Burma

BURMA, though formerly a province of the Indian empire, is geographically a part of Indo-China, and is frequently called by the French "Indo-Chine anglaise." The province of Burma, as constituted since the annexation of Upper Burma in 1886, comprises the British territory of Upper and Lower Burma, the extensive native States known as the Federated Shan States, and Karenni, as well as several tracts of unadministered territory in the more remote parts. Lower Burma corresponds to the area acquired by the British Indian Government in the two wars of 1826 and 1852, while Upper Burma is the former independent kingdom of Burma, annexed on Jan. 1, 1886. The province stretches from 9° 55' to about 28° 3o' N. and from long. 92° 1o' to Io I ° 9' E. The extreme length from north to south is almost 1,200m. and the broadest part, which is in about lat. 21° N., is 575m. from east to west. The total area is estimated at 262,732 sq. miles. Burma proper, inclusive of the Chin hills and the ad ministered Kachin hill tracts, occupies about 184,102 sq.m., the Shan States, which comprise the whole of the eastern portion of the province, some 62,305 sq.m., and the unadministered territory some 16,325 sq. miles. Thus the province of Burma is the largest of the provinces of India.

Roughly half of Burma lies outside the Tropics, but the con figuration of the country is such that the whole may be regarded as a tropical country. In the north the boundary between Burma, Tibet and China, has not yet been precisely determined. The north-western frontier touches Assam, the dependent State of Manipur, and those portions of Bengal included in the Lushai hills and Chittagong. On the west the boundary is formed by the Bay of Bengal, in the south-west by the Gulf of Martaban. On the east the frontier touches the Chinese province of Yunnan, the Chinese Shan and Lao States, French Indo-China and Siam. In the south the boundary is formed by the Pakchan river.

falls nat urally into three great geomorphological units : (a) The Arakan Yoma, a great series of fold ranges of Alpine age, which forms the barrier between Burma and India. The foothills of the Arakan Yoma stretch as far as the shores of the Bay of Bengal. (b) The Shan plateau massif, occupying the whole of the east of the country and ex tending southwards into Tenasserim. The massif forms part of what has been called the Indo-Malayan mountain system and has existed as a geomorphological unit since the close of the Mesozoic. (c) The Central basin, lying between the Arakan Yoma and the Shan plateau. Formerly a gulf of the early Tertiary sea, open to the south, it is now occupied by a great spread of Tertiary rocks.

The great mountain range of the Arakan Yoma and its continuation northwards has a core of old crystalline rocks. On either side are hard, folded sedimentary rocks, mainly Tertiary in age. Rocks of Jurassic and Cretaceous age are also known to occur, but the geology of the ranges is still very imperfectly known. Extensive strike faulting occurs along the eastern flanks of the Arakan Yoma and large serpentine intrusions, probably of Cretaceous age, are associated with the faults. Chromite and other useful minerals are known to occur, especially in association with the serpentine, but are not at present exploited. The western edge of the Shan plateau massif is well marked both physically and geologically. It rises abruptly from the valley, and for 400 or 5oom. the edge is formed by a long strip of granitic or gneissose rocks. The predominant rocks in the Shan plateau are gneisses—which yield the rubies and other gems for which Burma has so long been famous—and a massive limestone of Devono-carboniferous age. Rocks of all ages from pre-Cambrian to Jurassic occur in the massif, whilst de posits of late Tertiary and Pleistocene age occupy old lake-basins. In pre-Cambrian rocks at Mogok occur the principal ruby "mines," —but the industry is now of minor importance. At Bawdwin, associated with a group of ancient volcanic rocks, are very exten sive deposits of silver-lead ore, mainly argentiferous galena, which are worked by the Burma Corporation, Ltd., and smelted at the nearby works of Namtu. The refined silver and lead are sent by rail to Rangoon for export. Other silver-lead deposits are known in other parts of the Shan States, and have been worked in the past by the Chinese. Tenasserim forms a continuation of the tin bearing belt of Malaya, and large quantities of tin and tungsten are obtained. Geologically this portion of the Indo-Ma.layan moun tains consists of large granitic intrusions, elongated in the north south direction and intruded into a series of ancient rocks of un known age. The basin of the Irrawaddy between the Arakan Yoma and the Shan plateau, consists almost entirely of Tertiary rocks. The beds are remarkable for their enormous thickness ; the Eocene beds reach upwards of r 5,000f t. ; the Peguan (Oligo Miocene) upwards of i 6,000f t., and the Irrawaddian (Mid Pliocene) upwards of 5,000 feet. Forming a line down the centre of the basin are the well known oilfields of Burma. The oil occurs mainly in rocks of Peguan age. From north to south are the fields of Indaw, Yenangyat, Singu, Yenangyaung, Minbu and several minor fields. The most important fields are Yenangyaung and Singu. Brown coal also occurs in considerable quantities in the valley of the Chindwin and elsewhere in the Tertiary rocks, but as yet has been little used. Along a line running, roughly, along the centre of the ancient Tertiary trough, are numerous extinct volcanoes; some form small tuff cones with small crater lakes; others are plugs of rhyolitic matter, but the largest is the com plex cone of Mt. Popa.

