Hepaticae

HEPATICAE The three groups into which liverworts are botanically divided show among their several members lines of progression in three different directions from a basal, simple type more or less common to them all. Stated broadly, evolution in liverworts has progressed from a common form along three distinct lines. From such a simple type, for instance, the Marchantiales have moved along the line of increasing complexity in texture of the thallus, the Jungermanniales have retained the simplicity of texture but show an increasing tendency to discard the thalloid and assume a leafy shoot habit, whilst the Anthocertales have retained both the simple texture and habit of the thallus but developed a peculiar sporo gonium. These tendencies require fuller discussion.

Marchantiales: Structure.

Of the Marchantiales, the genus Riccia, with a world-wide distribution and including many species, affords the simplest organization of the group. Riccia consists of a flat, dichotomously-branched thallus growing appressed to the ground, attached thereto by rhizoids. The growing apex lies at the base of a heart-shaped cleft at the end of the thallus, the two lateral lobes being produced by the enlargement of cells cut off from the apical cell or cells. This thallus is thickest in its middle line but thins out towards the edges; its upper half con sists of vertical columns of green chlorophyll-containing cells, its lower half of cells comparatively free from chlorophyll irregularly crowded together and acting as storage cells for the food manu factured by the upper assimilating half. Provision for aeration has here its lowest expression, being represented merely by small spaces between the vertical rows of cells in the upper half of the thallus. On the lower surface one finds the hair-like structures, rhizoids, already mentioned, and of these two types may be recog nized, smooth and tuberculate. The latter, their name implies, possess many small pegs of cellulose projecting into the cavity from the wall of the cell. In addition to rhizoids on the under side there are present small scales or plates of cells which we call ventral scales or amphigastria. Riccia is peculiar in that the ventral scales arise singly from the growing point and are later torn into more by lateral expansion of the thallus, whereas in all other Marchantiales forms, they arise in pairs—a fact of possibly great theoretical significance. Corsinia gives us a step in advance in texture of the thallus. Here the upper part of the thallus shows well-developed air chambers bounded on all sides by plates of cells, below by the storage tissue and roofed in by an epidermal layer of cells; each chamber is open to the air by a simple pore. Reboulia shows much the same structure, but in Fegatella we meet a further advance in complexity. The air chambers here are very evident as in Corsinia, they open by a simple pore in just the same way but the space within the chamber is crowded with small columns of cells projecting into the cavity from its floor. These columns of cells are bathed by air and are packed with chlorophyll-bearing plastids. A still fur ther advance is shown by Preissia and Marchantia. Here the thallus, air chambers and assimilating filaments are the same as in Fegatella, but the pores are very different. The pore in the epidermal roof of the air chamber takes the form of a small barrel with both ends open; the cells forming the sides, on occa sions of drought, close the lower end of the barrel, which projects into the cavity (fig. 3) .

Marchantiales: Gametophyte.

Alongside this progression in thallus complexity go other striking features. In Riccia the antheridia and archegonia are scattered irregularly over the upper surface of the thallus, sunk in the vertical columns of assimilat ing tissue, or if there is any sign of grouping of these reproductive organs it is very indefinite. Corsinia has separate male and female plants, and the male are very scarce and difficult to find even in a fruiting culture. The archegonia occur in groups and they come to lie in a saucer-shaped depression in the upper surface of the thallus. Furthermore, after an egg-cell is fertilized a small region of thallus tissue behind the archegonium grows rapidly and results in an irregular hood overhanging the sporogonium. This hood foreshadows a dominant feature of higher forms. In Plagiochasma we see a further advance. Both antheridia and archegonia are usually found in the same plant, the antheridia commonly formed first and appearing grouped together on small button-shaped masses of tissue along the dorsal surface of the thallus. The archegonia are also produced in compact groups, but here the portion of thallus bearing them grows up quickly and results in a stalked structure externally much like a miniature mushroom. This stalked mass of thallus tissue lifts up the archegonia which become displaced to the under edge of the cap and forms the structure we call an archegoniophore or more usually a carpo cephalum. Here in Plagiochasma it arises on the dorsal surface behind the apex and is simply a dorsal outgrowth. In Grimaldia we have still further advance. A dorsal carpocephalum is formed as in Plagiochasma, but its formation stops the growth of the thallus apex and further growth is by a ventral branch. From this stage it is but a step to Reboulia where a carpocephalum is formed very much like Plagiochasma, but we find that there is a groove running up the stalk and branching in the cap, and that these grooves are packed with rhizoids. In short the apical cell of the thallus has been utilized in the formation of the carpo cephalum which is now a branch of the thallus and no longer a dorsal outgrowth. Preissia and Marchantia, especially the latter, reach the extreme development in this respect. Here the an theridia are borne on stalked apical structures, antheridiophores, the antheridia being embedded in the upper surface of the cap. Both antheridiophores and carpocephala have grooves packed with rhizoids; they are branch structures and further growth of the thallus must be by ventral branch (fig. 3).

