Wool

sheep, wools, developed, lincoln and till

In the time of William the Conqueror Flemish weavers settled under the protection of the queen at Carlisle, but later they were removed to Pembrokeshire. At various subsequent pe riods there were further immigrations of skilled Flemish weavers, who were planted at different places throughout the country. The cloth fair in the churchyard of the priory of St. Bartholomew was instituted by Henry II. ; gilds of weavers were established; and the exclusive privilege of exporting woollen cloth was granted to the city of London. Edward III. made special efforts to en courage wool industries. He brought weavers, dyers and fullers from Flanders; he himself wore British cloth; but to stimulate native industry he prohibited, under pain of life and limb, the ex portation of English wool. Previous to this time English wool had been in large demand on the continent, where it had a reputation exceeded only by the wool of Spain. The customs duties levied on the export of wool were an important source of the royal revenue. Edward III.'s prohibitory law was, however, found to be unworkable, and the utmost that both he and his successors were able to effect was to hamper the export trade by vexatious restrictions and to encourage much smuggling of wool. Thus while Edward III. limited the right of exporting to merchant strangers, Edward IV. decreed that no alien should export wool and that denizens should export it only to Calais. Legislation of this kind prevailed till the reign of Elizabeth, when the free exportation of English wool was permitted ; and Smith, in his Memoirs of Wool, points out that it was during this reign that the manufacture made the most rapid progress. In 166o the absolute prohibition of the export of wool was again decreed, and it was not till 1825 that this law was finally repealed. The results of the prohibitory law were exceedingly detrimental; the production of wool far exceeded the consumption; the price of the raw material fell; wool-"running" or smuggling became an organized traffic ; and the whole industry became disorganized. Extraordinary expedients were resorted to for stimulating the demand for woollen manufactures, among which was an act passed in the reign of Charles II. decreeing that all dead bodies should be buried in woollen shrouds—an enactment which remained in the Statute Book, if not in force, for a period of 120 years. On the opening up of the colonies, every effort was made to encourage the use of English cloth, and the manufacture was discouraged and even prohibited in Ireland.

Wool was "the flower and strength and revenue and blood of England," and till the development of the cotton trade, towards the end of the i8th century, the wool industries were, beyond comparison, the most important sources of wealth in the country. Towards the close of the 17th century the wool produced in Eng land was estimated to be worth £2,000,000 yearly, furnishing .18,000,000 worth of manufactured goods, of which there was ex ported about £2,000,000 in value. In 1700 the official value of woollen goods exported was about £3,000,000, and in the third quarter of the century the exports had increased in value by about £500,000 only. In 1774 Dr. Campbell (Political Survey of Great Britain) estimated the number of sheep in England at io,000,000 or 12,000,000, the value of the wool produced yearly at £3,000,000 (or about 5s. per lb.), the manufactured products at L12,000,000, and the exports at £3,000,000 to £4,000,000. He also reckoned that the industry then gave employment to 1,000,000 persons. In 1800 the native crop of wool was estimated to amount to 96,000,000 lb; and, import duty not being imposed till 1802, the quantity brought from abroad was 8,600,000 lb., 6,000,000 lb. of

which came from Spain. In 1825 the importation of colonial wool became free, the duty leviable having been for several previous years as high as 6d. per lb, and in 1844 the duty was finally re mitted on foreign wool also.

British Wools.

