Bulgaria

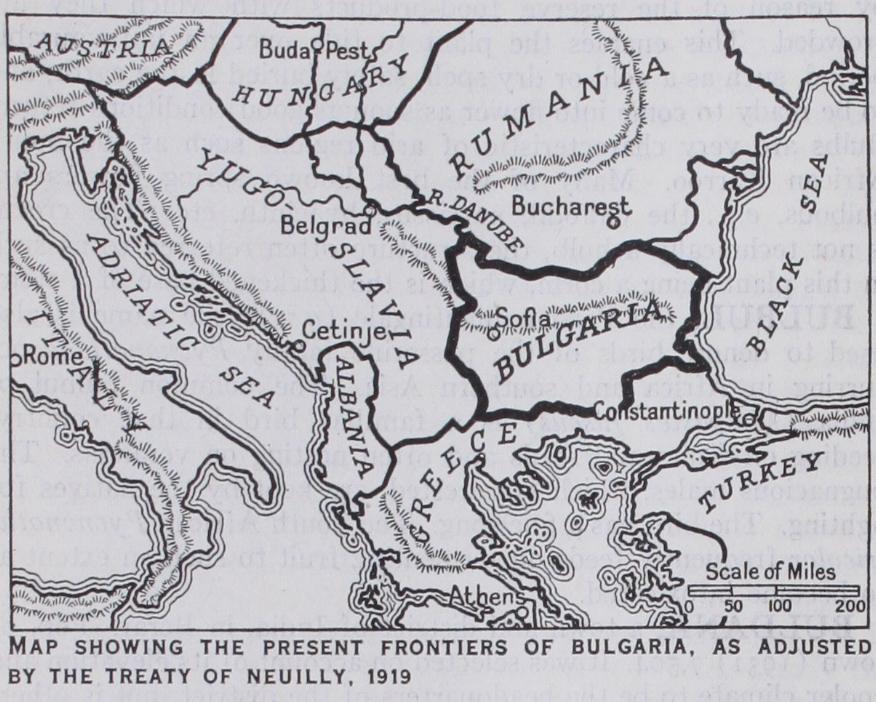

BULGARIA, a Balkan kingdom of roughly rectangular shape, lying to the east of the peninsula, with a total area of about 40,00osq.m. and a population of 6 millions. The south and west frontiers run through hilly country, separating it from European Turkey and Greece on the one hand and Yugoslavia on the other. With Rumania, the frontier is mainly the line of the Danube, while there is an eastern frontage on the Black sea. The trans verse Balkan mountains divide the main agricultural area of Bul garia into two parts, the northern tableland sloping gently down to the Danube and the basins and valleys of the Upper Maritsa system to the south. The latter are cut off physically from the open waters of the Aegean by the Rhodope upland, along or near the crest of which the frontier runs, and politically by Greece, which extends to the lower Maritsa valley. The Maritsa plains have, however, an outlet to the Black sea through the port of Bur gas. The Danubian tableland has in Ruschuk a port on the river Danube, and in Varna a more important outlet to the Black sea.

The existing frontiers date in part from the treaty of Berlin in 1878, and in part from later ones, including that of Neuilly (1919). Bulgaria is thus essentially a modern state, having little relation, whether territorially or socially, to the Bulgar empire of the 9th and loth centuries. The population density of per square mile, considerably above the average for the penin sula, may be associated with the relatively high percentage of arable land, 41% of the total surface being under cultivation, while forests cover nearly 30% of the remainder. Within the peninsula Bulgar, or Bougar, means cultivator, or ploughing peas ant, with an implication of servitude as compared with the free peasants of Serbia. With this is connected the fact that both in the loess-covered Danubian tableland to the north and in the alluvial basins of the Maritsa to the south of the Balkan moun tains there are fairly extensive level and fertile areas, well fitted for cereal cultivation, wheat being particularly important in the northern area.

