Military Bridging

BRIDGING, MILITARY. In the course of most military operations it is necessary to cross rivers at places where no bridges exist or where they have been demolished by the enemy. It is the duty of the engineers of an army to provide the means for such crossings. For small detachments ferrying with boats or rafts is resorted to, but for forces of any size accompanied by artillery and transport bridges must be built. Floating bridges are the most rapidly built and have consequently been most frequently employed ; they are built either with material obtained locally or with special "pontoon" equipment accompanying the army on wagons. Many other types of construction have been employed such as trestle bridges in which the roadway is supported by a series of timber trestles, cribwork bridges in which the supports consist of timber cribs usually filled with stone, pile bridges, sus pension bridges and steel or wooden girder bridges. So long as transport and guns were drawn by animals the weight of vehicles was limited and consequently the strength required of military bridges remained approximately constant until the beginning of the loth century. With the introduction of motor vehicles and tanks, however, weights increased enormously and all bridging standards had to be reconsidered.

From time immemorial floating bridges of vessels bearing a roadway of beams and planks have been employed for the passage of rivers and arms of the sea. Xerxes crossed the Hellespont on a double bridge, one line supported on 36o, the other on 314 vessels anchored head and stern with their keels in the direction of the current. Darius threw similar bridges across the Bosphorus and the Danube in his war against the Scythians, and the Ten Thou sand employed a bridge of boats to cross the river Tigris in their retreat from Persia. Floating bridges have been repeatedly con structed over rivers in Europe and Asia, not merely temporarily for the passage of an army, but permanently for the requirements of the country; and to this day many of the great rivers in India are crossed by floating bridges which are for the most part sup ported on boats such as are employed for ordinary traffic on the river. Alexander the Great is said to have carried his army over the Oxus by means of rafts made of the hide tents of his soldiers stuffed with straw when he found that all the river boats had been burnt. Cyrus crossed the Euphrates on stuffed skins. In the 4th century the emperor Julian crossed the Tigris, Euphrates and other rivers by bridges of boats made of skins stretched over osier frames. In more recent times bridges have been supported on floating piers made of barrels lashed together. During the World War light footbridges for the assaulting infantry were frequently made supported by floats composed of cork or empty petrol tins held together in light crates. Bivouac sheets stuffed with straw were also used as in the days of Cyrus and Alexander.

Principles of Pontoon Equipments.

All the devices men tioned above are still occasionally used but they depend upon materials to be found on the spot and these are rarely available in sufficient quantities and furthermore take time to collect. For these reasons pontoon equipments were introduced. Such equip ments consist of sets of stores designed for the construction of floating bridges; packed on wagons they accompany an army and are available for use wherever required. There are three essential parts, floating supports called "pontoons" anchored at intervals in the stream with their keels in the direction of the current ; beams called "baulks" or "road-bearers" spanning the intervals between pontoons and supporting the roadway; and finally the roadway itself composed of planks technically known as "chesses." To understand the history of their development the qualities desirable in these parts must first be considered.The pontoons must have sufficient buoyancy to support the loads which are to use the bridge ; within limits the power of support can be increased by placing them closer together, but in rapid currents the water-way must not be unduly obstructed or the bridge will be washed away. They must be light enough to be man handled and to be loaded upon wagons. They must be strong enough to withstand rough usage and should be easily repairable in the field. These requirements are contradictory and the history of pontoon design is a history of compromise. The most usual form is that of a flat-bottomed boat either with or without a deck; decked it can with safety be more deeply loaded, but its interior is inaccessible and it is less convenient for use as a boat.

The road-bearers must be strong enough to support the road way, and must also be as light as possible for transport. Evi dently, the greater the intervals between the pontoons the greater the strength required. They may rest either on a central saddle placed longitudinally on each pontoon vertically above the keel— "saddle loading"—or simply upon the gunnels of the pontoons— "gunnel loading." Saddle loading makes for great simplicity in constructing the bridge, each set of road-bearers spanning from the centre of one pontoon to the next with claws or pins on their ends which engage in the saddles. Gunnel loading does not require such strong road-bearers since the spans are shorter; it also adds stiffness to the bridge, but the fastenings are more complicated. Until the advent of mechanical transport wooden road-bearers about Sin. by 4in. in section and 15 to 2oft. long were usually employed.

