Wood-Carving

carved, carving, designs, wood and century

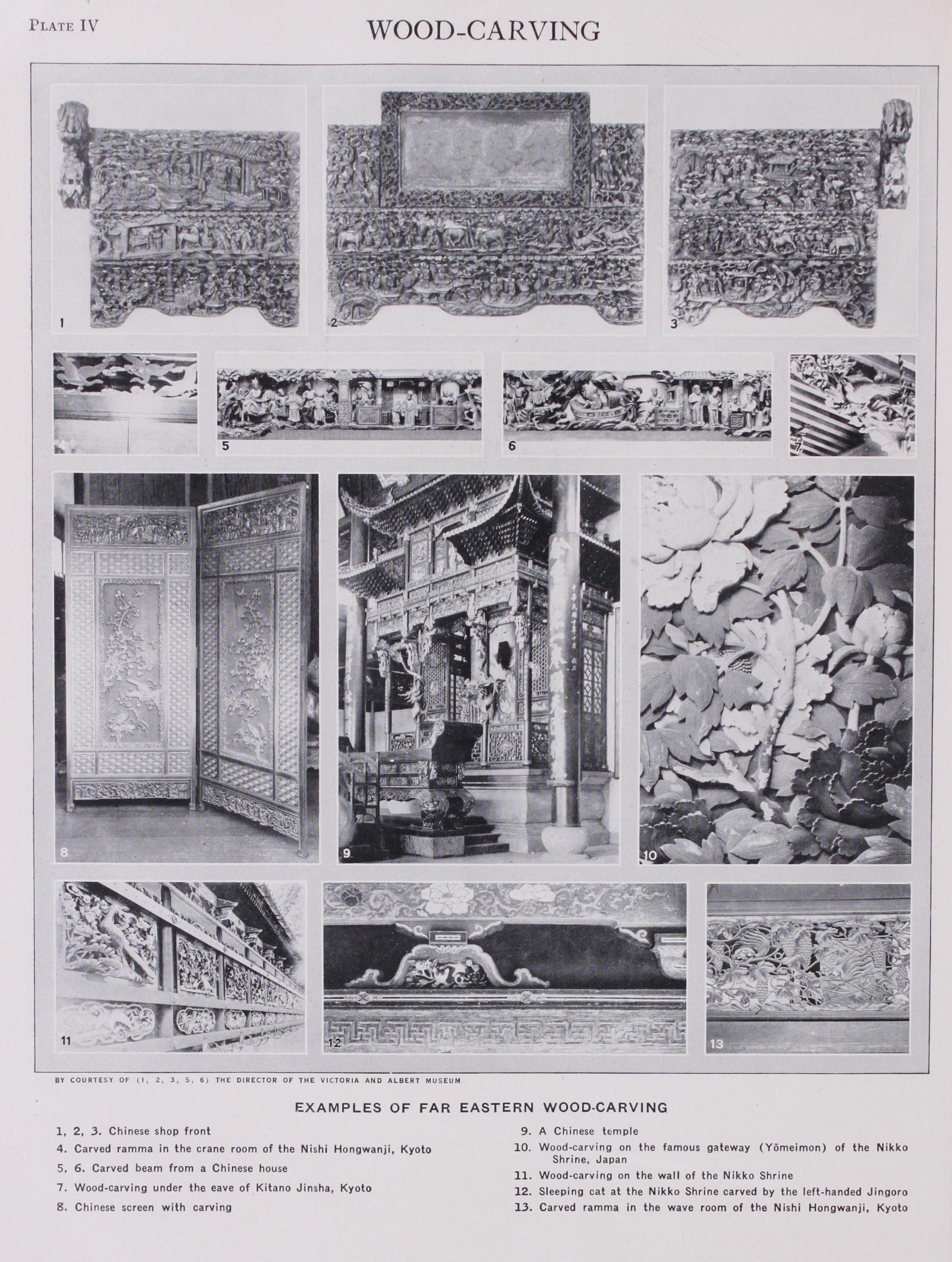

Artistic vitality characterizes even the highly conventionalized designs of the Japanese wood-carvers, but the bulk of the Chinese work reveals a sense of laborious and mechanical execution. On the whole, the Chinese wood-carvings are more effective as a design and ornament compared with the Japanese work, which, while the thing carved on is well decorated, carry a far less decorative value. The former aims more for the effect, while the latter pays much greater attention to the mode of execution and technical skill. The former covers the carving with paint or lacquer,while the latter delights in appreciating, whenever possible, the clear cut chisel marks in natural wood. Even the decorative panels in the temples and shrines which are coloured, show traces of the Japanese wood-carver's pleasure and satisfaction derived from the clear cuts of his chisel. There is a tendency in both for an effort to surmount formidable difficulties in design and execu tion, defying time and labour, with little regard for the artistic merit in the result achieved. (See INDIAN AND SINHALESE ART; INDONESIAN AND FURTHER INDIAN ART.) and their Treasures, Dept. of Interior, Japan ; F. T. Piggott, The Decorative Art of Japan (Iwo) ; S. W.

