Woodcuts and Wood-Engraving

line, black, lines, woodcut and cut

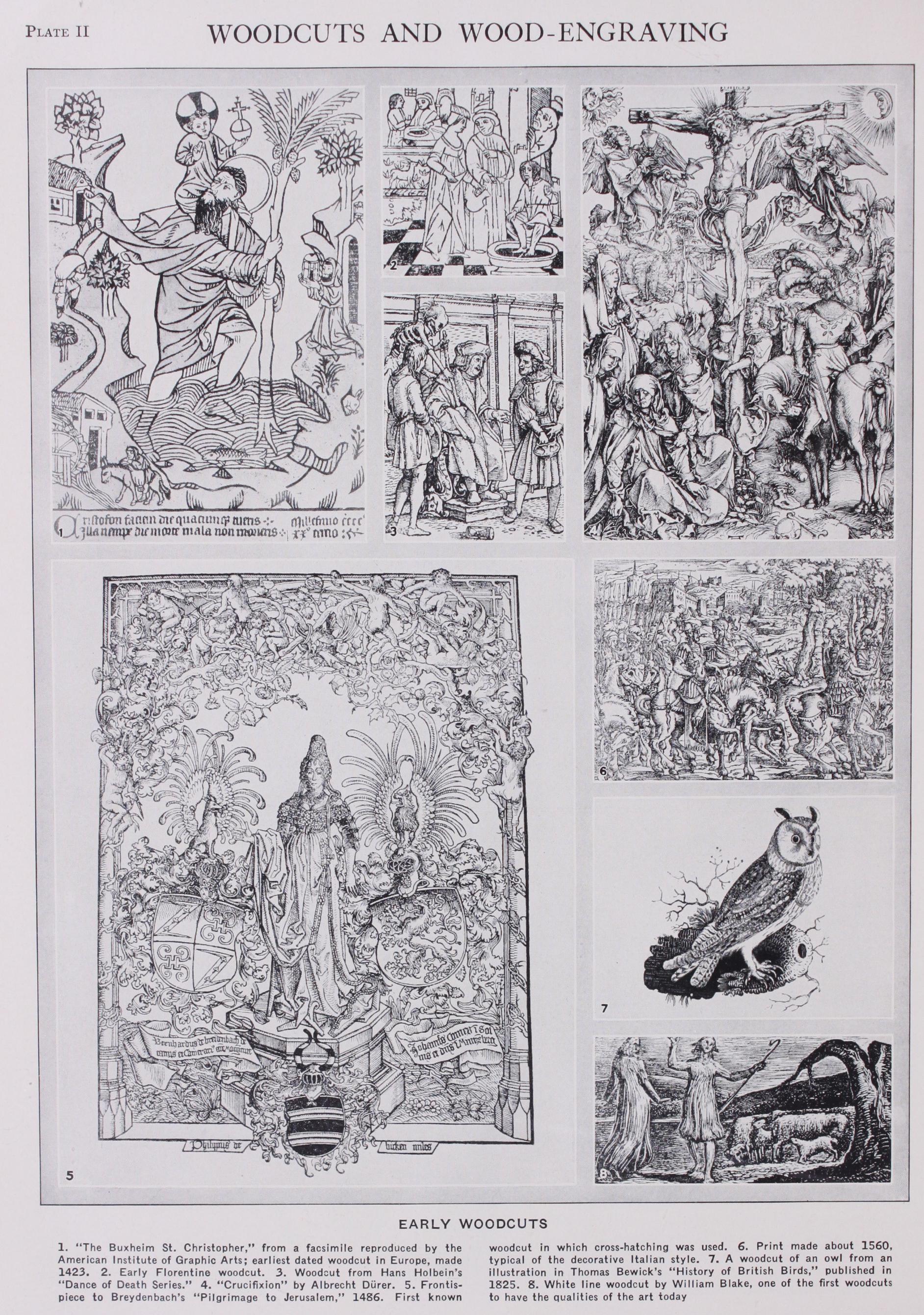

WOODCUTS AND WOOD-ENGRAVING. the woodcut is used as a direct expression of artists who themselves cut and print the block. During the greater part of its history the medium has been used quite differently. It has been a reproduc tive process; a craft rather than an art. Craftsmen have cut out of the block drawings made for the purpose by artists and then passed the block to other craftsmen for printing. This is comparable to our photo-engraving reproductive process—the dif ference being that the older method was done by hand whereas the present one is mechanical. In both cases the method was merely a means to an end and quite detached from the original concep tions of the artists involved. In making drawings for reproduction, either by woodcut or photo-engraving, artists are thinking in terms of ink or pencil lines on paper—not of lines which their hands are carving out of wood. A work so detached from its medium does not exploit the peculiar quality of that medium. It lacks unity and completeness. It loses force. For some ten centuries of its known history the woodcut, as a process, has been so handicapped. Only during the last thirty or forty years has it arrived at what might be called its full functioning maturity.

