Artificial Silk

SILK, ARTIFICIAL). The salts de rived from cupric oxide are gen erally white when anhydrous, but blue or green when hy drated.

Copper quadrantoxide, Cu,O, is an olive-green powder formed by mixing well-cooled solutions of copper sulphate and alkaline stannous chloride; the tritoxide, Cus0, is obtained when cupric oxide is heated to 1,5oo°-2,000° C. Both are of doubtful com position. Copper dioxide, CuO2H20, is obtained as a yellowish brown powder, by treating cupric hydrate with hydrogen per oxide. When moist, it decomposes at about 6° C, but when dry at about 18o° (L. Moser, 1907).

Cuprous Hydride.

Cuprous hydride, (CuH)„, was first ob tained by A. Wurtz in 1844, who treated a solution of copper sulphate with hypophosphorous acid, at a temperature not exceed ing 7o° C. According to E. J. Bartlett and W. H. Merrill, it decomposes when heated and gives cupric hydride, which is a strong reducing agent.

Halides.

Cuprous fluoride, CuF, is a ruby-red crystalline mass, formed by heating cuprous chloride in an atmosphere of hydrofluoric acid at I,IOO°–I,2oo° C. It is soluble in boiling hydrochloric acid, but it is not reprecipitated by water, as is the case with cuprous chloride. Cupric fluoride, is obtained by dissolving cupric oxide in hydrofluoric acid. The hydrated form is obtained as blue crystals, sparingly soluble in cold water.Cuprous chloride, CuCl or was obtained by Robert Boyle by heating copper with mercuric chloride. It is also ob tained by burning the metal in chlorine, by heating copper and cupric oxide with hydrochloric acid, or copper and cupric chloride with hydrochloric acid. It dissolves in the excess of acid, and is precipitated as a white crystalline powder on the addition of water. It melts at below red heat to a brown mass, and its vapour density at both red and white heat corresponds to the formula Its solution in hydrochloric acid readily absorbs carbon monoxide and acetylene; hence it finds application in gas analysis. Its solution in ammonia absorbs acetylene, with the precipitation of red cuprous acetylide, a very explosive compound. Cupric chloride, is obtained by burning copper in an excess of chlorine, or by heating the hydrated chloride, ob tained by dissolving the metal or cupric oxide in an excess of hydrochloric acid. It is a yellowish-brown deliquescent powder, which rapidly forms the green hydrated salt on ex posure. The oxychloride occurs in nature as the mineral ataca mite [Cu { It may be artificially prepared by heating salt with ammonium copper sulphate to Ioo°. "Bruns wick green," a light green pigment, is obtained from copper sul phate and bleaching powder.

Cuprous iodide, is obtained as a white powder by the direct union of its components or by mixing solutions of cuprous chloride in hydrochloric acid and potassium iodide; or, with liber ation of iodine, by adding potassium iodide to a cupric salt. Cupric iodide is only known in combination, as in which is obtained by exposing to moist air, or in combination with ethylenediamine as Sulphides and Sulphate.—Cuprous sulphide, occurs in nature as the mineral chalcocite (q.v.) or copper-glance, and may be obtained as a black brittle mass by the direct combination of its constituents. Cupric sulphide, CuS, occurs in nature as the mineral covellite. It may be prepared by heating cuprous sulphide with sulphur, or as a dark brown precipitate by treating a copper solution with sulphuretted hydrogen. A cuproso-cupric sulphite, is obtained by mixing solutions of cupric sulphate and acid sodium sulphite.

Cupric sulphate or "blue vitriol," one of the most im portant salts of copper, occurs in cupriferous mine waters and as the minerals chalcanthite or cyanosite, and boothite, Cupric sulphate is obtained commercially by the oxidation of sulphuretted copper ores, or by dissolving cupric oxide in dilute sulphuric acid. It was obtained in 1644 by Van Helmont, who copper with sulphur and moistened the residue, and in 1648 by Glauber, who dissolved copper in strong sulphuric acid. It crystallizes with five molecules of water in large blue triclinic prisms. When heated to Ioo° C it loses four molecules of water and forms the bluish-white monohydrate, which, on further heating to 250°-26o°, is converted into the white The anhydrous salt is very hygroscopic, and hence finds application as a desiccating agent. It also absorbs gaseous hydrochloric acid. Copper sulphate is readily soluble in water, but insoluble in alcohol; it dissolves in hydrochloric acid with a considerable fall in temperature, cupric chloride being formed. The copper is readily replaced by iron, a knife-blade placed in an aqueous solution being covered immediately with a bright red deposit of copper. This was formerly regarded as a transmuta tion of iron into copper. Copper sulphate finds application in calico printing and in the preparation of the pigment Scheele's green.

Carbonates.

Normal cupric carbonate, has only been obtained in the form of such complex salts as (Reynolds, 1898) and (Morgan and Burstall, 1927), basic hydrated forms being formed when an alkaline carbonate is added to a cupric salt. Basic copper carbon ates are of wide occurrence in the mineral kingdom, and consti tute the valuable ores malachite, azurite and mountain or mineral green. Copper rust has the same composition as malachite; it results from the action of carbon dioxide and water on the metal. Basic copper carbonate is also the basis of the valuable blue to green pigments, verditer, Bremen blue and Bremen green.

