Economics and Trade

ECONOMICS AND TRADE Bulgaria consists of two mountain ranges, the Balkans and the Rhodopes, and two valleys. The Balkans run just north of her central line, almost due east and west, and the Rhodopes, break ing off from them on Bulgaria's western frontier, curve round in a south-easterly sweep until they straighten out again so as to run almost parallel with the Balkans above them. Between these two ranges is enclosed the valley of the Maritsa, which gradually widens out towards the Black sea as the Maritsa leaves it and twists southwards to its outlet at Dedeagatch. As a result largely of the mountainous character of the country the proportion of the total area (1 o3,146sq.km.) used for agricultural purposes is only about 38%. Over a third of the area is covered by forest and over 27% is wholly unproductive. But of this forest land a large part is unproductive scrub, and many of the real forests are in accessible. Indeed, the wood imports into Bulgaria exceed her exports. The area immediately available for the production of wealth in Bulgaria is, therefore, small, and although the soil in certain districts is extremely rich the agricultural production and the wealth of the country are both low. Over 8o% of the popula tion are engaged in agricultural pursuits, and such industries as exist (flour-milling, spinning and weaving, cigarette manufacture, etc.) are relatively unimportant.

Agriculture.

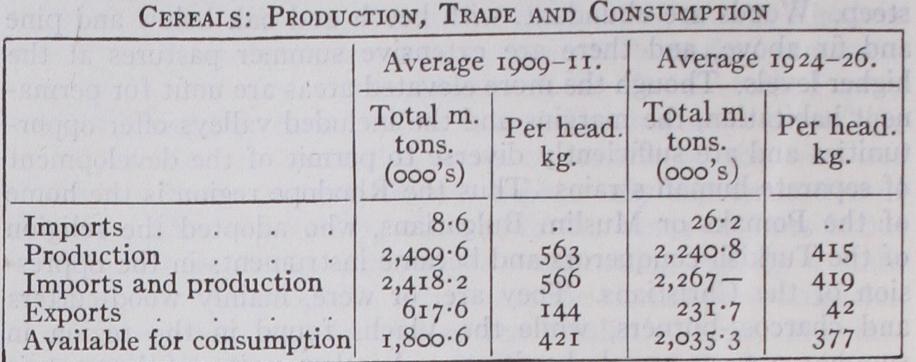

Until 1879 Bulgaria was under Turkish domi nation. Between 191I and 1918, with but brief intervals, she was at war. The land, except the communal pastures and the for ests, is owned by the peasants, and there are no large holdings. As a result of these facts the system of agriculture in Bulgaria remains extremely primitive. A large proportion of the ploughs used are made of wood; corn is usually sown by hand; artificial fertilizers are not used, and farm manure only to a very restricted extent.Before the World War, wheat was at once the most important agricultural product and article of export. In 1910 over a mil lion hectares were devoted to its cultivation ; the crop amounted to 1,148,00o metric tons, and exports, including wheaten flour, to about 300,00o metric tons. Great changes followed the war. Between 1910 and 1923 the area under cereals dropped by 13%, while that devoted to tobacco rose from 7,800 to 6o,000 hectares. Before the Treaty of Bucharest the tobacco industry in Bulgaria was of quite minor importance. The rapid increase in prices dur ing the war, however, stimulated its cultivation, and after the Armistice, Bulgaria seized the opportunity which the continuation of hostilities between Greece and Turkey afforded her, and rapidly expanded the acreage devoted to tobacco. Her post-war economic recovery must largely be attributed to this fact. But after the final settlement at Lausanne of the war between Turkey and Greece, and the revival of these two countries as producing areas, the supply of oriental tobacco became excessive, and the acreage under this crop in Bulgaria had sunk by 1927 to 26,000 hectares. As the tobacco area shrank more land was devoted to cereals, cotton, sugar-beet and other industrial crops, more especially oleaginous plants. But the area under cereals in 1927 was still 6% lower than in 191o. Meanwhile the population grew, partly on account of the immigration of refugees, from 4,338,00o in 1910 to 5,483,000 in 1926. As the total production of cereals in 1927 was somewhat lower than it was before the outbreak of the Balkan wars, the production per head and in consequence the exportable surplus has been seriously reduced. The extent of the change which has taken place may be judged from the following summary figures: In view of this reduction in the available surplus of corn, con siderable importance must be attached to the endeavour to pro mote the cultivation of higher value crops such as sugar-beet, cotton, sesame seed, etc. These crops are not intended so much to replace cereals as export articles, as to supply the domestic re quirements and hence lessen the necessity for import.

Of still greater importance, however, are the attempts which are being made to increase the production per hectare by the intro duction of modern machinery, the improvement of methods of agriculture, the establishment of model farms, and the improve ment of stock by cross-breeding.

Owing to the configuration of the land, Bulgaria is well adapted for a mixed system of agriculture, the mountain slopes affording adequate pasturage for a considerable head of beasts. Her herds and flocks are in fact large, and she has more sheep in proportion to her population than any other country in Europe. Although the most recent statistics relate to 1920, there is reason to believe that the numbers of her livestock are considerably greater than they were immediately before the World War. The cattle, how ever, are mainly used for draught purposes, and the export of meat and live animals is smaller now than it was in 1910 or 1911.

Industry and Mining.

As already stated, the industries in Bulgaria are of minor importance, and with three exceptions— the preparation of tobacco leaf, the distillation of attar of roses, and flour-milling—they are confined to the domestic market. In 1926 the total capital of the so-called "large industries"—this term excludes tobacco and rose oil which are grouped with agri culture—amounted to just under £4,000,000. But the peasant himself supplies most of his own requirements, spinning and weaving his own textiles and making his own shoes.Although the country is reported to be rich in minerals, the only mines of importance are those of soft coal, which are almost all owned by the State. Of the total output in 1926, viz., I,I 14,000 metric tons, only 147,500 metric tons were extracted from pri vate mines. The total production is adequate to meet the needs of the country and even to allow a small surplus for export when prices are favourable. In addition, small quantities of copper and lead ore are mined.

Trade.