Physical Features.

The three physical units into which Bur ma is naturally divided have already been mentioned as geo morphical units. Burma is separated from the remainder of the Indian empire by a long fold range, uplifted at the same time as the Himalayas in India. In the north the range is narrow, and known as the Patkai hills. Further south the direction changes from south-west to south and the ranges broaden out, enclosing the Manipur plateau. The individual parts have received differ ent names, and include the Naga hills, Chin hills and Lushai hills, but from Manipur southwards the whole range is known as the Arakan Yoma. As such it becomes narrower, curves round to south-south-east and terminates in Cape Negrais, though geo logically the same series of folds is continued in the Andaman and Nicobar islands. A small part of Burma—the division of Arakan (q.v.)—lies between the Arakan Yoma and the Bay of Bengal. Some of the peaks of the Arakan Yoma rise to over and the highest is believed to be Mt. Victoria. The whole range forms an effective barrier between Burma and India proper. The east of Burma, including the whole of the Shan States (q.v.), is occupied by a plateau, which forms part of the great Yunnan plateau of China. The plateau averages 3,000ft. in height, but its surface has been much dissected, and running through the centre from north to south is the deep trough occu pied by the Salween river. Southwards, the plateau passes through Karenni into that part of Burma known as Tenasserim, and gradu ally loses its plateau character.Between the Arakan Yoma on the west and the Shan plateau on the east, lie the basin of the Irrawaddy and its great tributary, the Chindwin, and the basin of the smaller Sittang. This is for the most part a lowland area, with ranges of hills—of which the Pegu Yoma is the most important—running from north to south. Almost in the centre the extinct volcano of Mt. Popa reaches nearly 5,000f t. above sea-level. The Arakan coast of Burma is Pacific in type, it is rocky and dangerous, backed by high moun tains and fringed by islands. Of the islands, Ramree and Cheduba are the largest. The Tenasserim coast is similar; in the south is the Mergui archipelago. Between the Arakan and Tenasserim coasts lies the low delta of the Irrawaddy and Sittang rivers.

Most of the hilly and mountainous regions were formerly forest covered, and over large areas have good, fertile forest soils. Where clearings have been made, temporary cultivation has de stroyed the virgin richness of the soil. In the wetter regions the heavy rains often entirely wash away the soil from cleared hill sides and expose the bare rock. The limestone rocks of the Shan plateau are usually covered by a thin red soil from which the lime has been entirely leached out. The richest soils in the province are the alluvial soils of the flat Irrawaddy delta and the broad river valleys. Excellent loamy soil is also afforded by the mixed clays and sands of the Peguan rocks, but the Irrawaddian and other sandy series give rise to extensive tracts of very light soil, almost pure sand. In the wetter parts of Burma, owing to the well marked dry season, a thick mantle of lateritic soil stretches over most of the lowland tracts.

Climate.