The second fundamental fact is that the Balkan chain, owing both to the presence of passes and to the slope of the northern tableland, is not, as might be supposed, a barrier between the two agricultural areas. Two great highways may, indeed, be said to converge in the land which has become Bulgaria. One is the route which comes from Central Asia by way of the steppes and grasslands of southern Russia, and can be continued to the south over the Balkan passes. The other is that which links Asia Minor to Europe by the straits, and can be continued along the Maritsa valley, and so to the Morava and the Danube at Bel grade The two unite in the plains of southern Bulgaria.

In consequence of these two facts—fertile lands able to form a granary for a great power and converging routes—two strands may be said to be interwoven in the history of Bulgaria. So far as the mass of the people is concerned, 8o% of whom are peasant cultivators, the ruling passion has been to obtain and then to keep their plots as freeholds. But at successive periods, whenever the power enthroned at Constantinople seemed to be weakening, their leaders have dreamed of making themselves heirs of Byzantium. In the 9th century Simeon, the Bulgar chief, after an unsuccess ful attempt to take Constantinople, proclaimed himself Tsar (_ Caesar). In 1908, at the time of the Young Turk revolution, Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria adopted the same title, still held by the reigning king. The participation of Bulgaria in the World War on the same side as Turkey and against her former pro tector, Russia, may seem at first sign an anomaly. But it has to be remembered that Greece had also Byzantine ambitions, and that Serbia desired to expand along the other great highway which leads to Salonika. Further, with the development of Bulgaria's export trade in cereals, particularly wheat, the question of easy access to the Aegean has become of great importance. The actual result of Bulgaria's participation in the War was the loss of ter ritory, particularly of the small strip on the Aegean coast, ob tained at the peace of Bucharest, with the port of Dedeagach.

Essentially, then, post-war Bulgaria is a land of peasant culti vators, producing a surplus of cereals and other agricultural com modities, but deprived of direct access to its western markets by the need of exporting these by the Black sea, with a subsequent passage of the straits.

From what has been already said it is clear that the country falls into four regions :—the northern or Danubian tableland; the mountain belt of the Balkans; the valleys and basins of the Maritsa system; the part of the Rhodope upland falling within the country, with its north-western continuation, which converges towards the Balkan chain, and a western hill belt separated by the Struma valley.

Danubian Tableland.

This, often called the Balkan Fore land, is the area between the low northern scarp of the folded Bal kans and the Danube. The Balkans consist largely of schists and granite, with some limestones, while the tableland is floored by un disturbed, horizontally-bedded rocks, mainly cretaceous lime stones, often concealed by a deep mantle of loess. The Danube, which forms the northern frontier to a point downstream from Ruschuk, varies in width from 1/5 of a mile to well over a mile and, despite its navigable waterway, forms an excellent boundary. Its Bulgarian bank is high, loess cliffs 5-600ft. in height rising above the valley floor, while the opposite or Rumanian bank is low. The river is liable to flooding in spring and early summer, as the snows of the plains and higher grounds melt successively, and its valley is swampy, with lagoons rich in fish, especially carp and sturgeon, reed beds and willow brakes. It is malarious in summer and bitterly cold in winter, when navigation is im peded by ice, and the river may freeze over. No bridge crosses the river in Bulgarian territory.Downstream from Ruschuk the frontier leaves the river to pass in a south-easterly direction to the Black sea, which is reached near the port of Varna. This means that the whole of the Dobruja lies within Rumania. Till 1913 its southern portion was included in Bulgaria, and the present frontier has been drawn quite defi nitely on strategic grounds. It runs through a gentle swelling of the surface, formerly heavily wooded, to which it owes its Turk ish name of Deli Orman, or wild forest. The trees have been largely cut down but patches of stunted oaks remain on the high er levels, where also the limestones appear on the surface, giving rise to a karstic type of country. This wooded belt forms the frontier and dominates alike the steppe areas of the Rumanian Dobruja to the north and the not very dissimilar steppe-like country of eastern Bulgaria to the south.