The chesses must be as light as is consistent with strength. In the days of horse-drawn traffic I lin. was the usual thickness; for heavy traffic a second layer was laid on top of the first.

History of Pontoon Equipment.

Alexander the Great occa sionally carried with his army vessels divided into portions which were put together on reaching the banks of a river, as in crossing the Hydaspes. The practice of carrying about skins to be inflated when troops had to cross a river was adopted by the Greeks, the Romans and the Mongols and indeed still exists in the East. In the wars of the 17th century pontoons are found as regular com ponents of the trains of armies, the Germans using a leather, the Dutch a tin and the French a copper "skin" over stout timber frames. In the middle of the i8th century the Russians introduced a collapsible pontoon consisting of a tarpaulin skin stretched on a wooden frame. For transport the frame was dismantled and the tarpaulin rolled up; this type they retained for a hundred years.During the 19th century a great number of designs were intro duced only a few of which can be mentioned here. No army had more experience of pontooning than the French; during the wars of the Revolution and the Empire they constructed pontoon bridges over most of the principal rivers of Europe. They experi mented with many types ranging from large wooden boats weigh ing about 2 tons to small copper ones weighing 7cwt. ; the heavy wooden type, the Gribeauval, was discarded in 18o5 as it could not keep up with the movements of the armies; in 1853 they adopted a flat-bottomed open wooden boat 3i ft. long and weighing 1,45o lb., which appears to have been very successful and was exten sively used by the Northern States during the American Civil War.

During the Peninsular War the English employed open pontoons, but the experience gained during that war induced them to intro duce the closed form. Gen. Colleton devised a buoy pontoon, cylindrical with conical ends and made of wooden staves like a cask. Then Gen. Sir Charles Pasley introduced demi-pontoons, like decked canoes with pointed bows and square sterns, a pair, attached stern-wise, forming a single "pier" of support for the roadway; they were constructed of light timber frames covered with sheet copper and were decked with wood ; each demi-pontoon was divided into watertight compartments and provided with means for pumping out water ; for transport a pair of demi-pon toons and the superstructure for one bay of bridge were loaded on, a single wagon. The Pasley was superseded by the Blanshard pontoon, a tin-coated cylinder with hemispherical ends for which great mobility was claimed, two pontoons and two bays of super structure being carried on one wagon. The Blanshard pontoon was long used in the British army, but was ultimately discarded, and British engineers reverted to the open pontoon to which the engineers of all the Continental armies had meanwhile constantly adhered. Capt. Fowke, R.E., invented a folding open boat made of waterproof canvas attached to sliding ribs, so that for trans port it could be collapsed like the bellows of an accordion and for use could be extended by a pair of stretchers. This was fol lowed by a pontoon designed by Col. Blood, R.E., an open boat with decked ends and sides partly decked where the rowlocks were fixed. The sides and bottom were of thin yellow pine with canvas secured to both surfaces with india-rubber solution, and coated outside with marine glue. The central interval between the pon toons in a bridge was r 5f t.; five baulks were ordinarily used, nine for the passage of siege artillery and the heaviest loads ; saddle loading was employed. One pontoon with one bay of superstruc ture were loaded on a wagon. This equipment was later modified by the introduction of an undecked bipartite pontoon designed in 1889 by Lieut. Clauson, R.E. As its name implies this pontoon was in two sections, a bow section and a stern section, coupled together with easily manipulated couplings of phosphor bronze. For light bridges the sections could be used independently; for heavy bridges three sections could be coupled together end to end. Except for minor modifications this equipment was retained in the British service until 1924. During the World War it was much used in Mesopotamia and during the early and final stages in France ; it was found unsuitable in the rapid current of the Piave on the Italian front.

Historically the most important equipment is that introduced in the Austrian army by Col. Birago in 1841 ; it was either adopted or copied by many other armies. The Birago pontoon was a flat bottomed open boat constructed in sections two or more of which could be coupled together end to end to form piers of the buoy ancy required. This idea had first been proposed by Col. Pompei Floriani about the middle of the 17th century but had not pre viously been fully developed ; as already mentioned it was subse quently adopted in British equipments. The Birago pontoons were in the first instance made of wood, later they were made en tirely in iron and later still in steel. One reason given for the change was that metal pontoons were more easily repaired in the field than wooden ones ; this argument, however, would not gen erally be accepted. Saddle loading was adopted, the saddle being arranged to slew in the pontoon so that a bridge could be built diagonally across a river, the pontoons still pointing in the direc tion of the current ; great importance was attached to this feature at the time but it was not subsequently found to be practical.