Bushell, Chinese Art (z904-1909) . HAR.) Such meagre fragments of woodwork as have come down to us from the nth and 12th centuries, tend to show that the woodworker was following the stoneworker in every particular, and that where he failed to be constructive, he had to call in the help of the metalworker to make his ware hold together. The stoneworker was paramount until about the 15th century. From that time onward it was the woodworker who became predomi nant. By that time he had found that wood should be treated in quite a different manner from stone, and, inspired by new ideas and new motives, he invented new methods for the construction and embellishment of his work. The wood-carver, then, no longer followed the patterns and designs of the stone-carver, but he made them for himself in a manner to suit the material and tools he worked with, in fact he began to influence the stoneworkers in such a way as sometimes to divert them from their intrinsic principles.

Early Period.—The earliest examples of wood-carving are some remnants of Scandinavian carving dating from the ninth and tenth centuries. They are carved framings of doorways made of thick planks of pinewood. They follow the same form of designs as are found on Celtic stone crosses, or in the elaborate initial letters of early illuminated manuscripts. This carving is in low relief, and it is always kept up to the surface of the ma terial out of which it is made. The designs are of interlacing stems sometimes foliated, and often terminating in a monster's head. Occasionally the stem is doubled and criss-crossed, and invariably the space which is decorated is so much filled with pattern as to leave scarcely any ground showing. An example of this kind of carving is shown in the reproduction of a Norwegian chair of the 9th or loth century. (P1. V., fig.

Of the Norman period in England only a few isolated pieces remain, and these are only enriched with a row of moulded arches, as in the railing at Compton church, Surrey, or the desks at Rochester, or the tomb at Pitchford church, Shropshire, which has also a shield carved in oak in each arch of the arcaded side of the tomb, supporting the carved wood effigy of Sir John Pitch ford, which was made at the very end of the Norman period. It may be conjectured that the characteristic feature of Norman wood-carving is the rounded surface of most of the foliated forms, which appear to have avoided hollows. The leaves were often a series of lobes with a V-shaped sinking round the edge. Even in the mouldings, beads or rounds preponderated over hollows, and in the grotesque beaked heads carved on the arches to many a doorway the surface treatment is generally a series of ribs or small rolls, rather than a succession of hollows or V cuts as was the case in Byzantine ornament. Sometimes the stems of the foliage were enriched by a small bead carved on either side of a rounded stem, as may be seen on the Prior's doorway at Ely cathedral.

Of the early English period which lasted roughly from 1190 to 1310—a little over loo years,—there is not a great deal of wood carving remaining, though there is sufficient to tell us what it was like, even in elaborate work, as in the stalls at Winchester cathe dral. These however were executed at the very end of the 13th century. They are carved with the utmost care and skilfulness but the work follows the idiosyncrasies of the stonemason and carver, inasmuch as it is cut out of solid blocks of oak and the forms and designs are identical with that of stonework. Some of the designs for foliage follow the typical early English forms, whilst others might be taken for the work of the next great divisional period of architecture which followed. The miserere seat from the Priory church at Christchurch, Hampshire is a good example of early English carving. (Pl. V., fig. 2.) Others may be found in Henry VII.'s Chapel at Westminster, and at Exeter.

In the traditional carvings of the 13th century the curves of the foliage are very simple. The leaves start from a fairly thick stem which is generally cut very square in section. Sometimes the curve of the stem is reversed as it nears the end of the spray, but more often than not it is one simple curve which quickens as it reaches the end of the leaf, and finally buries itself in a deep pocket in the centre lobe. The variations of this form of foliage are wonderful and beautiful in the extreme. The build ing where this form of carving may best be studied in England is Wells cathedral. Towards the end of the 13th century the wood workers were coming into greater prominence. There is an example of a groined roof with carved bosses at the junction of the ribs at Warmington, Northamptonshire, and of carved roof beams at Bradfield, Berkshire; and Rochester cathedral has a lean-to roof with moulded beams.