Miisci

MIISCI Musci or mosses, are on the whole more xerophytic (i.e., suited to live under drier conditions) than liverworts and do not offer the same degree of variation in form and structure. All mosses consist of a distinct stem and leaves and almost all of them are radial in construction and not dorsiventral as are liverworts; in fact, apart from differences in smaller details all mosses are fundamentally the same in form (figs. 9, 1o, i I). The stems have a single apical cell, the leaves, too, grow by a two-sided apical cell and do not show any trace of forking as was the case in the leafy liverworts. There is pres ent the possibility of a good deal of differentiation in the tis sues, for some mosses (Poly trichum for instance) reveal a structure almost analogous to the conducting strands of higher plants. The sexual organs, an theridia and archegonia, in ma ture form much like those of liverworts but differing in devel opment, occur in groups at the apex of the main or lateral branches of the stem, with the exception of the antheridia of Sphagnum. They both occur in groups inter mixed with peculiar hairs or paraphyses. The sporogonium devel oping from the fertilized egg has the usual capsule, stalk and foot, and is protected during its immature stages by the developing ven ter of the archegonium, the calyptra. As the sporogonium stalk elongates, the calyptra becomes torn, the upper half with the re mains of the archegonium neck being carried up on top of the cap sule, the lower half remaining as a frill round the base of the stalk. It is the sporogonium which at once clearly separates the mosses into three sub-groups, the Sphagnales and Andreaeales, both containing only a single genus, and the Bryales.

Sphagnales.

In the Sphagnales, with its single genus Sphag num, the long stalk, the pseudopodium, bearing the capsule is not sporophytic but is a leafless prolongation of the axis of the gametophyte, embedded in the apex of which is the foot of the sporogonium (fig. 9). The seta is practically non-existent. The capsule consists of a wall a few cells thick enclosing a dome shaped spore sac which overarches a sterile column of cells, the columella, which projects into the capsule from its base. Futher more there is a lid or cap to the capsule, marked off by a ring of large cells, the annulus. This cap or operculum is thrown off at maturity by the activity of the cells of the annulus whereby the spore-sac is opened. There are no elaters in this or any other moss, and the spores in Sphagnum give rise to an unusual thalloid protonema. Sphagnum is a typical bog-forming moss and has leaves with very peculiar structure. These are one cell thick and consist of large, colourless empty cells open to the exterior by a pore, and surrounded by the comparatively small narrow chloro phyll-containing cells. The presence of these empty cells renders Sphagnum very absorbent, whence its use in surgical dressings.In the Andreaeales, with its single genus Andreaea (fig. zo), again the sporogonium is borne aloft on a pseudopodium and the dome-shaped spore sac overarches the columella as in Sphagnum. Here, however, there is no operculum, the mature sporogonium opening by four slits down the side of the capsule.

Bryales.