Marchantiales: Sporophyte.

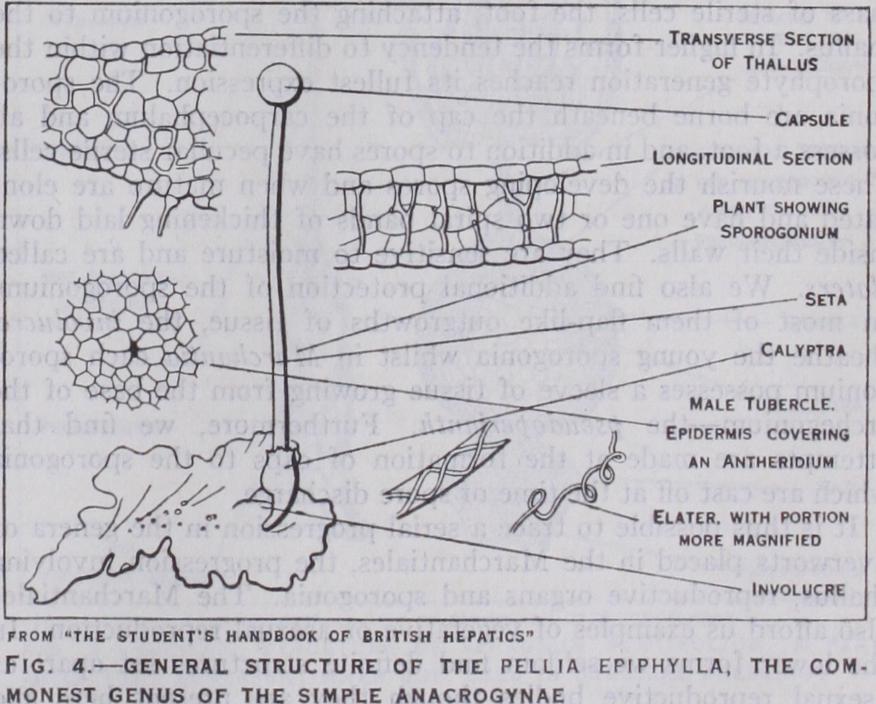

The sporophyte generation in creases in complexity along the same line. In Riccia the sporo phyte is again in its simplest form, consisting of a spherical body which is just a single wall of sterile cells enclosing nothing but spores. This simple sporogonium is sunk in the tissue of the thallus and is surrounded by a double layer of cells, the calyptra, derived from the venter of the archegonium. Spore discharge is afforded by decay of gametophyte tissue and wall of sporogonium. In Corsinia the sporogonium is not sunk in the thallus tissue, and has, in addition to the Riccia-like structure of its sporo gonium, sterile cells intermixed with the spores and a definite mass of sterile cells, the foot, attaching the sporogonium to the thallus. In higher forms the tendency to differentiation within the sporophyte generation reaches its fullest expression. The sporo gonia are borne beneath the cap of the carpocephalum and all possess a foot, and in addition to spores have peculiar sterile cells. These nourish the developing spores and when mature are elon gated and have one or two spiral bands of thickening laid down inside their walls. They are sensitive to moisture and are called elaters. We also find additional protection of the sporogonium. In most of them flap-like outgrowths of tissue, the involucre, sheathe the young sporogonia whilst in Marchantia each sporo gonium possesses a sleeve of tissue growing from the base of the archegonium—the pseudoperianth. Furthermore, we find that attempts are made at the formation of caps to the sporogonia which are cast off at the time of spore discharge.It is thus possible to trace a serial progression in the genera of liverworts placed in the Marchantiales, the progression involving thallus, reproductive organs and sporogonia. The Marchantiales also afford us examples of vegetative or asexual reproduction. In the lower forms we seldom find definite structures set apart as asexual reproductive bodies though they are present here and there—generally any branch of the thallus may become detached by decay of older parts and thus lead to increase in number of plants. Marchantia, however, has definite buds, or gemmae, which are multicellular bodies, in shape much like the base of a fiddle, borne in large numbers in circular cups on the upper face of the thallus (fig. 3) . Each gemma can reproduce a new plant. Lun nularia has similar gemmae-cups, though these are semilunar in shape.

The Jungermanniales do not show such a neat progression in structure as the Marchantiales. They show progression from the simple thalloid type towards the leafy habit and fall easily into two groups, the Anacrogynae and the Acrogynae.

Anacrogynae.