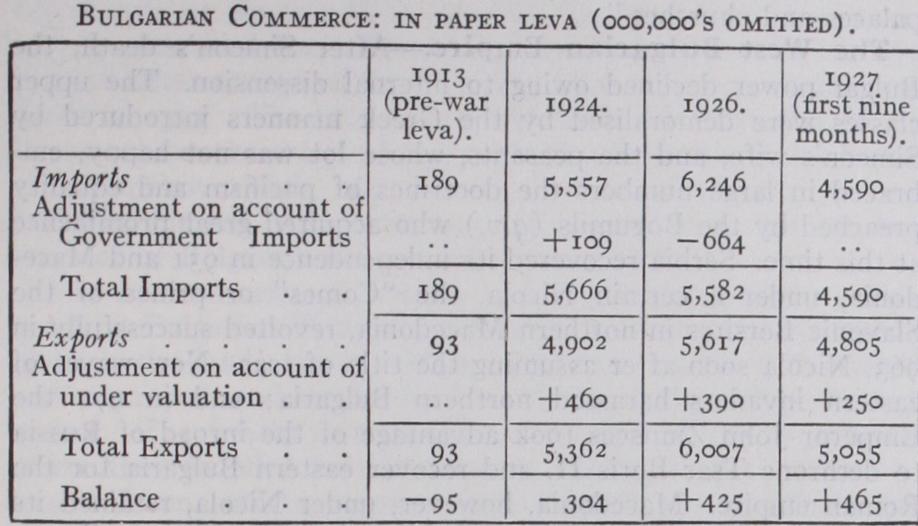

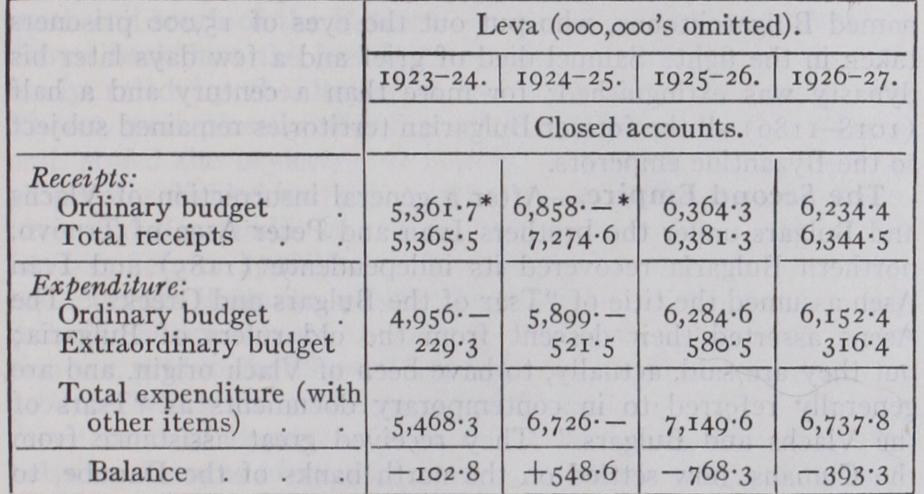

The international trade of Bulgaria necessarily con sists of the exchange of agricultural products for cheap manufac tures. Just under one-third of her imports consists of textiles, mainly for the town population, and about one-third of machinery —largely agricultural—and other manufactures of metals. The composition of her exports has undergone considerable changes owing to the increase in the importance of tobacco and the falling off in the available supply of cereals. In 1910 cereals accounted for nearly 6o% of the total exports by value, and in 1924-26 for only about 33%. The most important drop was in wheat, from about 3o% to 5% or less. On the other hand tobacco leaf, which in 1910 represented less than 2%, amounted in 1924 to 32%, in 1925 to 41% and in 1926 to 37% of total values.The published statistics of Bulgarian trade must be read with considerable caution, as owing to the system of valuation em ployed the real value of her exports is understated. Moreover, confusion has been caused by the inclusion in the 1926 statistics of a considerable quantity of imports on Government account which were actually paid for in earlier years. If allowances be made on these two accounts the following approximate results are obtained: Public Finance.—In the following table are shown the revenue and expenditure for the financial years 1923-24 to 1926-27: *Including gross receipts from the Pernik mine. If, as in the budgets for the following financial years, only net receipts be included, the total ordinary revenue in 1924-25 would be about 6,65o million leva.

In June 1922 a law was passed limiting the advances which the State might obtain from the national bank to 4.7 milliard leva, and about the same budget equilibrium was established. In the financial year 1924-25 the ordinary revenue, after excluding the gross receipts of the Government coal-mine, amounted to as much as 6,65o million leva. But in the following year the country was affected by the fall in the prices of agricultural products and the general economic difficulties which characterized this period. Hence revenue fell off, while expenditure, in view of the favour able results of the previous year, had been increased to 7,15o million leva. There resulted a deficit of 768.3 million leva, and vigorous measures were taken in 1926 and more especially 1927 to reduce expenditure and re-establish the finances on a sound basis.

According to the settlement reached in March 1923 the repara tions debt was fixed at 2,25o million gold francs divided into two blocks. Block B, which is by far the greater, amounting to 1,700 million gold francs, bears no interest and on it no payments are due until April 1953. Payments on account of block A rise from 10 million gold francs in 1927-28 to 20 million in in and 43.4 thereafter until 1982-83. The total pay ments on account of all forms of foreign debt on which a settle ment had been reached amounted in 1927-28 to 31.7 million gold francs. Of the total domestic debt of 4,768 million leva (176.7 million gold francs) 4,516 million leva were in Sept. 1927 due to the national bank.

In 1926 a loan was raised of £3,300,000 for the settlement of the refugees from neighbouring lands, a general scheme of settle ment having been elaborated by the League of Nations. This scheme differs from the parallel undertaking in Greece inasmuch as the majority of the refugees are placed in existing villages and not in new colonies. Their gradual return to production should do much to accelerate the economic development of the countryside.

The Economic Mechanism.

In a country divided by mountain ranges, with relatively sparse railway connection and bad roads, with a peasant population which has not yet enjoyed half a century of independent national life, economic progress must necessarily depend largely on the tutelary activity of its Government, and the economic mechanism is likely therefore to be State-controlled. So in Bulgaria the railways and the coal mines belong to the State, and the two most important credit in stitutions, the national bank and the agricultural bank, as indeed also the co-operative bank, are State institutions. The agricultural bank supplies credit against crops, stock or personal guarantee to the peasants or the agricultural co-operative societies, having a considerable number of branches scattered throughout the coun try. The central co-operative bank centralizes the credit activities of the institutions dealing with the productive and wholesale co operative societies. As a general rule the agricultural co-operatives are based on the Raiffeisen, and the others on the Schultze Delitz system.The ancient Thraco-Illyrian race which inhabited the district between the Danube and the Aegean, were expelled or absorbed by the great Slavonic immigration which lasted from the 3rd to the 7th century A.D. The many tumuli found in all parts (see Herodotus v. 8) and some stone tablets with bas-reliefs re main as monuments of the aboriginal population, and certain structural peculiarities, common to the Bulgarian and Rumanian languages, are perhaps due to the influence of the primitive Il lyrian speech. The Slays, an agricultural people, were governed, even in those remote times, by the democratic local institutions to which they are still attached; they possessed no national leaders or central organization and their only political unit was the "pleme," or tribe. They were considerably influenced by contact with Roman civilization. It was reserved for a foreign race, al together distinct in origin, religion and customs, to give some unity and coherence to the scattered Slavonic tribes.

The Bulgars.

The Bulgars, a Turanian race, akin to the Huns and Avars, belonged to the wave of migrants which came ward behind the Huns. They were a horde of wild horsemen, fierce and barbarous, and governed despotically by their khans (chiefs) and boyars or bolyars (nobles). Their religion, about which little is known, was probably polytheistic, although some of them had certainly embraced Islam. Men and women wore baggy trousers, and the women veiled their faces, while the men wore large turbans over heads shaven clean. Their principal food was meat, and they lived by and from war. In the 4th century the Bulgars had reached the steppes tween the Urals and the Volga; by in A.D. 433, their federation split into two groups —the Utiguri and the Kutriguri. The latter were at first the more powerful. For Ioo years they formed a strong state on the north coast of the Black sea, whence they formed a continual menace to the eastern Roman empire. About A.D. 56o this state was annihilated by the Avars, who absorbed the survivors into their ranks, and herewith the guri disappear from history. The Utiguri, living farther eastward, were subject only a few years to the Avars, and after these had passed on, to the Turks. In A.D. 582 they recovered their independence and founded a state on the Volga, remains of which survived into the 13th century under the name of Great (or Black) Bulgary. A tribe of Utiguri, under their khan paruch, or Isperich, moved westward, before the pressure of the expanding Khasar state, crossed the Danube in 679 and, after subjugating the Slavonic population of Moesia, advanced to the gates of Constantinople and Salonika. The east Roman emperors were compelled to cede to them the province of Moesia and to pay them an annual tribute. The invading horde was not numer ous, and during the following centuries it became gradually merged in the Slavonic population. Like the Franks in Gaul, the Bulgars gave their name and a political organization to the more civilized race which they conquered and whose language, customs and local institutions they adopted. No trace of the original Bul garian tongue remains in the language now spoken in Bulgaria.

Early Dynasties.