Burma forms part of the great Monsoon region of Asia, but its climate is profoundly modified by the relief of the country. There are really three seasons, the cool season, which is also rainless, sets in towards the end of October and lasts till February, the hot season (rainless) from March to the end of May or early June and the rainy season from June to October. October is an unpleasant month; the rains have almost ceased, but the temperature and humidity are high. Along the coast, and especially in the south (Tenasserim), both the daily and annual range of temperature are small. In Moulmein the annual range is 8° ; in Rangoon it is io°. Away from the moderating influence of the sea, the range of temperature increases greatly, and is especially large in the dry belt. The annual range in Mandalay is 2o°. The average temperature in the south of Burma is 8o°.From October to May Burma is under the influence of the north-east trade wind or the north-east monsoon as it is more often called. The north and south alignment of the mountains causes this wind to blow almost directly from the north. It is a cool wind, but decreases in intensity towards the end of the dry season. The change to the south-west monsoon is heralded by thunderstorms towards the end of May, but the rains do not usually break until about June 15. The south-west monsoon, blowing as it does from the Indian ocean, is the rain-bearing wind. A glance at a physical map will show that the coastal districts receive the full force of the wind, and a heavy rainfall in conse quence. Most of Arakan has nearly 2ooin. (5,i 2omm.) of rain. Rangoon enjoys an annual fall of 99.1 in. (2, 53 i mm.) . The heart of Burma lies in the lee of the lofty Arakan Yoma and the rainfall is scanty—as little as coin. in the heart of the dry belt. Mandalay lies in this dry region and receives an average of 33.4in. (855mm.). Owing to its elevation, the Shan plateau has a mod erately good rainfall.

Rivers and Lakes.

The rivers of Burma fall into three groups. There are numerous short, rapid streams, such as the Naaf, Kaladan, Lemru and An, which flow down from the Arakan Yoma into the Bay of Bengal. The centre of Burma is drained by the Irrawaddy (q.v.) and its tributaries, and by the Sittang. The Shan plateau is drained mainly by the Salween (q.v.) and its tributaries ; in Tenasserim there are again a number of short, rapid rivers flowing from the hills into the Gulf of Martaban. The longest is the Tenasserim river.The largest lake in Burma is a shallow stretch of water in the Federated Shan States, known as Inle lake. It is the remnant of a much larger lake ; is rapidly becoming smaller, and occupies a hollow in the surface of the plateau. A large lake known as Indawgyi, is found in the north of Burma near Mogaung. It has an area of nearly ioo sq.m. and, with the decreasing size of Inle lake, should perhaps be given pride of place. It is surrounded on three sides by ranges of hills, but is open to the north where it has an outlet in the Indaw river. In all the lowland tracts there are numerous small lakes occupying deserted river meanders. In the heart of the delta numerous large lakes or marshes, abound ing in fish, are formed by the overflow of the Irrawaddy river during the rainy season, but decrease in the dry season.

Vegetation.

The wide range of rainfall in Burma is respon sible for great variations in the natural vegetation. Frost never occurs in the lowlands, but roughly, above 3,000ft. the occasional frosts have caused a great change in vegetation. Above that level, which may conveniently be called the frost line, evergreen oak forests, sporadic pine forests and wide areas of open land, with bracken and grass, are the rule. Rhododendron forests occur at high levels. Below the frost line the natural vegetation depends mainly upon the rainfall: (a) With more than 8oin. of rain, ever green tropical rain forests occur. The trees of the forests are of many species, but more than one-half belong to the Diptero carpaceae. The timbers are hard and little used. (b) With be tween 4o and 8oin. of rain are the monsoon forests which lose their leaves during the hot season. These forests are the home of the valuable teak tree, as well as the pyinkado and other use ful timber trees. (c) With less than 4oin. the forest becomes very poor and passes into scrubland and semi-desert. There is little or no true grassland. (d) Extensive areas of the Irrawaddy delta are clothed with tidal forests, in which some of the trees reach a height of over r oof t., and are of considerable value.The wasteful methods of the native cultivator have, in the past, resulted in the destruction of vast areas of valuable forest. The practice was to cut down and burn a tract of virgin forest, cultivate the field (taung-ya) so formed for two or three years while the pristine freshness of the soil lasted and then to desert it for a fresh tract. It is but rarely that the forest established itself again over the deserted taung-ya ; more often the area became covered with a tangled mass of bamboo, bracken or grass. For more than half a century, however, the Forest Department has been at work, and all the valuable forests are constituted into Government reserves. Reserves covered 28,372 sq.m. in 1926. Various privileges are accorded to the natives who live within the reserved area. The timber (mainly teak for constructional work and pyinkado—Xylia dolabri f ormis—f or railway sleepers) , is worked either by Government or by lessees--public and private companies—under careful supervision. Extraction is so controlled that it shall not exceed regeneration. The output of teak in 1925-26 was 339,526 tons, and of other reserved timbers 163,318 tons. Timber is third in importance amongst the exports of Burma, and for some years past the annual exports have been roughly 150,000 tons annually; worth about £r,5oo,000. More than half Burma is forested.