An interesting equipment was introduced into the American army in 1846. The pontoons were made entirely of india-rubber and each consisted of three parallel pointed cylinders croft. long joined together side by side by an india-rubber web. When the pontoon was required for use these cylinders were inflated through nozzles with a pair of bellows ; for transport the entire pontoon was folded up and packed in a box. After considerable experience during the American Civil War the engineers of the Northern States much preferred the French equipment.

Methods of Bridge Building with Pontoon Equipment.— There are f our recognized methods of building pontoon bridges; the choice depends partly upon the actual equipment in use and more upon the site of the bridge and nature of the river. (a) "Forming up." In this method pontoons are added successively to the "head" or far end of the bridge and the roadway added on top of them; this is perhaps the simplest method. (b) "Boom ing out." Pontoons are added successively at the "Tail" or shore end and the whole bridge pushed out, this saves carrying all the stores for the roadway to the far end of the bridge. (c) "By rafts." Complete sections of the bridge are built in convenient positions by the near bank, floated into position and joined to gether; this method will often be quicker than (a) or (b). (d) "Swinging Bridge." The entire bridge is built alongside the near bank, that is, at right angles to its final position; when complete it is allowed to swing round with the current on its near end as a pivot, anchors are dropped in their appropriate positions as it swings and the entire bridge is checked by the anchor cables as it reaches its correct alignment. On a suitable site this method is extremely rapid, but in fast streams the operation is risky and the bridge often is lost or severely damaged.

Trestle Bridges.

It is not always feasible to construct a floating bridge, pontoons may not be available, the water may be too shallow or the gap may be entirely dry. In such cases tim ber trestles have frequently been used to replace pontoons as supports for the road-bearers. Such trestles consist essentially of a horizontal bottom piece or "ground sill," two or more legs which are vertical or slightly inclined inwards at the top, and a horizontal top piece or "transom" on which the ends of the road-bearers rest as they would on the saddle of a pontoon; the whole is stiffened up by diagonal braces. The size of the timber used varies with the nature of the bridge, ranging from light army signal poles used for the trestles of infantry assault bridges during the World War to timber baulks i 2in. square or even larger used for railway bridges during the American Civil War and the Boer War and for heavy road bridges during the World War. In the case of light and very temporary trestles the members may be fastened together by means of wire or even rope lashings, but where any strength or permanency are required they must be properly fitted and spiked or dogged together. High railway viaducts have been built by placing two or even three heavy trestles on top of each other to form each pier and bracing the whole together. Trestles are usually constructed on shore, carried into position and up-ended ; in the case of the heaviest trestles derricks have to be employed. After losing his pontoons in the retreat from Moscow Napoleon crossed the Beresina on a trestle bridge. The trestles were placed by hand by men working waist deep in the icy water. Most pontoon equipments have included specially designed trestles for use where the water close to the shore is not deep enough to float a pontoon.

Cribwork.

Timber cribs have been used instead of trestles for railway and heavy road bridges when timber was plentiful and the height required small. They were much used during the Boer War in the repair of demolished railway bridges, railway sleepers being employed in their construction. Timber crib construction is very convenient since no skilled labour is required but cribs are wasteful of material. When placed in water they are usually spiked together and filled with stone. During the World War 3ft. cubes made of light steel angles riveted together were kept as an article of store and extensively used for building up piers of moderate height for heavy road bridges. An instance occurred in 1918 in the crossing of the Selle where, under the nose of the enemy holding the opposite bank, a crib causeway for tanks, built of railway sleepers, bolted together and sunk in the bed of the river was con structed during the nights immediately preceding the attack and kept concealed from view and from aerial photography by being completed just below water-level.

Pile Bridges.