The early Bulgarian state lay along both banks of the Danube, although the suzerainty of their khans over the northern bank, which at the time was practically a no-man's land, was probably always shadowy. Khan Krum (802-804) and his son Omortag (814-830 succeeded to the heritage of the Avars in much of eastern Hungary and Transylvania, but with the arrival of the Magyars and Petchenegs (q.v.) at the end of the 9th century, all territory north of the Danube was abandoned and even the southern half of the Danube valley was depopulated by raids and filled with alien races who settled there in considerable number. The expansion of the Bulgar empire southward was more lasting. In numerous campaigns against Byzantium, the Bulgar khans gradually extended their frontiers, and Kardam (777-802) and Krum again exacted the tribute paid to Asparukh. Khan Krum waged a desperate campaign against the emperor Nice phorus, who invaded Bulgaria and burned Preslav; but Krum annihilated the army as it returned through the Balkan passes (811), slew the emperor and converted his skull into a drinking goblet. In following years he devastated Thrace "like a new Sennacherib" and besieged Constantinople itself, and the city was only saved by his sudden death. Khans Pressian (836-853) and Boris (857-888) extended the frontier of Bulgaria far to the south-west, to include Debar, Okhrida and all the upper Struma valley, as well as the Morava valley on the west. The great majority of the enlarged Bulgarian state was now almost purely Slavonic ; and for 30o years, while the whole of north-eastern Bulgaria was repeatedly ravaged by Russians, Magyars, Petch enegs and Cumans, the Slavonic centre and the south-west was to become even more the centre of gravity of the Bulgarian state. This process was accelerated by the official introduction into Bul garia of Christianity by the disciples of the "Apostles of the Slays," S. S. Cyril and Methodius. The adoption of the Slavonic or "Old Bulgarian" language as that of the official liturgy was the final stage in the assimilation of the original Bulgar race. Boris probably adopted Christianity from political motives, although according to legend he was frightened into it by the ghastly pic tures of Hell painted on his palace walls by a Byzantine monk, and he ended his own days in a monastery. The great controversy between Rome and Byzantium regarding the Patriarch Phocas had broken out in 86o. Boris long wavered between the rival churches, but when the Pope failed to fulfil the hope that he had held out of granting Bulgaria an independent and national Patriarch, Boris, in 870, decided for the Eastern Church. The decision was fraught with momentous consequences for the future of his country. The nation altered its religion in obedience to its sovereign, and some of the boyars who resisted the change paid with their lives for their fidelity to the ancient belief. The independence of the Bulgarian Church was recognized by the Patriarch, a fact much dwelt upon in recent controversies. The Bulgarian primates subse quently received the title of Patriarch; their see was transferred from Preslav to Sofia, Voden, and Prespa successively and finally to Okhrida.

The First Empire.

The national power was at its zenith under Simeon (893-927), a monarch distinguished in the arts of war and peace. In his reign, says Gibbon, "Bulgaria assumed a rank among the civilized powers of the earth." It was under Simeon that the trans-Danubian possessions were finally lost, but he extended his frontiers to the Adriatic in the south-west and also brought the Serbs under his sway, which now reached as far as the Sava and the Drina. Having become the most powerful monarch in eastern Europe, Simeon assumed the title of "Emperor and Autocrat of all the Bulgars and Greeks," a style which was recognized by Pope Formosus. He aspired, however, to a higher title still. His numerous campaigns against Byzantium were prompted by the ambition to place on his head the Imperial crown; and his pursuit of this dream left his country nearly ex hausted. While he reigned his people made great progress in civilization, literature flourished, and his capital Preslav is reputed as rivalling Constantinople in magnificence, and full of "high palaces and churches." The West Bulgarian Empire.—Af ter Simeon's death, the Bulgar power declined owing to internal dissension. The upper classes were demoralised by the Greek manners introduced by Simeon's wife, and the peasants, whose lot was not happy, em braced in large numbers the doctrines of pacifism and equality preached by the Bogumils (q.v.) who acquired great prominence at this time. Serbia recovered its independence in 931 and Mace donia, under a certain Nicola, the "Comes" or prince of the Slavonic Bersites in northern Macedonia, revolted successfully in 963, Nicola soon after assuming the title of tsar. New waves of eastern invaders harassed northern Bulgaria; and in 972 the Emperor John Zimisces took advantage of the inroad of Russia to dethrone Tsar Boris II. and recover eastern Bulgaria for the Roman empire. Macedonia, however, under Nicola, retained its independence, and Nicola's son Samuel (980-1014), actually re covered Serbia and northern Bulgaria for this new "Bulgarian" empire, and extended his power southward to Thessaly; but in 1014 he was defeated at Belasitsa by the emperor Basil II., sur named Bulgaroktonos, who put out the eyes of 15,000 prisoners taken in the fight. Samuel died of grief and a few days later his dynasty was extinguished ; for more than a century and a half (1o18-1186) all the former Bulgarian territories remained subject to the Byzantine emperors.

The Second Empire.

Af ter a general insurrection of Vlachs and Bulgars under the brothers Ivan and Peter Asen of Trnovo, northern Bulgaria recovered its independence (1185) and Ivan Asen assumed the title of "Tsar of the Bulgars and Greeks." The Asens asserted their descent from the old rulers of Bulgaria; but they are said, actually, to have been of Vlach origin, and are generally referred to in contemporary documents as "Tsars of the Vlachs and Bulgars." They received great assistance from the Cumans, now settled on the north banks of the Danube, to whom they were allied by treaty and marriage. Kaloyan, or Joanitsa, the third of the Asen monarchs, extended his dominions to Belgrade, Nish, and Skoplje; he acknowledged the supremacy of the Pope who, in his own words, "extolled him above all other Christian monarchs," received the royal crown from a papal legate and was certainly the strongest party in the three-cornered war fare which was waged for many years between the Byzantine empire, the Crusaders (at that time established in Constanti nople), and the Bulgars. The greatest of all Bulgarian rulers was Ivan Asen II. (1218-41) a man of humane and enlightened character. Af ter a series of victorious campaigns he established his sway over Albania, Epirus, Macedonia and Thrace, and governed his wide dominions with justice, wisdom and moderation. In his time the nation attained a prosperity hitherto unknown ; commerce, arts and literature flourished. Trnovo, the capital, was enlarged and embellished, and great numbers of churches and monasteries were founded or endowed. At this period, to judge from the chronicles of the Crusaders, Bulgarian civilization was on a level with that of Europe. The dynasty of the Asens became extinct in 1280. None of their successors were able to establish a strong central authority, and feudal anarchy prevailed. Further, northern Bulgaria was repeatedly ravaged by the invasions of Mongols, to whom it was vassal in 1292-95. Two other dynasties, both of Cuman followed—the Terterovtsi, who ruled at Trnovo, and the Sismanovtsi, who founded an independent state at Vidin, but afterwards reigned in the national capital. Eventu ally, on July 28, 1330, Tsar Michael Sisman was defeated and slain by the Serbians, under Stephen Uros III., at the battle of Velbuzhd (Kustendil). Bulgaria, though still retaining its native rulers, now became subject to Serbia, and formed part of the short-lived empire of Stephen Dusan (1331-56). The Serbian hegemony vanished after the death of Dusan, and the Christian races of the Peninsula, distracted by the quarrels of their petty princes, fell an easy prey to the Muslim invader.In 1340 the invading Turkish forces had begun to ravage the entire valley of the Maritsa; in 1362 they captured Philippopolis, and in 1382 seized Sofia. In 1366 Ivan Sisman III., the last Bulgarian tsar, was compelled to declare himself the vassal of the Sultan Murad I. In 1389 the rout of the Serbians, Bosnians and Croats at Kosovo Polje decided the fate of the Peninsula. Shortly afterward Ivan Sisman was attacked by the Turks; and Trnovo, after a siege of three months, was captured, sacked and burnt in 1393. The fate of the last Bulgarian sovereign is un known : the national legend represents him as perishing in a battle near Samokov. Vidin, where Ivan's brother, Srazhimir, had es tablished himself, was taken in 1396, and with its fall the last remnant of Bulgarian independence disappeared.