Fauna.

The anthropoid apes are represented by two gibbons, and there are about a dozen species of monkeys. Tigers are still common throughout the province; leopards and several species of wild cat also occur. The Himalayan black bear and the Malayan bear are found in the hills. Bats are numerous and the huge flying fox is particularly common in several of the large towns. Amongst the hoofed quadrupeds, the elephant is still numerous in many of the denser forests, and numbers are caught annually in "keddahs" and trained for forest work. Two species of rhinoceros occur, but are now far from common. Amongst wild oxen and deer the saing or wild buffalo is common, and so is the banting. The small barking deer (gyi) is the commonest of the larger animals and is still abundant almost everywhere. The tliamin, sambhuar and hog-deer are also common. A licence is required for hunting most of the larger animals, and many of them enjoy a "close season." The half-wild pariah or "pi" dogs swarm in every village. Amongst the numerous birds, the bright hued small parrots may be specially noted, and the ubiquitous paddy bird. Crows are exceedingly abundant and very bold. A characteristic lizard is the house gecko or taukte (so called be-, cause it makes a loud croaking noise like taukte, repeated four to ten times) . Snakes, including the python, are numerous.

Natural Regions.

For an adequate study of this large and varied province, a division into at least seven natural regions is desirable : (I) The Arakan coastal strip is hilly or mountain ous, has a very heavy rainfall and is covered with the remnants of a dense evergreen forest which has, however, been largely replaced by dense bamboo thickets. This region is sparsely inhab ited, and the population is concentrated round the principal town and port of Akyab. Communication with the rest of Burma is difficult, except by sea. The region coincides roughly with the districts of Akyab, Kyaukpyu, Sandoway and the western strip of Bassein. (See ARAKAN and AKYAB.) (2) The Tenasserim coastal strip is similar, but is of importance as the tin and wolfram producing region. Rubber plantations are increasing in impor tance. Moulmein is the chief town. The region coincides roughly with the districts of Mergui, Tavoy, Amherst, Thaton and Sal ween. (See TENASSERIM and MOULMEIN.) (3) The Western hills region consists of the mountainous, almost uninhabited, tracts of the Arakan Yoma and its hill ranges. Such districts as the hill district of Arakan, Pakokku hill tracts, Chin hills and Somra tract, lie wholly within this region. (4) The Northern hills region occupies the north of the country and includes the sources of the Irrawaddy and its principal tributary, the Chindwin. The region is as yet little developed. It includes the districts of Upper Chind win, Myitkyina, Katha and most of Bhamo. (5) The dry belt occupies the heart of Burma. It is a flat and fairly thickly popu lated region, extensively cultivated and having some irrigated areas. The oilfields, with one exception, lie in this region. It coincides, roughly, with the districts of Lower Chindwin, Shwebo, Sagaing, Mandalay, Pakokku, Myingyan, Meiktila, Minbu, Mag we, Thayetmyo and Yamethin. (6) The deltas region, includ ing the deltas of the Irrawaddy and Sittang rivers and the inter vening forested ridge of the Pegu Yoma, is the most important and the most thickly populated part of Burma. It includes the districts of Hanthawaddy, Pyapon, Maubin, Myaungmya, most of Bassein, Henzada, most of ,Prome, Tharrawaddy, Insein, Pegu and Toungoo. (7) The Shan plateau was, until recently, cut off in a remarkable way from the rest of Burma, and still preserves many distinctive features. The region coincides, roughly, with the Federated Shan States.Burma is essentially a rural country. Only two towns have over 1oo,000 inhabitants—Rangoon with 341,962, and Mandalay with 148,917. The smaller towns are river ports, collecting and distributing centres, or have achieved some importance from having been chosen as the headquarters of a district. The dry belt is the natural geographical centre of Burma and therein lie the old Burmese capitals—Pagan, Shwebo, Ava, Amarapura and Mandalay, with Prome on the southern borders of the dry belt.