Other Compounds.

.A copper nitride, is obtained by heating precipitated cuprous oxide in ammonia gas (A. Guntz and H. Bassett, 1906). A maroon-coloured powder, of composition is formed when pure dry nitrogen dioxide is passed over finely-divided copper at 25°-30°. It decomposes when heated to 9o° ; with water it gives nitric oxide and cupric nitrate and nitrite. Cupric nitrate, is obtained by dissolving the metal or oxide in nitric acid. It forms dark blue prismatic crys tals containing 3, 4 or 6 molecules of water according to the temperature of crystallization.Copper combines directly with phosphorus to form several compounds. The phosphide obtained by heating cupric phos phate, in hydrogen, when mixed with potassium and cuprous sulphides or levigated coke, constitutes "Abel's fuse," which is used as a primer. Basic copper phosphates occur fre quently in the mineral kingdom :—libethenite, ; chalcosiderite, a basic copper iron phosphate; torbernite, a copper uranyl phosphate ; andrewsite, a hydrated copper iron phosphate ; and henwoodite, a hydrated copper aluminium phosphate.

Copper forms several arsenides occurring in the mineral king dom :—whitneyite, algodonite, Cu,As, and domeykite, Copper arsenate is similar to cupric phosphate, and the resemblance is to be observed in the naturally occurring copper arsenates, which are generally isomorphous with the corresponding phosphates. Copper arsenite forms the basis of a number of once valuable, but very poisonous, pigments. Scheele's green is a basic copper arsenite ; Schweinfurt green, an aceto-arsenite ; and Casselmann's green a compound of cupric sulphate with potassium or sodium acetate.

Copper silicates occur in the mineral kingdom, many minerals owing their colour to the presence of a cupriferous element. Dioptase (q.v.) and chrysocolla (q.v.) are the most important forms.

Detection.—Compounds of copper impart a bright green coloration to the flame of a Bunsen burner. Ammonia gives a characteristic blue coloration when added to a solution of a copper salt ; potassium ferrocyanide gives a brown precipitate, and, if the solution be very dilute, a brown colour is produced. This latter reaction will detect one part of copper in 500,000 of water. For the borax beads and the qualitative separation of copper from other metals (see CHEMISTRY: Analytical). For the quantitative estimation (see ASSAYING : Copper) .

Medicine.

In medicine copper sulphate is employed occa sionally as a rapid emetic, but its employment is very rare, as it is exceedingly depressant and, if it fails to act, may seriously damage the gastric mucous membrane. It is, however, a useful superficial caustic and antiseptic. A colloidal copper lysalbumin ate has been used tentatively in malignant disease. All copper compounds are poisonous.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.--J. W. Mellor,

A Comprehensive Treatise on InBibliography.--J. W. Mellor, A Comprehensive Treatise on In- organic and Theoretical Chemistry, vol. iii. (1923) ; J. Newton Friend, A Text-book of Inorganic Chemistry, vol. H. (1924) ; Gmelin-Kraut, Handbuch der Anorganischen Chemie, vol. v. pt. I. (Heidelberg, 19o9) ; R. Abegg, Handbuch der Anorganischen Chemie, vol. ii., pt. I. (Leipzig, 19o8). (X.; G. T. M.) Copper was probably the first metal to be utilized by mankind, apart from gold and silver which were, no doubt, employed chiefly for ornamental purposes. In the native state, as metal, it is found in various parts of the world, and from these sources the first supplies are presumed to have been obtained, the metal in this state being malleable and requiring no metallurgical treatment prior to use. At some later date the more readily reducible oxide ores were treated by primitive peoples, ample evidence of this being obtained from time to time as new copper deposits are dis covered and prehistoric workings are revealed. The extraction of the metal from the sulphide ores presented more difficulty than from the simpler oxide ores ; in some districts the sulphides appear to have resisted satisfactory treatment, and were therefore neglected.The development of the extraction processes until the middle ages was very gradual, and was confined mainly to obtaining greater recovery of metal from a given quantity of ore. By that time, however, the general principles which underlie the methods for the dry extraction of copper were appreciated, and they may be stated as follows. Since all sulphuretted copper ores (and these are of chief economic importance) are invariably contaminated with arsenic and antimony, it is necessary to eliminate these im purities as far as practicable at the earliest possible stage in the treatment. This is effected by calcination or roasting.

The roasted ore is then smelted to a mixture of copper and iron sulphides, known as "copper matte" or "coarse-metal," which con tains little arsenic, antimony or silica. This coarse-metal is smelted with coke and siliceous fluxes (in order to slag away the iron) and the product, consisting of an impure copper sulphide, is variously known as "blue-metal" when more or less iron is still present, "pimple-metal" when richer in copper, or "fine" or "white-metal" which is a matte consisting of comparatively pure copper sulphide and containing approximately 75% of the metal. This product is re-smelted to form "coarse copper" or "blister copper" containing 95-97% of the metal, which is then refined.

Refining.

