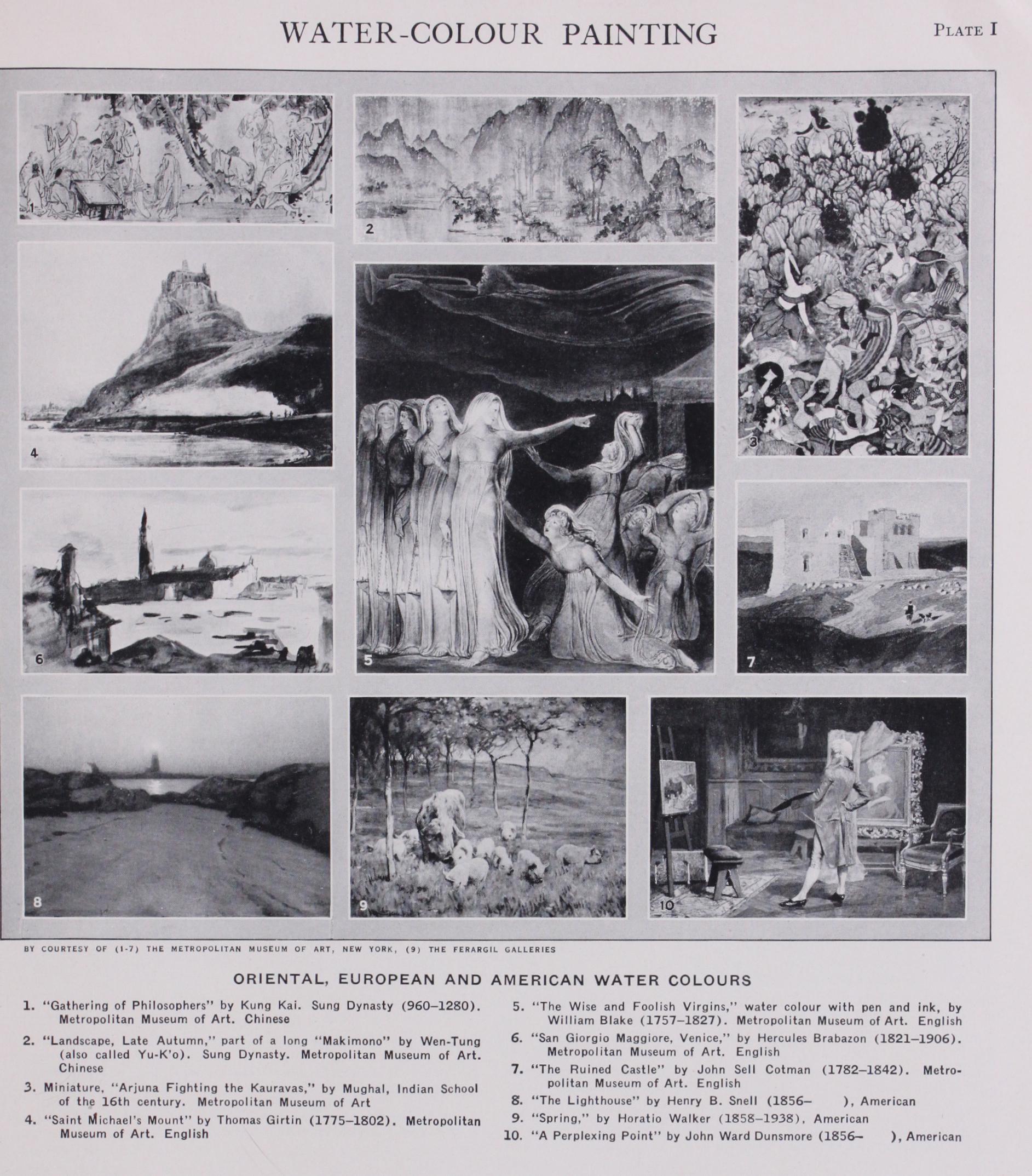

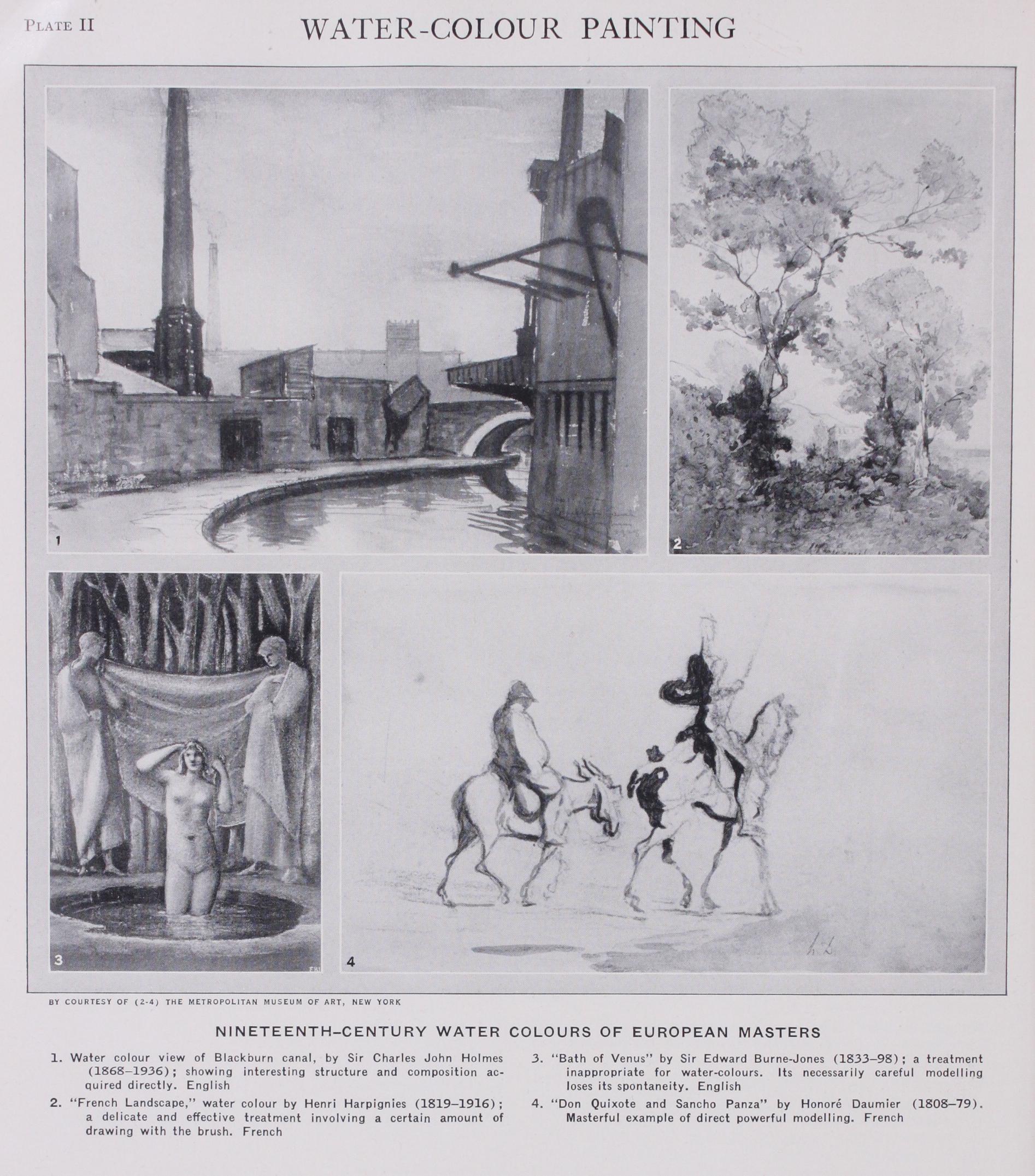

Water-Colour Painting

art, century, colour, fresco and design

Painting began in the 5th century, brought by Nawrin from China. By the middle of the 6th century a real art of painting, of which Buddhism was the main theme, had begun. The art was thereafter carried out under Korean and Chinese immigrants. Toward the end of the 9th century, two exotic styles of painting flourished, and on these a native style had been founded which featured landscape of a romantic kind, animal life, trees, flowers and designs representing legends of olden times. The exotic Buddhist style brought a change. Of Indian origin or influence, it was brilliant and decorative, with a lavish use of gold, and con fined to representations of sacred personages and places. The principal painters of this period, extending into the succeeding centuries, were of the Kose, Takuma and Kasuga lines, descending from Kanaoka, Takuma Tameuji, and Fujiwara respectively. Last and greatest was Meicho, or Cho Densu, who died in 1427.

