Dedifferentiation

DEDIFFERENTIATION, a biological term meaning the reverse of differentiation, i.e., for processes which lead to organ isms or their parts reverting to greater simplicity; the term reduction has also been employed, but is unsatisfactory as it is in demand for chromosome-reduction. (See CYTOLOGY.) Dedif ferentiation in its strict sense should not be applied to simple cases of degeneration, but in practice it is often impossible to draw the line.

Dedifferentiation in many Protozoa (q.v.) may be a regular and physiological phenomenon. When Protozoa with complicated structure, such as many Ciliates, reproduce by simple fission, many of the old structures dedifferen tiate, the daughter-cells acquiring new organs of the same kind by new differentiation. In Bursaria, Lund has shown that, in addition, damage or unfavourable con ditions will cause the whole ani mal to revert to a sphere without any trace of normal differentia tion. Redifferentiation to the normal form may occur from this state or from any stage in the process. Similar total dedifferen tiation occurs in the encystment of Bursaria and many other uni cellular forms.

Starvation is a frequent cause of dedifferentiation. The mon Hydra, by this and other means, may be made to lose all its tentacles, and eventually vert to a mere spheroid with no mouth, and similar phenomena have been described in anemones. The common fish Aurelia, kept without food, shrinks enormously in bulk, some parts, e.g., the gelatinous bell, being much more reduced than others like the mouth-tentacles ; specialized tissues lose their histological differentiation, e.g., the genital organs and the special sense-organs, the tentaculocysts. In the worm Ophryotrocha, remarkable dedifferentiation occurs if it is damaged or mutilated. In starvation, there will clearly be a "struggle of the parts," the less resistant breaking down and serving as food for the rest. Starvation itself is apparently favourable to dedifferentiation, but when this has once begun, the tissue can be more readily made to degenerate into mere food-materials. This differential ance of tissues has sometimes been turned to physiological ac count in higher forms, e.g., the salmon's sexual organs grow enormously while the fish is in fresh water, though it takes no or negligible food during this time. The necessary material is supplied by the dedifferentiation and later degeneration of the muscles. Similarly the wing-muscles of the queen ant are so constructed that when she breaks off her wings after the nuptial flight, they dedifferentiate, even tually becoming converted into food-material.

Dedifferentiation is often com plicated by resorption. When the process has reached a certain stage, many kinds of cell migrate out of the tissues. In higher forms with massive tissues this is not possible, and resorption is usually effected by phagocytes devouring the dedifferentiating cells. This is so in the tail resorption of metamorphosing tadpoles; the tissues begin to de differentiate, but are subsequently attacked by phagocytes.