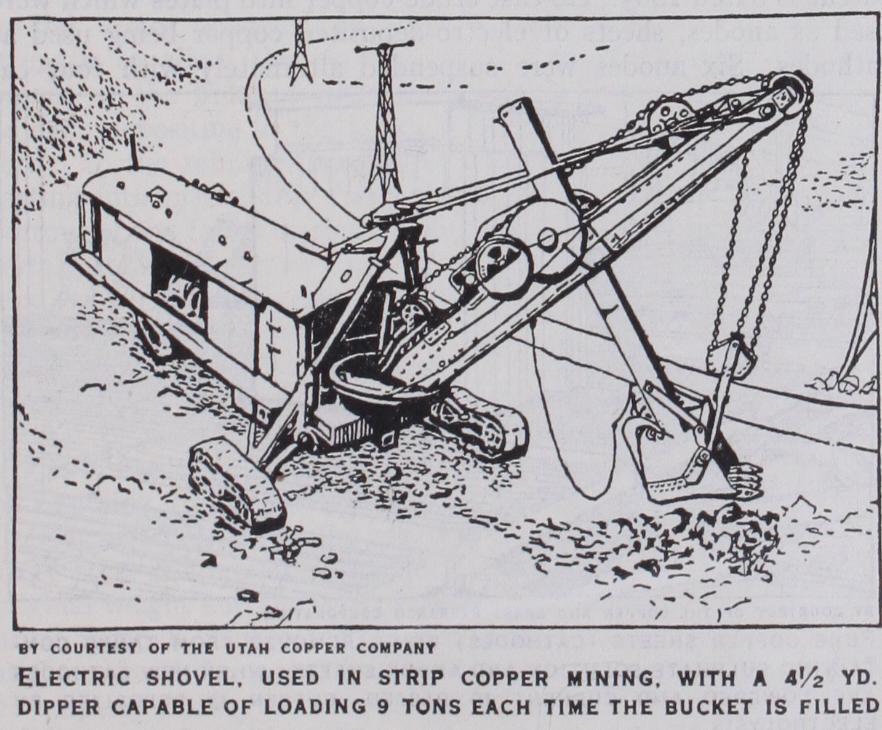

Blister or coarse copper contains numerous impuri ties. Sulphur, iron, lead, arsenic and antimony are almost in variably present. Silenium, tellurium, zinc, nickel and cobalt are also liable to occur, and in addition, silver and gold, which are frequently found in sufficient quantity to pay for their extrac tion. The object of refining is to remove these impurities as far as possible and to cast the copper into cakes and other forms suitable for mechanical treatment and conversion into rods, sheets, tubes, etc. The elimination of the impurities is effected by oxidation and removal either as slag or by volatilization. During the process the molten metal itself becomes partly oxidized, and this oxida tion is continued and aided by the agitation of the bath with iron rabbles, or in more modern plants by means of compressed air blown either on the surface of the bath or below it. This opera tion is termed "flapping" and is continued until the metal con tains approximately 6% of cuprous oxide. The iron, sulphur, zinc, tin and cobalt will have been almost completely eliminated. Ar senic, nickel and some other metals are not so completely removed, whilst the gold and silver and rarer metals still remain in the bath of metal. A sample ingot taken at this stage and allowed to solid ify, contracts on solidification and exhibits a brick red surface when fractured.The metal in this condition is known as "sett copper," and is relatively hard and easily fractured owing to the presence of the cuprous oxide. It is therefore necessary to reduce this oxide and reconvert it into metal. This is effected by "poling," which con sists in forcing green trees or logs under the surface of the molten metal. The products which are evolved from the combustion and distillation of the wood reduce the oxide to metal, and if the operation be properly conducted, "touch-pitch" copper, soft, mal leable and exhibiting a lustrous, silky fracture, is obtained. The progress of the reduction is checked from time to time by the re moval of small test buttons which are hammered out hot, quenched and fractured. Fracture must only occur when the but ton is completely doubled over and flattened, and should show a silky texture and be of a salmon pink colour. Considerable skill is needed at this stage of refining, as if the poling be carried too far the metal again becomes brittle and porous owing to the absorp tion of furnace gases. Such metal is termed "over-poled," and on solidification the top surface of the ingot rises owing to the liber ation of the absorbed gases during solidification. When the oper ation is carried out correctly, the castings solidify with a flat rip pled surface but this appearance although essential to good "touch pitch" copper is only indicative of good material when the furnace condition as regards temperature and atmosphere are known to have been satisfactory.

The "touch-pitch" condition is closely associated with the oxy gen remaining in the metal and this is, in turn, influenced by a variety of factors, including the furnace conditions and tempera ture in addition to the collective effect of the various impurities present in the metal. Modern refining practice gives very close attention to all these factors and the larger furnaces and mechani cal devices enable very close control of the oxygen content to be maintained.

The processes so far described are those developed to deal with a diversity of ore mixtures which were obtained from various sources and were treated on a relatively small scale both in Wales and in Germany. This position changed with the development of the enormous American ore bodies of comparatively uniform com position, whilst in addition, an immensely greater scale of opera tions was rendered possible by the increasing quantities of the metal required for the various forms of electrical development.

Towards the end of the i 9th century, America rose very rapidly to be the world's greatest producer of copper, and in 1926 the United States produced 789,00o metric tons or over one-half of the world's total output. The fact that 86% of the total was produced by 35 companies shows the scale of the operations that have been in use.

