Compton Effect

COMPTON EFFECT. The Compton Effect is the change in quality of a beam of X-rays when it is scattered. Imagine that a piece of paper when held between the eyes and a green light appears green, but that when the paper is moved to a position at right angles with the light its colour changes to yellow, and when turned to the opposite side from the light its colour becomes red. Such a change in colour would correspond to the increase in wave-length which X-rays undergo when they are scattered, a small change when scattered at a small angle, but a larger differ ence for the rays scattered at a large angle. This phenomenon owes its chief interest to the fact that it indicates a corpuscular structure for X-rays.

History.—The earliest experiments on secondary X-rays showed a difference in the penetrating power of the primary and the secondary rays. Barkla and his collaborators found (1908 ) that the secondary X-rays from heavy elements consist mostly of fluorescent radiations characteristic of the radiating element, and that it is the presence of these fluorescent rays which is chiefly responsible for the greater absorbability of the secondary rays. Later experiments, showed, however, a measurable difference in penetration even for the rays coming from light elements, such as carbon, from which no such fluorescent rays are emitted. It was established by J. A. Gray (192o) that in such cases the change in quality was an accompaniment of the process of scattering or diffuse reflection of the primary X-rays. A spectroscopic study of the scattered X-rays by A. H. Compton (1923) revealed the fact that different primary wave-lengths are increased in wave-length by the same amount when the rays are scattered, and he showed at the same time that this change could be explained if the X-rays are corpuscular in nature.

The Experiment and Its Explanation.

According to the theory that X-rays consist of electromagnetic waves, scattered X-rays are similar to an echo. When an X-ray wave passes through a piece of paper composed of electrons, each electron is set in vibration by the wave and, because of its forced vibrations, emits a new wave which goes in all directions as a scattered X-ray. The number of vibrations of these new waves per second is the same as the number of vibrations of the electron, which is in turn the same as the frequency of the original X-rays. Experiment, however, shows that the frequency of the scattered rays is less than that of the primary rays. This prediction of the wave theory of X-rays is thus incorrect.The corpuscular theory of the scattering process supposes that each X-ray particle, or "photon" may collide with an electron of the scattering material and bounce off. In fig. 1 is shown a dia gram of such a collision. The photon strikes the electron at 0, and bounces off toward P, while the electron recoils from the im pact in the direction OQ. The collision is supposed to be elastic; but a part of the energy of the photon is spent on the recoiling electron. It follows that the de flected or scattered photon must have less energy than it had be fore the collision. Such a decrease in the energy of the photon would be described in the language of the wave theory as a decrease in frequency or an increase in wave-length of the scattered X ray. (See QUANTUM THEORY.) As we shall show later, the photon theory can be put in a quantitative form, in which it pre dicts an increase in wave-length of the X-rays due to the scatter ing process of 2.42X (I cos 4) centimetre, where (kis the angle between the primary and the scattered rays.

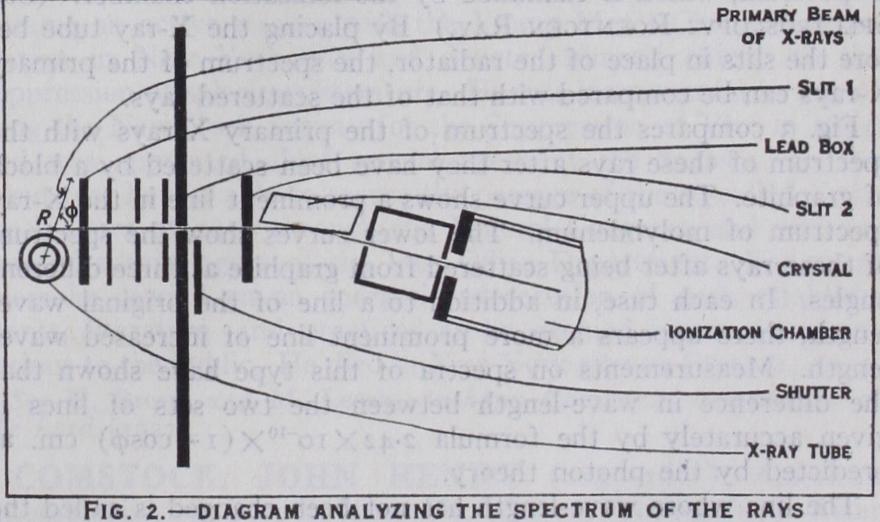

A diagram of the apparatus used for testing this prediction is shown in fig. 2. X-rays pass through a radiator R, which may be for example a block of carbon or paraffin. Some of the rays are scattered through slits 1 and 2 into the X-ray spectrometer. In this instrument a crystal of cal cite takes the place of the prism or the grating of an optical spec trometer and spreads the rays into a spectrum, which is examined by the ionization chamber. (See