The tableland, as thus defined, forms a well-marked unit. The underlying tabular rocks display south-to-north faultlines, and the rivers which run north to the Danube follow these. To the west the Isker, the second largest river in Bulgaria, the Maritsa taking first place, breaks through the whole Balkan chain, thus bringing the high basin of Sofia (i,800ft.) into communication with the Danubian tableland. The valley is traversed by a rail way, and the choice of Sofia as a capital is thus justified by the fact that it is linked to both the great productive areas, to the Maritsa plains by the main Belgrade-Constantinople route and its Bulgarian branches, and to the tableland by the Isker valley. Both west and east of the Isker smaller streams rising in the Bal kans flow direct to the Danube, the Yantra, to the east, being the largest and most important of these. All carry a comparatively small amount of water, and some even dry up in summer ; but owing to the soft loess deposits all have cut out remarkably deep valleys. It is a general rule that the right bank of each stream is higher than the left, where plains of deposition occur.

These deeply-sunk rivers, with their fairly extensive valley plains, are of very great importance from the human standpoint. The plateau levels above, dry because of the limestones which underlie the porous loess, exposed to cruelly cold winds in winter and to desiccating blasts in summer, practically devoid of wood, so that dried dung has to be used as fuel, are remarkably produc tive, especially in favourable seasons, but do not attract settle ment. The valleys have a better climate, owing to shelter from strong winds ; spring water is available as compared with the dry plateau above; a greater variety of crops can be produced. They serve, therefore, as natural sites for towns and villages, and Trnovo, in the Yantra valley, should be noted as typical. Once a Bulgarian capital, it owes its greater size and importance as corn pared with its analogues to its river. This affords a line of access to the Shipka pass (4,363ft.), while one of its tributaries allows the passage of a railway to the Maritsa plains. A certain amount of market-gardening is carried on around the town, and it is characteristic generally of the valleys that, as compared with the almost uniform sweep of the wheat fields above, maize, the bread plant, is grown, and with it plants like tomatoes and peppers, so important where tasteless maize forms a large part of the diet, as well as sueh crops as lucerne and sugar-beet. In the more sheltered and lower parts of the valleys the vine can also be grown. These valley settlements, where a measure of protection is obtained both from the rigours of nature and the risk of in vasion by man, are a striking feature, and they involve long daily journeys from the home to the fields above.

To the east the Provadi and Kamchik rivers find their way di rect to the Black sea instead of to the Danube, Varna being situ ated near the mouth of the former. In this eastern area the steppe-like character becomes accentuated, and the upper levels may be more suited for summer pastures than for wheat culti vation.

This whole tableland region has undergone great changes since the time of the treaty of Berlin. Before that date it was the seat of great feudal domains, the Turkish tchiflik, its physical features fitting it for this form of exploitation. Since that time it has been divided up into small holdings, worked by the peasants, the typi cal Bulgarians. Their industry, their frugality, their remark ably high level of agricultural skill, their passion for education, have been remarked by all observers. It is inevitable that in view of the conditions and of their history they should show also the defects of their qualities—a thriftiness verging on greed of gain, a "dourness" which is in marked contrast to the light-heart edness of the Serbs. Much of the wheat grown is exported from Varna, and thus forms a money crop, the peasants living chiefly on the cheaper maize. There are no minerals, and the towns, placed mainly either on the Danube or within the tributary val leys, are primarily market centres, with minor industries, usually dependent on the working up of local raw material, such as mill ing, wine-making, the making of caviare in the Danubian fishing towns, woollen and leather goods. The gold and silver filigree work of Vidin and Ruschuk is interesting, because artisans practising traditional crafts linger in various parts of the peninsula and re call the fact that its early Byzantine civilization did not disap pear completely during the long Turkish night when the Ottoman ruled the Balkan peninsula.

