Colloids

COLLOIDS. In a paper entitled "Liquid Diffusion applied to Analysis" published in 1861 in the Philosophical Transactions, Thomas Graham (q.v.) described the results of an investigation carried out with very simple means. Aqueous solutions were placed in a cylindrical vessel the bottom of which was formed by a piece of animal membrane, like pig's bladder, or by the recently invented parchment paper, and the membrane immersed in water. The amount of dissolved substance which diffused into the outer water was determined from time to time. Graham found that the numerous substances examined fell into two classes: those which diffused in appreciable amounts and those which hardly passed through the membrane in perceptible quan tities. The former were without exception substances known to crystallize from their solutions, like various salts or sugar, while the latter, among' which were albumin, gum arabic or gelatin, had never been known as crystals. Graham accordingly called the first class crystalloids and the second class colloids (from colla, glue).

Graham made the further discovery that a number of sub stances known to be insoluble in water could, by appropriate procedure, be brought into a state of solution. Thus prussian blue, the well-known pigment, is quite insoluble in water, but dissolves in a solution of oxalic acid. If such a solution is placed in Graham's apparatus, the oxalic acid diffuses into the outside water and the prussian blue remains behind, but still forms what appears a perfectly clear solution, and thus behaves like Graham's other colloids. He called this method of separating crystalloid from colloid constituents "dialysis" and the apparatus used for it a "dialyser," terms still in use.

Graham studied by the same method a number of similar preparations, one of which only need be mentioned. If a dilute solution of sodium silicate (the "waterglass" of commerce) is poured into dilute hydrochloric acid, silicic acid and sodium chloride are formed. If this mixture is now dialysed, the sodium chloride passes out and a perfectly clear and colourless solution of silicic acid remains in the dialyser, although this substance, which occurs in great quantities in nature, is almost completely insoluble in water. Both this solution and that of prussian blue, however, exhibit very striking differences from ordinary solutions of crystalloids beyond the fundamental one of not passing through the dialysing membrane. On addition of a few drops of any acid or salt solution the prussian blue is immediately coagulated and in a short while settles out as a flocculent precipitate, leaving the liquid quite clear and colourless. The silicic acid solution even undergoeds ma osrpeonvtiascnoeuosusdcehvaenigoepsona kbeweipsihngo:paitiegsrcaednucaellayndbeficonmaielys more an sets to a jelly; the change can be enormously accelerated by the addition of a few drops of am monia or even by bubbling carbon dioxide gas through the solution. Both these transformations are irreversible: neither the precipi tate of prussian blue nor the jelly of silicic acid can be re-trans formed into the original solution by washing or the like.

Graham gave the convenient name of so/ to a solution which did not dialyse, and the name of gel to its product of transforma tion; both terms have come into general use and will be employed in the rest of this article.

Earlier Observations.—Gra ham's method of preparing sols or colloidal solutions of many substances known to be insoluble was new and fundamental, but numbers of such apparent solu tions had been observed long be fore him. Berzelius (q.v.) had already noticed that silicic acid, sulphur and several metallic sulphides formed such solutions in certain conditions; Francesco Selmi (1817-81) had investigated prussian blue and sulphur sols and expressed very modern views on the constitution of these "pseudo-solutions," as he called them, and many other isolated observations are on record.

Of particular interest is the first systematic investigation of what is now called colloidal gold or gold sol, a preparation which has been of immense importance in the study of colloids. It was known already to the alchemists of the i7th century that very dilute gold chloride solutions, when treated with reducing agents, turned red or purple. In a paper entitled "On the experi mental relations of gold (and other metals) to light" published in the Philosophical Transactions in 1857, Faraday described such ruby and purple fluids obtained with various reducing agents and gave an extremely complete account of their properties. They were at once turned blue and eventually precipitated by traces of electrolytes; this change, which was irreversible, was even produced after a time by the minute amount of matter dissolved out of the glass vessels. Faraday expressed the definite view that the gold in these liquids was present in the form of extremely minute particles, much too small to be visible in the microscope; their presence could, however, be made evident "by gathering the rays of the sun into a cone by a lens and sending the part of the cone near the focus into the fluid"; the cone becomes visible which it would not be in a liquid entirely free from suspended particles.

This method of illumination was later used extensively by Tyndall and is generally known as the Tyndall cone; it has become one of the most delicate means of making small particles collectively visible in liquids or gases.

The Invention of the Ultra-Microscope—Faraday's paper was almost completely overlooked for about fifty years. Towards the end of the last century R. Zsigmondy (now professor at GOttingen) prepared "ruby liquids" similar to those of Faraday by a new method of reduction, which he at first described as "aqueous solutions of metallic gold." The question of their constitution—and that of most other sols—was however eventu ally solved by means of the "Ultra-microscope" (see MICRO scoPE), designed by Zsigmondy and H. Siedentopff (the scien tific adviser of the firm of Carl Zeiss) in 1903. In this instrument a small, but extremely intense, Tyndall cone is projected into the liquid and is viewed at a right angle to its axis with a micro scope. Particles which, for rea sons inherent in the formation of microscopic images, cannot be seen in the ordinary microscope on account of their small size, become visible in the ultra-micro scope as bright discs on a dark ground. The apparent size of the discs is no measure of the actual size of the particles which can, h owe v e r, be calculated from the number counted in a known volume of illuminated liquid and from the known con centration.

