Robert Burns

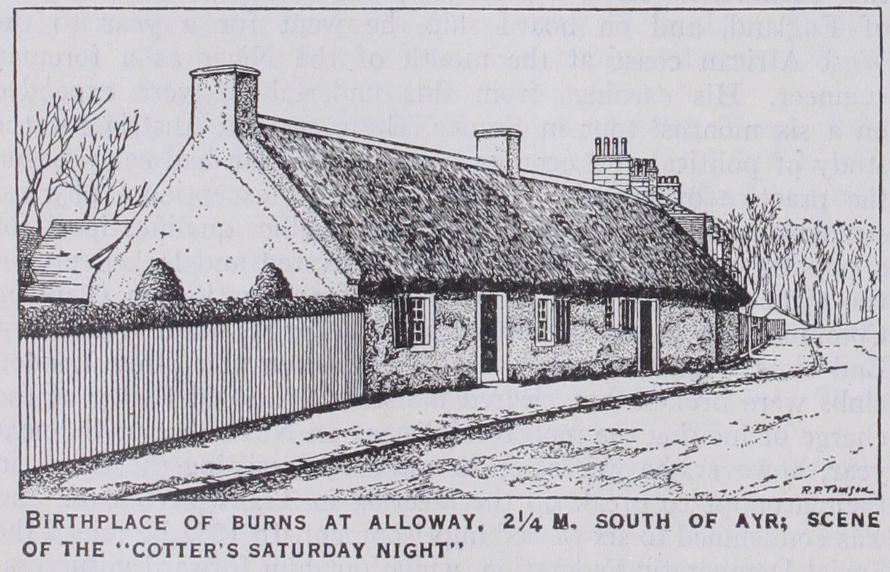

BURNS, ROBERT (1759-1796), greatest of Scottish poets, was born on Jan. in a cottage about am. from Ayr. He was the eldest son of a small farmer, William Burness, of Kincardineshire stock. "The poet," said Thomas Carlyle, "was fortunate in his father—a man of thoughtful, intense character, as the best of our peasants are, valuing knowledge, possessing some and open-minded for more, of keen insight and devout heart, friendly and fearless : a fully unfolded man seldom found in any rank in society, and worth descending far in society to seek. . . . Had he been ever so little richer, the whole might have issued otherwise. But poverty sank the whole family even below the reach of our cheap school system, and Burns remained a hard-worked plough-boy." Through a series of migrations from one unfortunate farm to another; from Alloway (where he was taught to read) to Mt. Oliphant, and then (17 7 7) to Lochlea in Tarbolton (where he learnt the rudiments of geometry), the poet remained in the same condition of straitened circumstances. At the age of 13 he thrashed the corn with his own hands, at 15 he was the principal labourer. "This kind of life," he writes, "the cheerless gloom of a hermit and the unceasing toil of a galley-slave, brought me to my 16th year." His naturally robust frame was overtasked, and his nervous constitution received a fatal strain. His shoulders were bowed, he became liable to headaches, palpitations and fits of depressing melancholy. From these hard tasks and his fiery temperament, craving in vain for sympathy in a frigid air, grew a thirst for stimulants and revolt against restraint. Sent to school at Kirkoswald, he became, for his scant leisure, a great reader— eating at meal-times with a spoon in one hand and a book in the other—carrying a few small volumes in his pocket to study in spare moments in the fields. "The collection of songs," he tells us, "was my vade mecum. I pored over them driving my cart or walking to labour, song by song, verse by verse, carefully noting the true, tender, sublime or fustian." He lingered over the ballads in his cold room by night ; by day, whilst whistling at the plough, he invented new forms and was inspired by fresh ideas, "gather ing around him the memories and the traditions of his country till they became a mantle and a crown." Burns had written his first verses of note, "Behind yon hills where Stinchar (afterwards Lugar) flows," when in 1782 he went to Irvine to learn the trade of a flax-dresser. "It was," he says, "an unlucky affair. As we were giving a welcome carousal to the New Year, the shop took fire and burned to ashes; and I was left, like a true poet, without a sixpence." His own heart, too, had unfortunately taken fire. He was poring over mathematics till, in his own phraseology—still affected in its prose by the classical pedantries caught from Pope by Ramsay—"the sun entered Virgo, when a charming fillette, who lived next door, overset my trigonometry, and set me off at a tangent from the scene of my studies." The poet was jilted, went through the usual despairs, and resorted to the not unusual sources of con solation. He had found that he was "no enemy to social life," and his mates had discovered that he was the best of boon companions in the lyric feasts, where his eloquence shed a lustre over wild ways of life, and where he was beginning to be dis tinguished as a champion of the New Lights and a satirist of the Calvinism whose waters he found like those of Marah.

