Influence of Chemical Constitution

INFLUENCE OF CHEMICAL CONSTITUTION The sensation of white light is caused by electromagnetic vibra tions of a certain wave length impinging on the retina of the eye. The sensation of colour is produced by the absorption of one or other of the coloured components of white light when the light strikes some suitable surface or passes through a suitable medium —the light reflected from the surface or transmitted through the medium consequently conveying to the retina a sensation of colour complementary to that absorbed. There is an analogy be tween variations of colour in light and pitch in sound.

Many substances do not absorb any definite portion of the visible spectrum—the name applied to the range of colours into which white light can be resolved—but give general absorption throughout the range.

Such substances appear, therefore, colourless both by trans mitted and reflected light and it is only those materials which cause selective absorption, that is which absorb some definite portion of the visible spectrum, that appear coloured. It follows, therefore, that there must be some special property possessed by substances which produce the sensation of colour which distin guishes them from other substances that appear colourless.

As a matter of fact it is quite easy to detect the causes leading to the main underlying difference between the two types, for they may be divided into two classes which, for the sake of conven ience, may be named the physical cause and the chemical cause; and, in the first instance at any rate, the reason for production of colour is quite clear and it is a comparatively simple matter to reproduce the effect mechanically. For example, white light is resolved into its component colours when it is allowed to impinge on a glass surface which has been ruled with a number of fine lines, and there are a number of other ways by which the sensa tion of colour can be imparted by purely mechanical means.

As a matter of fact many natural objects, especially in the animal kingdom, owe their colour to the physical cause. The vivid green of certain beetles, the colours of the peacock's feathers, the colours of butterflies' wings and the colour of blue eyes are all produced in this way, the colour effect being caused by the interference of white light through the agency of minute excrescences or fine filaments on the surface of the objects that appear coloured. The colour effects in such cases are, therefore, subjective and it would be just as reasonable to attempt to ex tract a coloured substance from the peacock's feather as it would be to do so from the rainbow.

On the other hand there are a great number of substances the colours of which must be ascribed to the second or chemical cause. These occur both naturally and artificially and are dis tinguished from those of the first or physical section by reason of the fact that the coloured substances in them can be extracted from the coloured materials and, when extracted, are found to be definite chemical compounds which owe their colour to their chemical constitution. In nature such coloured substances are to be found mainly in the vegetable kingdom, in the colouring mat ters, for example, of the flowers and of green grass or leaves. Moreover, it is easy to distinguish by a practical test between the two types because if a peacock's feather is viewed by transmitted light the brilliant colours will disappear, whereas, if a red rose leaf is treated in the same manner no change in colour will be noticed.

Nevertheless, it is only reasonable to suppose that the two types of phenomena are of the same order and that whilst the physical or subjective colour is due to the intermolecular inter ference of white light, the chemical colour is due to intramolecular interference, or, in other words, white light is "filtered" through the molecular structure of the chemical substance, leaving a "por tion" behind in its passage. The colour is therefore dependent on the chemical composition of the particular compound. It remains then to compare those chemical compounds which produce colour with those that are colourless so as to reach some conclusion as to the influence of molecular structure on colour production. In the first place, however, it is necessary to attempt to arrive at some definition of what is meant by colour in a strictly scientific sense.

The Spectrum.

The range of the visible spectrum which is produced, for example, when a beam of white light passes through a quartz prism, represents a range of electromagnetic vibrations of wave lengths between 4,00o and 8,000 Angstrom units. This is, however, only one octave in the range of 62 octaves of wave lengths from o•oi to 3.5X Angstrom units which has been investigated. It is clearly, therefore, scientifically illogical to re strict the term "coloured" to those substances which cause ab sorption only in the short region capable of detection by the eye, because a substance which produces selective absorption in any other region of the electromagnetic range is also "coloured" al though such colour requires the aid of some external influence in order that it may be detected.It is necessary, therefore, to distinguish between visible colour and invisible colour and to describe those substances which give selective absorption in the visible region as visibly coloured and those which give selective absorption in other regions as invisibly coloured.

Infra-red and Ultra-violet Regions.—It is fortunate that the photographic plate is more sensitive to waves immediately out side the visible region of the spectrum than is the eye, for by its aid it is possible to detect selective absorption in those regions immediately outside the visible spectrum, which are known as the infra-red and the ultraviolet, and thus to show that many substances which appear colourless to the eye possess neverthe less intense invisible colour. Moreover, it is possible by simple chemical reactions to transform compounds having this invisible colour into those having visible colour or, in other words, by a change of structure, to throw the absorption from the invisible region into the visible region. In this way it is possible to corre late structure with visible colour.

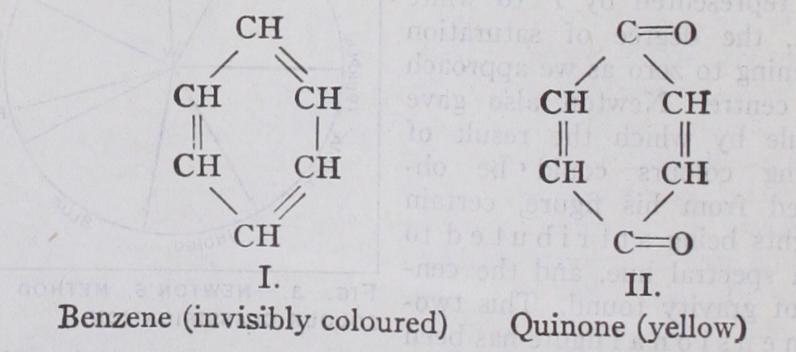

For example, the hydrocarbon benzene (CEO appears colour less to the eye both by reflected and transmitted light, neverthe less when its spectrum is photographed marked selective absorp tion in the ultra-violet region is manifested. Benzene is, there fore, a substance having a strong invisible colour. By a simple series of reactions it is possible to transform benzene (I.) into quinone (II.) and by so doing to shift the absorption from the invisible to the visible region of the spectrum, thus obtaining visible colour (yellow).