The beginning of the iith century shows adaptations of Chinese canons to motives selected from poetry, court life, and legends of Old Japan. This art was characterized by a lightly touched outline and tinted with flat and bright body-colour. Verdigris-green domi nated the schemes. Important names are Fujiwara no Motomitsu (1 I th century), Nobuzane and Tsunetaka (13th century), Mit sunobu (15th and 16th centuries), Sishu (1421-1509), Shaun and Kano Masanobu (1424-152o), Mitsushige and MitsuOki (17th century).

A popular period began with the establishment of a school of art by Hishigawa Moronobu (1646-1713). He created a progres sive and trustworthy life about him, expanding his followers' artistic natures. After this came a development of realistic art, which compares in time with the European style. This manner has its importance in the great harm it did to Japanese art. It at tempted to reproduce nature and all forms exactly, combining European chiaroscuro and linear perspective with the Japanese style. Glass, tapestry and furniture suffered as well as pictures. Except for the existence of water-colour painting, the loss would have been still greater. (See JAPANESE ART.) Persian Artists.—During the 8th century, Turkistan princes sent into China for their artists and in the conventionalization of certain forms and flat treatment of figures, a trace of Chinese influence is discernible. The few surviving paintings of the Mongol period are in the Persian manuscripts of the "History of Ghenghis Khan and Family," and are the most important, dating back to A.D. 1314. Here the Mongol types and fashion of drapery are manifested. At Herat, the most famous of the Persian masters, Bihzad, who founded a National School of Painting, changed the course of the native art. Bihzad illustrated manuscripts of the two most famous poets, Sadi and Nizami. The Sultan, Mahmed, worked in Mirak's studio and Mirak, who was born A.D. 150o, was a pupil of Bihzad.

The most important contribution of Persian art, and to it the Indian is closely allied, is its charm of colour. As the school matures, it shows a weakening of design, becomes less coherent, and conventions become dominant ; vitality is lost and expres siveness of drawing is smothered. But the gem-like colour and

refined luxury give a marvellous atmosphere of sensuousness and beauty. Figure work was not done from living models. The painters recreated the entire scene in their mind and in putting colour on material suggested such detail only as was essential to the depicting of the tale. This lack of realism gave a splendid feeling of all-over pattern (see Plate I.—Persian Art ; Plate I., fig. 3—Water-Colour Painting). Chiaroscuro and modelling were not important in painting, and third dimension was sedulously avoided ; decorative effects in two dimensional space were aimed at. (See PERSIAN ART, PAINTING AND CALLIGRAPHY.) Indian Technique and Materials.—The earliest material used in painting was a red haematite which was mixed with an animal fat. The outlines were made with a pointed stick, brushes being of such poor quality that it was not possible to bring them to a point; they were probably made of vegetable fibre at first. White was obtained from an earth substance, possibly a clay or lime; black was obtained from dried astringent prune-like fruit.

Frescoes•—The Buddhist frescoes were painted over a roughly excavated wall, first prepared with a coating made of a mixture of clay, camel dung, and trap rock, to the thickness of to a inches. This surface was then coated with a thin layer of white plaster and the painter was ready to paint frescoes in water-colour. The method used is open to difference of opinion. True fresco was done on wet plaster. If a part of the design did not suit the artist, he had to cut out that section and apply a fresh coat of wet plaster. The other method (fresco secco) is a combination of fresco and tempera. The plaster ground is allowed to dry before painting. True fresco is favoured but much more difficult be cause a design cannot be changed except as mentioned above.

The Rajput painting was a mural in design but done on a small scale. Paper was used instead of a wall surface. The Mogul miniatures were painted on a paper composed of bamboo, jute and cotton. The surface was carefully rubbed smooth with a rounded agate. Later English painters took rough paper, painted their figures on it, but rubbed the surface smooth where the heads were to be. A fine texture was acquired in this way.

These various processes of clear colour, fresco, tempera and combined methods of water-colour and inks, paved the way for the development in southern and western Europe. Italy took what was best suited for its climate, tempera ; fresco for wall surfaces, and the mixed methods of tempera and ink for book illumination scrolls, and later for studies to be developed in larger oil painting, as oil became better understood during the Middle Ages. Water-colour slipped lower down the scale of artistic and popular appreciation. The return to active use of water colour now heralds a real awakening of art and promises tremen dous progress in the near future. Beauty of colour and dignity of design will strip the old ugliness of things from our every day lives and prevent the return of naturalistic abominations. (See INDIAN AND SINHALESE ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY.)