In Robert's 25th year his father died, full of sorrows and apprehensions for the gifted son, who wrote for his tomb in Alloway kirkyard, the fine epitaph ending with the characteristic line— For even his failings leaned to virtue's side.

For some time longer the poet, with his brother Gilbert, lingered at Lochlea, reading agricultural books, miscalculating crops, attending markets, and in a mood of reformation resolving, "in spite of the world, the flesh and the devil, to be a wise man." Affairs, however, went no better with the family; and in 1784 they migrated to Mossgiel, where he lived and wrought, during four years, for a return scarce equal to the wage of the common est labourer in our day. Meanwhile he had become intimate with his future wife, Jean Armour; but the father, a master mason, discountenanced the match, and the girl being disposed to "sigh as a lover," as a daughter to obey, Burns, in 1786, gave up his suit, resolved to seek refuge in exile, and having accepted a situation as book-keeper to a slave estate in Jamaica, had taken his passage in a ship for the West Indies. His old associations seemed to be breaking up, men and fortune scowled, and "hungry ruin had him in the wind," when he wrote the lines ending— Adieu, my native banks of Ayr, and addressed to the most famous of the loves, in which he was as prolific as Catullus or Tibullus, the proposal— Will ye go to the Indies, my Mary.

He was withheld from his project and the current of his life was turned by the success of his first volume, which was pub lished at Kilmarnock in June, 1786. It contained some of his most justly celebrated poems, the results of his scanty leisure at Lochlea and Mossgiel; among others "The Twa Dogs"—a graphic idealization of Aesop—"The Author's Prayer," "The Address to the Deil," "The Vision," "The Dream," "Hallowe'en," "The Cotter's Saturday Night," the lines "To a Mouse" and "To a Daisy," "Scotch Drink," "Man was made to Mourn," the "Epistle to Davie," and some of his most popular songs. This epitome of a genius so marvellous and so varied took his audience by storm. "The country murmured of him from sea to sea." "With his poems," says Robert Heron, "old and young, grave and gay, learned and ignorant, were alike transported. I was at that time resident in Galloway, and I can well remember how even plough-boys and maid-servants would have gladly bestowed the wages they earned the most hardly, and which they wanted to purchase necessary clothing, if they might but procure the works of Burns." This first edition only brought the author £20 direct return, but it introduced him to the literati of Edinburgh, whither he was invited, and where he was welcomed, feasted, admired and patronized.

Sir Walter Scott bears testimony to the dignified simplicity, and almost exaggerated independence of the poet, during this annus mirabilis of his success. "As for Burns, Virgilium vidi tantum, I was a lad of 15 when he came to Edinburgh, but had sense enough to be interested in his poetry, and would have given the world to know him. I saw him one day with several gentle men of literary reputation, among whom I remember the cele brated Dugald Stewart. Of course we youngsters sat silent, looked and listened . . . I remember . . . his shedding tears over a print representing a soldier lying dead in the snow, his dog sitting in misery on one side, on the other his widow with a child in her arms. His person was robust, his manners rustic, not clownish. . . . His countenance was more massive than it looks in any of the portraits. There was a strong expression of shrewdness in his lineaments ; the eye alone indicated the poetic character and temperament. It was large and of a dark cast, and literally glowed when he spoke with feeling or interest. I never saw such another eye in a human head. His conversation ex pressed perfect self-confidence, without the least intrusive f or wardness. . . . He was much caressed in Edinburgh, but the efforts made for his relief were extremely trifling." Burns went from those meetings, where he had been posing professors (no hard task), and turning the heads of duchesses, to share a bed in the garret of a writer's apprentice—they paid together 3s. a week for the room. It was in the house of Mr. Carfrae, Baxter's Close, Lawnmarket, "first scale stair on the left hand in going down, first door in the stair." During Burns's life it was re served for William Pitt to recognize his place as a great poet ; the more cautious critics of the north were satisfied to endorse him as a rustic prodigy, and brought upon themselves a share of his satire. Some of the friendships contracted during this period— as for Lord Glencairn and Mrs. Dunlop—are among the most pleasing and permanent in literature. But in the poet's city life there was an unnatural element. He stooped to beg for neither smiles nor favour, but the gnarled country oak is cut up into cabinets in artificial prose and verse. In the letters to Graham, the prologue to Wood, and the epistles to Clarinda, he is dancing minuets with hob-nailed shoes. When, in 1787, the second edition of the Poems came out, the proceeds of their sale realized for the author 1400. On the strength of this sum he gave himself two long rambles, full of poetic material—one through border towns into England as far as Newcastle, returning by Dumfries to Mauchline, and another a grand tour through the East Highlands, as far as Inverness, returning by Edinburgh, and so home to Ayrshire.