Trestles or Cribwork are often not feasible in rapid currents owing to the scour and if pontoon equipment is not available pile driving has to be resorted to, but it is a slow method. In 1809, before the battle of Wagram, Napoleon's engineers under Gen. Bertrand constructed a pile bridge 800yd. long across the Danube at Vienna in 20 days ; upstream, piles were driven to form a "boom" to protect the bridge from floating bodies sent down by the enemy.Girder Br idges.—Unlike the types described above girder bridges can span clear gaps of iooft. or more without any inter mediate support. They were first extensively used during the World War in France. Standard patterns were manufactured in large quantities, parts were as far as possible interchangeable and bridges could be built of any multiple of the fixed panel length up to a maximum which depended on the loads which were to use them. The Hopkins type of girder bridge and the Inglis were the most important types; both were "through" bridges, the roadway being carried between two Warren girders. The Hopkins followed the lines of ordinary civil practice except that bolts were substi tuted for rivets to facilitate erection in the field. In the Inglis the principal members were tubular and were connected into special cast junction pieces by pins and locking rings. The method usually employed was to build the bridge on dry land in rear of the gap and then launch it over rollers by means of derricks and winches on the far bank.

Assault Bridging.

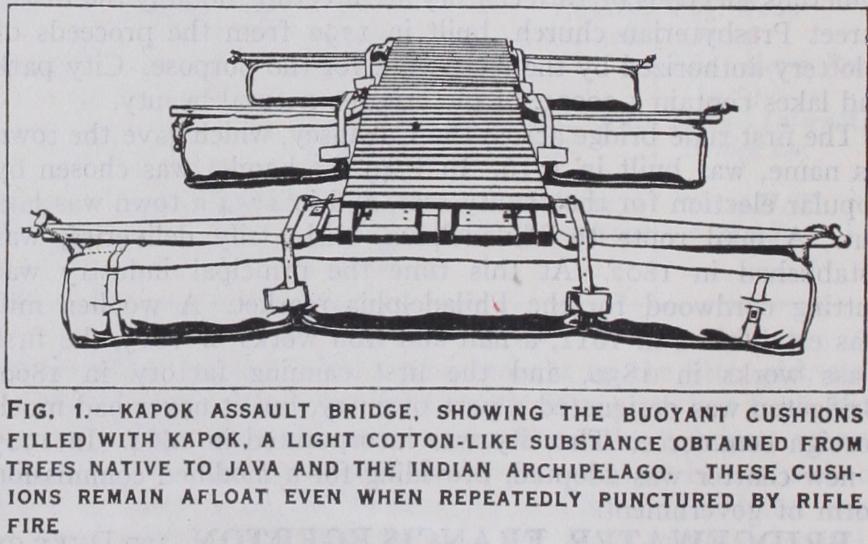

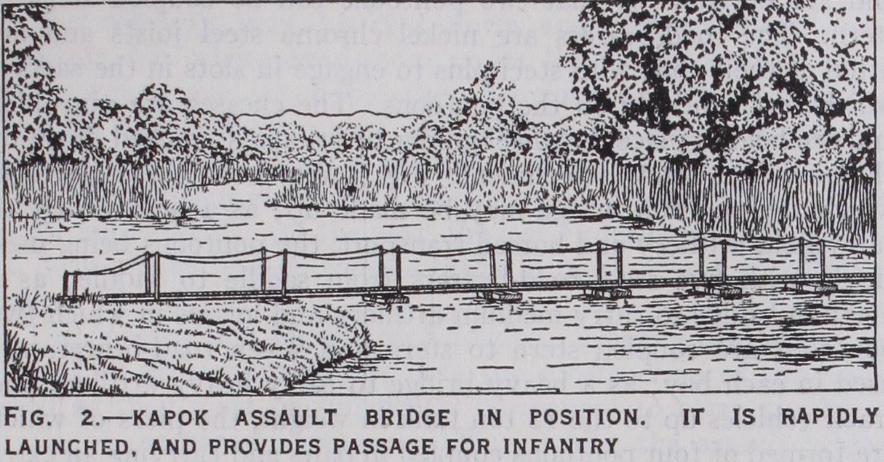

Forcing the passage of a river in the face of the enemy is a difficult operation under modern conditions. It will usually be necessary to pass the assaulting infantry over as rapidly as possible under cover of darkness and without making any preparations which would put the enemy on his guard. The use of improvised floating assault bridges during the World War has been referred to above. A special equipment for this purpose has since been introduced into the British service ; it is known as the kapok assault bridge and is shown in figs. i and 2. This bridge consists of canvas floats stuffed with kapok, each bearing, strapped to it, a transom plate or saddle with a metal coupling to which are affixed the timber duckboards which form the bridge from float to float. At each end of the floats are handles so that the bridge, after being assembled at a convenient spot near the river, can be lifted bodily by two men for each float and carried forward for launching.The operation of launching and pushing the bridge across the river can be effected in a few seconds, and as soon as it has been secured on the far bank the assaulting infantry can commence to cross. The articulation of the saddle joint allows sufficient play for the bridge to be carried and launched over rough ground whilst providing sufficient lateral rigidity to steer its head across the stream, even against cross-wind and current. The buoyancy of the floats is ample and the bridge is stable in the water. The virtue of the kapok float lies in its lightness and in the fact that it is little affected by rifle fire ; even when repeatedly punctured it absorbs water very slowly. For the formation of a bridge to take pack transport three kapok assault bridges are placed side by side and planked over to form a roadway.