Mountain Belt of the Balkans.—The Balkan belt is very different from the tableland, both as regards physical features and the human response. From the valley of the Timok, the lower course of which forms the frontier with Yugoslavia, the folded chains extend over a distance of some 375 miles, first in a south-easterly and then in an easterly direction to the Black sea, where they break off abruptly. The gorge of the Isker to the west and the Demir Kapu pass to the east divide them into three sections, of which the central is at once highest, rising to a maximum of nearly 7,800f t., and narrowest, being only some 18m. wide. The western section has a maximum height of a little over 5,000f t., while the eastern is lower and divided into two or three separate ridges.

A striking feature of the chain is the appearance on the south of the "shadow" range of the Anti-Balkans, divided into the Sredna Gora to the west and a narrowed eastern portion called the Karaja Dagh. This range is separated from the Balkans proper by the sub-Balkan depression, a very fertile valley area. Its western part is drained by the Striema tributary of the Marit sa, which has cut back between the Sredna Gora and the Karaja Dagh and separates the two, and the eastern and larger part by the Tun j a, a powerful left-bank tributary of the Maritsa with numerous feeders.

Despite the presence of schists and granites, of which they are largely composed, and the heights to which they rise, the Bal kans present generally the appearance of an upland rather than of a mountain chain. Their summits are rounded, forming un dulating summer pastures, rocky peaks being absent, and the slopes are heavily wooded, chiefly with oak and beech. To the south, especially in the Central Balkans where there is much faulting, the hill country is separated by high and steep scarps from the fertile sub-Balkan depression ; the northern scarp is much lower and less conspicuous. Though as a whole scantily peopled the Balkan region contains a certain number of basins suitable for settlement, of which those of Kotel and Gabrovo may be specially mentioned. Coal, not of very good quality, and not in large amount, occurs on the northern side near Gabrovo and on the southern near Slivno, and there are also oil-springs and some small deposits of copper, lead, and zinc.

It is clear from this description that the Balkan region, despite its elevation and the absence of the wide tracts of fertile soil found in the tableland, has certain advantages of its own. There is a greater variety of products and of possible occupations, for in addition to agriculture, based mainly on the hardier cereals, rye and barley, with buckwheat, the forests give occupation to wood-cutters and charcoal-burners, and the pastures permit of a considerable development of the pastoral industry. Since in ad dition to the coal beds there is a certain amount of water-power, minor manufactures can be carried on, and the mineral deposits, if insignificant in themselves, are sufficient to support small local industries. Further, in the days before railways, the traffic across the passes afforded an accessory source of wealth and increased the market for local products, particularly saddlery, blacksmith's work, and so forth. Other industries carried on are the making of woollen goods, pottery, cutlery, wooden articles, copper goods, and so on. Apart from these resources the region has gained in the past from the fact that the physical features give some oppor tunity of evading the control of feudal lords, while at the same time the scarcity of arable land makes such control less profitable and thus not likely to be exerted to the same extent as in more productive areas. In point of fact it is found that some trace of national feeling seems to have persisted even through the days when the Turkish yoke bore heaviest, and certain of the mountain towns and villages served as foci for the Bul garian nationalist movement. The first Bulgarian schools and libraries were founded in Kotel and Gabrovo, and some of the leaders came from the Sredna Gora region.

Valleys and Basins of the Maritsa System.