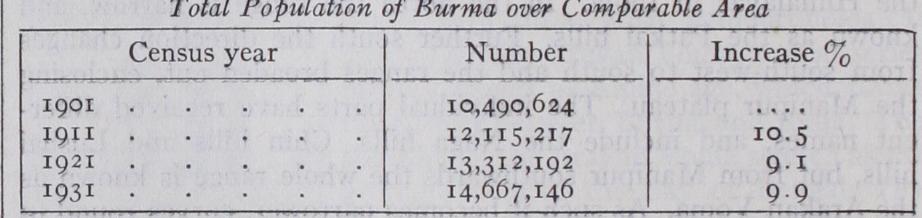

Population.

Burma's population (1931 census) was 14, 667,146.

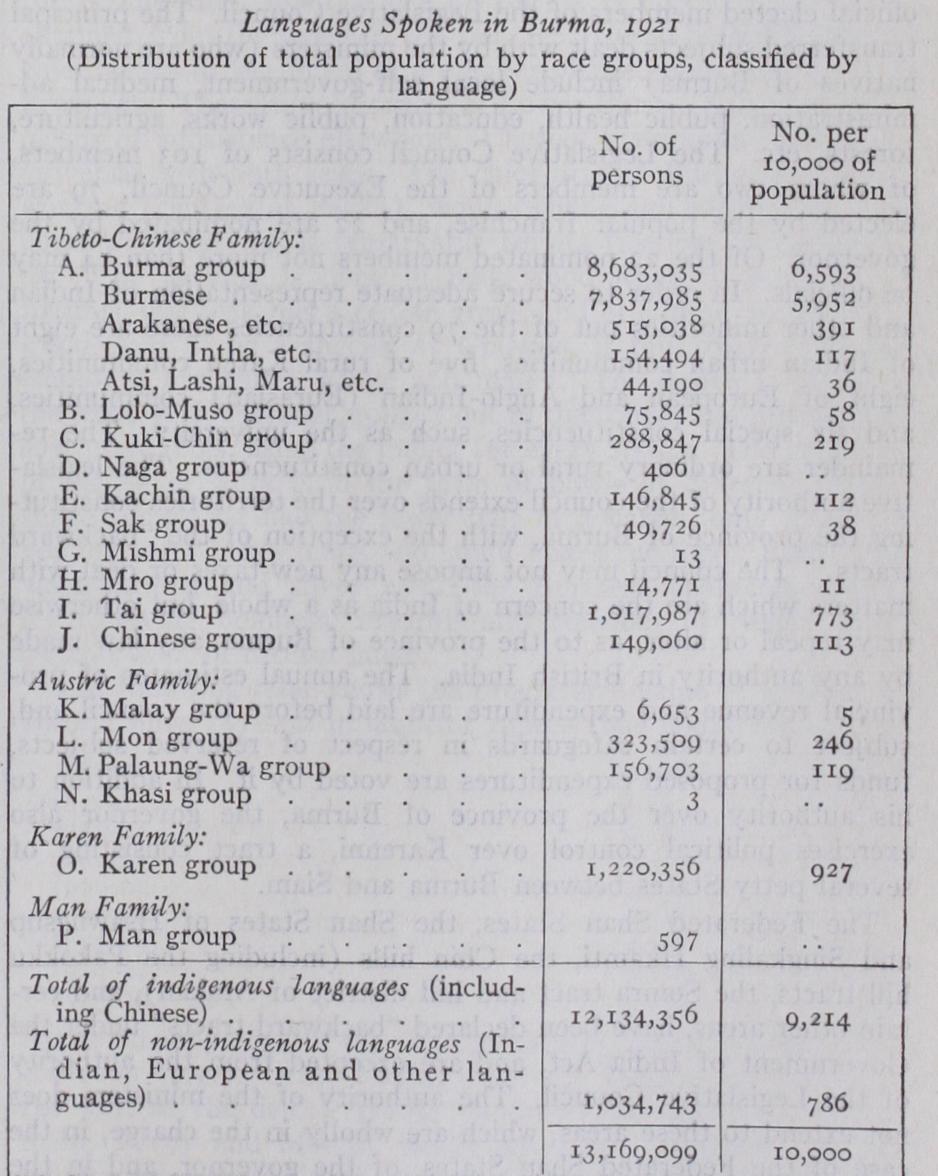

The inhabitants of Burma belong to many races and speak many languages. In general, the native races are all Mongolians; the Burmans are the most advanced, and occupy the fertile low lands; the other races are restricted to the hills. Every year large numbers of Indians are attracted to Burma by the higher rates of wages, and the opportunities for trading and cultivation. A considerable proportion of the Indian immigrants settle per manently. Burma is in the interesting position of being an under populated country, capable of considerable development, lying between two of the most densely populated countries in the world --*India and China. It is believed that Burma has been populated by successive waves of migration from the north ; indeed the advance of the Kachin races was still in progress when Burma was annexed to the British empire. The Burmans, including the closely allied Arakanese of the Arakan coast, the Talaings of the country around Moulmein, and the Tavoyans around Tavoy, number more than r I millions. The national dress is a cylin drical skirt, called a lungyi, worn folded over in a simple fold in the front and reaching to the ankles. All Burmese, of both sexes, prefer silks of bright but delicate shades, and even the poorest possesses at least one silk lungyi. The distinctive silk, woven in the district round Mandalay, is still in general use. The lungyi is worn by both sexes, the men wear also a single breasted short jacket of sombre hue, called an aingyi; the women's garment is similar but double breasted and usually white. The older generation of Burmese men wear their straight black hair long, tied in a knot on one side of the head. It is now general to cut the hair in European style. The men's head-dress is a gambaung —a strip of brightly-coloured thin silk wound round the head. The women oil their long tresses with coconut oil and coil them in a cylindrical coil on the top of the head.