Pontoon Equipments.

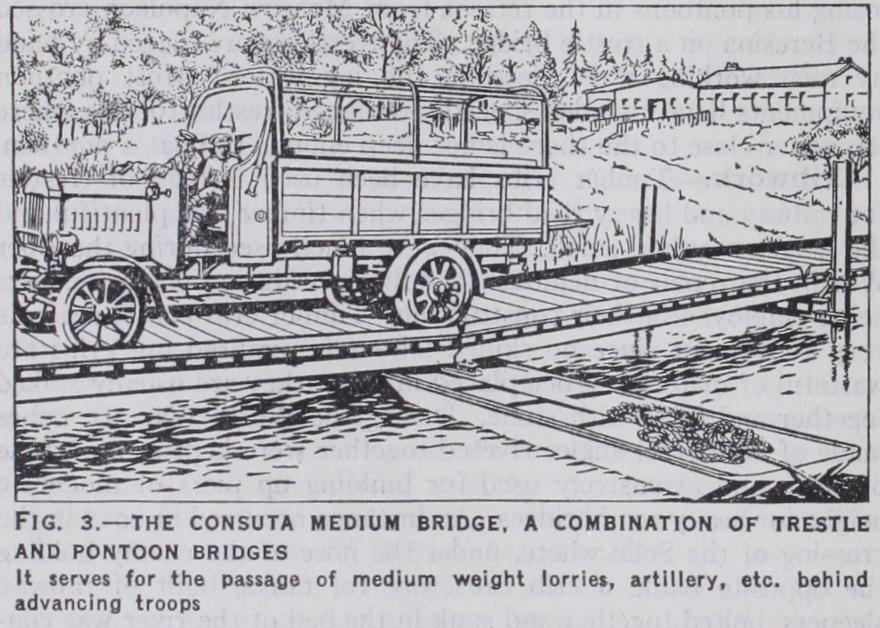

Prior to 1914 the majority of mili tary transport was still horse-drawn and vehicles weighed about 2 tons. The weight of field guns and howitzers was of the same order and heavier artillery was an exception for which it was not usually necessary to provide. The horse-drawn wagon has now been replaced by the motor lorry weighing four times as much. Medium and heavy artillery are common and tanks weighing 12 tons or more must be passed across rivers with the minimum of delay. It has therefore been necessary to redesign pontoon equip ments. The pattern adopted in the British service is shown in fig. 3. The pontoons are flat-bottomed boats with scow bows and are completely decked in, they are 21 ft. long, 5f t. 6in. wide and aft. 9in. deep and weigh about 1,400 lb. They are built with a skin of two or three ply consuta wood on a mahogany framework and are designed so that two pontoons can be coupled stern to stern. The road-bearers are nickel chrome steel joists and are fitted at their ends with steel pins to engage in slots in the saddles which rest centrally on the pontoons. The chesses are Sin. thick and are held in place by wheel guides or "ribands" racked down by chains with a screw attachment. Fig. 3 shows the three forms in which the pontoon bridge may be made up; as a light bridge to carry field artillery and horsed transport, the pontoons being used singly with five steel road-bearers from saddle to saddle ; as a medium bridge to carry medium artillery and lorries in which two pontoons are coupled stern to stern and seven road-bearers are used in each bay ; as a heavy bridge to carry heavy artillery and track vehicles up to the 18 ton tank in weight, the piers of which are formed of four pontoons coupled in pairs and carrying an extra central saddle on which II road-bearers are placed to carry the roadway. In all forms each bay of bridge spans 21 feet. A steel trestle is provided as part of the equipment. It consists of two mild steel legs with pitch pine mud shoes, a nickel chrome steel transom and two jacks for raising or lowering the transom. The legs are drilled with holes along the centre of the web into which the pins of the transom engage so that the transom and, with it, the roadway can be raised or lowered by means of the jacks as occasion requires. When used in conjunction with a heavy bridge as shown in fig. 2, a double trestle pier is formed, but with a medium bridge a single trestle suffices to form a pier.The French have adopted an undecked pontoon made of gal vanized steel sheet on a steel framework; it is 33 f t. long, 6f t. 6in. wide and aft. Sin. deep, weighs 2,420 lb. and is designed for gun nel loading. Experiments have been carried out with two systems of construction. In the first ordinary wooden road-bearers are used and lashed down to the pontoons ; in the second an ingenious arrangement of articulating steel girders is added outside the roadway on each side to distribute the load between pontoons; the road-bearers in this case are of steel.