The five centuries of Turkish rule (1396-1878) form a dark epoch in Bulgarian history. The invaders carried fire and sword through the land; towns, villages and monasteries were sacked and destroyed, and whole districts were converted into desolate wastes. The inhabitants of the plains fled to the mountains, where they founded new settlements. Many of the nobles em braced Islam ; others, together with numbers of the priests and people, took refuge across the Danube. Among the people only the Bogumils adopted Islam in large numbers : the Pomaks of the Rhodopes were converted only in the 17th century. Large colonies of true Turks were, however, settled in the plains both north and south of the Balkans, the true Bulgarian element being driven back into the less fruitful districts. All the regions for merly ruled by the Bulgarian tsars, including Macedonia and Thrace, were placed under the administration of a governor gen eral, styled the beylerbey of Rumili, residing at Sofia; Bulgaria proper was divided into the sanjaks of Sofia, Nikopolis, Vidin, Sil istria and Kiustendil. A new feudal system replaced that of the boyars; fiefs or spahiliks were conferred on the Ottoman chiefs and renegade Bulgarian nobles. The Christian population was sub jected to heavy imposts, the principal being the haratch, or capita tion-tax, paid to the imperial treasury, and the tithe on agricultural produce, which was collected by the feudal lord. Among the most cruel forms of oppression was the requisitioning of young boys between the ages of ten and twelve, who were sent to Constanti nople as recruits for the corps of janissaries. Yet the conquest once completed, the condition of the peasantry during the first three centuries of Turkish government was better than it had been under the tyrannical rule of the boyars. Military service was not exacted from the Christians, no systematic effort was made to extinguish either their religion or their language, and within certain limits they were allowed to retain their ancient local ad ministration and the jurisdiction of their clergy in regard to in heritance and family affairs. Many districts and classes enjoyed special privileges : chief of these were the merchants, miners, and the inhabitants of the "warrior villages" (voinitchki sela), who received self-government and exemption from taxation in return for military service. Some of these towns, such as Koprivstitsa in the Sredna Gora, attained a great prosperity, which declined after the establishment of the principality. So long as the Otto man power was at its height, the lot of the subject-races was tolerable. Their rights and privileges were respected, the law was enforced, commerce prospered, good roads were constructed, and the great caravans of the Ragusan merchants traversed the coun try. Down to the end of the 17th century there was only one serious attempt at revolt, as distinguished from the guerilla war fare maintained in the mountains by the haiduti, or outlaws : that occasioned by the advance of Prince Sigismund Bathory into Walachia in 1595. Both this revolt, and an equally unsuccessful rising in 1688, were arranged in conjunction with Austrian forces; but after the peace of Belgrade (1739) Austria abandoned her active Balkan policy. Her heritage was taken over by Russia, who as early as 1687 had for political reasons assumed the role of protector of the Orthodox Christians of the Balkans ; a claim officially put forward in the Treaty of Kuchuk Kainar j i (1774). As the power of the sultans declined after the unsuccessful siege of Vienna (1683) , anarchy spread through the Balkans; although Bulgaria, being nearer the capital, still suffered less from the op pressions of the feudal lords than the remoter districts. Early in the 18th century, however, the inhabitants suffered terribly from the ravages of the Turkish armies passing through the land during the wars with Austria. Towards its close their condition became even worse owing to the horrors perpetrated by the Krdzalis, or troops of disbanded soldiers and desperadoes, who, in defiance of the Turkish authorities, roamed through the coun try, supporting themselves by plunder and committing every conceivable atrocity. In 1794 Pasvanoglu, one of the chiefs of the Krdzalis, established himself as an independent sovereign at Vidin, putting to flight three large Turkish armies which were despatched against him. This adventurer (d. 1807) possessed many remarkable qualities. He adorned Vidin with handsome buildings, maintained order, levied taxes and issued a separate coinage.

The National Revival.

At the beginning of the 19th cen tury the existence of the Bulgarian race was almost unknown in Europe. Disheartened by ages of oppression, isolated from Christendom by their geographical position, and cowed by the proximity of Constantinople, the Bulgarians took no collective part in the insurrectionary movement which resulted in the liber ation of Serbia and Greece. The Russian invasions of 1810 and 1828 only added to their sufferings, and great numbers of f ugi tives took refuge in Bessarabia, annexed by Russia under the Treaty of Bucharest. But the long-dormant national spirit now began to awake under the influence of a literary revival. The precursors of the movement were Paisii, a monk of Mount Athos, who wrote a history of the Bulgarian tsars and saints (1762), and Bishop Sofronii of Vratsa. After 1824 several works written in modern Bulgarian began to appear, and in 1835, the first Bul garian school was founded at Gabrovo. Within ten years some so Bulgarian schools came into existence, and five Bulgarian printing-presses were at work. The literary movement led to a reaction against the influence and authority of the Greek clergy. The spiritual domination of the Greek patriarchate had tended more effectually than the temporal power of the Turks to the effacement of Bulgarian nationality. Af ter the conquest of the Peninsula the Greek patriarch became the representative at the Sublime Porte of the Rum-millet, the Roman nation, in which all the Christian nationalities were comprised. The independent patriarchate of Trnovo was suppressed; that of Okhrida was subsequently Hellenized. The Phanariot clergy—unscrupulous, rapacious and corrupt—monopolized the higher ecclesiastical ap pointments and filled the parishes with Greek priests, whose schools, in which Greek was exclusively taught, were the only means of instruction open to the population. Greek became the language of the upper classes in all Bulgarian towns, the Bulga rian language was written in Greek characters, and the illiterate peasants, though speaking the vernacular, called themselves Greeks. The Slavonic liturgy was suppressed and in many places the old Bulgarian manuscripts, images, testaments and missals were burned. Thus although from 1828 onward sporadic military revolts had been led by Mamarcev, Rakovski, Panayot Khitov, Haji Dimitr and Stefan Karaja, these isolated Bulgarian patriots could not hope for success until the Greek ascendancy had been removed. For forty years the pioneers of Bulgarian nationality fought for the establishment of an autonomous church. At one time they even secured from the pope the appointment of an archbishop of the Uniate Bulgarian Church, causing Russia to urge the pope to grant Bulgaria's wishes; and on Feb. 28, 187o a firman was issued establishing a Bulgarian Exarchate with ju risdiction over 15 dioceses, including Nish, Pirot and Veles. The first Exarch was elected in Feb. 1872. He and his followers were at once excommunicated by the patriarch ; but Bulgaria was now free to develop her national feeling.

The Revolt of 1876.