The Maritsa region, taken in the larger sense to include the sub-Balkan de pression, differs profoundly from the two regions already de scribed. Forming the heart of the Eastern Rumelia of the treaty of Berlin, it displays in its climate Mediterranean influences, while in its crops, including roses for attar, rice, cotton, tobacco, vines, peaches, walnuts, mulberry for silkworm-rearing, with wheat, the effects of the position and of the shelter given by the hills to the north are clearly seen. Towns of ancient origin, such as Philippopolis (Plovdiv), indicate its historical importance as a highway, and the traces of the earlier Turkish occupation its value to the owners of Constantinople. Till the treaty of Berlin and later the population was of a very mixed nature, with Turks, Greeks, and Slays, in addition to Bulgatians. Since that time the Bulgarian element has increased greatly, but the gardener cultivators here differ in some respects from the peasants of the tableland.Of its two sections the sub-Balkan depression is of great in terest from the standpoint of physical geography. There is rea son to believe that it was once occupied by a continuous river, flowing from west to east and entering the Black sea near the present port of Burgas. It is believed that sections of this hypo thetical river were tapped, or captured, successively by feeders of the Maritsa, cutting back into the sub-Balkan range. The re sult has been to give rise to a series of basins, arranged in a line from west to east, and separated from each other by comparative ly low sills. The more westerly of the basins are drained by streams, the Topolnitsa and the Striema, which flow directly to the Maritsa, but the eastern members of the series are strung along the Tunja, a powerful river with a number of tributaries. Where the slopes of the Karaja Dagh sink down eastwards to the plain, the Tunja swings round at a sharp angle, running south ward to join the Maritsa, beyond the confines of Bulgaria, at the town of Adrianople. The result of this arrangement and of the fact that the Anti-Balkan range is highest in the west, in the Sredna Gora, is that the western basins are smaller, higher, and more definitely cut off by gorges from the main Maritsa valley than the eastern ones. The most easterly, that of Slivno, prac tically merges into the Maritsa basin, for to the south of it the Karaja Dagh is represented only by hilly country.

Among the other basins mention may be made of that of Zlatitsa, the most westerly, containing the town of that name. It is small and noted especially for its fruit-trees, including walnuts. The next basin, that of Karlovo, is watered by the feeders of the Striema, and vines and roses grow freely. But the most important and largest of the basins is that of Kazanlik, in the Tunja sec tion, which has always been celebrated for its beauty and fertility. Here are the most extensive rose gardens in the world, essences being distilled particularly at Stara Zagora; under modern con ditions more prosaic crops, such as sugar beet and potatoes, are, however, largely displacing the rose bushes, even though attar is still an important export.

The Maritsa river rises in the Rhodope and after leaving the hills enters a great basin, the largest of the areas of depression which are characteristic of the peninsula. It lies between the Anti Balkan range to the north and the Rhodope upland to the south and west and thus the river has two sets of tributaries. Those coming from the wooded Rhodope have a fairly even flow, and some of them are used for transporting the timber to the lower grounds. The left-bank tributaries are steep and, flowing as they do mainly over bare slopes, show great fluctuations in volume, and when in flood carry large amounts of silt. The main stream, which has low banks, is constantly changing its course and its valley is marshy. Rice is cultivated on irrigated land, particularly round the junctions of the northerly streams. Maize, wheat, and tobacco are grown somewhat farther from the river, while the slopes are planted with vines, mulberries, and various fruit-trees. Some cotton is grown, the fact being interesting even if the amount is not large. In addition to Philippopolis, Tatar Bazarjik is an important town, and there are many others.

Farther east, towards the north-to-south section of the Tunja and beyond the river, the climate becomes drier and the country more steppe-like. In this district wheat is the main crop, accompanied by stock-rearing, and the wheat-producing area extends to the hinterland of the port of Burgas. Farther south are the slopes of the Istranja hills, which extend to the shores of the Black sea. These are mostly wooded; but the scrub-like character of the woods, made up of low, twisted and gnarled oaks, indicates the effects of the climatic conditions. This region forms a general exception to the rule that the sub-Balkan depression and the Maritsa basin are areas of great fertility. They owe this fer tility to the alluvial deposits by which they are floored, the loess of the tableland not reappearing south of the Balkans.

The Rhodope Upland.