A very large number of sols have been examined with the ultra microscope since its invention and have been found to contain particles of very various sizes, the upper limit of which is rough ly Io0-1 Soµµ (Au= one-millionth of a millimetre ; this is the usual unit of ultra-microscopic measurements). The lower limit of visibility depends, apart from the intensity of the illumination, on the size of the particle and on the optical difference between its substance and that of the liquid; the difference is greatest with metallic particles, and, with sunlight as the source of illumi nation, gold particles of about 5 j.u can just be made visible.

The presence of particles within the range described and thus very much larger than even complicated molecules is the char acteristic of all colloidal solutions. Some substances, like albumin, gum arabic in cold and gelatin in warm water, are spontaneously dispersed, as the usual term is, into particles of such size ; inorganic compounds such as have been mentioned, and very many others, must be produced by reactions which, by suitable choice of concentration, temperature and other factors, are so controlled that the particles formed cannot grow beyond the limit of colloidal sizes. This result has now been achieved in many hundreds of cases, and it is clear that Graham's distinc tion between colloids and crystalloids as two different kinds of matter is no longer tenable. Sulphur crystallizes from solution in carbon disulphide, while common salt does so from aqueous solu tion; sols of sulphur in water and of salt in several organic liquids can, however, be prepared by a variety of methods. Although the term "colloid" is used for convenience, it now means, not a peculiar type of matter, but merely matter which is, or can be made to appear in, a particular state of subdivision. Some substances, which were among those investigated by Gra ham, invariably and spontaneously assume this state when brought into contact with a suitable liquid, while others have to be produced in conditions so controlled that the required subdi vision is brought about.

Brownian Movement and Stability.

When particles can be observed at all they are always seen to be in constant motion of a very peculiar kind ; they quiver and describe irregular paths, the distances traversed by small particles sometimes amounting to several times their diameter. The motion is not confined to ultra-microscopic particles, but was first observed in 1827 by Robert Brown, the botanist, with microscopic particles (pollen grains) . The motion, which is called the Brownian movement (q.v.) is now known to be caused by the impact of the molecules of the surrounding liquid on the particle, and its amplitude increases as the size of the particle decreases. The impacts take place in all directions and the fraction of component which acts vertically upwards is sufficient to counteract gravity and to keep the particles from settling out in the course of time ; in the absence of the Brownian movement even ultra-microscopic particles would shew appreciable sedimentation within a few hours or days.Although the particles move in all directions they never, in a stable sol, are observed to collide with one another. Since there is nothing in the nature of the movement itself to render such collisions impossible, there must be something in the particles themselves which prevents collision. What this factor is will become clear when we have considered the classification of sols.

Classification of Sols.

In spite of the great diversity of behaviour exhibited by individual sols two main types can be clearly distinguished, one resembling the Prussian Blue or the gold sol, the other the gum arabic or albumin sol. The first type is generally very dilute and strikingly sensitive to small concen trations of electrolytes, which produce immediate coagulation followed by settling out of the dispersed substance. The coagulum in the great majority of cases cannot be made to pass into col loidal solution again. On the other hand sols of the second type, e.g. of albumin, are not perceptibly affected by small electrolyte concentrations ; very high concentrations, such as saturation with ammonium sulphate, cause coagulation, but with this and some other salts the coagulation is reversible and the albumin disperses again when the salt is removed by dialysis. A somewhat similar effect is produced by alcohol or acetone, organic liquids which strongly attract water.Colloids of the first class are called lyophobic and those of the second lyophilic, i.e., translated literally, such as hate and such as like the state of solution, a classification adopted by Prof. Freundlich of Berlin and many authors. Prof. Wolfgang Ostwald of Leipzig distinguishes suspensoids and emulsoids; these classes coincide roughly, though not quite exactly, with the lyophobic and lyophilic respectively. These terms imply that the one class resembles suspensions, the usual description of a liquid in which solid particles are distributed, while the other resembles emul sions, which contain globules of one liquid distributed in another. The assumption that the particles in this class are liquid rests on inferences which are not generally accepted.