Following on the rising of 1875 in Bosnia and the Hercegovina, a general revolt was organized in Bulgaria in 1876. It broke out prematurely in May in Kopriv stitsa and Panaguriste, and hardly spread beyond the sanjak of Philippopolis. It was repressed with fearful barbarity by Pomaks, bashi-bazouks and recently settled Circassians and Tatars. Some 15,000 Bulgarians were massacred near Philippopolis, including 5,00o men, women and children in Batak alone, and 58 villages and five monasteries were destroyed. Isolated risings which took place on the northern side of the Balkans were crushed with similar barbarity. These atrocities were denounced by Gladstone in a celebrated pamphlet which aroused the indignation of Europe. The Great Powers remained inactive, but Serbia declared war in the following month, and her army was joined by 2,000 Bulga rian volunteers. Reforms proposed by a conference of the Powers held at Constantinople at the end of the year, were disregarded by the Porte, and in April Russia declared war (see Russo TURKISH WARS, and PLEVNA). In the campaign which followed the Bulgarian volunteer contingent in the Russian Army accom panied Gourko's advance over the Balkans, behaved with great bravery at Stara Zagora, where it lost heavily, and rendered valu able services in the defence of Shipka.Independent Bulgaria. Treaties of San Stefano and Ber lin.—Af ter advancing to Chatalja, Russia dictated the Treaty of San Stefano (Mar. 3, 1878) which realized almost all Bulgarian ambitions. An autonomous principality was created, the western frontier of which ran down from the Timok river to embrace Pirot, Vranje, Skoplie, Debar, Okhrida and Kastoria. Leaving Salonika and Chalcidice to Turkey, the frontier left the Aegean south-east of Xanthe and ran along the Rhodopes, passed north of Adrianople, curved down to include Lule-Burgas, and reached the Black sea north of Midia. The Dobruja was reserved as com pensation to Rumania for Russia's annexation of Bessarabia. The area included in the new Bulgaria constituted three-fifths of the Balkan peninsula, with a population of 4,000,000 inhabitants. The Powers, however, fearing that this State would become prac tically a Russian dependency, intervened. The Treaty of Berlin, (q.v.), of July 13, 1878, reduced the principality of Bulgaria, (which was to be independent, but under the sovereignty of the Porte), to the territory between the Danube (excluding the Dobruja) and the rest of the Balkans, with Samokov and Kius tendil. Vranje, Pirot and Nish were given to Serbia, Turkey re taining nearly all' Macedonia. An autonomous province of East ern Rumelia, subject to the sultan but with a Christian governor general, a diet and a militia, was created between the Balkans and the Rhodopes. A European commission was to draft a constitu tion for Rumelia; for Bulgaria, an assembly of notables was to meet at Trnovo within nine months, draw up an organic law and elect a prince; their choice was to be confirmed by the Porte with the assent of the Powers. The country was meanwhile occupied by Russian troops and administered by Russian officials.

The Constitution of Trnovo and the Election of Prince Alexander.—The Constituent Assembly, which met at Trnovo on Feb. 22, 1878, was overwhelmingly democratic in character. The majority of its members were peasants, and the Liberal party, under Tsankov, Karavelov and Slaveikov, easily predomi nated over the Conservatives. The constitution elaborated at this assembly (see section CONSTITUTION) was among the most demo cratic in Europe.

On Aug. 29, 1879 the first regular Bulgarian Assembly elected to the Bulgarian throne Prince Alexander of Battenberg, a mem ber of the grand-ducal house of Hesse and nephew of the tsar Alexander II. of Russia. Prince Alexander arrived in Bulgaria and took the oath to the Constitution on June 26 amid general re joicings; but from the first his position was difficult. Elected as Russia's candidate, and autocratic by nature and training, the young prince considered himself less a Bulgarian ruler than an agent for the foreign and domestic policy of his protector. Little else was, indeed, expected of him by the courts of Europe, but on both these scores he came into early conflict with the Bulgarian Liberals, now led by Stambulov, who commanded the bulk of Bul garian public opinion and were strongly averse from any un national policy, or any infringement of the democratic constitu tion. The prince first formed a Conservative ministry to take the place of the outgoing Russian officials, but was forced by the popular agitation to form a Liberal Government under Tsan kov. As the Liberals, once in power, initiated a violent anti-foreign and anti-Russian agitation, the prince dismissed them, formed a new Conservative Government under the Russian general Ernroth, and charged him with arranging new elections to the Grand Sob ranje. The general obtained a subservient sobranje which agreed ( July 13, 1881) to suspend the constitution and invest the prince with absolute powers for seven years. A period of dictatorship fol lowed, under the Conservatives and the Russian generals Sobolev and Kaulbars, who were despatched from Russia to enhance the authority of the prince. His own adherents, however, disagreed among themselves over the question of railway concessions. The prince, whose relations with Russia had been less cordial since the death of Alexander II. in 1881, quarrelled with Sobolev, and began to favour Bulgarian aspirations. On Sept. Iq, 1883 he restored the constitution by proclamation, and formed a coalition Government of Conservatives and moderate Liberals, which was succeeded on July g, 1884 by a government of the Left-wing Liberals under Karavelov.

Union with Eastern Rumelia and War with Serbia.— In East Rumelia, as in Bulgaria, political life had brought forth a Conservative, or "Unionist," and a Liberal party. The differ ences between them were rather personal than of principle, for each was equally eager to promote the union with Bulgaria, but the Unionists, who were Russophil, had declared, in compliance with Russia's wishes, that the time was not yet ripe for the union. The Liberals, who were in opposition, seized the opportunity and on Sept. 18, 1885, having assured themselves beforehand of Prince Alexander's consent, they seized the governor-general, Krastovic Pasha, and proclaimed the union. The prince arrived in Philippopolis a few days later, took over the government, and mobilized all available troops on the Turkish frontier to resist a possible attack. Turkey, however, beyond massing her troops on the frontier, made no move, but awaited developments in the in ternational situation. The Western Powers showed Bulgaria sym pathy, and Germany preserved a neutral attitude, but Russia, incensed by such independence of action, recalled her officers from the Bulgarian Army, and summoned conferences in Con stantinople in September and October, where she urged that the union be cancelled and the sultan's authority restored in East Rumelia. This was opposed by Great Britain; and meanwhile King Milan of Serbia, declaring that the balance of power in the Balkans was endangered, suddenly declared war (Nov. 14, 1885) The Serbs advanced as far as Slivnitsa; but here they were met and brilliantly defeated by the untrained Bulgarian Army (Nov. DO which pursued them over the frontier, took Pirot (Nov. 27), and was only stopped by the intervention of Austria (see SERBOBULGARIAN WAR). Peace and the status quo were restored by the Treaty of Bucharest (March 3, 1886), and by the Convention of Top-Khane (April 5) . Prince Alexander was appointed governor general of East Rumelia, and the Rumelian administrative and military forces united with those of Bulgaria.

The Abdication of Prince Alexander and the Regency. —Discontent with these events impelled Russia to set afoot a conspiracy among the Russophils in Bulgaria and certain dis contented officers, who on Aug. 21, 1886 seized the prince in his palace, forced him to sign his abdication, and transported him out of the country. The country in general disapproved the plot ; Stambulov, the president of the assembly, and Colonel Nutkurov, commandant of the troops at Philippopolis, initiated a counter revolution, overthrew the conspirators and recalled the prince. The tsar, however, whom he had informed of his return, answered: "I cannot approve your return to Bulgaria." As no European Power would support him in face of Russia's Alexander abdicated on Sept. 7, appointing as regents Stambulov, Karavelov and Mutkurov. The regency was successful, in difficult circum stances, in preserving order and securing the goodwill of Turkey. The election of a new prince was a more difficult task. Russia sent Gen. Kaulbars to Bulgaria to arrange for the election of the prince of Mingrelia; but finding fresh causes of discontent, broke off relations on Nov. 17. The Bulgarian delegates who toured the courts of Europe found the difficulty of selecting a prince who should be agreeable to Russia and to the rest of Europe alike, al most insurmountable. At last their offer was accepted by Prince Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (q.v.).

Prince Ferdinand.

