necessitated by the increased compass and raised pitch of modern violin music.

Acoustic acoustics of the violin are ex tremely complex. Certainly so far as the elementary principles which govern its action are concerned, it follows sufficiently fa miliar laws (see SOUND). The different notes of the scale are pro duced by vibrating strings differing in weight and tension, and varying in length under the hand of the player. The vibrations of the strings are conveyed through the bridge to the body of the in strument, which fulfils the common function of a resonator in re inforcing the notes initiated by the strings. So far first principles carry us at once. But when we endeavour to elucidate in detail the causes of the peculiar character of tone of the violin family, the great range and variety in that character obtained in different instruments, the extent to which those qualities can be controlled by the bow of the player, and the mode in which they are influ enced by minute variations in almost every component part of the instrument, we find ourselves faced by a series of problems which have so far defied any but very partial solution.