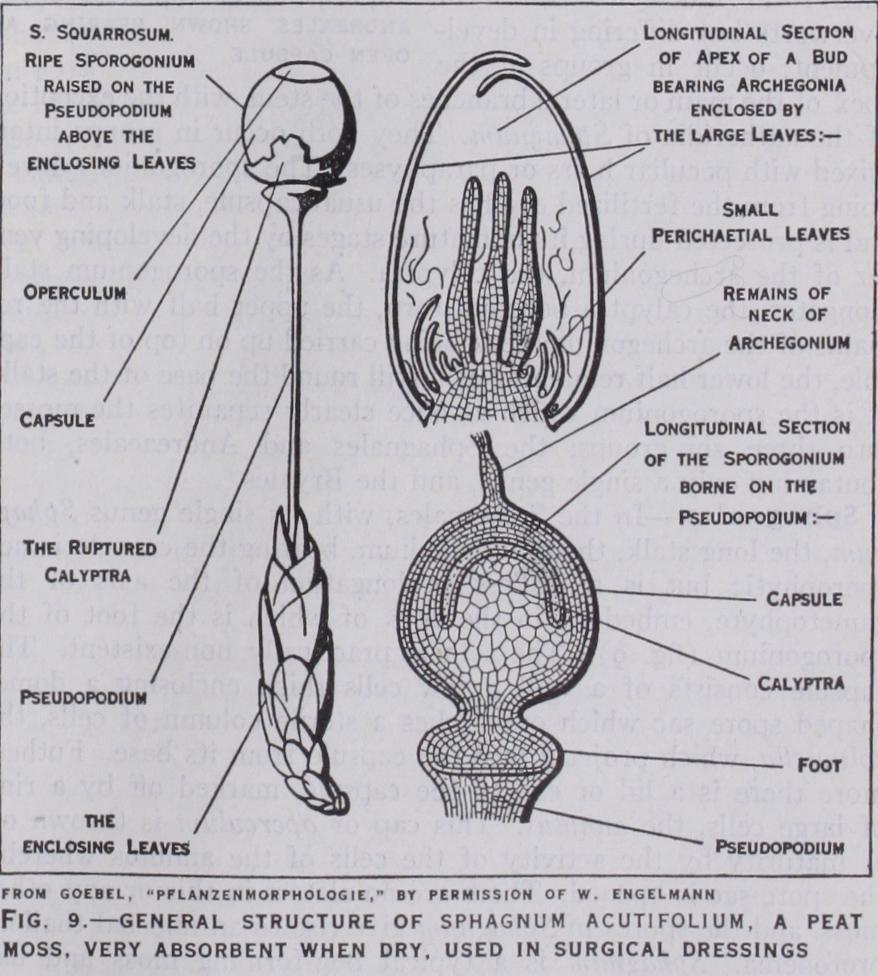

The Anacrogynae afford us the simplest types of the whole group. There is an absolute lack of tissue differentia tion in all forms, but an obvious effort to differentiate in the thallus a rhizomatous portion and a specialized assimilating por tion. The genus Pellia is at once perhaps the most common and certainly the simplest, if one omits Sphaerocarpus and Riella which cannot be here described. In Pellia (fig. 4) the thallus is just like that of the Marchantiales in outline but has no air pores, or chambers, and so appears perfectly smooth and green. No definite ventral scales are formed and no tuberculate rhizoids. These peculiar rhizoids are possessed only by the Marchantiales. The antheridia are spherical bodies borne scattered over the upper part of the thallus ; the same thallus bears archegonia in groups behind the apex and protected by an involucre in the form of a shield of tissue growing up from behind and stretching forward as a little pocket over the archegonia. The sporogonium when mature consists of a basin-shaped foot embedded in the thallus and a long stalk or seta bearing a capsule. Within the wall of the capsule we find spores intermixed with elaters which in Pellia radiate from a column of sterile cells projecting into the capsule from the base, the elaterophore. As a well-developed sheath around the base of the seta may be seen the calyptra, the remains of the archegonium which developed after fertilization and through which the sporogonium burst as the seta elongated. At maturity the spores are discharged by a splitting of the wall of the capsule along four lines from the apex, resulting in four valves which curl back and expose the spores and elaters. With the exception of the elaterophore, the sporogonium of Pellia may be taken as typical of all the Jungermanniales, Anacrogynae and Acrogynae, for its structure is at once exceedingly uniform throughout the group and in sharp contrast with that of the Mar chantiales. In the latter the stalked carpocephalum is gameto phytic tissue whereas in the Jungermanniales the stalk which serves exactly the same purpose is sporophytic tissue.From Pellia as a basal type we can trace in the Anacrogynae an attempt at the assumption of a leafy habit but it never reaches any high degree of organization. The apparent leafiness is rather a result of a more or less pronounced lobing of the thallus or a branching of the thallus. Petalophyllum and Fossombronia (fig.