In 1788 Burns took a new farm at Ellislandl on the Nith, settled there, married, lost his little money, and wrote, among other pieces, "Auld Lang Syne" and "Tam o' Shanter." In 1789 he obtained, through the good office of Mr. Graham, of Fintry, an appointment as excise-officer of the district, worth 150 per annum. In 1791 he removed to a similar post at Dumfries worth 170. In the course of the following year he was asked to con tribute to George Thomson's Select Collection of Original Scot tish Airs with Symphonies and Accompaniments for the Piano forte and Violin: the poetry by Robert Burns. To this work he contributed about loo songs, the best of which are now ringing in the ear of every Scotsman from New Zealand to San Fran cisco. For these, original and adapted, he received a shawl for his wife, a picture by David Allan representing the "Cotter's Saturday Night" and 15. The poet wrote an indignant letter and never afterwards composed for money. Unfortunately the "Rock of Independence" to which he proudly retired was but a castle of air, over which the meteors of French political enthusiasm cast a lurid gleam. In the last years of his life, exiled from polite society on account of his revolutionary opinions, he became sourer in temper and plunged more deeply into the dissipations of the lower ranks, among whom he found his only companion ship and sole, though shallow, sympathy.

'In 1928 Ellisland was bequeathed to the British nation by John Williamson of Edinburgh.

Burns began to feel himself prematurely old. Walking with a friend who proposed to him to join a county ball, he shook his head, saying "that's all over now," and adding a verse of Lady Grizel Baillie's ballad 0 were we young as we ance hae been, We sud hae been galloping down on yon green, And linking it ower the lily-white lea, But were na my heart light I wad dee.

His hand shook ; his pulse and appetite failed ; his spirits sank into a uniform gloom. In April 1796 he wrote—"I fear it will be some time before I tune my lyre again. By Babel's streams I have sat and wept. I have only known existence by the pressure of sickness and counted time by the repercussions of pain. I close my eyes in misery and open them without hope. I look on the vernal day and say with poor Fergusson Say wherefore has an all-indulgent heaven Life to the comfortless and wretched given." On July 4 he was seen to be dying. On the 12th he wrote to his cousin for the loan of f i o to save him from passing his last days in jail. On the 21st he was no more. On the 25th, when his last son came into the world, he was buried with local honours, the volunteers of the company to which he belonged firing three volleys over his grave.

Burns's lyrics owe part of their popularity to the fact of their being an epitome of melodies, moods and memories that had be longed for centuries to the national life, the best inspirations of which have passed into them. But in gathering from his ancestors Burns has exalted their work by asserting a new dignity for their simplest themes. He is the pupil of Ramsay, but he leaves his master to make a social protest and to lead a literary revolt. The Gentle Shepherd, still largely a court pastoral, in which "a man's a man" if born a gentleman, may be contrasted with "The Jolly Beggars"—the one is like a minuet of the ladies of Ver sailles on the sward of the Swiss village near the Trianon, the other like the march of the maenads with Theroigne Me1i court. Ramsay adds to the rough tunes and words of the ballads the refinement of the wits who in the "Easy" and "Johnstone" clubs talked over their cups of Prior and Pope, Addison and Gay. Burns inspires them with a fervour that thrills the most wooden of his race. We may clench the contrast by a representative ex ample. This is from Ramsay's version of perhaps the best-known of Scottish songs : Methinks around us on each bough A thousand Cupids play ; Whilst through the groves I walk with you, Each object makes me gay.