If the Maritsa region repeats, with differences, the characteristics of the tableland, so too the Rhodope upland and its continuations repeat, again with marked contrasts, some of the features of the Balkan chain. Sofia—tucked away in its little upland basin but with arm-like highways stretching out to the eastern productive areas as well as to the west--of ancient origin but modern aspect, is peculiarly representative of Bulgaria. That much of its trade is in the hands of Jews is but one illustration of the difficulty of modernizing rapidly a state mainly peopled by peasants. Another is the intense pre-occupation of the townsfolk with politics of the "realistic" type. A some what careful study of the exact relations of the Sofia basin to the mountain massifs and basins of the upland in which it lies is essential in order to grasp the reason why the political history of Bulgaria has been so troubled, and particularly why the Macedo nian question has played and is playing so important a part.

Western Hill Belt.

So far the name Rhodope has been used in a broad and general sense for the hill country in the south-west of Bulgaria, of which strictly speaking it forms but a part. From the western Balkans, or Stara Planina, there extends south a region of broken country along which the frontier be tween Bulgaria and Yugoslavia runs. The southern part of this receives the name of Osogovska Planina, and has a certain indi viduality of its own, due both to its height and to the fact that the Struma river makes a definite line of separation between it and the still higher mountains to the east. The Struma, which has a general north-to-south direction, rises in the Vitosha Planina, south-west of Sofia, a mountain mass rising to heights of over 6,500 feet. After leaving Bulgarian territory it flows through Greek Macedonia to the Aegean. To the east of the valley line is a long belt of mountain country extending from the Vitosha Planina to the Rila mountains, a beautifully wooded group with a maximum height of nearly 9,600ft., and continued into the Pirin Dagh to the south and into the Rhodope Planina to the south-east. The Isker river, which passes through the basin of Sofia, rises in the Rila mountains and thus to the south of the source of the Struma, their headwaters overlapping, as it were. The Vitosha mountains form a certain obstacle to routes from Sofia into the Struma valley, but can be turned both to the north west and to the south-east.The Struma, running as it does between the complex hill country which bounds the Morava-Vardar furrow on the east and the high and alpine mountains of south-western Bulgaria, is of great importance, and that for two reasons. In the first place the main stream and some of its tributaries pass through basins of considerable fertility, which gain in importance from the sur rounding mountain land. Secondly, their valleys open out routes to the heart of the peninsula as well as to the Aegean, these routes acquiring special significance from the fact that they can be reached from Sofia.

Some of the basins may be noted. The highest is that of Pernik (about 2,5ooft.) where good brown coal (lignite) occurs. At a much lower level is that of Kustendil (about 1,60o feet). This is very fertile, producing vines, tobacco, and plum trees and hav ing a bathing establishment, due to the presence of hot sulphur springs. From the plain, over the slopes of the Osogovska moun tains, there passes an important route to Uskub in Yugoslavia. Of the basins watered by tributaries that of Dupnitsa, traversed by a left-bank tributary and lying in nearly the same latitude as Kustendil, is important. This also is fertile and has direct access to Sofia. Farther down the Strumitsa, a right-bank tributary, flowing west to east, has a very fertile valley of which only a part, according to the 1g19 treaty, falls in Bulgaria. This valley was the scene of severe fighting during the World War, and affords a good line of access into the region of the lower Vardar valley. Before 1919 the Bulgarian frontier lay farther to the west, and the chopping of the fertile valley into two parts, if it has a stra tegic justification, does necessarily increase Bulgarian interest in Macedonia.