The Lyophobic or suspensoid sols shew a much more uniform behaviour than the lyophilic ones and may therefore be described first. They are all fairly dilute, concentrations of a few per cent being rarely exceeded, clear or slightly opalescent ; their colour may vary widely for a given substance: thus gold sols may be red, purple or blue, and silver sols any colour from blue through purple and red to yellow. Their common and most striking characteristic, the sensitiveness to electrolytes, has already been mentioned repeatedly. A further property common to all of them, whatever the chemical nature of the dispersed substance, is the existence of a difference of electric potential between the surface of the particles and the surrounding liquid. The conse quence is that in an electric field they move towards one pole, as was first shewn (for arsenic trisulphide sol) by S. Linder and H. Picton, working in Ramsay's laboratory in 1892. This phe nomenon, known as cataphoresis, is demonstrated in the simple apparatus illustrated in Fig. 1. The lower portion of the U-tube is filled with the sol to be investigated, while the limbs contain distilled water, into which dip two electrodes. When these are connected to an electric supply, the particles move towards the electrode of the sign opposite to that on their surface, and, if the sol is coloured, the boundary between it and the water above can be seen to move accordingly. It can now be shewn that the existence of the charge at the surface of the particles is necessary for the stability of the sol. By careful addition of electrolyte in small amounts the charge on the particles can be neutralized, which shews itself by their no longer travelling in the electric field; when this point is reached, or even before the potential difference is quite reduced to zero, the sol becomes unstable and eventually precipitates. The particles which, not withstanding the Brownian movement, did not collide while charged, now come into collision, adhere to one another and finally form aggregates sufficiently large to settle out.

Many theories, which cannot be discussed here, have been advanced to explain the origin of the potential difference, why it prevents collision is still obscure, although the facts are clearly established.

The great majority of lyophobic sols, like those of sulphur, the sulphides, ferrocyanides, gold, silver, platinum, etc. contain particles which are negatively charged towards the liquid and travel to the anode; the particles of a number of oxide sols, like those of iron, chromium, aluminium and cerium, are positive and travel to the cathode.

Electrolyte Coagulation.

The concentration of electrolytes required to bring about coagulation of a lyophobic sol (arsenic trisulphide) was investigated for the first time by Hans Schulze in 1882. He found that the concentration of salt depended on the nature of its metal or, as we now say, its cation and to a very marked degree on its valency. Potassium salts, with a univalent cation, had to be used in concentrations 4o-5o times as great as the corresponding salts of bivalent cations like magnesium or barium, and in concentrations about 50o times as great as the corresponding salts of a tervalent cation like al uminium. The coagulation of the arsenic trisulphide sol, with negative particles, was again studied with great thoroughness by Linder and Picton, who confirmed Schulze's results and ex tended his rule by examining the ferric oxide sol, the particles of which are positive. They found that in this case the valency of the acid or anion was the determining factor. A very consider able amount of study has since been devoted to the phenomenon, which substantially confirms the findings of the pioneer workers; the valency of the ion of the sign opposite to that of the sol particles determines the concentration required to produce coag ulation, but the ion which has the same sign makes itself felt by a slight antagonistic effect : thus potassium chloride or nitrate will coagulate a negative sol in somewhat lower concentration than potassium sulphate or citrate.

It has been mentioned as one of the chief characteristics of the second or lyophilic class of colloids that they are little affected by low electrolyte concentrations. If a lyophilic colloid in small amount is added to a lyophobic sol it imparts to it this enhanced resistance to electrolytes or, as it is usually called, "protects" it. This protective action had been observed already by Faraday, who noticed that the addition of "a little jelly" made his ruby fluids much more stable. Gelatin is, indeed, one of the most effective protective agents for gold sols; a few milli grammes per litre prevent coagulation by salt concentrations many times higher than those which precipitate the unprotected sol. Gum arabic, albumin and its products of decomposition as well as tannin act in the same way. Various body fluids contain mixtures of proteins which act as protective colloids; in the cerebrospinal fluid the protective effect is altered by various diseases and a diagnosis can be made by coagulating, by a stand ard sodium chloride solution, mixtures of the fluid with standard gold sol and noting the colour change produced (Lange's test, 1912).

The suspensoid of lyophobic sols are all laboratory products and, while of the greatest theoretical interest, do not play as important a part in nature or in the arts as do the lyophilic colloids. A number of sols, e.g. of ferric oxide, manganese dioxide, silver, selenium, sulphur, etc., are used in medicine; all sols made for this purpose are protected. Sols of graphite in water or oil find extensive use as lubricants. Coagulation by electrolytes is used in a number of processes to precipitate finely divided matter suspended in liquids and, indeed, occurs on a huge scale in nature ; clay and other particles carried down by rivers are coagulated on contact with salt water and are deposited to form such deltas as are present at the mouths of the Nile and the Mississippi.

Lyophilic Colloids.

The lyophobic colloids, however differ ent their chemical constitution, skew on the whole a remarkable uniformity of behaviour. The lyophilic colloids, on the other hand, exhibit very considerable variety and have no such striking feature in common as the electrolyte coagulation characteristic of all lyophobic sols. Nevertheless a fundamental similarity can be perceived when the properties of a few representatives of the group are surveyed and compared.

Albumin.

