Fugues

Fugues. In the polyphonic i6th century motets the essentials of canonic effect are embodied in the entry of one voice after another with a definite theme stated by each voice, often at its own convenient pitch, thus producing a free canon for as many parts as there are voices, in alternate intervals of the 4th, 5th and octave, and at artistically proportionate distances of times. It is not necessary for the later voices to imitate more than the opening phrase of the earlier, or, if they do imitate its continuation, to keep to the same interval.

Such a texture differs in no way from that of the fugue of more modern times. But the form is not what is now understood as fugue, inasmuch as i6th century composers did not normally think of writing long movements on one theme or of making a point of the return of a theme after episodes. With the appear ance of new words in the text, the i6th century composer naturally took up a new theme without troubling to design it for con trapuntal combination with the opening; and the form resulting from this treatment of words was faithfully reproduced in the instrumental ricercari of the time. Occasionally, however, breadth of treatment and terseness of design combined to produce a short movement on one idea indistinguishable in form from a fughetta of Bach; as in the Kyrie of Palestrina's Missa Salve Regina. But in Bach's art the preservation of a main theme is more necessary the longer the composition; and Bach has an incalcu lable number of methods of giving his fugues a symmetry of form and balance of climax so subtle and perfect that we are apt to forget that the only technical rules of a fugue are those which refer to its texture.

In Die Kunst der Fuge Bach has shown with the utmost clear ness how in his opinion the various types of fugue may be clas sified. That extraordinary work is a series of fugues, all on the same subject. The earlier fugues show how an artistic design may be made by simply passing the subject from one voice to another in orderly succession (in the first example without any change of key except from tonic to dominant). The next stage of organiza tion is that in which the subject is combined with inversions, augmentations and diminutions of itself. Fugues of this kind can be conveniently called stretto-fugues.' The third and highest stage is that in which the fugue combines its subject with con trasted counter-subjects, and thus depends upon the resources of double, triple and quadruple counterpoint. But of the art by which the episodes are contrasted, connected climaxes attained, and keys and subtle rhythmic proportions so balanced as to give the true fugue-forms a beauty and stability second only to those of the true sonata forms, Bach's classification gives us no direct hint.

A comparison of the fugues in

Die Kunst der Fuge with those elsewhere in his works reveals a necessary relation between the nature of the fugue-subject and the type of fugue. In Die Kunst der Fuge Bach has obvious didactic reasons for taking the same subject throughout; and, as he wishes to show the extremes of technical possibility, that subject must necessarily be plastic rather than characteristic. Elsewhere Bach prefers very lively or highly characteristic themes as subjects for the simplest kind of instrumental fugue. On the other hand, there comes a point when the mechanical strictness of treatment crowds out the rhetorical development of musical ideas ; and the 7th fugue (which is one solid mass of stretto in augmentation, diminution and inversion) and the i ath and i3th (which are inverted bodily) are academic exercises outside the range of free artistic work. On the other hand, the fugues with well-developed episodes and the fugues in double and triple counterpoint are perfect works of art and as beautiful as any that Bach wrote without didactic purpose. The last fugue Bach worked out up to the point where three subjects, including the notes B, A, C, H, were combined. It has been found that the theme of the rest of Die Kunst der Fuge makes a fourth member of the combination and that the combination inverts. This accounts for the laborious exercises shown in the i ath and i 3th fugues. It is high time that teachers of counterpoint took Die Kunst der Fuge seriously.Fugue is still, as in the i6th century, a texture rather than a form; and the formal rules given in most technical treatises are based, not on the practice of the world's great composers, but on the necessities of beginners, whom it would be as absurd to ask to write a fugue without giving them a form as to ask a schoolboy to write so many pages of Latin verses without a sub ject. But this standard form, whatever its merits may be in com bining progressive technique with musical sense, has no connection with the true classical types of fugue, though it played an interest ing part in the renascence of polyphony during the growth of the sonata style, and even gave rise to valuable works of art (e.g. the fugues in Haydn's quartets, op. 2o).