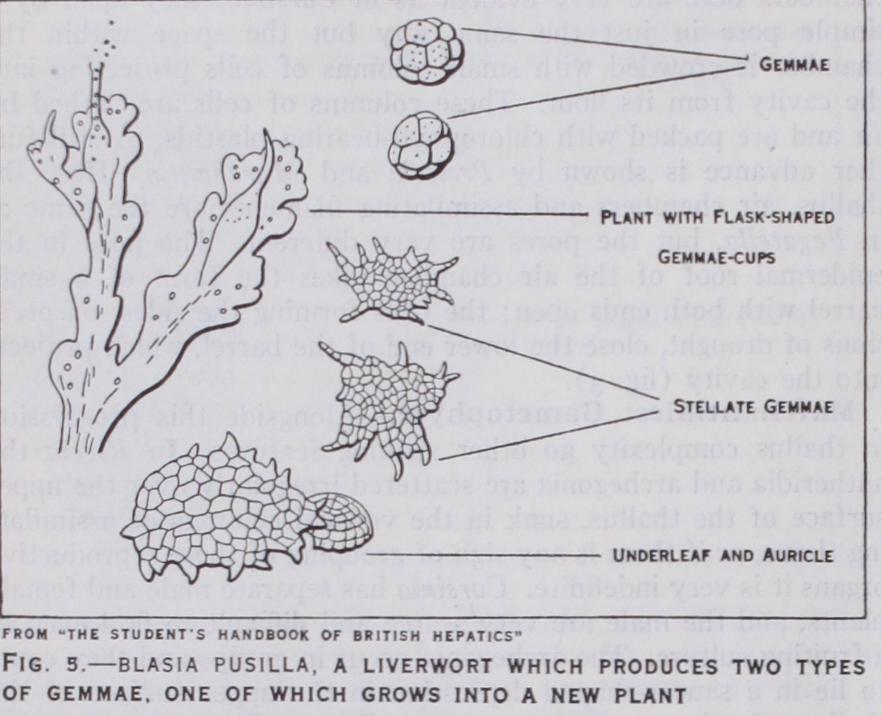

6) give us the best attempt in this direction. Apart from this feature, the Anacrogynae are very uniform in structure ; they differ in detail rather than in basic characters. Many forms pos sess methods of asexual reproduction highly developed. Blasia pusilla (fig. 5), a monospecific genus which very seldom forms sexual organs, is very striking in this respect. This plant produces two types of gemmae, one in the form of little scales which become de tached and grow into a new plant, - the other takes the form of multicellular gem mae produced in large numbers in beautiful "Florence flasks," formed near the apex of branches of the thallus. Aneura and some species of Metzgeria have a peculiar method of non-sexual reproduction, the cells of the thallus producing two non motile gemmae in each cell, their liberation being by breakdown of the cell within which they arose.

The one fundamental fact in their or ganization which sharply distinguishes the Anacrogynae from the Acrogynae is that the apical cell is never involved in the formation of the arche gonia ; in other words the archegonia and sporogonia are never apical on main or lateral shoots, but always dorsal.

Acrogynae.

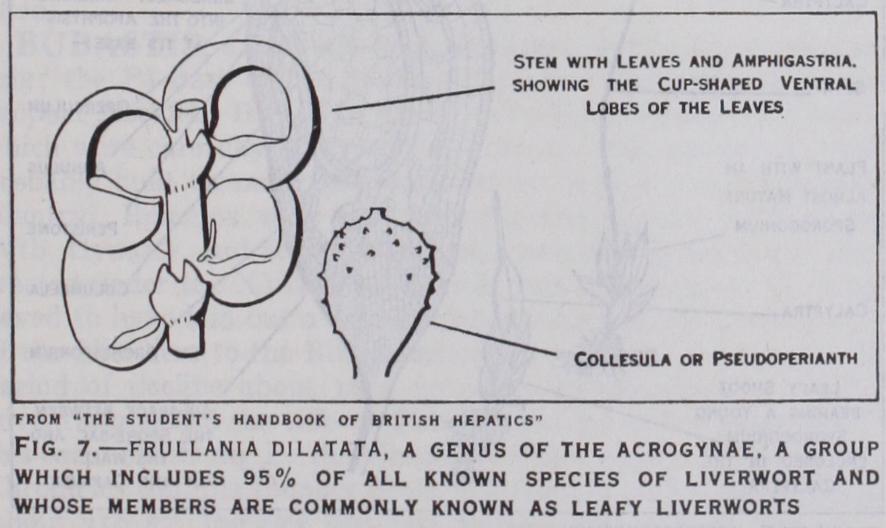

In the Acrogynae, though the antheridia are never apical, the archegonia always are so, on either main or later shoots. The apical cell is used in the formation of archegonia and further growth of the shoot is by a ventral branch. Again the Acroevnae. althoueh includine in their number suite nc% of all known species of liverworts, are very uniform in plan, though differing in detail. They are all leafy types, commonly known as leafy or foliose liverworts. Their leaves are always definitely related to the divisions of the usual three-sided apical cell of the shoot and in their highest development occur in three rows. Of these three rows of leaves two different sets are recog nizable. The Acrogynae are still dorsiventral in habit and two of the three rows of