Technically speaking the woodcut is pictorial type. It prints pictures as type prints letters of the alphabet, by raised lines or areas that catch ink from a roller and deposit it on paper under moderate and more or less even pressure. This analogy roots in history as well as fact. The first printed letters were woodcut type carved into pictorial woodcut blocks in explanation of the picture. The first movable type was a cutting up of this block type in order to save labour by rearrangement and re-using. The woodcut raised line is the opposite of the intaglio, or sunken line, which is etched or engraved on copper. (See INTAGLIO.) In the print etched or engraved lines catch the light and cast minute shadows, thus giving a life or sparkle to the work that is impos sible with any other mediums. The woodcut gives a flat surface print, with an interplay of solid black and white, and a slightly varying texture and intensity that is quite unique.

The raised line of the woodcut is simply a part of the original untouched surface of a block or plank of wood; if no cutting away were done the print from this block would be solid black. Each

stroke of the tool removes a section of the ink-holding surface, thus preventing its printing and letting the white of the unprinted paper into the black of the printed. Like the world at dawn, the woodcut-picture actually emerges from blackness into light.

There are two kinds of woodcuts, the black line and the white line. The black line, or woodcut proper, is one for which a draw ing is made on the block and all spaces between lines gouged out or cut away. In other words a black line drawing is reproduced in approximate (but never complete) facsimile. The black lines are conscious lines. The white lines or spaces are leftovers which receive either secondary or no consideration per se. In the white line cut, or engraving, the reverse holds ; the white line that is gouged out will receive first attention, the black lines and spaces between, second. In the first case the artist conceives his draw ing as starting with white paper and growing towards black; in the second as emerging from black into light, as in actual fact it does. Both systems have their advantages but the second, or white line, being the natural method, because it makes a positive instead of a negative use of each gouge or cut, would seem to be the most logical.

Cutting the Block.