Since your return—the sun and moon With brighter beams do shine, Streams murmur soft notes while they run As they did lang syne.

Compare the verses in Burns— We twa hae run about the braes And pu'd the gowans fine ; But we've wandered mony a weary foot Sin auld lang syne.

We twa hae paidl'd in the burn, Frae morning sun till dine: But seas between us braid hae roar'd Sin auld lang syne.

The affectations of Burns's style are insignificant and rare. His prevailing characteristic is an absolute sincerity. A love for the lower forms of social life was his besetting sin ; Nature was his healing power. He compares himself to an Aeolian harp, strung to every wind of heaven. His genius flows over all living and lifeless things with a sympathy that finds nothing mean or insig nificant. An uprooted daisy becomes in his pages an enduring emblem of the fate of artless maid and simple bard. He disturbs a mouse's nest and finds in the "tim'rous beastie" a fellow-mortal doomed like himself to "thole the winter's sleety dribble," and draws his oft-repeated moral. He walks abroad and, in a verse that glints with the light of its own rising sun before the fierce sarcasm of "The Holy Fair," describes the melodies of a "simmer Sunday morn." He loiters by Afton Water and "murmurs by the running brook a music sweeter than its own." He stands by a roofless tower, where "the howlet mourns in her dewy bower," and "sets the wild echoes flying," and adds to a perfect picture of the scene his famous vision of "Libertie." In a single stanza he concentrates the sentiment of many night thoughts— The wan moon is setting beyond the white wave, And Time is setting wi' me, O.

For other examples of the same graphic power we may refer to the course of his stream— Whiles ow'r a lien the burnie plays As through the glen it wimpled, or to "The Birks of Aberfeldy" or the "spate" in the dialogue of "The Brigs of Ayr." The poet is as much at home in the pres ence of this flood as by his "trottin' burn's meander." Familiar with all the seasons he represents the phases of a northern winter with a frequency characteristic of his clime and of his fortunes; her tempests become anthems in his verse, and the sounding woods "raise his thoughts to Him that walketh on the wings of the wind" ; full of pity for the shelterless poor, the "ourie cattle," the "silly sheep," and the "helpless birds," he yet reflects that the bitter blast is not "so unkind as man's ingratitude." This constant tendency to ascend above the fair or wild features of outward things, or to penetrate beneath them, to make them symbols, to endow them with a voice to speak for humanity, distinguishes Burns as a descriptive poet from the rest of his countrymen.

Lovers of rustic festivity may hold that the poet's greatest performance is his narrative of "Hallowe'en," which for easy vigour, fullness of rollicking life, blended truth and fancy, is un surpassed in its kind. Campbell, Wilson, Hazlitt, Montgomery, Burns himself, and the majority of his critics, have recorded their preference for "Tam o' Shanter," where the superstitious element that has played so great a part in the imaginative work of this part of Britain is brought more prominently forward. Few passages of description are finer than that of the roaring Doon and Alloway Kirk glimmering through the groaning trees; but the unique excellence of the piece consists in its variety, and a perfectly original combination of the terrible and the ludicrous. Like Goethe's Walpurgis Nacht, brought into closer contact with real life, it stretches from the drunken humours of Christopher Sly to a world of fantasies almost as brilliant as those of the Midsummer Night's Dream, half solemnized by the severer atmosphere of a sterner clime. The contrast between the lines "Kings may be blest," and those which follow, begin ning "But pleasures are like poppies spread," is typical of the perpetual antithesis of the author's thought and life, in which, at the back of every revelry, he sees the shadow of a warning hand, and reads on the wall the writing, Omnia mutantur. With equal or greater confidence other judges have pronounced Burns's masterpiece to be "The Jolly Beggars." Certainly no other single production so illustrates his power of exalting what is insignifi cant, glorifying what is mean, and elevating the lowest details by the force of his genius. "The form of the piece," says Carlyle, "is a mere cantata, the theme the half-drunken snatches of a joyous band of vagabonds, while the grey leaves are floating on the gusts of the wind in the autumn of the year. But the whole is compacted, refined and poured forth in one flood of liquid harmony. It is light, airy and soft of movement, yet sharp and precise in its details; every face is a portrait, and the whole a group in clear photography. The blanket of the night is drawn aside ; in full ruddy gleaming light these rough tatterdemalions are seen at their boisterous revel wringing from Fate another hour of wassail and good cheer." Over the whole is flung a half humorous, half-savage satire—aimed, like a two-edged sword, at the laws, and the lawbreakers, in the acme of which the grace less crew are raised above the level of ordinary gipsies, footpads and rogues, and are made to sit "on the hills like gods together, careless of mankind," and to launch their Titan thunders of re bellion against the world.