The treatment methods have been continually modified to take full advantage of all modern metallurgical improvements, the di rect result of which has been considerable simplification of the extraction process. In principle the operations are similar to those already described, and may be classified under three main head ings :—(i) concentration, (2) furnace treatment, (3) electrolytic refining. In addition, some ores and residues are now treated by hydro-metallurgical extraction methods or leaching followed by electrolytic deposition.

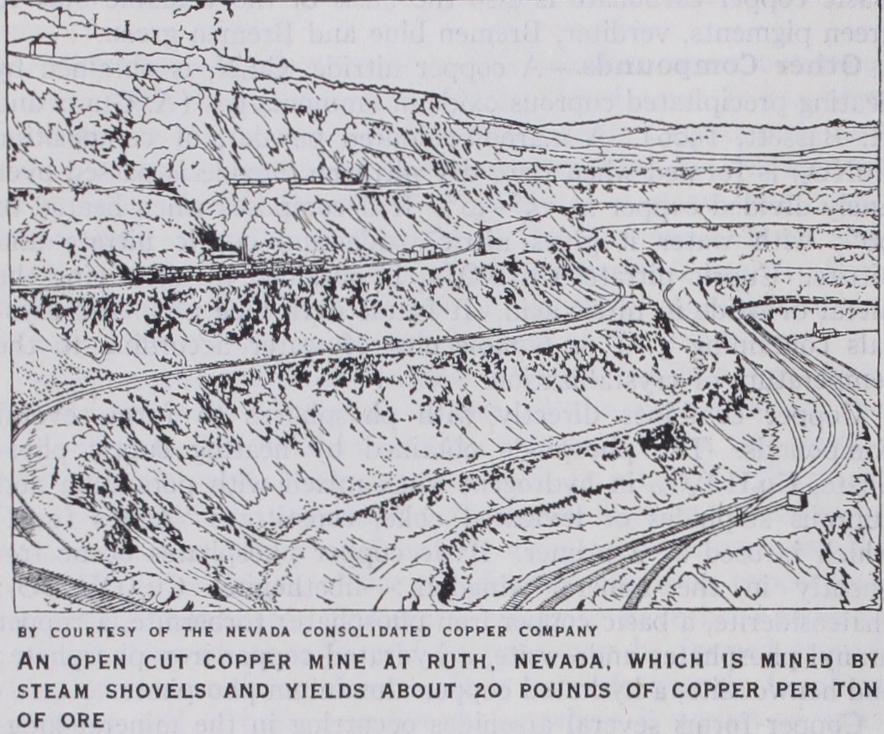

Concentration.—Apart from the general development of or dinary crushing and dressing plant practice, the outstanding fea ture is the use of the oil flotation process and the high recoveries obtained from this method. Selective flotation is now applied to copper sulphide-pyrites ores so that there is an elimination of both silica and iron, leaving a high grade copper concentrate for smelt ing. In the case of mixed oxidized and sulphide ores it is still a question whether the oxide portion can be floated with the sul phide, although success is claimed by the use of potassium xan thanate. These improvements in dressing practice are permitting very poor ore bodies to be mined economically; for example, in 1926 the Miami Copper Company were working at a profit an ore body containing but 20 lb. copper per ton. Differential flotation is being applied on various plants, including Anaconda, and results in a much greater ratio of concentration which permits the smaller tonnage of richer concentrates obtained to be treated in reverberatory furnaces.

Furnace Treatment.

Prior to 1910 the blast furnace and the reverberatory furnace were in close competition for. the ascendancy in the smelting of copper ore. With the increasing fineness of the ore to be smelted, resulting from the fine crushing necessary to obtain satisfactory recoveries from the poorer ores treated by the dressing plant, the leaning began to be definitely in favour of the reverberatory furnace. But with the advent of the Dwight-Lloyd and other sintering plants, which enabled fine ores to be agglomerated cheaply and efficiently, the blast furnace gained a new prestige. The recent developments of selective flota tion enabling higher grade concentrates to be obtained, combined with the successful application of coal dust firing to reverbera tory furnaces have again given this type of furnace an unques tioned predominance which it is likely to maintain. The modern copper smelting plant designed for the treatment of fine ore com prises roasting furnaces of the McDougall type and very large re verberatory furnaces. The process of extraction consists of (a) roasting in mechanical furnaces, (b) smelting to matte in rever beratory furnaces, (c) blowing the matte to blister in basic con verters, (d) casting the blister into anodes either direct or after partial refining in reverberatory furnaces, and (e) electrolytic refining.

Roasting.