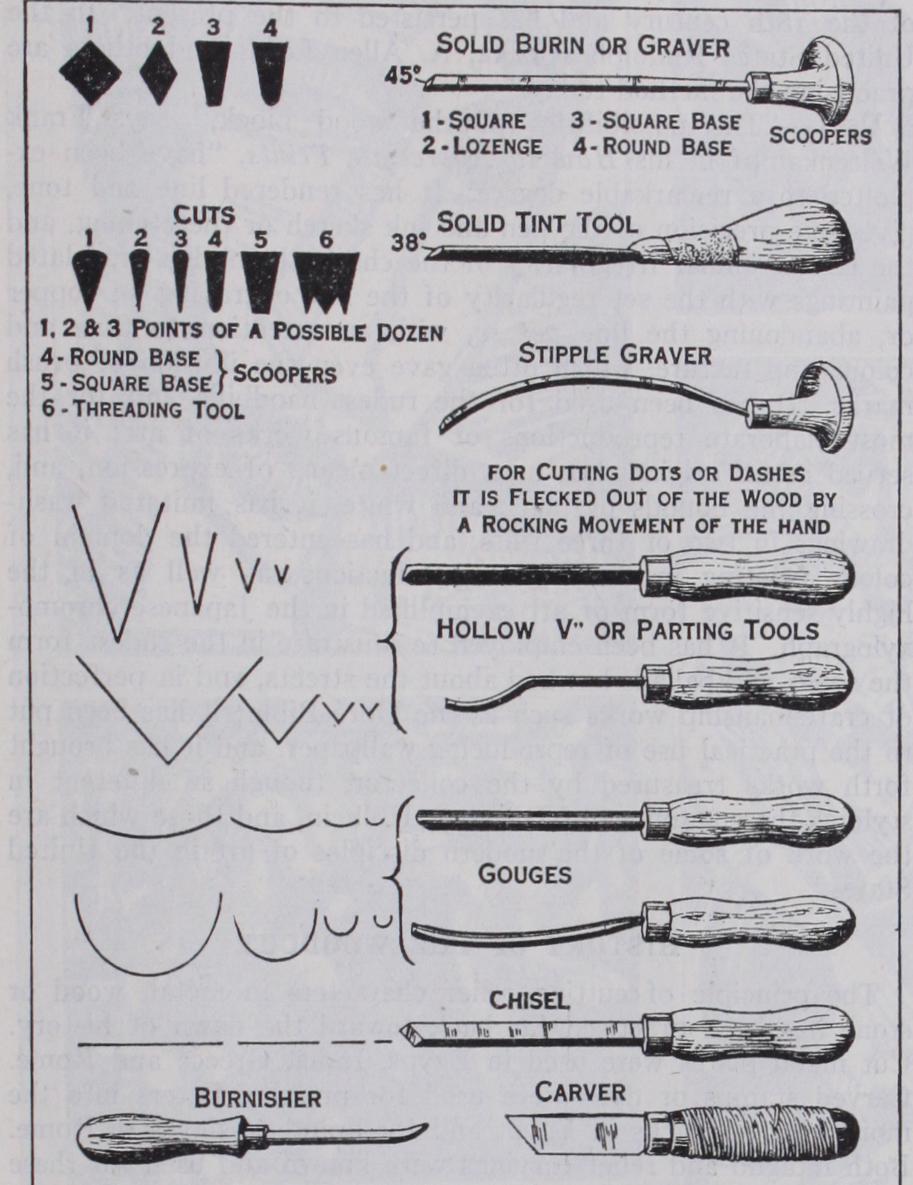

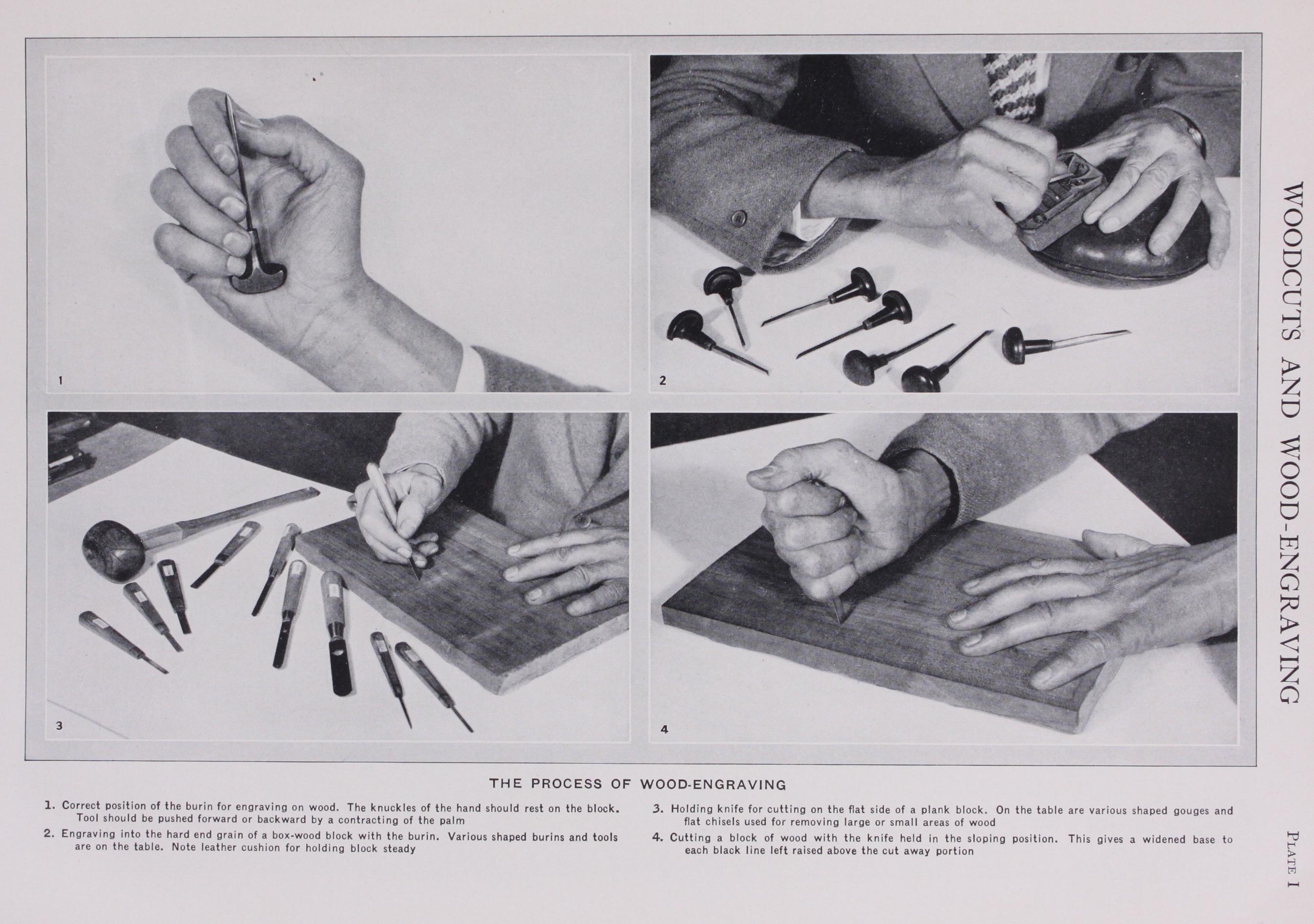

The black line cut is ordinarily made on a plank or block of soft wood like beech, apple, pear, cherry, sycamore or whitewood cut parallel to the grain as in ordinary lumber. Preferably it is of type height (about s in. as shown in fig. 2), planed and sanded to a perfectly smooth and level surface, and cut with a sharp knife. An ordinary pen knife will serve as a makeshift, but the carver (fig. 1) set in a cord-wrapped handle is better. The knife makes a sloping cut which tapers upward along each side of each line, thus supporting the line on a widened base (as shown in fig. 2).

When two lines are close together and parallel the sloping cuts on adjacent sides of each would remove a V-section between them. This V-cut can be made with one stroke instead of two by using the "V" or parting tool shown in fig. 1. Larger areas are