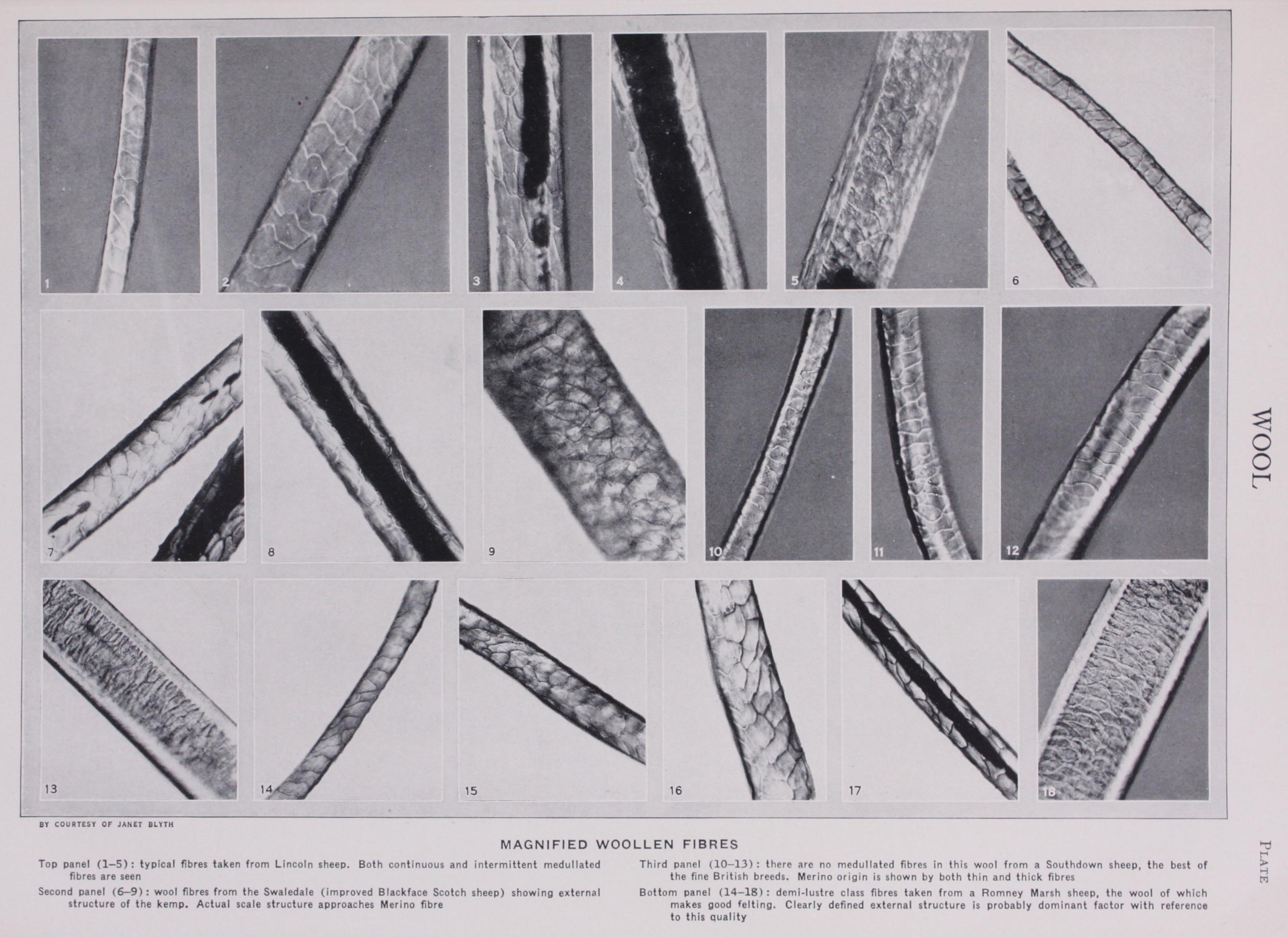

English wool, known the world over as being of a long and lustrous type was doubtless the kind so much in demand in the middle ages. That it was as long and lus trous as the typical Leicester or Lincoln of to-day is doubtful, as the new Leicester breed of sheep was only fully developed by Bakewell after the year 1747, and the latter day Lincoln is even a later development of a similar kind. As already remarked, the long and lustrous wools are the typical English, being grown in Lincolnshire, Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire, Devonshire, etc., in fact in all those districts where the pasturage is rich and specially fitted for carrying a heavy sheep. It is claimed that the lustre upon the wool is a direct result of the environment, and that to take a Lincoln sheep into Norfolk means the loss of the lustre. Attempts were made in the 18th century to develop a fine wool breed in England, George IV. importing a number of merino sheep from Spain. The discovery was soon made that it was difficult to main tain a breed of pure merinos in Great Britain, but the final out come was by no means unsatisfactory. By crossing with the in digenous sheep a race of fairly fine woolled sheep was developed. of which the present day representative is the Southdown—a sheep which feeds naturally on the downs of Sussex, etc., forming a marked contrast to the artificially turnip-fed Lincoln, Leicester, etc., sheep. Following the short, crimpy Southdown, but rather longer, come the Hampshire and Oxford down sheep; these are followed by Suffolk, Shropshire, Kent and Romney Marsh (Demi lustre), until at last the chain from the Southdown to the Lincoln (lustre) is completed. Of course there are several British wools not included in this chain. Scotch or black-face wool is long and rough, but well adapted for being spun into carpet yarns. Welsh wool has the peculiarity of early attaining its limit of shrinkage when washed, and hence is specially chosen for flannels. Shetland wool is of a soft nature specially suited for knitting yarns, while Cheviot wool—said to be a cross between merino sheep saved from the wreck of the Great Armada and the native Cheviot sheep—has made the reputation of the Scottish manufacturers for tweeds. North wool—wool from an animal of the Border Lei cester and Cheviot breed—Wensleydale, Masham and Ripon wools are also specially noted as lustre wools.