The McDougall type furnace is essentially a verti cal cylinder with superimposed horizontal hearths and a central rotating shaft with radial arms for stirring the ore. The ore is fed in mechanically at the top of the furnace and is displaced by the rabble arms towards the periphery when it drops to the hearth beneath. The rabbles are here arranged to move the ore in the opposite direction, succeeding hearths being arranged alternately with slots provided for the ore to drop from one hearth to the next beneath. The central shaft and arms, water cooled in the original design, are now pressure air cooled as this offers several advantages, amongst which may be cited the absence of scaling and the possi bility of returning the heated air to the bottom of the furnace for combustion purposes. Various other types of mechanical roasting furnaces were at one time used for copper ores but they have all been superseded by one of the several modifications of the Mc Dougall furnace, variously known as Evans-Klepetko, Herreshoff or Wedge furnace. The modern practice is to treat this calcine or roasted material in reverberatory furnaces, which have been con tinuously increasing in size, although they now appear to have reached their maximum as regards length. The tendency in most recent construction is to make them approximately molt. in length and to increase the width, although constructional diffi culties have hampered this development and few exceed 25ft. in width. All these modern furnaces use either pulverized coal or oil as a fuel, the choice depending on economic factors, great economy being effected by passing the flue gases through waste heat boilers to recover rather more than a third of the heating value of the fuel in the form of steam. The charging of the hot calcines is carried out along the sides of the furnace at frequent intervals, and this practice combined with the addition of highly siliceous ore for fettling purposes preserves the furnace sides. The furnace has two distinct functions, the first being the smelting of the charge, and the second the settling of the matte produced. The matte usually contains approximately 40% copper and is with drawn intermittently as required for further treatment. The slag is withdrawn continuously from the far end of the furnace and flows into slag cars or granulating troughs. Such slags contain rather more copper than blast-furnace slag, and this is probably accounted for by dusting during the charging of such fine ma terial. Special precautions are taken to collect the flue dust which is returned for further treatment. The next operation consists in the elimination of the sulphur from the matte and the produc tion of blister copper in one operation.

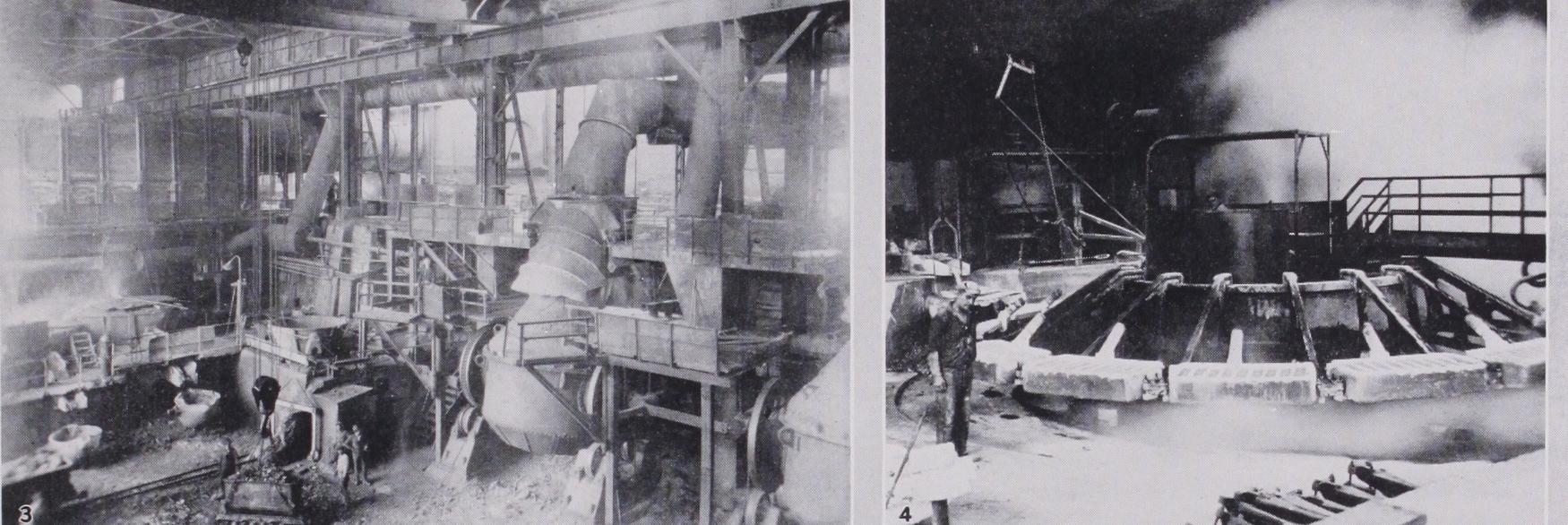

Converting.

The converting process consists in blowing thin streams of air under pressure through the molten matte retained in a suitable container. It was first used for copper by Manhes and David in France, and at a later date the process was intro duced both at Butte, Montana, and in Wales. Originally the con verters were lined with siliceous material, the lining furnishing the silica required to flux the iron oxide produced during the blowing. Numerous attempts were made to replace this lining by a basic lining owing to the short life of the acid linings, but not until 1910 was success achieved by Pierce and Smith in America. Sub sequently it was found that the basic lining was not limited in its application to the horizontal converters originally used, but could be applied to other forms of both the horizontal and vertical types. Amongst the advantages of the basic lined converter, as compared with the acid lined type, are an increased life of the lin ing (one basic lining produces 2,500 tons copper as compared with ten tons from an acid lining), greater air efficiency, and abil ity to convert low grade matte. Modern basic lined converters are lined with magnesite, and the Pierce-Smith type, which is gen erally favoured, consists of a horizontal cylindrical shell of steel plate supported on cast steel rings, which can revolve on rollers. The converters are of varying dimensions, to meet the operating conditions in various plants. An ordinary large size converter measures 13 f t. x 3oft. and the air is supplied through 41 1 yin. tuyeres spaced at 61in. centres. In order to utilize the sulphur ous gases for acid manufacture or special arrangements are made in the form of hoods to prevent dilution with air. In con verting 40% matte to blister copper, the daily capacity of such a converter varies from 110-125 tons. The method of operation is to charge in liquid matte and siliceous ore in given proportions and blow for 3o to 4o minutes. The slag formed is then poured off, and further additions of liquid matte, siliceous ore together with converter cleanings and cold matte, are added and help to lower the temperature of the bath. The charge is again blown, and the operation repeated until the converter is fully charged and the matte is enriched to "white-metal" (70-75% copper) . The slag is then cleaned off as thoroughly as possible, scrap copper, cold white metal, etc., are added to reduce the temperature, and the final blow to blister copper is made. This blister copper is frequently tapped into ladles and transferred molten to reverberatory furnaces for partial refining and conversion into anodes for treatment in the electrolytic refining. In some instances the anodes are cast direct from the converter, and although in such cases, owing to their uneven thickness, the electrolytic treatment is less efficient, the expense saved by eliminating the reverberatory treatment may balance the smaller recovery. In preparing anodes in the rever beratory refining furnace the same care need not be taken as for finished copper, and it is usual to leave a larger proportion of cuprous oxide in the metal. The furnace can be of large capacity, and casting is carried out by means of a mechanical casting ma chine, the anodes passing to the electrolytic refining. The pro cedure described is applicable to fine ores such as sulphide concen trates, but for the smelting of coarse ore the blast-furnace op erated on a pyritic or semi-pyritic principle still holds its place.