One of its rules was that every fugue should have a stretto. This rule, like most of the others, is absolutely without classical warrant ; for in Bach the ideas of stretto and of counter-subject almost exclude one another except in the very largest fugues, such as the nand in the second book of the Forty-eight; while Handel's fugue-writing is a masterly method, adopted as occasion requires, and with a lordly disdain for recognized devices. But the pedagogic rule proved to be not without artistic point in later music ; for fugue became, since the rise of the sonata-styles a contrast with the normal means of expression instead of being itself normal. And while this was so, there was considerable point in using every possible means to enhance the rhetorical force of its peculiar devices, as is shown by the astonishing dramatic fugues in Beethoven's last works. Nowadays, however, polyphony is universally recognized as a permanent type of musical texture, and there is no longer any reason why if it crystallizes into the 'For technical terms see articles COUNTERPOINT and FUGUE.

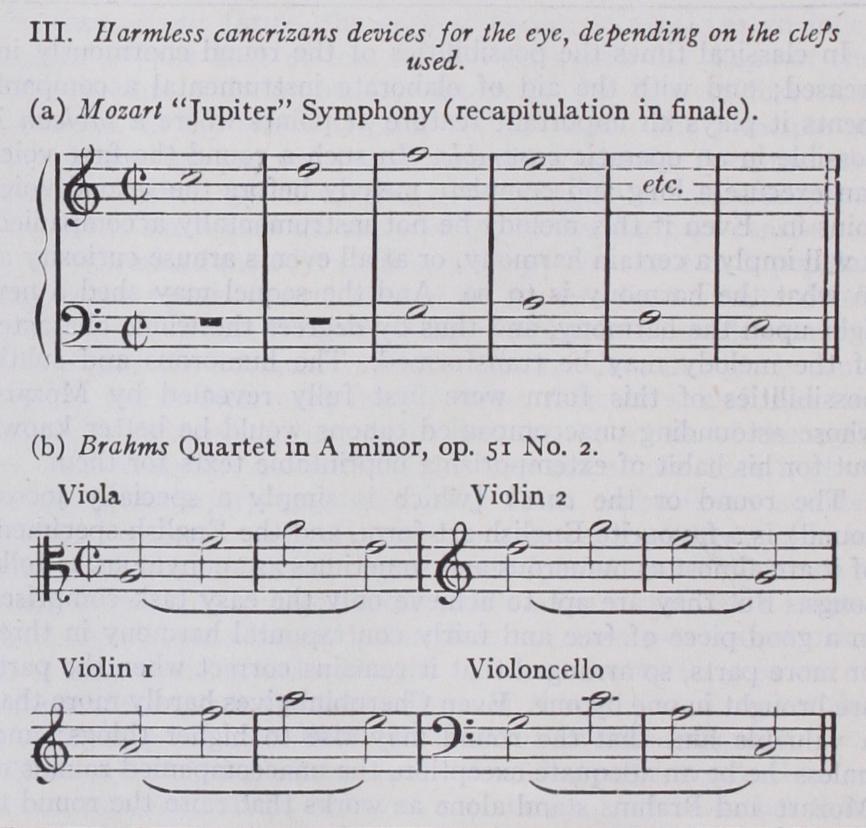

fugue-form at all it should not adopt the classical rather than the pedagogic type. It is still an unsatisfied wish of accurate musicians that the term fugue should be used to imply rather a certain type of polyphonic texture than the whole form of a com position. We ought to describe as "written in fugue" such passages as the first subjects in Mozart's Zauberflote overture, the andantes of Beethoven's first symphony and C minor quartet, the first and second subjects of the finale of Mozart's G major quartet, the second subject of the finale of his D major quintet, and the expo sition of quintuple counterpoint in the coda of the finale of the Jupiter Symphony, and countless other passages in the develop ments and main subjects of classical and modern works in sonata form.