The new prince was elected by the Grand Sobranje on July 7, 1887, and took over the Government on July 14. His position was difficult, as Russia denounced him as a usurper and brought pressure on the Porte to declare his presence in Bulgaria illegal. Stambulov, who became minister president on Aug. 3, had to rule almost as a dictator in face of a raid led by the Russian captain Nabokov, a refusal by the bishops of the Holy Synod to pay homage to the prince, and a military con spiracy under Major Panitsa (1890). Fortunately Stambulov's foreign policy was very successful. The Powers withheld recog nition ; but Ferdinand was received personally in Vienna, London and Rome ; and relations with Turkey became really cordial, the Porte granting the Bulgarian schools and Church valuable con cessions in 1890, 1892 and 1894. While, however, Stambulov sought the friendship of the Porte, Ferdinand was anxious to re cover the favour of Russia, and thus secure his own recognition. Relations between the two grew ever more strained, until Stam bulov resigned in 1894. Under his successor, Dr. Stoilov, Ferdi nand inaugurated a Russophil policy, which was facilitated by the death of the Tsar Alexander III. in Nov. 1894. The banished Russophils and other victims of Stambulov's autocratic regime were amnestied; some of these murdered the great minister in the streets of Sofia on July 14, 1895. In the spring of 1893 Ferdinand had married Princess Marie Louise of Bourbon-Parma, Stambulov had persuaded the Grand Sobranje to alter the con stitution and to allow the issue of the marriage to be brought up in the Roman Catholic faith. Now, however, he had his eldest son, Prince Boris, baptized into the Orthodox faith (Feb. 14, 1896), a step which, although it incurred the grave displeasure of Austria-Hungary, sealed the reconciliation with Russia. On March 14, the Powers having signified their assent, Ferdinand was nomi nated by the sultan prince of Bulgaria and governor-general of Eastern Rumelia. Russian influence again became predominant in Bulgaria. It was no longer conspicuous in her internal affairs, but a secret military convention was concluded in Dec. 1902.The Macedonian Question and the Declaration of In dependence.—The question which was now to dwarf all others in importance, and to sway all Bulgarian policy, was that of Macedonia. The narrow limits drawn by the Treaty of Berlin had left Bulgarians under foreign rule in Rumania, Serbia and Turkey. If the hope of recovering portions of the Dobruja and Western Serbia had prevented Bulgaria from initiating cordial relations with those two countries, she had recognized the im possibility of an aggressive war. With Turkey, however, matters were different. Macedonia constituted the largest Bulgaria ir ridenta ; here the sense of Bulgarian nationality was especially strong and genuine ; here, too, there was a fair possibility that the present masters would soon leave the field, and territorial acquisition prove possible. The Macedonian revolt of 1903 (see MACEDONIA) brought Bulgaria to the verge of war with Turkey; and despite a convention of April 8, 1904, she was obliged to keep up an army with a view to possible war, which, together with the maintenance of many destitute refugees from Macedonia, proved a heavy drain on her finances. Nor did the question end here. Other countries laid claim to Macedonia. Serbs, Greeks, Albanians, Vlachs, as well as Bulgars, carried on their rival propagandas by force of arms. Outrages committed by Greek bands in 1906 led to reprisals on the Greek population in Bulgaria, while with Serbia the situation was even more strained, especially since the return of the Karageorgevic dynasty in 1903, the conse quent increase in Serb propaganda in Macedonia and the increas ing favour enjoyed by Serbia in Russia. It was partly, no doubt, the desire to set his country on an equality with Serbia, as well as the growing impatience of prince and people alike at the nominal vassalage to Turkey (even though the tribute imposed in 1878 was never paid) that decided Prince Ferdinand to proclaim Bulgarian independence. On visiting Vienna in Feb. 1908, Prince Ferdinand was well received; Bulgaria's aspirations towards the Dobruja and Nish made the conclusion of an alliance between her and Austria-Hungary impossible ; but they were now in sympathy. After the Young Turk revolution of July 1908 an understanding was reached between Ferdinand and the Emperor Francis Joseph. Further pretexts were supplied by a diplomatic incident in Constantinople, and a strike in those sections of the Eastern Rumelian railways which were owned by Turkey but leased to the Oriental Railways. On Oct. 5, 1908, the day after the Austrian annexation of Bosnia and the Hercegovina, Ferdinand proclaimed Bulgaria (including Eastern Rumelia) an independent kingdom. (J. D. B.; C. A. M.) The Balkan Alliance and the First Balkan War.—The protests of Serbia against this action were stilled by Russia, who feared that Bulgaria might be driven definitively into the arms of Austria-Hungary. Bulgarian policy swung back into its old groove. Turkey had claimed an indemnity of £4,800,000 for the Decla ration of Independence. Bulgaria had agreed to pay £1,520,000. In Feb. 1909 Russia undertook to advance the difference. A preliminary Russo-Turkish protocol was signed on March 16, and in April, after the final agreement had been signed, the independ ence of Bulgaria was recognized by the Powers.

In March 1911 the Malinov cabinet fell, and Guesov, head of the Nationalist party, became minister president. Negotiations for a Balkan alliance against Turkey commenced. The first, be tween Bulgaria and Greece, were conducted through J. D. Bour chier, Balkan correspondent of the London Times. A secret treaty of defensive alliance was signed between Bulgaria and Greece on May 29, 1912. The Serbo-Bulgar treaty was signed in Sofia on March 13, and supplemented by the secret military conventions of Varna, May 12 and July 12. Bulgaria had desired autonomy for Macedonia; Serbia, its division into uncontested Bulgar and Serb zones, and a third zone on which the tsar of Russia was to arbitrate. Ultimately Serbia recognized "the right of Bulgaria to the territory east of the Rhodope mountains and the river Struma"; while Bulgaria recognized "a similar right of Serbia to the territory north and west of the Sar mountains"; if autonomy for the rest of Macedonia proved impossible, an agreed line from Golem Mountain to Okhrida was to be accepted, subject to the tsar's approval. Hartwig, the Russian minister at Belgrade, had kept his government informed throughout. Early action was nec essary in view of the approaching end of the Italo-Turkish War and the unrest in Macedonia. The Great Powers endeavoured to prevent war by the tardy offer of a guarantee for the autonomy of Macedonia. The Balkan Allies mobilized on Sept. 30. On Oct. 8, Montenegro, with which country no formal agreement had been made, declared war on Turkey. On Oct. 13 the Balkan Al lies sent an ultimatum to the Porte; on Oct. 18 Greece declared war on Turkey.

The successes of the Balkan Allies were swift, although the casualties of Bulgaria, especially, were heavy. On Dec. 3 an armistice was signed between Turkey, Bulgaria and Serbia. A conference met in London to decide terms of peace, but negoti ations broke down over the possession of Adrianople. On Feb. 3, 1913, hostilities reopened. Again the allies were everywhere suc cessful, and of ter the surrender of Adrianople to the Bulgars and Serbs (March 26) the Turks sought the mediation of the Powers, and a second armistice was concluded between Bulgaria and Turkey on April 16. On May 30 1913 the delegates to the second London Conference were induced to sign a treaty, the terms of which had been drafted by the Powers. Turkey sur rendered to the allies all her possessions in Europe up to a line drawn from Enos on the Aegean to Midia on the Black sea. Albania was granted independence. (See BALKAN WARS.) The Second Balkan War.—Difficulties immediately arose as to the interpretation of the treaty. The Serbs claimed that, after the unforeseen success of the campaigns and the modification by the Powers of the arrangements on the Adriatic coast, a revision of the treaty was necessary, while the Bulgars held out for the letter of the territorial agreement. The secret annexes (March 13, 1912) stated that "all territorial gains acquired by combined action ... shall constitute the common property (condominium) of the two allies" until final settlement. The Serbs and Greeks, as a result of their victories, held much territory in Macedonia that had originally been assigned to Bulgaria, and they seemed to be preparing for a permanent occupation. Early in 1913 Bul garia began to suspect that her allies were combining against her, and the military party, with King Ferdinand at their head, pre pared for action.