The Burmans are Buddhists, and their religion occupies a large place in their life. The spiritual head of every village is the yellow-robed Hpoongyi, or monk. The monastery, or hpoongyi kyaung just outside the village walls—all Burmese villages are surrounded by a fence against wild animals and robbers—is also the village school. Every village has its pagoda, a silent remainder of the precepts of Buddha, and the whitewashed pagodas crown almost every hill, but there are no temples in the ordinary sense of the word. As a result of the numerous village schools, the per centage of wholly illiterate men is small. The women are more industrious and business-like than the men, but their school educa tion has been neglected. The Burmese women enjoy an amount of freedom unusual in non-European races. As a whole the Burmese are characterized by cleanliness, a sense of honour and a love of sport, but addicted to a life of ease and laziness. The various hill tribes are, in general, less advanced than the Burmese. Per haps the most advanced are the Karens, who inhabit the Arakan Yoma, the Pegu Yoma and the native State of Karenni, and are also found as scattered communities in the delta. The Shans occupy most of the Shan plateau and are also found in the upper part of the Chindwin valley. The Kachins belong mainly to the far north, the Chins to the western mountains, whilst on the Chinese borders are found the Palaungs, Was, etc. Some of the latter are still addicted to the barbarous practice of head hunting. All the hill tribes of Burma are non-Buddhists, being for the most part Animists. Christianity has made rapid strides amongst them, especially amongst the Karens.