A fig for those by law protected; Liberty's a glorious feast; Courts for cowards were erected, Churches built to please the priest.

The most scathing of his Satires, under which head fall many of his minor and frequent passages in his major pieces, are di rected against the false pride of birth, and what he conceived to be the false pretences of religion. The apologue of "Death and Dr. Hornbook," "The Ordination," the song, "No churchman am I for to rail and to write," the "Address to the Unco Guid," "Holy Willie," and above all "The Holy Fair," with its savage caricature of an ignorant ranter of the time called Moodie, and others of like stamp, not unnaturally provoked offence. Burns had a firm faith in a Supreme Being, not as a vague mysterious Power, but as the Arbiter of human life. Amid the vicissitudes of his career he responds to the cotter's summons, "Let us wor ship God." An atheist's laugh's a poor exchange For Deity offended is the moral of all his verse, which treats seriously of religious matters. His prayers in rhyme give him a high place among secular psalmists.

Like Chaucer, Burns was a great moralist, though a rough one. In the "Epistle to a Young Friend," the shrewdest advice is blended with exhortations appealing to the highest motive, that which transcends the calculation of consequences, and bids us walk in the straight path from the feeling of personal honour, and "for the glorious privilege of being independent." Burns, like Dante, "loved well because he hated, hated wickedness that hinders loving," and this feeling, as in the lines—"Dweller in yon dungeon dark," sometimes breaks bounds; but his calmer moods are better represented by the well-known passages in the "Epistle to Davie," in which he preaches acquiescence in our lot, and a cheerful acceptance of our duties in the sphere where we are placed. This philosophie douce, never better sung by Horace, is the prevailing refrain of our author's Songs. These have passed into the air we breathe; they are so real that they seem things rather than words, or, nearer still, living beings. They have taken all hearts, because they are the breath of his own; not polished cadences, but utterances as direct as laughter or tears. Between the first of war songs, composed in a storm on a moor, and the pathos of "Mary in Heaven," he has made every chord in our northern life to vibrate. The distance from "Duncan Gray" to "Auld Lang Syne" is nearly as great as that from Falstaff to Ariel. There is the vehemence of battle, 'the wail of woe, the march of veterans "red-wat-shod," the smiles of meeting, the tears of parting friends, the gurgle of brown burns, the roar of the wind through pines, the rustle of barley rigs, the thunder on the hill—all Scotland in his verse. Let who will make her laws, Burns has made the songs, which her emigrants recall "by the long wash of Australasian seas," in which maidens are wooed, by which mothers lull their infants, which return "through open casements unto dying ears"—they are the links, the watch words, the masonic symbols of the Scots race. (J. N.) The greater part of Burns's verse was posthumously published, and, as he himself took no care to collect the scattered pieces of occasional verse, different editors have from time to time printed, as his, verses that must be regarded as spurious. Poems chiefly in the Scottish dialect, by Robert Burns (Kilmarnock, 1786), was followed by an enlarged edition printed in Edinburgh in the next year. Other editions of this book were printed—in London (1787) , an enlarged edition at Edinburgh (I793) and a reprint of this in 1794. A facsimile of the 1786 edition was published in 1927. Poems by Burns appeared originally in the Caledonian Mercury, the Edinburgh Evening Courant, the Edinburgh Herald, the Edinburgh Advertiser; the London papers, Stuart's Star and Evening Advertiser (subsequently known as the Morning Star), the Morning Chronicle; and in the Edinburgh Maga zine and the Scots Magazine. Many poems, most of which had first appeared elsewhere, were printed in a series of penny chapbooks, Poetry Original and Select (Brash and Reid, Glasgow), and some appeared separately as broadsides. A series of tracts issued by Stewart and Meikle (1796-99) includes some of Burns's numbers; The Jolly Beggars, Holy Willie's Prayer and other poems making their first appearance in this way. The seven numbers of this publication were reissued in Jan. i800 as The Poetical Miscellany. This was followed by Thomas Stewart's Poems ascribed to Robert Burns (Glasgow, 18oi). Burns's songs appeared chiefly in James Johnson's Scots Musical Museum (1787-1803) , which he appears after the first volume to have virtually edited, though the two last volumes were published only after his death ; and in George Thomson's Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs Only five of the songs done for Thomson appeared during the poet's lifetime, and Thomson's text cannot be regarded with confidence. The Hastie mss. in the British museum (Addit. ms. 22,307) include 162 songs, many of them in Burns's handwriting ; and the Dalhousie ms., at Brechin Castle, con tains Burns's correspondence with Thomson. For a full account of the songs see James C. Dick, The Songs of Robert Burns now first printed with the Melodies for which they were written (1903) ; also D. Cook, Annotations of Scottish Songs by Burns (1922) .