On June i Guegov and Pasic met in the hope of averting war; on the same day a treaty between Serbia and Greece was signed at Salonika. Guesov, finding no support from King Ferdinand in his efforts for peace, resigned; he was succeeded by Danev. On June 29 the Bulgarian 4th Army, acting on orders signed by Gen. Savoy, made a treacherous attack on their Serbian and Greek allies. It must, however, be remembered that the attack was not unexpected, and that it probably only just forestalled a decla ration of war by Serbia and Greece. Guesov states in his memoirs that the reports of the Minis terial council contain no minute ordering the attack. A judicial inquiry into the case was opened in Sofia, but never concluded.

Savoy asserted that Ferdinand as commander-in-chief gave the order to attack.

The Second Balkan War brought calamity on both Bul garia and Macedonia. By the Treaty of Bucharest (Aug. io, 1913) Rumania acquired the rich lands of the Southern Dobruja, which had belonged to Bulgaria since 1878; Serbia and Greece divided Macedonia between them ; Bulgaria was accorded the mountainous region of the Pirin and Dospat down to the Aegean, with the two indifferent ports of Dedeagatch and Port Lagos.

Rapprochement with the Central Powers.

The Rado slavov Government which took office in July 1913, abandoned the Russophil policy which had given Macedonia to Serbia. When France, Britain and Russia refused to grant a loan to meet ob ligations and for constructive work, they turned to the Central Powers, and in July 1914 concluded a loan of 500,000,000 leva with the Disconto-Gesellschaft of Berlin, the group obtaining con trol of the Bulgarian State coal mines, the port of Lagos, and the projected railway to it. Negotiations for a treaty had been going on simultaneously, and in August were approaching com pletion (see EUROPE) ; and thus, when the World War broke out, although most Bulgars wished to preserve neutrality, the pro German sympathies of the king, who also believed Germany in vincible, were reinforced by a widespread feeling that the Central Powers, and they alone, might yet gain Macedonia for Bulgaria. The efforts made by the Entente through the summer of 1915 to win over Bulgaria were frustrated by the refusals of Serbia and Greece to cede territory. On Sept. 6 Bulgaria signed a military convention and treaty with the Central Powers at Pless (Pszczy na), and Turkey made the concessions demanded by Bulgaria. On Sept. 15 the Entente promised Bulgaria part of Macedonia unconditionally, if she would declare war on Turkey. The Op position protested vehemently against the king's policy, Stam bolisky being, in consequence, condemned to imprisonment for life for lese-majeste, but mobilization was decreed on Sept. 22, and Bulgaria declared war on Serbia on Oct. 12. Great Britain, France and Italy declared war on Bulgaria on Oct. 15, 16 and 17 respectively.The World War, 1915-18, and the Treaty of Neuilly. The initial successes of the Bulgarian troops in Serbia, and later in the Dobruja, gave some popularity to the war; but the Opposi tion continued to urge retirement from the War, especially when her national objectives, Macedonia and the Dobruja were attained. Southern Dobruja passed to her, with immediate occupation, un der the Treaty of Bucharest, May 7, 1918; but shortage of food and munitions, exhaustion, and the hopes raised by President Wil son's pronouncement of the Fourteen Points, intensified the desire for a separate peace. Malinov replaced Radoslavov in office on June 18, and when the Bulgarian line was broken and the country invaded (Sept. 15-27), he asked for an armistice, which was signed unconditionally on Sept. 29. Stambolisky, who had been released on Sept. 25 and sent to the front to calm the troops, proclaimed a republic and advanced on Sofia; order was restored by loyal troops with German assistance, after some fighting. On Oct. 3 King Ferdinand abdicated in favour of his son Boris and left the country. Under the Treaty of Neuilly (q.v.) Bulgaria was disarmed, condemned to a heavy indemnity, and lost the Southern Dobruja to Rumania, Caribrod and Strumica to Yugoslavia, her recent gains in Macedonia to Greece, and her Aegean coastline to the Allies and Associated Powers, who as signed it to Greece at the Conference of San Remo (April 1920, q.v.).

The Agrarian Government, 1920-23.

Post war revolution ary feeling in Bulgaria took the form of a reaction against her war policy. Stambolisky, its most courageous opponent, was the hero of the hour. The elections of March 28, 1920 gave the Agrarians an absolute majority, and Stambolisky, as premier of an Agrarian cabinet, opened a campaign against the bourgeoisie which in its methods closely resembled that of the Russian Bol sheviks, with whom he later opened up direct communications; he was also the author of a plan for a "Green international" of peasants. He used the Communists of Bulgaria as allies against the bourgeoisie, but denounced and persecuted them as enemies of property. His valuable measures, which were not repealed after his fall, were an agrarian law whereby Crown and Church lands and property over a certain size (3o hectares for peasant pro prietors, ten for married, four for single urban proprietors who did not themselves cultivate the soil) were expropriated in favour of landless peasants ; and the institution of a year's obligatory State service.Stambolisky's foreign policy was sensible and conciliatory. He attempted to live on peaceful terms with his neighbours and to fulfil treaty obligations. Despite grave economic difficulties, Bulgaria commenced payment of the reparations, the total of which was finally reduced from £9o,000,000 to L22,000,000, pay able over 6o years. Despite this, Bulgaria failed at the two con ferences of Lausanne to secure an adequate fulfilment of clause 48 of the Treaty of Neuilly, which guaranteed her an issue to the Aegean (see THRACE), and her relations with her neighbours were left in a state of tension by the question of the Bulgarian minorities in Thrace, Dobruja and Macedonia.

The Refugee Question.

The Treaties of Bucharest (1913) and Neuilly had left large numbers of Bulgars under foreign rule, which was in most cases extremely harsh and unjust. While those who remained in their homes complained of oppression, large numbers took refuge in Bulgaria, while others were brought in under the exchange of population scheme with Greece. Since 1918 alone 260,000 refugees had entered Bulgaria, mostly from Macedonia and Thrace ; and most of these were landless, desti tute, and resentful, while the Bulgarian State, with its shattered finances, could do little to relieve their miseries. A large pro portion of the population of Bulgaria, refugee or otherwise, was of Macedonian origin, and the powerful and ruthless Internal Organization of the Macedonians, under their capable and ter rible leader, Todor Alexandrov (q.v.), gained general sympathy in its fight for Macedonian autonomy, and thus formed an under ground factor of the first importance in Bulgarian politics. While the Bulgarian delegates to the League of Nations (which Bulgaria joined on Dec. 16, 1920) voiced at every opportunity the griev ances of the Bulgarian minorities in Macedonia, Thrace and the Dobruja, the refugee organizations, particularly the Macedonians, raided the territory of Bulgaria's neighbours from their fastnesses in the Bulgarian mountains, and thus helped to perpetuate a state of discord between Bulgaria and her neighbours. The Bulgarian Government was not the least of the sufferers from the situation; and an agreement concluded by Stambolisky with the Yugoslav Government at Nish (March 1923) was believed to contain a clause directed against the Macedonian Committee. Upon this the Macedonians combined with the Bulgarian Nationalists and those of the officers and bourgeoisie who had suffered most from Stambolisky's arbitrary rule. A coup-d'etat in the night of June 8/9, 1923, overthrew the Agrarian Government. Stambolisky was killed, most of his ministers imprisoned, and his Orange Guards dispersed.The Tsankov Government, 1923-25.—Professor Tsankov now took office at the head of a government subsequently strength ened by the fusion of all political parties, except the Liberals, Communists and Agrarians, into the single "Democratic Entente." For some time Bulgaria was on the verge of civil war. The Agra rian refugees migrated in large numbers to Yugoslavia, where the Government gave them shelter, and allied themselves with the Communists, who with support from Moscow, attempted to bring about a revolution. Tsankov repressed these movements with great severity. In September several thousand persons were killed, and others imprisoned for long periods without trial. Mean while the Comitad ji warfare on the frontier continued. Relations with Greece, especially, became particularly difficult on account of the severe reprisals taken by that country for an attempted rising in the Maritsa valley in 1923, and an incident at Tarlis on July 26/27, 1924, where a Greek post arrested 7o Bulgars and murdered several of their prisoners. A protocol signed at Geneva between Greece and Bulgaria, on Sept. 29, 1924, which had promised a settlement, was repudiated by Greece at the instance of Yugoslavia. Meanwhile acute dissensions broke out within the Macedonian organization itself, one group of which wanted autonomy for Macedonia, the other a federative scheme. There was a further disagreement as to how far the help of Moscow ought to be accepted. On Aug. 31, 1924 Alexandrov was murdered, and the subsequent reprisals deprived the organization of most of its coherence and moral justification. The Agraro-Communist agitation, too, continued unabated. There were some 200 assas sinations in 1924; on April 14, 1925 an attempt was made on the life of King Boris, and General Gheorghiev was killed the next day. At his funeral, which was held on April 16 in the cathedral of Sveta Nedelia, Sofia, a bomb was exploded killing 123 persons and wounding 323. The Government proclaimed martial law. Five persons were later hanged publicly for the crime, but a large num ber were either shot summarily or imprisoned. To maintain order, the Government obtained the permission of the Conference of Ambassadors for a temporary increase in its armed forces of 10,000 men; and in fact, its extreme en ergy prevented any general rising. The Tsankov Government also successfully survived a fresh frontier incident with Greece, which occurred on Oct. 19, when Greek troops occupied 7o square miles of Bulgarian territory near Petritch. The matter was settled by the League of Na tions (q.v.) on appeal from Bulgaria. The repressive measures which Tsankov had felt obliged to take had, however, been more fitted for emergencies than for ordi nary times, and as the Agraro-Communist agitation seemed much sobered by the dreadful events of the spring of 1925, Tsankov resigned on Jan. 2, 1926 in favour of a more conciliatory government under Liapchev, a leader of the Democratic party. On Feb. 4 the Liapchev Govern ment promulgated an amnesty for political offenders, which affected 6,325 persons.