The Indians have settled mainly in the delta regions, in Arakan and along the rivers and railway lines. Except in the remoter districts, Indians supply nearly all the coolie labour, whilst the indolent habits of the Burman often result in his falling into the clutches of the Indian moneylender. There are now roughly a million Indians in Burma, drawn mainly from Madras, Behar and Orissa and Bengal. The Chinese form an important community. Except on the border in the north-east, where the Yun nanese and Chinese Shans are found, the Chinese belong essentially to the artisan and merchant classes, and make excellent law-abiding citizens.

Europeans, mainly English and Scotch, number rather less than 1 o,000 ; very few can be regarded as permanent residents.

Eurasians (now officially termed Anglo Indians) number about ro,000. The Eura sians find employment as clerks in minor administrative capacities, and on the rail ways.

Religion.

The chief religious prin ciple of the Burman is to acquire merit for the next re-incarnation by good works done in this life. The bestowal of alms, offerings of rice to priests, the founding of a monastery, the erection of a pagoda or the building of a rest house (zeyat) for travellers, are all works of religious merit. An analysis shows that less than two in every thousand Burmans profess Christianity, and there are one per thousand of Mohammedans among them. It is admitted by the missionaries themselves that Christianity has progressed very slowly amongst the Burmans in comparison with the rapid progress made amongst the Karens. It is amongst the Sgaw Karens that the greatest progress in Christianity has been made, and the number of Animists among them is very much smaller. The num ber of Burmese Christians is considerably increased by the in clusion among them of the Christian descendants of the Portuguese settlers of Syriam deported to the old Burmese Tabayin, a village now included in the Ye-u sub-division of Shwebo. These Chris tians returned themselves as Burmese. The forms of Christianity which make most converts in Burma are the Baptist and Roman Catholic faiths.

Education.

Education, apart from the old established monas tic schools, is controlled by the Education Department. There are primary, middle and high schools, divided into two groups; the English schools mainly for Anglo-Indians, in which the medium of instruction is English, and the Anglo-vernacular schools, in which the medium of instruction is usually the ver nacular in the lower standards and English in the higher standards. In 1925-26 there were 6,694 institutions, with 411,398 pupils. A university with two colleges, one Christian and one non-re ligious, has been constituted at Rangoon since 192o; formerly the Rangoon college was a constituent college of Calcutta university.The Burmese language is a monosyllabic, agglutinative language, more closely allied to Chinese than to the Indian languages. A single syllable may have six or more meanings, according to the tone used or to the way in which the syllable is stressed. Many dialects and languages belonging to the Burmese group are dis tinguished, quite apart from the entirely distinct languages spoken by the Shans, Kachins, Karens and other hill tribes. Burmese and English are the official languages. Hindustani is widely spoken wherever Indian labour is employed.

Note: There is an increasing tendency for Burmese to become the language of people belonging racially to such groups as Kuki-Chin, Kachin and Tai.

The Burmans adopted alphabets borrowed from the old, rock cut Pali of India. Thus their alphabet, their religion and a con siderable number of words, are of Indian origin. Burmese music is distinctive; their melodies are mainly composed of the five notes, C, D, E, G, A ; they do not use semitones, so the chro matic scale is unknown. Music is essentially associated with the drama. Characteristic instruments include the kyi-waing, a series of gongs cast out of bell metal, arranged in a circular frame of stout cane and the saing-waing, composed of 18 cylindrical drums hung from a circular frame.

Government.