White of egg is a mixture of several proteins (q.v.) the most important of which, albumin, can be isolated by a simple procedure. The white is beaten to a froth, the clear liquid which drains from it suitably diluted, and sufficient ammonium sulphate is added to form a half-saturated solution. A precipitate forms, consisting of globulin, another protein, while the liquid contains albumin and ammonium sulphate, which can be removed by dialysis. The remaining sol of natural albumin can be shewn to contain negatively charged particles ; on the gradual addition of acid it loses the charge and at a fairly con stant acid concentration becomes neutral or "iso-electric" (Hardy, 1 goo) .Addition of neutral salts produces coagulation, but the con centrations required are enormously greater than those required for the precipitation of lyophobic sols, and in many cases, e.g. ammonium sulphate, amount to saturation. Salts fall into three classes according to their cation : salts of the alkalis form reversible coagula, which on dilution or dialysing out the salt disperse again; salts of the alkaline earths in about the same concentrations produce precipitates which are at first reversible but soon become permanently insoluble, while, finally, salts of the heavy metals produce irreversible precipitates in much smaller concentrations.

If salts of the first class with the same cation, say potassium or ammonium, are compared, it is found that the concentration required to precipitate or, as it is often called, "salt out" natural albumin depends markedly on the anion or acid. If the salts are arranged in increasing order of the concentrations required to produce coagulation, i.e. in decreasing order of their efficacy, the following sequence of anions is found: Citrate—Tartrate—Sulphate—Acetate—Chloride- ) The salts of the two anions in parenthesis do not salt out even in saturated solutions. This sequence, which is of fundamental importance in the theory of lyophilic sols, was found by Hof meister (Professor at Strasbourg) in 1888 and is generally called after him.

Albumin, like the majority of aqueous lyophilic sols, is also precipitated by alcohol; the concentration required is smallest at the iso-electric point, a significant fact to which reference will be made again.

Albumin finally undergoes a specific change familiar to every one when heated for some time above 65° C: it coagulates irre versibly. When concentrated it forms a stiff white gel (boiled white of egg), when dilute an opalescent sol which has distinctly lyophobic character and is precipitated by low electrolyte concen trations.

Another protein, glutin, is the principal constituent of a lyophilic colloid well known to most people, gelatin. If the sheet or powder, as which it occurs in commerce, is placed in cold water, it swells until it has taken up six to ten times its weight of water. On warming to about 3o° the gel disperses to form a faintly turbid sol which remains liquid above about 25° and on cooling "sets" to a jelly, the change being completely reversible.

High salt concentrations produce a stringy coagulum from the sol, and alcohol also precipitates gelatin. The most striking effect of salts, however, is shown in the viscosity of the sol and in the sol-gel transformation or setting. Here the Hofmeister series of anions appears again quite unmistakably : the salts at the beginning of the series make the sol more viscous, favour setting so that it takes place at higher temperature, and produce a stiffer jelly; these effects decrease towards the end of the series and the last members, iodide and thiocyanate, lower the viscosity of the sol, retard setting and, in sufficient concentrations, even prevent it altogether.

A substance shewing a behaviour quite parallel to that of gelatin, though differing from it profoundly in chemical consti tution, is agar, much used as a culture medium in bacteriology. It is prepared from a number of Japanese seaweeds and occurs in commerce as shreds or powder, the principal constituent of which is a carbohydrate (q.v.). In cold water the substance swells and on heating to boiling point forms a sol, which on cooling to about 3o° sets to a jelly at concentrations as low as o.2%. The effect of the Hofmeister series is again exactly the same as on gelatin, which excludes the possibility of ascribing it to any sort of chemical action ; the anions at the beginning favour setting, while those at the end retard or prevent it.

At sufficiently low concentrations the agar sol does not set to a jelly, and such dilute sols have been the subject of theoretical investigations of much importance (by Prof. Kruyt of Utrecht and his pupils) which afford an insight into the character of lyophilic sols .in general.

Agar sol, like many others of this class, is an almost clear liquid and shews no particles in the ultra-microscope, but only a diffuse cone of light. It has already been emphasized that two factors determine the possibility of making ultra-microscopic particles visible, sufficient intensity of illumination being assumed : the size and the optical difference between particles and medium. It is the latter which is small in lyophilic sols, in which however the existence of particles falling within the colloidal range can be demonstrated, and their size estimated, by indirect methods which cannot be discussed here. A starch sol, e.g., which in many respects resembles the agar sol closely, contains particles of about 14/1,A diameter. From the number of particles and the known quantity of dry starch used in making the sol it can however be calculated that this would account for particles of about 6yEu diameter only, so that we must conclude the starch to be somehow associated with sufficient water to make up the larger volume, i.e. one part of starch with about eleven of water. Such hydrated—as the usual term is—particles are present in all lyophilic sols.

The particles of the agar sol are negatively charged, and the charge can be neutralized by small additions of electrolytes of the same order of concentration as are necessary for the coagulation of lyophobic sols. The agar sol however shews no perceptible change when this has been done, so that there must be some factor other than, or additional to, the electric charge which keeps it stable. This factor is the hydration or water associated with the particles, as can be shewn by adding some liquid which strongly attracts water, such as alcohol or acetone, to the sol which has been rendered electrically neutral by small electrolyte concentrations: coagulation takes place as soon as sufficient alcohol has been added to produce dehydration, i.e. withdrawal of water from the particles. The inverse order of procedure confirms the result just described; on addition of alcohol to agar sol without electrolyte the clear liquid becomes opalescent and shews copious particles in the ultra-microscope. The withdrawal of water from them increases the optical difference between them and the surrounding liquid, so that, al though smaller, they become visible. The sol has, in fact, been transformed into a lyophobic sol, but is still stable because it retains its electric charge ; this can be neutralized in the usual way by small additions of electrolytes, which again bring about coagulation.