Pyritic Smelting.

In this process the oxidation of pyritic ores and the formation of the slag furnish the heat necessary to carry on the operation. Partial pyritic smelting is one in which the deficiency of sulphur in the charge is made up by the addition of some carbonaceous fuel. In both cases considerably more air is required than when carbon forms the fuel. This pyritic effect is utilized in some degree in practically all blast furnace practice and the modern blast furnaces have been designed to meet these re quirements. They are oblong in shape, with vertical ends and sloping sides fitted with the necessary tuyeres. The discharge is continuous, the slag matte mixture running continuously over a raised spout trapping the blast. The matte and slag collect in a large fore-hearth settler where the matte settles and is tapped periodically for feeding to the converters. The slag is run off con tinuously, either into a slag car or into some granulating device. The large furnaces at Anaconda are 87ft. long by 56in. wide at the tuyeres. Increasing the length in this manner decreases the heat losses at the ends, giving greater regularity in operation with lower fuel and labour costs. In cases when a low grade matte is produced this is enriched sufficiently for converting by a second smelting, and is transferred molten or re-melted if the conditions are not favourable for immediate treatment.

Hydro-metallurgical Treatment.

The development of this type of treatment has received considerable attention in certain cases where it is particularly applicable. It is eminently suited for low grade ores and residues with finely disseminated copper min eral and a gangue that is not attacked by the solvent. Leaching may be divided into three classes :—( ) leaching in place, (2) heap leaching, (3) confined leaching in vats, tanks or other vessels. The first is only applicable when the mineral in the natural 'state is in a form soluble in the solvent, with the gangue in such a con dition that the solution can operate. It is in successful operation at the Ohio Copper Co.'s mine, Utah, where the rock is shattered, leaving the mineral exposed along cleavage planes. Water intro duced on the surface emerges in the main haulage tunnel with little loss. The ore ranges between o.3% and 1.3% copper, and natural ventilation aids oxidation and renders the mineral readily soluble. The copper in the solution pumped out is precipitated on de-tinned scrap, yielding a 9o% copper precipitate, whilst one-third of the de-coppered liquor with two-thirds fresh water is returned to the mine.Heap leaching was first practised at Rio Tinto, Spain, and is in successful operation there and at other mines in Spain and Portu gal. At Rio Tinto weathering is used to render the mineral soluble, the ore being a sulphide mineral which is crushed and sorted into coarse and fine. The heaps are of large dimensions, and are made up of alternate layers of coarse and fines, the top layers consisting of fine ores to assist the distribution of the water. Whilst the heap is in course of formation, water is added to dissolve any cop per sulphate already existent, and to hasten oxidation. The top of the heap is divided up with ridges for the even distribution of the water and the temperature during wddation is adjusted by ma nipulating the outlets from the stacks which are built up through the heap. It is essential for the oxidation to be regular and gradual to produce the desired porous material suitable for wet extraction. When the heap is sufficiently oxidized, water and liquor from the depositing tanks are run on until the soluble copper has been ex tracted. At intervals of approximately one year the water dis tributing channels are changed in position, and it takes six to seven years with massive ore to reduce the heap of approximately oo,000 tons to o.25–o.3o% copper, which is the economic limit of extraction. The liquor obtained is first reduced by contact with freshly mined pyritic fines, and the copper is then precipitated with pig-iron in the usual manner.

Confined leaching in vats is the most general method of leaching in Chile. Thus at Chuquicamata a deposit of approximately 7o9,000 tons assaying 2% copper is being treated by such methods. The copper occurs in the ore as brochantite contaminated with chlorides. The process consists in crushing 9o% of the mineral to pass a iin. sieve, leaching with sulphuric acid, purification of the solution and deposition of the copper by electrolysis, using ferro silicon anodes. The copper cathodes produced are cast into bars equal in grade to standard electrolytically refined copper.