The items in W. Craibe Angus's Printed Works of Robert Burns (1899) number 930. Only the more important collected editions can be here noticed. Dr. Currie was the anonymous editor of the Works of Robert Burns; with an Account of his Life, and a Criticism on his Writings . . . (Liverpool, 1800) . This was undertaken for the benefit of Burns's family at the desire of his friends, Alexander Cunningham and John Syme. A second and amended edition appeared in 1801, and was followed by others, but Currie's text is neither accurate nor complete. Additional matter appeared in Reliques of Robert Burns . . . by R. H. Cromek (London, 18o8). In The Works of Robert Burns, With his Life, by Allan Cunningham (London, 1834) there are many additions and much biographical material. The Works of Robert Burns, edited by James Hogg and William Motherwell (1838 41) , contains a life of the poet by Hogg, and some useful notes by Motherwell, attempting to trace the sources of Burns's songs. The Correspondence between Burns and Clarinda was edited by W. C. M'Lehose (1843) . An improved text of the poems was provided in the second "Aldine Edition" of the Poetical Works (5839), for which Sir H. Nicolas, the editor, made use of many original mss. In the Life and Works of Robert Burns, ed. by Robert Chambers (1851-52; library edition, 1856-57 ; new edition, revised by William Wallace, 1896), the poet's works are given in chronological order, interwoven with letters and biography. Other well-known editions are those of George Gilfillan (185b) ; of Alexander Smith (Golden Treasury Series 1865) ; of P. Hately Waddell (Glasgow, 1867) ; an edition with Dr. Currie's memoir and an essay by Prof. Wilson ; of W. Scott Douglas (the Kilmarnock edition, 1876, and the "library" edition, 1877-79), and of Andrew Lang, assisted by W. A. Craigie (1896) . The complete correspondence between Burns and Mrs. Dunlop was printed by W. Wallace (1898) .

A critical edition of the Poetry of Robert Burns, which may be regarded as definitive, and is provided with full notes and variant readings, was prepared by W. E. Henley and T. F. Henderson (1896- 97; reprinted i901), and is generally known as the "Centenary Burns." In vol, iii. the extent of Burns's indebtedness to Scottish folk-song and his methods of adaptation are minutely discussed; vol. iv. contains an essay on "Robert Burns. Life, Genius, Achievement," by W. E. Henley.

The chief original authority for Burns's life is his own letters. The principal "lives" are to be found in the editions just mentioned. His biography has also been written by J. Gibson Lockhart (Life of Burns, 1828) ; for the "English Men of Letters" series in 1879 by Prof. J. Campbell Shairp ; and by Sir Leslie Stephen in the Dictionary of National Biography (vol. viii., 1886) . For the more important essays on Burns see Thomas Carlyle (Edinburgh Review, Dec. 1828) ; John Nichol (W. Scott Douglas's edition of Burns) ; R. L. Stevenson (Familiar Studies of Men and Books) ; Auguste Angellier (Robert Burns: La vie et les oeuvres 1893) ; Lord Rosebery (Robert Burns: Two Addresses in Edinburgh, 1896) ; J. Logie Robertson (in In Scot tish Fields, 1890, and Furth in Field, 1894) ; T. F. Henderson, Robert Burns (1904) ; A. Dakers, Robert Burns. His Life and Genius (1923) . There is a selected bibliography in chronological order in W. A. Craigie's Primer of Burns (1896).