There are thus two factors which main tain the stability of the lyophilic sols, elec tric charge and hydration, and both have to be removed to bring about precipitation. Removal of the charge alone or dehydra tion alone alters the character of the sol but leaves the altered sols stable.

These considerations also elucidate satisfactorily the meaning of the Hof meister series, which has been mentioned several times. The action of salts in e.g.

salting out albumin is twof old : the first small addition neutralizes the charge, while the further large amounts required for coagulation act, like alcohol, by reducing the hydration of the particles. It is well known that the ions, into which the salts dissociate, are themselves hydrated, i.e.

attach water molecules to themselves, to very different degrees and in proportion to this degree of hydration withdraw water from the colloid particles. The ions also have an effect on the water, to which brief reference only is possible: water at ordinary temperature is known to contain multiple or associated molecules, and its solvent properties are dependent on the proportion of those of the "degree of association." The degree of association itself is proved to be affected by the presence of the ions of the Hofmeister series.

We have so far spoken of lyophilic colloids in water only, and experimental investigation has, until recent times, been largely confined to them and more particularly to the proteins. The reason is the enormous importance of the proteins in living organisms; to take a single example, blood or, more exactly, the serum in which the red and white corpuscles are suspended, is a sol containing a mixture of several proteins with different properties which have been gradually elucidated by the methods of colloid chemistry. There are however many lyophilic sols of the greatest importance in the arts, in which the medium is not water but an organic liquid or a whole group of such. Thus india rubber forms sols in many hydrocarbons like petroleum ether, benzene or toluene, and also in substituted hydrocarbons like carbon tetrachloride or tetrachloro-ethane ; the rubber solu tion used for mending tyres is a familiar example. Cellulose nitrates (one of which is gun-cotton) form sols in many organic solvents, such as acetone, glacial acetic acid, amyl acetate and in a mixture of ether and alcohol, though not in either of them separately. Cellulose acetate likewise forms sols in organic sol vents and is now one of the materials for the manufacture of artificial silk, as is another derivative of cellulose, viscose or cellulose xanthate. It may be of interest to mention in this connection that cellulose itself, though not dispersed either by water alone or by any organic solvent, forms sols in various concentrated salt solutions when digested under pressure.

The most striking and obvious characteristic of the lyophilic sols in organic solvents is undoubtedly their very high viscosity at low concentrations. A sol containing gm. of rubber in oo cc. of benzene may have a viscosity 50-8o times as high as that of the solvent, while sols of certain brands of cellulose nitrate in acetone at the same concentration have viscosities many hundred times that of the solvent. For comparison it may be worth mentioning that a 40% sugar solution has a vis cosity only 7.47 times as high as that of water at 15°. As there is generally a whole series of organic solvents available for every colloid of this class, it is possible to compare the viscosities produced by equal concentrations in a number of them, when it is found that they vary considerably in different liquids, a fact the significance of which will be discussed below.

The conditions which determine the stability of sols in organic solvents have not been studied to the same extent as those in aqueous sols. It is however fairly certain that electric charges, if present at all, do not play any great part, and that the prin cipal or only factor is solvation, i.e. some sort of combination with the liquid, by which a great portion of it is held by the particles just as water is held by the agar or starch particles. No particles can be seen in benzene-rubber sol, but they become visible after the addition of alcohol, which withdraws benzene from them as it withdraws water from agar particles.

Gels.

Reference has already been made to the products of- reversible or irreversible—transformation of sols, to which Gra ham gave the name of gels. The gels of the lyophilic sols, to which the term has now become more or less confined, are of particular interest and importance; one of the typical forms is the gel of gelatin, familiar to everyone in the shape of table jellies. These contain 5-6% of the dry substance and thus exhibit at once the most striking characteristic of gels : that they retain their shape and behave up to a point like solids, although consisting very largely of liquid.Gelatin gel is reversible : on warming it "melts" to sol, which on cooling sets again to gel. If the temperature is not raised above the melting point it can be dried without passing through the sol state until it contains in ordinary atmospheric conditions about i 5% of water ; the sheets or powder of commerce are such dry gel. A piece of this dry gel, placed in cold water, takes it up and swells, until the quantity taken up reaches 8-10 times its own weight, when the process stops. In thus swelling, the gel exerts considerable force, which can be measured by placing it in an enclosure permeable to water, but impermeable to the gel. An apparatus of this description (Posnjak, 1912) is shewn in sectional elevation in fig. 2. A cylindrical glass tube is luted at the lower end into a porous clay pot, while the upper end is closed by a screw cap. Discs of the gel to be examined, of exactly the same diameter as the inside of the tube, are placed on the bottom of the porous pot, and the whole tube is then filled with mercury, which reaches into the calibrated capillary tube. This is connected to a pressure gauge and a steel bottle containing compressed gas, by means of which any desired pres sure up to about 6 atmospheres can be put on the mercury and through it on the gel. The lower end of the tube is placed in a vessel containing water, which passes through the porous clay cell to the gel, and the increase in volume of the latter can be calculated from the displacement of the mercury column in the capillary. In this way it has been found that gelatin, in taking up about half its weight of water, can overcome a pressure of about 5 atmospheres ; in other words, this pressure has to be exerted on it to prevent it from swelling further. The first portions of water have the greatest effect, but when the gel has taken up over twice its weight of water it still exerts a pres sure of about 0.5 atmospheres.