leaves occur in a dorsilateral position, exposed to the light, whilst the third row occurs on the ventral side of the shoot and its members are always smaller in size and usually different in shape from the other leaves. These distinct ventral leaves are called amphigastria (fig. 7). In some cases amphi gastria are absent as in Diplophyllum, Scapania and some Le jeunias. The upper leaves are commonly more or less lobed, a two-pronged leaf being very common and their insertion on the stem is a point of importance. They may be inserted transversely with reference to the axis of the shoot ; they may be obliquely inserted so that the edge of one leaf overlaps the edge of the next—if they overlap like the tiles of a roof they are said to be incubus, if the reverse they are succubus.With regard to sexual organs, some Acrogynae are dioecious, some monoecious, sometimes they occur on special branches, sometimes not. The antheridia are never apical, they always occur in numbers along the stem, most commonly in the axils of leaves of the main shoots, in which case the leaves usually become hol low or hooded and protect them. The archegonia are sometimes on main shoots, sometimes on special shoots ; in either case they always terminate the stem. The leaves near the archegonia are always modified and this modification extends often to three or four pairs of leaves—usually they become larger and simpler than the stem leaves and form the involucre. We often find in forms where amphigastria are normally absent that one is pro duced near the involucre. Very few cases are known where amphi gastria are entirely absent (Scapania). Where they do occur on the stem, in the involucre they are of ten as large as the stem leaves themselves though usually simpler in form. Within the involucre we commonly find a tubular body, the collesula or pseudoperianth (fig. 7), which, though tubular in its origin and development, is referred to a coalescence of three leaves, the two dorso-lateral and the amphigastrium. Few families lack a collesula.

