Visual Sensation

hue, stimulus, stimuli, saturation and intensity

When the stimulus is heterogeneous, the hue and saturation are determined by rather complex principles, known as the laws of colour-mixture. The simplest case is that of two-component mixtures, involving pairs of homogeneous stimuli. If the wave lengths and relative intensities are properly chosen, the result can be an achromatic colour or white, and in this case the stimuli (and the colours which they would separately evoke in isolation) are said to be complementary. If the wave-lengths of such com plementary stimuli are held constant, and the intensities are varied from those required to yield white, a hue appears which is normal to the stimulus that is in excess, the saturation increasing with augmented unbalance. When the wave-lengths depart from those of complementary stimuli, the hue is intermediate, on the shortest arc of the hue cycle, between the hues normal to the two stimuli. The exact position of the hue on the arc is determined by the balance of intensities, naturally being near to that normal to the component which is intensively predominant, in proportion to the degree of predominance. The saturation is greater the more the two stimuli depart from the complementary relationship, either as regards wave-lengths or intensities.

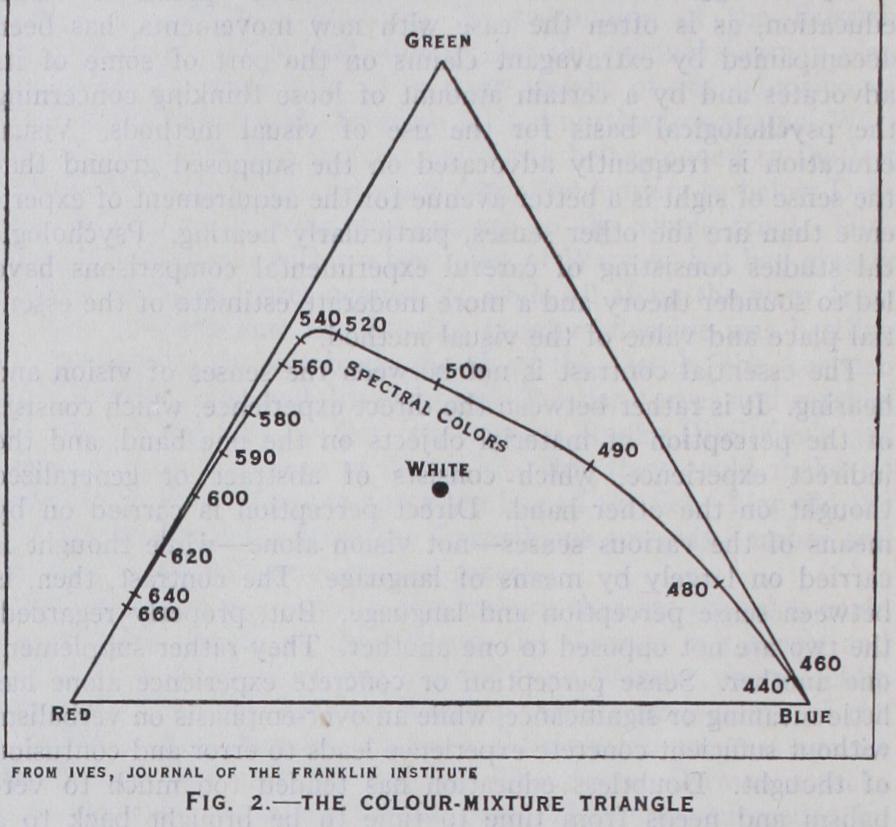

One of the most interesting cases of two-component mixture is that which involves the two extremes of the visible spectrum, yielding a series of purples, of which there are approximately 20, determined by the intensity ratios of the two components. The purples furnish the complementaries for colours or stimuli in the middle region of the spectrum, which find no homogeneous complementaries. The three-component system, thus generated, consisting of two extreme spectral stimuli and a mid-spectral stim ulus, provides the most important of all cases of colour-mixture. It is found that variation of the intensity proportions of such stim uli, of fixed wave-lengths, permits the matching of all possible hues at a wide variety of saturations. This fact underlies the technique of three-colour reproduction and analysis. The laws which are in volved are most simply represented by means of a colour-mixture triangle, such as is shown in fig 2, where the three primary com ponents are symbolized by the vertices of the equilateral figure.

The units of measurement in this triangle are so chosen that equal quantities of the three primaries yield white. The bril liance value of the blue or violet, thus required, is only about i % of that of the red or green. The composition of any colour, in these terms, is found by locating it within the triangle and then dropping perpendiculars to each of the three sides. The length of the perpendicular opposite each primary indicates the pro portion of the latter which is involved. The consequences of mixing any two colours can be determined, in this system, by drawing a straight line between the points which represent them, and then finding the centre of gravity of the line, treating the mixture intensities of the components as masses. Mixtures of any number of components can be handled in this way by suc cessive combinations in pairs. Thus the triangle provides a uni versal method for dealing with the hue and saturation aspects of stimulus mixtures. The colours of the spectrum can be repre sented by a linear locus, and in order that this should fall inside rather than outside of the triangle, the latter is ordinarily recon structed on the basis of an ideal, supersaturated, green primary.

Hue and saturation also vary with the absolute intensity of the stimulus. At both low and extremely high intensities there is a loss of saturation, which may be complete. There is also a change of hue, with increasing intensity, such that all colours, except primary red and green, tend to become more yellowish or bluish, according as they lie on the yellow or the blue side of red or green, respectively. This is known as the Bezold-Brticke effect.

The relations of colour to retinal conditions can best be dis cussed in connection with spatial and temporal effects, although in only a few cases are we sure that such effects are retinally rather than cerebrally determined. Among temporal phenomena, we may mention those of adaptation, according to which con tinued exposure to any stimulus brings about changes in sensi tivity which tend to neutralize the characteristic effect of the stimulus. Brilliance adaptation is apparently of two kinds, sco topic, involving a changing ratio between rod and cone vision, and photopic, depending upon changes within the cone system per se. The latter may be selective, as regards hue and saturation, reducing the latter and rendering the retinal system temporarily more sensitive to the complementary. Local alterations in sensi tivity yield so-called negative and complementary after-images which can be used to demonstrate the rate at which recovery, or counter-adaptation takes place.

Other temporal effects include positive after-images, which appear to represent a continuation of the original excitation pro cess for a short time after the removal of a stimulus; rhythmic alternations between positive and negative conditions, giving rise to such phenomena as Charpentier's bands and "recurrent vision"; and fusion, with intermittent stimuli presented at a sufficiently high rate, resting upon the so-called "persistence of vision." Spatial dependencies are represented by the variation of hue and saturation with the position of the stimulus on the retina, the partial dependence of all of the colour attributes upon the size of the retinal image, and by the phenomena of contrast. In general, chromatic differentiation is at a maximum in the centre of the visual field and falls off towards the periphery in accordance with the same qualitative law which characterizes the Bezold Brucke effect (vide supra). Brilliance shows a maximum in the centre of the field under photopic conditions, but a powerful mini mum in the same position under scotopic adaptation. This is attributable to the absence of rods in the retinal centre or "fovea." Intensity thresholds for hue and brilliance are raised by decreasing the retinal size of the stimulus below a certain value, and at very small sizes the threshold is determined by the total energy striking the retina, regardless of its distribution between intensity and area. Contrast (q.v.) involves a change in the colour evoked by a given stimulus, because of the simultane ous action of another stimulus (or condition) on an adjoining visual area. The change is in the direction of the opposite of the contrast-inducing colour, being a darkening effect when the latter is bright, and a shift towards the complementary of the latter when it is of chromatic quality.