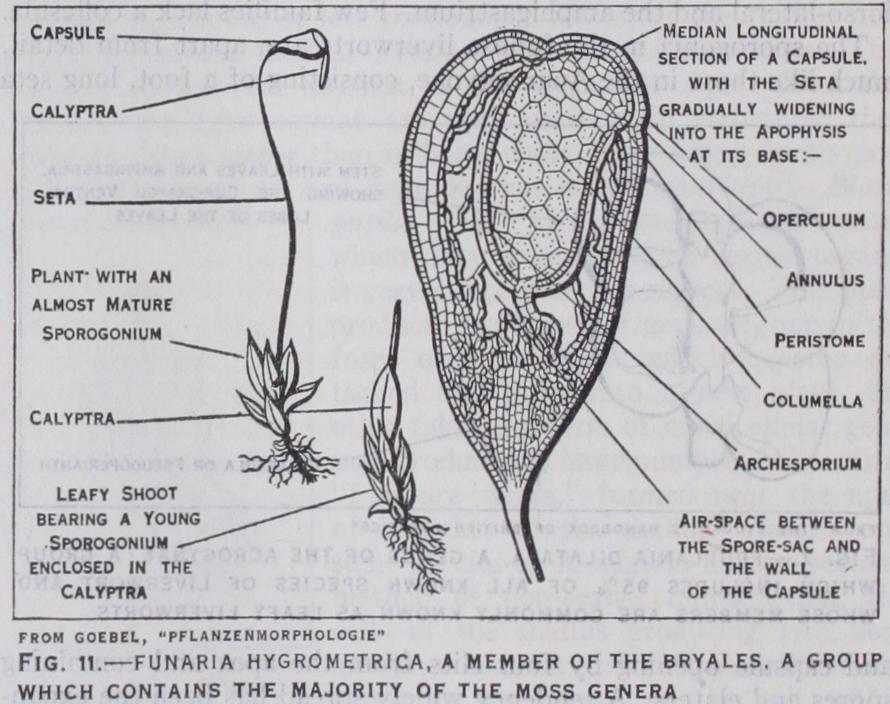

The Bryales afford the most complicated structure of the sporophyte. Here the capsule is, with very few exceptions, borne on a long seta at whose base, sunk in the apex of the stem of the gametophyte, is the foot. The capsule is remarkable in many respects (fig. i 1). The wall is several cells thick, and there is a well-defined operculum delimited by an annulus. Within the capsule running from base to apex is a sterile column of cells, the columella, which is surrounded by the cylindrical spore sac. Surrounding the spore sac is an air chamber, the spore sac being connected with the wall by means of strands of cells or trabeculae. The wall of the capsule possesses stomata and its cells contain chlorophyll, so that the sporophyte here can assimilate to some extent. At the apex of the seta, adjoining the capsule, is a region highly developed in some forms (Splachnum luteum) which has abundant air spaces and stomata in its epidermis, a region known as the apophysis. More remarkable, however, is the peristome of the capsule. This consists of one or two layers of small teeth attached to the wall of the capsule just beneath the annulus at one end, but free elsewhere. When the capsule is mature and the operculum thrown off, these teeth close the now hollow spore containing capsule when conditions are moist and so retain the spores, but curl back in dry weather and allow their discharge.This structure of the sporogonium is fairly uniform through out the Bryales with the exception of the condition seen in the Polytrichaceae where peristome teeth are not developed, the cap sule when mature having a ring of pores in place of the peristome. It is not necessary to stress the obvious fact that in the Bryales sporogonium we have a very highly organized structure.

Space does not permit even mention of the many points of theoretical interest in the Bryophyta, or many unusual but inter esting forms to be met with. These questions, with others which add to the interest of the group, may be followed in the literature cited. The Bryophyta play their part in questions of broader interest. A few, for instance, act as "colonisers," they can gain a foothold on bare rock or other uncongenial places where higher plants fail, and in this way in course of time prepare a suitable groundwork for these higher forms. Many mosses and liverworts are epiphytic on the stems or leaves of other plants and it is interesting that many of them are very specific in their choice of host. Therein lies an unsolved problem and there is need for careful recording of observations in this respect.

As to the origin of the Bryophyta as a whole, opinion is divided. We have little or no positive evidence from living or fossil forms, neither can we say definitely which of the higher groups of plants arose from them. Within themselves, as has been pointed out, they do show a serial progression, although instances of reduction are undoubtedly to be found. Such instances of reduction in structure have led some bryologists to look upon the simpler forms as derived from the higher by reduction, though this view is generally considered to be contrary to the mass of evidence. Between the Hepaticae, Anthocerotales, Sphagnales and Bryales there are no connecting forms known, and it must be left as an open question whether Bryophyta are a monophyletic group or not. With regard to the relationship between Bryophyta and Pteridophyta the article on the latter group should be consulted. Although the alternating generations in the two are strictly comparable, no evidence of actual relationship is yet advanced. For further information consult: Campbell, Mosses and Ferns (1895) ; Engler and Prantl, Die naturlichen Pfianzenfamilien, Teil I. Alt. 3 (Leipzig, 1909) ; Goebel, Organography of Plants (1900 and 1905) ; Cavers, "Inter-relationships of Bryophyta," New Phytologist (Reprint, Cambridge, 1911) .

For identification of British species of liverworts and mosses:— Braithwaite, British Moss Flora (1887-1905) ; Pearson, The Hepaticae of the British Isles (1902) ; Dixon and Jameson, The Student's Hand book of British Mosses (1904) ; MacVicar, The Student's Handbook of British Hepatics (Eastbourne and London, 1926). (F. How.)