Absorption.—This change, in the case of many derivatives of benzene, takes place with remarkable ease and with astonishing rapidity, thus the change from phenol-phthalein (III.), the ben zenoid or invisibly coloured form, to the sodium salt (IV.), the quinonoid or visibly coloured form, by the action of alkali, and the reverse change which is effected by the action of acid, is so rapid and sensitive that the substance is used as an effective indicator in alkalimetry.

The hydrocarbons naphthalene (Cio1-18) and anthracene provide further examples of the same kind and, in fact, the occurrence of colour among organic compounds which has led to the foundation of the coal-tar colour industry is based mainly on this change.

It is also possible to start with a benzenoid derivative which by reason of its structure is visibly coloured and by a simple chemical change, such as that illustrated above, to throw ab sorption from one end of the visible spectrum to the other and thus to transform a red substance into a blue one.

As a matter of fact Nature has utilized this method to produce her red and blue flowers. The red flowers are those in which the cell sap is acid, the blue those in which it is alkaline. If the cell sap is neutral the flowers are purple. (See also ANTHOCYANINS.) It would appear, therefore, that the occurrence of visible colour is mainly adventitious end depends on molecular conditions which are subject to control. It happens to be a property of the quinone ring because the parent substance benzene possesses the power of causing absorption just outside the visible region. Even so, the formation of the quinone ring may not shift the absorption of benzene far enough to bring it within the visible region, and there are thus derivatives of quinone which have no visible colour. On the other hand the shift of the bands may be caused by other structures and there are, in consequence, derivatives of benzene such as azobenzene, C61-1,—N=N—C6115, to which no quinone structure can be assigned, yet which possess strong visible colour.

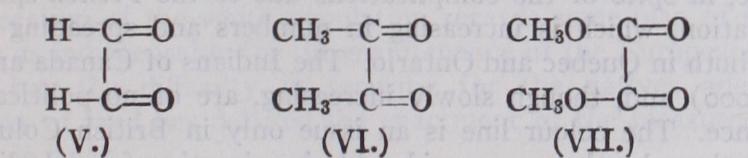

If the wider definition of colour be accepted it is probable that there is no such thing as a colourless material, because it is likely that every substance gives selective absorption somewhere within the range of electromagnetic vibrations. It appears to be in the power of many substances belonging to the aliphatic series of organic chemistry to give selective absorption in the infra-red region of the spectrum. Visibly coloured substances in this por tion of organic chemistry are not of frequent occurrence, but when such colour occurs it is always associated with the presence of what is known as the conjugated system of double linkages; thus glyoxal (V.) and diacetyl (VI.) are yellow :— Methyl oxalate (VII . ) is, however, visibly colourless and it must be assumed that in this case the infra-red absorption has not been thrown into the visible region. It is of interest to note that the same system of conjugated linkages is present in the con ventional formula for benzene (I.).

Colour in Chemistry.

It is also significant that visible colour is shown only by unsaturated carbon compounds and that in no case has a visibly coloured saturated compound been pre pared. It follows therefore :—That both visible and invisible colour are associated with unsaturation. That they are associated with the occurrence of selective absorption either outside or within the visible region of the spectrum, the former causing in visible, and the latter visible colour. That occurrence of this ab sorption is bound up with the presence of a system of conjugated double linkages within the molecule. (See also DYES, SYNTHETIC.) The causes leading to the production of visible colour in in organic compounds will not be clearly understood until more is known about the molecular structures of such substances. It is obviously due, initially, to the presence of a colour-producing element such as copper, chromium, cobalt, etc. The cause of colour in these elements is probably molecular, as instance the change in colour iodine undergoes when heated. Nevertheless the structure of the salt must also play a part as is shown, f or ex ample, in the disappearance of the blue colour of hydrated copper sulphate when it loses part of its water of hydration. In any case the causes of visible colour in this section of chemistry are not so clearly defined as they are in the organic section, and no use ful purpose would be served by dealing with them in the present state of our knowledge.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-C.

Graebe and C. Liebermann, Berichte der Bibliography.-C. Graebe and C. Liebermann, Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft, vol. 1, p. Io4 (1868) ; Sir W. N. Hartley, Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc., vol. 17o (1899) ; W. Ostwald, "Ab sorption Spectra of Solutions," Zeits. f. Physikalische Chemie, vol. 9 (1892) ; Dr. H. Kauffmann, "Farbe und Konstitution," Ahrens' Vortrage, vol. 9 0904) ; Sir W. N. Hartley in H. Kayser's Handbuch der Spektroscopie, vol. 3 (1905) ; R. Willstatter, Ber. d. Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft, vol. 41 0908); H. Ley, Die Beziehungen zwischen Farbe und Konstitution bei Organischen Verbindungen (19ii) ; R. Willstatter, Ber. d. Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft, vol. 47 (1914) ; M. Wheldale, The Anthocyanin Pigments of Plants (1916) ; E. R. Watson, Colours in Relation to Chemical Constitution 0918) ; A. G. Perkin and A. E. Everest, The Natural Organic Colour ing Matters (1918) ,• G. C. T. von Georgievics, Die Beziehungen zwischen Farbe und Konstitution bei Farbstoffe (Zurich, 1921) ; Hon. V. A. H. Onslow, Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. B., vol. 211 (1923).(J. F. T.)