The Rhodope and Rila massifs, built as they are of hard rocks, are much more formidable mountains than the Balkan chain. The peaks are bare and rocky with old glacial cirques and moraines dating from the glacial period, and the valleys are deeply cut and steep. Woods are abundant, with beech and oak below and pine and fir above, and there are extensive summer pastures at the higher levels. Though the more elevated areas are unfit for perma nent habitation, the margins and the included valleys offer oppor tunities and are sufficiently diverse to permit of the development of separate human strains. Thus the Rhodope region is the home of the Pomaks or Muslim Bulgarians, who adopted the religion of the Turkish conquerors and became instruments in the oppres sion of the Christians. They are, or were, mainly wood-cutters and charcoal-burners, while the Vlachs found in the region in summer are, as usual, herdsmen. Another point of interest is that while the monastic life does not as a rule make much ap peal to the Bulgarians, the dense woods of the higher moun tains here, as in so many parts of Europe, lodge monastic estab lishments to which great forest tracts were formerly attached. The most interesting of these is the famous Rila monastery, placed at a height of nearly 3,9oof t. in the massif of the same name, and a favourite place of pilgrimage. It is of ancient origin, though the existing buildings are modern.

Neglecting the deep gap of the Struma valley and looking at this upland country as a whole, it is obvious that, even more than the easily crossed Balkans, it is fitted to serve as a refuge for fugitives, and thus as a centre for the growth of a spirit of revolt. Bulgaria, as has been seen, arose as a unified state in the period 1878-1908 by the combination of the two productive areas linked by the Balkan passes. But to the west of the great upland lie the basins and hills of Macedonia, where the cultivating peas ants were also oppressed by the Turkish conquerors. The Struma and its feeders link Sofia to Macedonia by various routes, not difficult as difficulty is counted in the peninsula. Apart altogether from the much disputed question of the "racial" affinities of the Macedonians, the position of Sofia made it inevitable that Bul garian politicians should interest themselves in the Macedonian problem, both with a view to the enlarging of the state bounda ries and in the hope of connecting the state capital directly with the Aegean. The great complexity of the structure of the penin sula, and particularly the fact that the rivers tend to flow through sunken basins, capable of settlement, but separated rather than linked by gorges difficult of passage, has made the drawing of frontiers satisfactory both from the strategic and economic stand point an almost insoluble problem. It is this geographical fact rather than the real or supposed racial differences between Serbs and Bulgarians that is the basis of many of the troubles of the peninsula.

Population and Government.—According to the census of three-quarters of the population is Bulgarian, and about half of the remainder Turkish. Elementary education is free and ob ligatory, and in of the male population and 57.2% of the female population were literate. Of the population 8o% be longs to the Bulgarian (Orthodox) Church, 14% is Moslem, .8% Jewish and Roman Catholic. The legislative authority is the So branye, which is composed of 16o members, but since 1937 party candidature has been prohibited, and government tends to be authoritarian in character.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-A large number of books on Bulgaria has recently Bibliography.-A large number of books on Bulgaria has recently been published in Germany. See also Logio, Bulgaria (Manchester, 1937) ; Prost, La Bulgarie de 1912 a 193o (Paris, 1932) ; The Balkan States (Information Dept. of the Royal Inst. of International Affairs, (M. I. N.) Historical.—From the earliest times (A.D. 678) when the Bul garians, a Slavonian tribe, first established a kingdom, the country has at intervals been the scene of turbulence and bloodshed. After suppression by the Emperor Basil in 1014, the kingdom was re established in 1186, but only to be again suppressed and annexed to Turkey in 1396. In modern times a revolution against Turkish rule in 1876 was ruthlessly suppressed. From the date of the war against Serbia in 1885-86, Bulgaria was the scene of constant revolutions and of participation in wars against Balkan neighbours until, in 1915, the Bulgarians seized the opportunity to strike a deadly blow from the rear against the army of her old enemy, Serbia, then engaged against an army of the Central Powers. The Bulgarian army thenceforward held its own against an Allied army operating from Salonika until the tide had turned definitely in favour of the Allies, when Bulgaria was the first to sue for an armistice (Sept. 29, 1918) which was followed by a peace treaty in which the Allied triumph was embodied. Bulgaria still had an intact army of about 400,000 (ration strength) with reserves of about 112,000 at the close of the World War.