The divisions of Arakan and Tenasserim were annexed to the British empire after the First Burmese War in 1826; Pegu after the Second Burmese War in 1853. These three divisions constitute Lower Burma. Upper Burma was annexed in 1886 after the Third Burmese War. As a province of India, Burma comes under the Central Government of India, and so under the secretary of State for India in London. At the head of the Provincial Government of Burma is the governor. In accordance with the policy of the British Government in giving a large measure of self-government to the native races of India, native ministers have, since Jan. 1923, played an important part in government. An excellent summary of the present form of administration is given in the Report on the Administration of Burma for the Year 1921-22. With effect from Jan. 2, 1923, the province of Burma was constituted a governor's province under the Government of India Act. The executive authority of Govern ment vests in a governor in council in respect of a small number of subjects known as reserved subjects, and in the governor act ing with ministers in respect of subjects known as transferred subjects. The governor and the two members of his executive council (one of whom must have been for at least 12 years in the service of the Crown in India) are appointed by the King by warrant under the royal sign manual. The ministers also number two, and are appointed by the governor from among the non official elected members of the Legislative Council. The principal transferred subjects dealt with by the ministers (who are normally natives of Burma) include local self-government, medical ad ministration, public health, education, public works, agriculture, forests, etc. The Legislative Council consists of 103 members, of whom two are members of the Executive Council, 79 are elected by the popular franchise, and 22 are nominated by the governor. Of the 22 nominated members not more than 14 may be officials. In order to secure adequate representation of Indian and other minorities out of the 79 constituencies there are eight of Indian urban communities, five of rural Karen communities, eight of European and Anglo-Indian (Eurasian) communities, and six special constituencies, such as the university. The re mainder are ordinary rural or urban constituencies. The legisla tive authority of the council extends over the territories constitut ing the province of Burma, with the exception of the "backward tracts." The council may not impose any new taxes or deal with matters which are the concern of India as a whole, but otherwise may repeal or alter, as to the province of Burma, any law made by any authority in British India. The annual estimates of pro vincial revenue and expenditure are laid before the council and, subject to certain safeguards in respect of reserved subjects, funds for proposed expenditures are voted by it. In addition to his authority over the province of Burma, the governor also exercises political control over Karenni, a tract consisting of several petty States between Burma and Siam.The Federated Shan States, the Shan States of Hsawngsup and Singkaling Hkamti, the Chin hills (including the Pakokku hill tracts, the Somra tract and hill district of Arakan), and cer tain other areas, have been declared "backward tracts" under the Government of India Act, and are excepted from the authority of the Legislative Council. The authority of the ministers does not extend to these areas, which are wholly in the charge, in the case of the Federated Shan States, of the governor, and in the case of the "backward tracts," of the governor in council. A special personnel for the administration of the "backward tracts" is pro vided by the Burma Frontier Service.

The province is at present divided into eight divisions, each in charge of a commissioner, they are Arakan, Pegu, Irrawaddy, Tenasserim, Magwe, Mandalay, Sagaing and the Federated Shan States. The commissioners are responsible to the governor in council, each in his own division, for the working of every de partment of the public service except the military department and part of the judicial department. The divisions are further divided into districts (of which there are about 4o) each in charge of a deputy commissioner. Deputy commissioners perform the func tions of district magistrates, collectors, registrars and sometimes of assistant commissioners of income tax and district judges. Subordinate to the deputy commissioners are assistant commis sioners, extra assistant commissioners and myooks. The myooks or township officers are drawn from the ranks of the subordinate civil service and are the ultimate salaried representatives of Government who come into most direct contact with the people. The extra assistant commissioners are members of the Burma Civil Service; higher officials are members of the Burma Com mission and are mostly officers of the Indian Civil Service. Finally there are the village headmen or thugyis,, chosen by the villagers and approved by Government, who have limited magisterial powers and collect the thathmeda or head tax.

The land and revenue administration of the province is con trolled by a financial commissioner assisted by a secretary. Under the control of the financial commissioner are the Excise Depart ment (dealing with opium and salt), customs, settlements and land records. The High Court of Judicature at Rangoon was estab lished in 1922. It consists of a chief justice and seven other judges. In 1925 the Province was divided into 23 session divi sions. The activities of the Government in connection with agri cultural and industrial development are under the control of a development commissioner, subordinate to whom are the Depart ment of Agriculture, the Rangoon Development Trust, the co operative societies registrar and the veterinary adviser. The Public Works Department is under the control of chief engineers for buildings, roads and irrigation. The Police Department is under the control of an inspector-general; the military police (used mainly in frontier tracts) are under a deputy inspector general. The Forest Department is administered by a chief con servator of forests and the province is divided into a number of "circles," each under a conservator, assisted by officers of the Indian, provincial and subordinate forest services. (For details regarding the administration of the Federated Shan States see