It will be seen that there is still wide divergence of opinion as to the best design for a pontoon equipment; on the whole it may be said that the metal pontoon is, in spite of its weight, gaining ground at the expense of the wooden one; that the boat-shaped pontoon has asserted its superiority over all other designs; and that decked pontoons are in the minority. Opinion on saddle versus gunnel loading is divided. Experiments with aluminium alloy pontoons have been undertaken in several countries, but nowhere have the practical difficulties yet been overcome.

Girder Bridges.

Steel girders are required for semi-perma nent bridges on the lines of communication since pontoon equip ment requires too much attention to, be satisfactory for this pur pose and will in any case be required to move forward with the army. It will be realized from the description given of them above that the Hopkins and the Inglis bridges required considerable time and skilled labour to erect. These objections have been largely overcome in the Martel box girder bridge (fig. 6 of the plate) since introduced into the British service. This is designed to enable all spans up to about iooft. to be bridged in the simplest manner and also to secure that the bridge so built will be strong enough to carry either light, medium or heavy loads. The bridge is of the deck type and the chesses lie flat on the top of the box girders. The girders are skeleton steel boxes made up in sections, each 8ft. long. The sections are joined together by plain pin joints; no nuts or bolts are required. There are thus only two essential parts, viz., the box girders and the chesses.Three types of bridge can be built by using two, three or four box girders under the chesses. In fact the gap is to all intents and purposes spanned by using skeleton steel road-bearers which can be made up to any desired length in 8ft. sections. To obtain a wider bridge it is merely necessary to add more box girders and use longer chesses, or a double row of chesses. The decking is held in position by angle steel kerbs fixed down by hook bolts, and the handrail consists of posts which fit into the sockets in the centre of each 8ft. length of kerb and piping. The handrail pipes are also used as carrying bars for carrying sections of the girders. The girders will usually be fitted with horn beams at each end, a construction which enables them to be lowered on to masonry abutments, or on to a timber bankseat so that the level of the roadway may be kept down and a ramp-up approach avoided; but where head-room under the bridge is required or the approach level is suitable, these are not necessary. The girders may be launched by means of a derrick on the far bank or a cantilever method may be adopted if the bridge is a heavy one with three or four girders. In this case each girder is used in turn as a counter-weight for the next, the last girder being rolled across on deck planks laid on those already in position and then jacked down.

The construction of approach roads to a heavy bridge is often a work of greater magnitude than the construction of the bridge itself as they must be sufficiently permanent to carry the heavy strain of mechanical transport. Thus, whilst the assault bridges are intentionally thrown well away from the main lines of traffic and the lighter forms of pontoon bridge can be used wherever a reasonable cross country approach track can be made, the heavy bridges are confined closely to the route of the main roads.

Probable Effect of Mechanical Warfare.

Mechanical war fare is still in its infancy and the direction of its future develop ment is uncertain. The effect on military bridging is therefore a matter of speculation. One of the chief assets of a mechanical force of tanks, armoured cars, etc., is its speed and power of move ment over favourable ground independently of roads. Obviously it will frequently use this mobility to go round obstacles instead of spending time constructing bridges. Unless, however, it is pro vided with some means of rapidly crossing streams of moderate width much of the value of its mobility will be lost.See Official army manuals on bridging (English, French, American, etc.), which are the best source of information. The Work of the Royal Engineers in the European War 1914-1919, Bridging, Institution of Royal Engineers, Chatham (1921) , contains interesting photo graphs. (R. D. D.)