Present-day Army.—Since the conclusion of the Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine (Nov. 27, 1919) present-day Bulgaria has pos sessed land frontiers of 1,765km. and 267km. of coast on the Black sea, as shown below. Universal compulsory military service was abolished by that treaty, and only voluntary enlistment was allowed. The total number of military forces was limited to 20,00o, including officers and depot troops. The maximum strength of an infantry division (the largest formation allowed) was limited to 414 officers and 10,780 other ranks, of a cavalry division to 259 officers and 5,38o other ranks, of a mixed brigade to 198 officers and 5,35o other ranks. The minimum strength of these and of all smaller units, whether comprised therein or not, was also prescribed. A maximum number of three guns, of two medium or light trench mortars and 15 machine guns or auto matic rifles per 1,000 men was laid down. No piece of over 105 mm. calibre was permitted except in the armaments of fortified places. The number of gendarmes and similar organizations armed with rifles was limited to io,000, and of frontier guards to 3,000. The grand total of rifles in Bulgaria is thus 33,000. Officers must serve for at least 20 years with the active army, not more than 5% retiring annually ; other ranks for 12 consecutive years.

Recruiting and Service.—In accordance with the above, re cruiting in the Bulgarian army is voluntary, with enlistment for 12 years which may be extended up to the 4oth year of age. En listment may be at any age between 18 and 28. Enlistment in the gendarmerie and frontier force is for 12 years, with possible ex tensions up to the age of 5o years. The budget effective strength of the army in 1927-28 was 19,97o, including 999 officers, and of the gendarmerie and frontier guard 9,798. Additional officials and employees numbered 2,527. The usual arms and auxiliaries are included. The infantry is organized in six regiments of three battalions, the cavalry in three regiments of four squadrons, the artillery in eight groups, of which five are equipped with field guns ; there are five battalions of engineers, two railway bat talions and one communication section.

Higher Command.—The Ministry of National Defence is the supreme military authority. The Ministry includes inspectors of the various arms, besides departments for dealing with finance, military law, topography, education and auxiliary services. The army staff deals with organization, recruiting, military training, supplies, Bulgarian defence and education of officers. The War Council, an advisory body embodied in the Ministry, is con vened, when necessary, under the authority of the minister of war.

Distribution.—The frontier guard, a special body of dis mounted men, is organized in eight sectors, each being responsi ble for three frontier posts. The frontiers with Turkey measure 208km., with Greece 459km., with Jugoslavia 498km., and with Rumania 600km., making a total land frontier of 1,765km. The sea coast measures 267km. The army units are distributed fairly evenly amongst the centres of population.

Military Education.—In accordance with the Treaty of Neuilly, there is only one military school for cadets. They pro vide the officer class from the age of 20 and upwards, up to the age of 45 for captains, 5o for majors and lieutenant-colonels, S5 for colonels and 6o for generals. There are also special courses for private soldiers to qualify for promotion to non-commissioned rank, and also for non-commissioned officers. The military acad emy is directly under the Ministry of War.

Special Armament and Permanent Fortresses.—Every battalion of infantry contains a machine-gun company, a bombing company and three rifle companies. A cavalry squadron contains a machine-gun section. Engineer battalions and communication sections each contain a machine-gun group, and railway battalions each a machine-gun section. No special training doctrine has been disclosed. The Treaty of Neuilly forbids the construction of new fortifications or fortified places in Bulgaria, and the armament of such places, as existing in Nov. 1919, may not be strengthened. Ammunition supply must be limited to Soo rounds for each piece of I o• 5 cm. calibre or above, and to 1,500 rounds for that and for lower calibres. Army air services are forbidden by the Treaty of Neuilly. Estimates for civil aviation appear in the civil budgets.

See also Treaty of Peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Bulgaria, and Protocol. Treaty Series 1920, No. 5 ; League of Nations Armaments Yearbook, 1928. (G. G. A.)