Ammonia leaching has not found very general acceptance, but in one or two instances, under special conditions, it has been suc cessfully instituted. Low grade carbonate ores and native copper tailings yield readily to this treatment, and successful plants are in operation in Alaska and at the Calumet and Hecla property, Michigan. At the latter plant, tailings from concentrating native copper are being treated, the solution used containing 3% copper, 6% NH, and 4% CO,. The copper content of the solution is regu lated by withdrawals for precipitation whilst losses of ammonia and CO, are replaced. In order to maintain the solution in an oxidized condition, it is circulated through towers with an upward air current, any ammonia passing away during this treatment being recovered in absorption towers. The copper is precipitated from the ammoniacal solutions by boiling in special evaporators and the ammonia is recovered. A further development of ammonia leaching is being applied in Africa at Bwana M'Kubwa. A proces§ has been developed for obtaining satisfactory recoveries from sili cate ores (such as chrysocolla) which have previously presented many difficulties. The ore is first crushed to about lin. to 'in. and is then fed to a preheater, which is a cylindrical furnace of the rotary kiln type, where it is heated to 400–soo° C. for about 3o minutes. The furnace de-hydrates the ore and heats it to the neces sary temperature for a reaction to occur in the next furnace, to which it is transferred. The second furnace is maintained with a reducing atmosphere by a stream of producer gas, the heat of the reaction being sufficient to maintain the temperature. The reduc tion takes place rapidly, but the furnace has to be arranged with water cooling at the exit, so that the ore may be cooled down before passing into the air. The reduced ore is then crushed in rolls to the size necessary for successful extraction by leaching. The copper content of the ore is now readily soluble in ammonium carbonate in the presence of oxygen, and the usual methods are employed for the subsequent precipitation of the copper in the form of oxide. Tar and ammonia are both by-products in the manufacture of the producer gas required for the process. The tar is utilized by mixing with the oxide produced and aids reduction during the final refining, whilst the ammonia is stated to be sufficient in quantity to make up the losses during leaching.