The swelling of gelatin is very greatly affected by electrolytes; all acids in low concentrations increase it markedly, but have the opposite effect when an optimum concentration has been exceeded. The effect of salts is still more complicated and cannot be briefly summarized here.

It may be mentioned here in parenthesis that a large number of organic tissues share with simple gels the property of swelling in water ; the swelling of wood even in moist air, that of dry peas in water, etc. and the great forces exerted in these processes are everyday examples. The proper water content (or degree of swelling) of such living tissues as consist of proteins depends, , like that of gelatin, on the electrolyte content and especially on the reaction, which healthy organisms regulate within very narrow limits.

As mentioned, gelatin gels containing as little as 5% of dry substance retain their shape, while those of 10-15% are suf ficiently strong to permit a study of their elastic properties. Their Young's modulus has been determined by several observers and has been found to be of the order of grammes per sq. cm. and roughly proportional to the square of the gelatin content. Further investigation shews that the gel combines in a curious way the properties of the solid and liquid state. The volume remains almost exactly constant during deformation, a behaviour caused by the low compressibility of the liquid portion ; if the deformation is maintained beyond a short time, the gel yields and the force required to maintain a given deformation, say a given elongation in a stretched rod, becomes less and less with time. Gels free from strain are, like liquids, optically isotropic, but when strained become double refracting (see LIGHT), as is revealed by examination in polarized light. When the stress is applied for a considerable time, and especially if the gel is dried while stressed, the double refraction remains permanent ; it is a curious and significant fact that many structural elements of organisms, which consist of gels or mixtures of such, always exhibit double refraction.

A gel very similar to gelatin gel is that of agar, which has received comparatively little study so far. The gelatinizing prop erties of agar are much more marked than those of gelatin : a concentration of I% is sufficient to form a fairly stiff gel. Owing to this property and to its being tasteless, as well as difficult to detect by chemical tests, agar has been much used for adulter ating jams and jellies.

Lyophilic gels in which the liquid constituent is an organic solvent are also numerous and interesting. Cellulose acetate and benzyl alcohol behave exactly like gelatin and water : the acetate swells in the cols solvent, disperses on warming to about 40° to form a sol, which on cooling sets to a jelly resembling gelatin gel in appearance and elastic properties. Both natural and vul canized rubber swell in hydrocarbons, although the latter does not form sols. The volumes of liquid taken up and the pressures generated are much greater than with gelatin : rubber, when it has taken up about 3.5 times its weight of benzene, still exerts a pressure of over 5 atmospheres. Rubber swells in a great number of organic liquids, but to very different degrees, which have been determined by several observers, who find that e.g. the quantity of carbon tetrachloride or of chloroform taken up is almost double that of benzene or toluene. Here a remarkable parallelism with the viscosity of sols shews itself : sols of equal concentration in carbon tetrachloride or chloroform are much more viscous than those in benzene. The inference is natural that the sol particles themselves are more "swollen" in the sol vents containing chlorin than in the simple hydrocarbons, which would explain the higher viscosity of the sols in the former.

The gels described so far dry without the formation of any pores or voids; at no stage will they imbibe liquids other than those which have the specific effect of causing swelling. No or ganic liquid will penetrate into dry gelatin, nor water or aqueous solutions into dry rubber. A different behaviour is shewn by a number of gels, the most important representative of which is that of silicic acid. It has already been mentioned that this gel forms, spontaneously or on addition of electrolytes, from the sol and that it is a transparent or translucent mass with bluish opalescence. Unlike gelatin gel it cannot be deformed, but is brittle. Gels containing about go% of water can be handled and keep their shape; on drying they shrink considerably and finally turn to a perfectly transparent mass resembling glass, but much lighter. If the gel is placed in water during any stage of the dry ing process it does not take up water and swell; it is therefore generally described as a rigid gel, in contradistinction to the type represented by gelatin and rubber, which are known as elastic gels.