The Liapchev Government and the Refugee Loan.—The effects of this change were most beneficial. The Agra rians were allowed to reconstitute their party in Bulgaria, and the 2,000 or so emigres who remained in Yugoslavia soon lost credit. The Social Democrats were less fortunate, but even here hostility gradually grew less as Moscow ceased to finance the extreme Corn munists so liberally.

On June 11, 1926, the Council of the League of Nations de cided that the state of Bulgaria warranted the grant of a loan, for which application had first been made 18 months previously, for the settlement of the destitute Bulgarian refugees. The question was of supreme importance for Bulgaria, both financially and politically, for it was from among these refugees, with whom the whole population sympathized, that the comitadjis were re cruited, whose incessant frontier raids so troubled Bulgaria's rela tions with her neighbours. Following the decision of the League. the Bank of England on Aug. 26 advanced £400,000 for immediate work, which was at once set on foot. An arrangement with the bond-holders of Bulgaria's pre-War debt was signed on Dec. and the loan, for L2,400,000 nominal in England and $4,500,000 in the United States of America, was floated very successfully on Dec. 26. Bulgaria's neighbours had shown an unjustifiable apprehension regarding the application of the Loan funds, and had made fresh outbursts of comitadji activity in the summer of 1926 the occasion of a joint note to the Bulgarian Government demanding the dissolution of the revolutionary organizations (Aug. 27). This was, indeed, more easy to demand than to ful fil; but there seemed little doubt that Liapchev's Government was sincerely anxious to restrain the Macedonian and other com mittees. Bulgaria had been politically almost isolated for more than a decade; a treaty of friendship signed with Turkey on Oct. 18, 2925 was no compensation for continual tension with Yugo slavia, Greece and Rumania. Factors began however, to tend in favour of a rapprochement. The apprehensions of Yugoslavia were aroused by the conclusion in 1926 of the Treaty of Tirana between Italy and Albania; although attempts to improve rela tions with Bulgaria were frustrated by new Macedonian outrages. In May 1934 the "Zveno" group seized power in Bulgaria, sus pended the constitution, and dispersed with ease the terrible Mace donian Organization. The revival of German interest in the Bal kans after 1933, coupled with fresh Italian pressure, produced a change of attitude among Bulgaria's neighbours; and in July 1938 a non-aggression pact was signed between Bulgaria and the Balkan Entente, by which the armament clauses of the Treaty of Neuilly were abrogated. The Zveno group was replaced in 1935 by a re publican sentiment, but the authoritarian form of rule continued with Prof. Tosheff and later M. G. Kiosseivanoff as premier.

C. J. Jirecek, Geschichte der Bulgaren (Prague, 1876) ; Acta Bulgariae ecclesiastica, published by the South Slavonic Academy (Agram, 1887) ; A. G. Drander, Evenements politi ques en Bulgarie (1896) ; Le P. Guerin Songeon, Histoire de la Bul garie (1913) ; I. Guelov, The Balkan League (1915) ; R. W. Seton Watson, Rise of Nationality in the Balkans (1917) ; Geschichte der Bulgaren (Bulgarische Bibliothek) vol. ii. Prof. Stanev (Leipzig, 1917) and vol. i., Prof. Slatarski (Leipzig, 1918) ; N. Buxton and C. L. Leese, Balkan Problems and European Peace (1919) ; L. Lamouche, La question Macedonienne et la Paix; Le Traite de Paix avec la Bulgarie (1919) ; M. Bogicevic, Causes of the War, with Special Reference to Serbia and Russia (1920) ; Diplomaticheski Dokumenti po Nameshchatana Bulgaria v evropei S. Rava voina, vol. i., 1913-15 (192o) ; A. V. Nekludov, Diplomatic Reminiscences, 191I-17 (192o) ; Bulgaria, "Nations of To-day" Series (1921) ; P. Gentizon, Le drame bulgare (1924) ; E. C. Corti, Alexander von Battenberg 2nd ed. (1928) ; Reports on the Bulgarian Refugee Settlement (League of Nations, Geneva, 1926 ff.). Travels and Economics: C. J. Jirecek, Das Fiirstenthum Bulgarien (Prague, 1891) ; Cesty po Bulharsku (Travels in Bulgaria) (Prague, 1888) ; Prince Francis Joseph of Battenberg, Die Volkswirtschaftliche Entwicklung Bulgariens (Leip zig, 1891) ; F. Kanitz, Donau—Bulgarien and der Balkan (Leipzig, 1882) ; A. Strausz, Die Bulgaren (Leipzig, 1898) ; A. Tuma, Die ostliche Balkanhalbinsel (1886) ; La Bulgarie contemporaine (issued by the Bulgarian Ministry of Commerce and Agriculture) (19o0 ; Publications Plumon, La Bulgarie, la vie technique et industrielle (1921) . Literature: L. A. H. Dozon, Chansons populaires bulgares inedites (with French trans.) (1875) ; A. Strausz, Bulgarische Volks dichtungen (trans. with a preface and notes) (Vienna and Leipzig, 1895) ; Lydia Shishmanov, Legendes religieuses bulgares (1896) ; Pypin and Spasovich, History of the Slavonic Literature (in Russian, 1879) (French trans., 1881) ; Vazov and Velitchkov, Bulgarian Chrestomathy (Philippopolis, 1884) ; Teodorov, Blgarska Literatura (Philippopolis, 1896) ; Collections of folk-songs, proverbs, etc., by the brothers Miladinov (Agram, 1861), Bersonov (Moscow, Kachanovskiy (Petersburg, 1882), Shapkarev (Philippopolis, 1885), Iliev (Sofia, 1889), P. Slaveikov (Sofia, 1899). (E. F. B. G.)