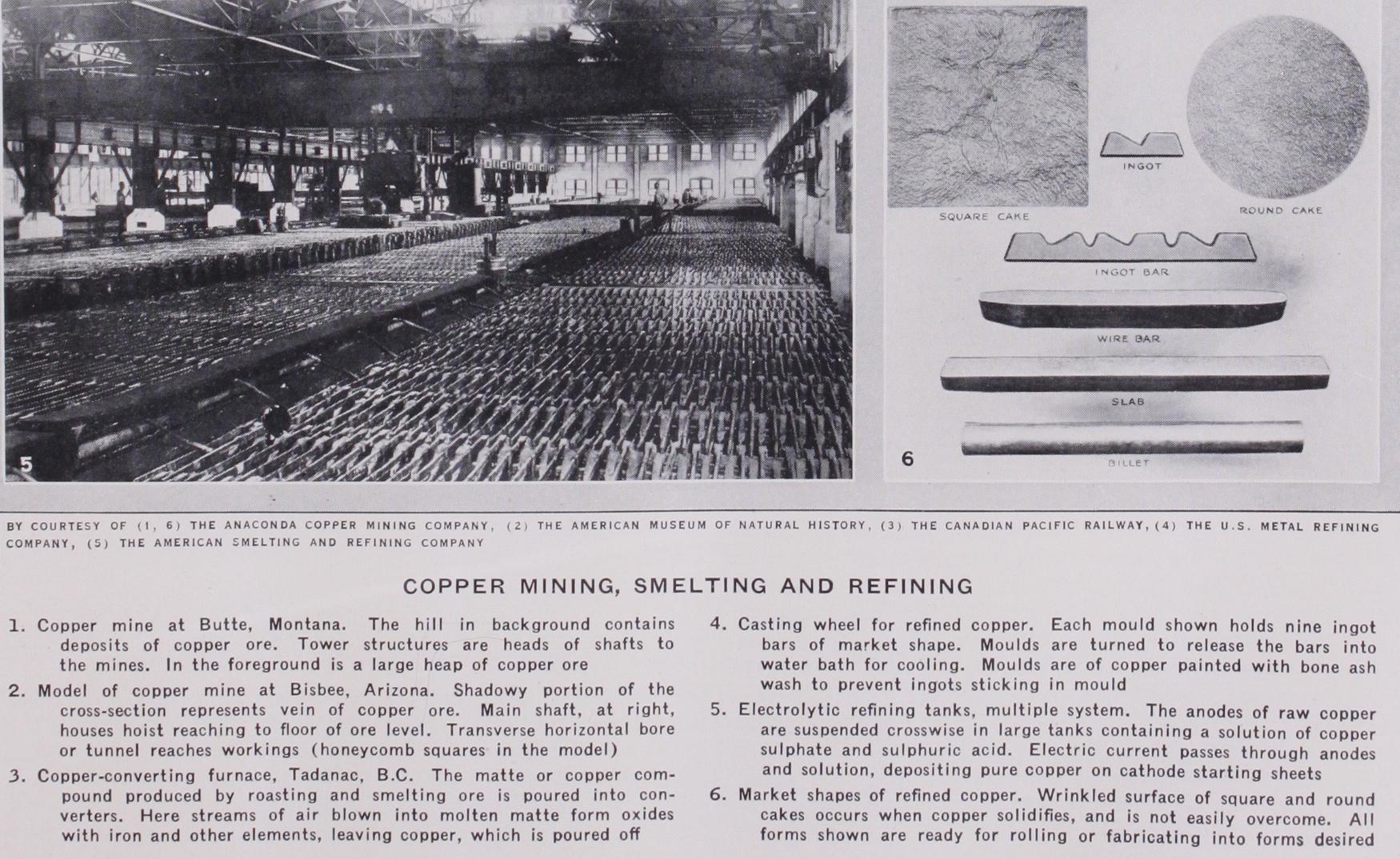

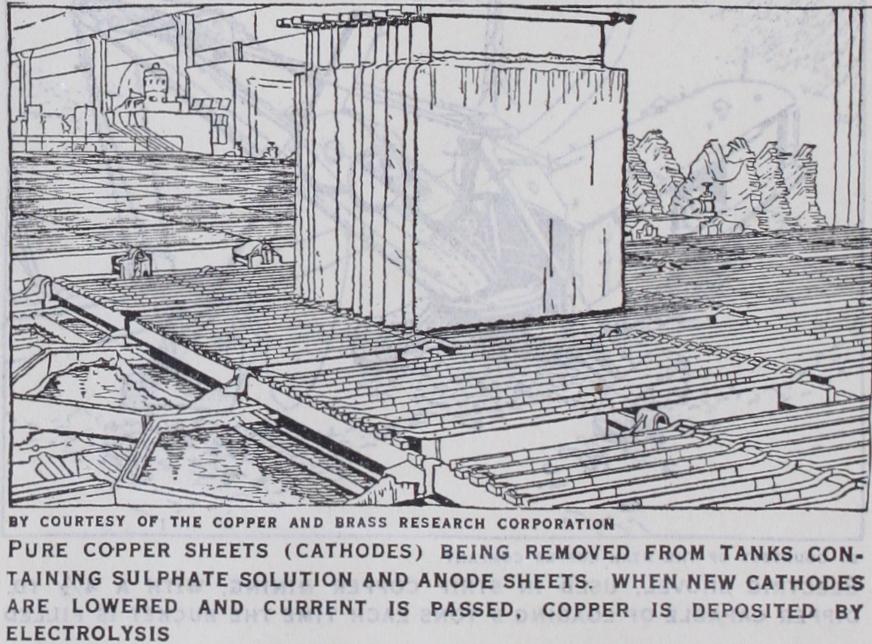

Electrolytic Refining.

Copper made by this process con tains a negligible quantity of impurities, and constitutes by far the greater portion of the world's production. The earliest attempt to refine copper electrolytically was made by Elkington, whose first patent is dated 1865. He cast crude copper into plates which were used as anodes, sheets of electro-deposited copper being used as cathodes. Six anodes were suspended alternately with four ca thodes in a saturated solution of copper sulphate in a fireclay trough all the anodes being connected in one parallel group and all the cathodes in another. A hundred or more troughs were coupled in series, the cathodes of the one to the anodes of the next, and they were so arranged that, with the aid of side pipes with leaden connections and India rubber joints, the electrolyte could be made to circulate once daily through them all from the top of one jar to the bottom of the next. The passage of current was con tinued until the anodes were of no further use and the cathodes, when thick enough, were removed and either cast into cakes and rolled or disposed of as cathodes. Silver, gold and other insoluble impurities collected at the bottom of the tanks up to the level of the lower side tubes and were then run off as mud through plugs or holes in the bottom, and collected in settling tanks for further treatment. Elkington's method is now known as the multiple sys tem; a second method of connecting up the tanks, known as the series system, being introduced in 1886. America produces the greater part of the electrolytic copper required and over 8o% of this copper output is prepared in this manner. The efficiency of the process is dependent on the composition, character and tem perature of the electrolyte, the current density and the voltage, all of which have to be carefully controlled.

The Multiple System.—This is now worked in oblong tanks with anodes made from copper partially refined after converting, and cathodes of pure copper.

The usual composition of the electrolyte is 3o% copper and I 2 % free sulphuric acid. The temperature of the bath ranges from 4o to 6o° C and continuous circulation of the liquid is essential to correct variations in com position. The drop in potential between tanks ranges from 0.2 to 0.4 volts, and it was found at Anaconda that more than 2o% of the drop was due to contact resistance and leakages. The cur rent density in use ranges from 15 to 25 amperes per sq. ft., depending on the purity of the material to be treated and the power cost in relation to the increased output obtained. The anodes used should be as pure as possible, to avoid contamina tion of the electrolyte, and commonly average 99% copper, the precious metals recovered very largely defraying the cost of the process. In modern plants the anodes are usually cast about aft. square and may be up to i lin. in thickness. Mechanical arrange ments are provided for handling them in and out of the tanks in groups. The cathodes now used consist of thin sheets of deposited copper which are deposited on rolled sheet copper in special tanks arranged to form a slow deposit of sufficient strength to allow the starting sheet formed to carry the full weight of the finished cathode. These cathodes, after seven to 14 days depositing in the tanks, are rQmoved, washed and trans ferred to the refining-furnace for remelting, poling to pitch and casting into marketable forms. The slime which collects in the bottom of the tanks carries the impurities, and from time to time certain tanks are thrown out of circuit for the collection of the mud, which is then treated for the extraction of the rare metals.