When the gel has reached the glassy stage it still contains some water, which can be removed over concentrated sulphuric acid or at higher temperature ; in this final drying, however, the volume undergoes no further reduction. The gel has now become a porous mass and the last stage of drying merely removes water con tained in the pores. The existence of the pores can be easily demonstrated by immersing the gel in a liquid : air bubbles escape and the gel imbibes the liquid, of course without change of volume. The pores can be shewn by methods which cannot be described here to be of ultra-microscopic diameter. A gel resembling these artificially prepared ones is found in the internodial spaces of the bamboo; the optical properties of this substance, which is known as tabasheer and credited with curative properties, were investi gated by Sir David Brewster 0819). Various forms of silica found in nature, such as opal and agate, probably originated from gels dehydrated under considerable pressure. Moist silicic acid gel has been found in fissures during the construction of the Simp lon tunnel, and in mining operations in Australia.

Gelatin gel can be transformed into a rigid gel by the action of various agents, the most energetic of which is formaldehyde. The gel thus treated is quite brittle and no longer swells in water, nor disperses when the temperature is raised.

Diffusion and Reactions in Gels.—A further property of gels traceable to their high content of liquid is the small resistance which they offer to the diffusion of dissolved substances. This can be shewn by half filling test tubes with say 5% gelatin, allowing it to set and then pouring on the gel solutions of coloured salts or some of the simpler dyes, like fuchsin or fluorescein ; the colour will be seen to penetrate fairly rapidly into the jelly. Graham, who carried out the first quantitative investigations on the rate of diffusion of a number of substances, found that it was not much lower in dilute gels than in the pure solvent and many measure ments have been carried out in such, as the difficulties arising from vibration and convection are eliminated. In more concentrated gels, however, the rate of diffusion is markedly reduced. Colloidal solutions, which do not pass through,membranes, do not diffuse into gels either, and the simple test described above can there fore be used—instead of dialysis—for deciding whether a given solution is colloidal. If a gold or other coloured sol is placed on the gelatin gel, no trace of colour shews in the latter even after days.

Since dissolved substances diffuse readily into gels, it is possible to allow reactions between two of them to proceed in such media either by letting the two solutions diffuse into a cylinder of the gel from opposite directions, or else by dissolving one of the sub stances in the gel itself and placing an aqueous solution of the other on it. The results are of considerable interest when one of the products of the reaction is an insoluble precipitate : as the solutions mix very gradually and as the first particles of precipi tate are held fixed by the gel, thus acting as nuclei for further material, the conditions are favourable for the formation of large crystals. Many substances which are precipitated from aqueous solutions as microscopic particles only, can be obtained as large crystals when the reaction is produced in a gel, especially that of silicic acid ; even metals can be obtained in well developed crys tals of several mm. e.g. as glistening tetrahedra and gold as bril liant hexagonal plates.