The sporogonia in the foliose liverworts are, apart from detail, much like those in the Anacrogynae, consisting of a foot, long seta and capsule opening by four slits from the apex and containing spores and elaters. A tendency widely spread has been the expan sion of the foot as mentioned in Pellia. This prevalent expansion of the foot is connected with another feature shown by some of the foliose liverworts. The tissue around the foot becomes in volved in the expansion and this ultimately resolves itself into the formation of a conspicuous pouch or rnarsupium which hangs down from the tip of the stem, has many rhizoids on its outer basal portion and within bears the archegonia and subsequently the foot of the sporogonium at the base of the pouch.

Many of the Acrogynae possess wonderful modifications in rela tion to water storage. Tricliocolea, a genus found in sheets at the base of trees in wet tropical jungles, has leaves which are much branched and filamentous, reminding one of the dissected leaves of ordinary water plants. Pouch formation by the leaves is very common. In Frullania (fig. 7) the ventral lobe of the leaf forms a beautiful pouch ; in others, as in some Lejeunias and Radulas the two lobes of the leaf approach to form a cup. Physiotium giganteum has peculiar leaves the ventral lobe of which is just like a bottle, the dorsal lobe being hollowed out and leading directly into the orifice of the bottle. Physiotium acinosum has replaced leaf bottles by collesula bottles, which only rarely con tain archegonia but are solely for water storage.

Anthocerotales.

The Anthocerotales, as mentioned previ ously, possess a simple thallus undifferentiated in either texture or habit, but are sharply sepa rated from the remaining liver worts by reason of their sporo gonium (fig. 8). There are very few genera in the group, the most noted being Anthoceros, Dendro ceros and Notothylas. The thal lus is dark green and its cells contain a single large chloroplast. On the under surface occur small slits filled with mucilage, which often also fills intercellular spaces in the thallus, and colonies of Nostoc, an alga, are con stantly found inhabiting some of the mucilage slits. The group is specially noteworthy on account of its reproductive organs. Antheridia often occur in groups in chambers beneath the epidermis and are endogenous, in contrast to all other antheridia. The archegonia are superficial, but after fertilization become covered over by thallus growth and through this the sporogonium has to burst in its growth. The sporogonium is a remarkable structure. It often reaches a length of an inch or more and consists of a wall several cells thick enclosing a spore sac and a sterile column of cells within, the columella. The spore sac overarches the columella, and besides spores, elaters of irregu lar shape are produced. The most peculiar feature, however, is that although there is no seta, a zone of tissue between the capsule and the foot remains actively growing and is adding new capsule tissues continuously from below during the life of the sporophyte. When mature, the capsule opens in two valves by splitting from the apex, and as spores are shed new ones are being added from the base. Other features of interest are that the wall of the sporo gonium contains stomata and chlorophyll and so can assimilate, and the foot buried in the thallus is irregular in outline. There are slight variations in details of structure between the few forms in this group, yet all are sufficiently peculiar in their structures to warrant the great interest they arouse.