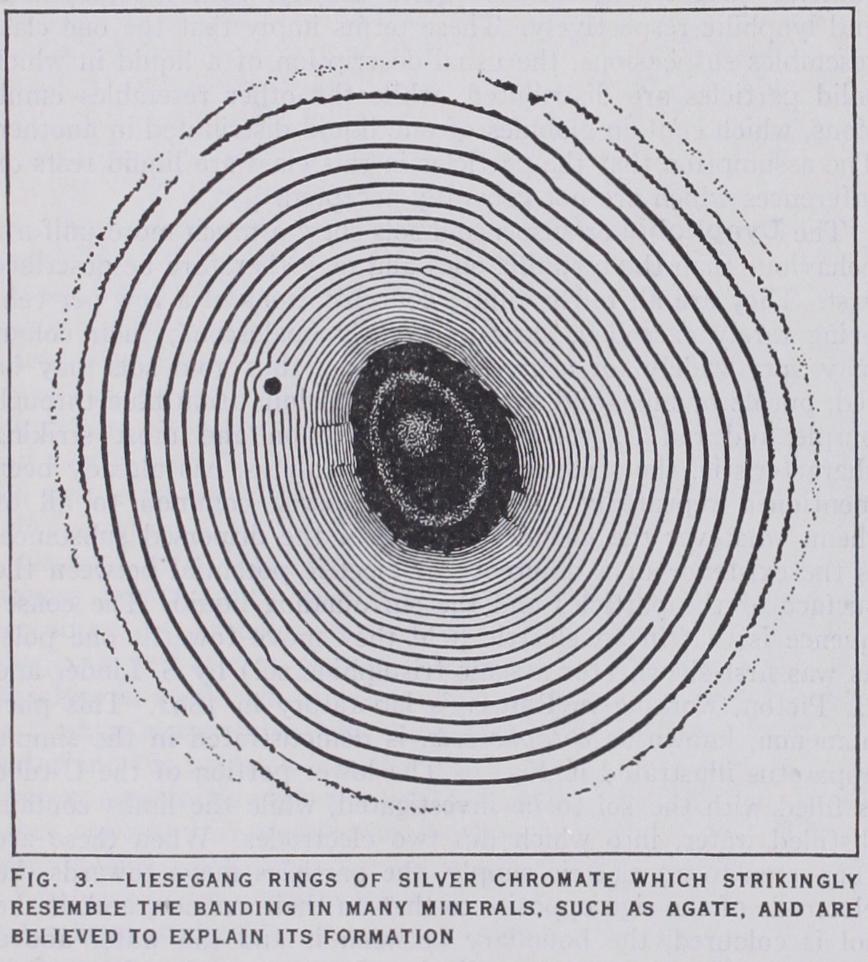

The Liesegang Phenomenon.—An extremely curious phe nomenon, generally called after its discoverer, R. E. Liesegang (Frankfurt), is observed with certain reactions. The original ex periment is as follows : a thin layer of gelatin gel containing a little potassium dichromate is prepared on a glass plate, and a drop of strong silver nitrate solution placed in the centre. The silver nitrate at once diffuses into the gel and reacts with the dichromate, forming dark red, insoluble silver chromate and potas sium nitrate. Diffusion proceeds continuously and it would seem that the precipitation of silver chromate should likewise be con tinuous and should lead to the formation of a gradually widening band of precipitate round the original drop. What actually hap pens, however, is that the chromate appears in a number of con centric rings separated by clear intervals, which become wider as the distance from the centre increases. (Fig. 3.) Similar results can be obtained by placing gel containing one substance in the lower half of test tubes and pouring the solution of the other sub stance on it, in which case parallel strata of precipitate are formed at increasing distances from each other. Fig. 4 shews diagram matically the position of strata of magnesium hydroxide produced by letting a solution of ammonia diffuse into a gelatin gel contain ing magnesium chloride; the spaces between the strata are per fectly clear.

Many other reactions have been found, in carefully adjusted concentrations, to give similar stratifications, and investigation has also shewn that the gel does not take a passive part only, by securing quiet diffusion and fixing the precipitate where it is formed, but has a specific effect. Thus lead iodide and lead chro mate form beautiful stratifications in agar, but not in gelatin, while on the other hand silver chromate forms them in gelatin, but not in agar.

Various interesting theories have been propounded to explain the phenomenon, none of which has found general acceptance or covers all the facts; in particular, most of them fail to explain the very marked specific effect of the gel.

Syneresis.—All gels at certain concentrations, specific for each substance, shew a characteristic phenomenon : they spontaneously contract with exudation of liquid. Graham, who first described this behaviour, called it syneresis (from the same Greek root as heresy, a separation or splitting off). Silicic acid shows it at high concentrations; sols can be prepared which set within a minute to gels apparently dry on the surface and adhering to the vessel. After about ten minutes the surface is covered with minute drops of liquid and in an hour so much liquid has exuded between the walls of the vessel and the gel that the latter can be tipped out. Gelatin and agar, on the other hand, exhibit syneresis at low con centrations only ; so do some gels with organic solvents, like that of vulcanized india rubber, which contracts to Rio of its volume in a few days. The syneretic liquid is not pure solvent but always contains some colloid.

The Sol-Gel Transformation.—The formation of a gel, with some of the properties of a solid, from a sol which may contain as little as o•5% of dry matter (agar) is an extremely striking change, which has very naturally been the subject of much specu lation. Most gels are not differentiated in the ultra-microscope, so that theory has to rely on inferences from their known proper ties. The most generally received opinion is that the particles somehow join up to form chains and a network, or "ramifying aggregates," which some investigators (McBain) assume to be, to some extent, present already in the sol and to account for its viscosity. It is also probable that such a linking-up is accom panied by some change in the hydration of the particles. In any case, there must almost certainly be continuous liquid paths through a gel, to account for the ease with which diffusion pro ceeds through it.

Colloids in Nature and the Arts.—This necessarily brief account of the chief properties of a few typical colloids would be incomplete without a few words on the part played by colloids in nature and in the arts. Their importance in nature it is impossible to exaggerate : all organisms consist very largely of colloidal ma terial, or more precisely of complicated mixtures and intricate structures composed of such. While the simple sols and gels of the laboratory are but the crudest models of even the simplest organic structures, the knowledge gained from their study is providing, if not a solution, new and promising methods of attack on problems which have proved intractable by the methods of physical chemistry. The selective permeability of cell membranes, e.g. to different ions is one of these problems, which any theory of solutions fails to explain, but for which known properties of colloidal systems provide at least a parallel.

As regards the arts, many of the oldest, like bread making, tanning, ceramics or dyeing, employ typically colloidal material and have empirically attained a high degree of perfection. In these the part of science is to find rational explanations of meth ods discovered by accident and improved by trial and error, and colloid science is playing this part successfully. The study of gelatin has thrown a great deal of light on obscure features of the tanning process; a study of the electric charges on dye parti cles and fibres has elucidated methods of dyeing, and so on. The industries just mentioned are of prehistoric origin, but even the processes which go on in so modern and astonishingly perfect a product as the photographic dry plate remained very obscure until the behaviour of colloidal silver and silver compounds embedded in a gel received systematic investigation.

More recent industries, the rise of which has coincided with the modern development of colloid chemistry, like the artificial silk and the rubber industry, have benefited much more directly. Some of the most important new developments, especially in the manufacture of rubber goods, are direct applications of theoretical knowledge. It may be mentioned that a recently published work dealing with colloids in the arts runs to over a thousand pages.