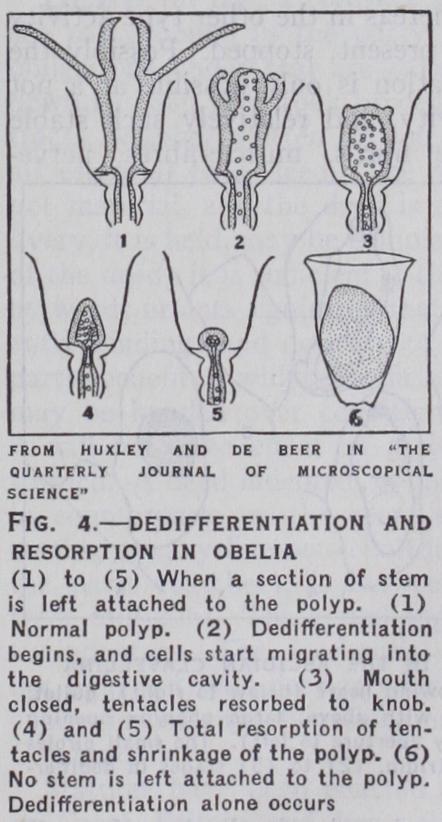

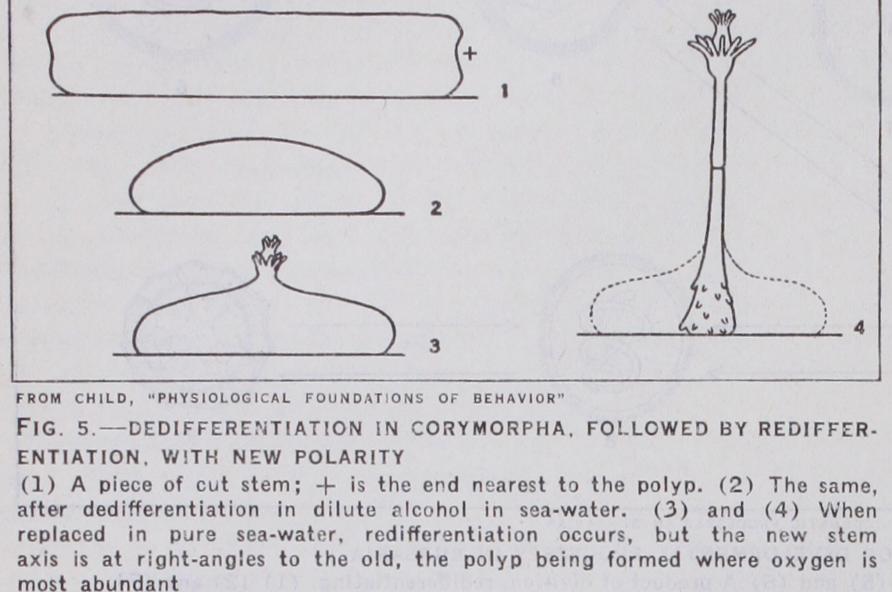

In lower types, the fate of differentiating organs is largely determined by the space able to the emigrating cells, e.g., in colonial Hydroids, such as Obelia, when exposed to favourable conditions, the polyps start to dedifferentiate as does Hydra; but the large spaces of the less susceptible stalk are able for the cells migrating out of the tissues, and accordingly the polyps become entirely resorbed into the stem. The same is true in the social Ascidian Perophora. In both cases the amount of stalk or stolon left attached to an individual (zooid) determines the final result. If the amount of stalk is relatively large, total sorption occurs. If small, the result is a dedifferentiated zooid. One particularly interesting point has been elicited by Child. By applying depressant agents such as weak alcohol to pieces of Hydroid stems (Corymorpha) he obtained dedifferentiation which led to complete obliteration of the original polarity. On being replaced in sea water, regeneration took place, but at right angles to the direction it would have taken if no dedifferen tiation had occurred.

The Ascidians are the most highly organized animals in which total dedifferentiation is possible. This has been best worked out in Clavellina. Halved animals may, in the midst of normal regeneration, dedifferentiate to a small opaque spheroid, from which later a whole organism may arise. Intact whole animals, if small, may also dedifferentiate thus. Dedifferentiation may be in duced by leaving in unchanged water, redifferentiation by change of water. Two successive dedifferentiations, each followed by re differentiation, have been obtained in a single animal, though de prived of food throughout. The internal organs become greatly simplified, and different parts are affected at a very different rate ; the cells revert to an em bryonic type. Recovery is not possible from the most extreme stages, but at all earlier stages the process is reversible.

Schultz has attempted to show that dedifferentiation is a true reversal of normal development ; but later work shows that this view is untenable. The struc tural changes seen are mainly due to the cells reverting to the "em bryonic" type, roughly cubical when in epithelia, spherical when isolated. This, however, is not due to any mysterious force compelling return to the embry onic type because it is embry onic, but because this type has the least amount of surface rela tive to volume ; to maintain any other form demands a continual performance of work against the forces of surface-tension, which is beyond the powers of cells ex posed to other unfavourable conditions. The picture is compli cated by two other factors—first, the facility with which different kinds of cells migrate out of their tissues ; secondly, the different resistance of cells, leading to the least resistant breaking down and becoming food-material for the others.

Behaviour which may perhaps be included under dedifferen tiation is that of (e.g.) certain Planarian flatworms when starved.

These do not revert to a morphologically simpler state, but be come smaller, living upon their own capital. As Child showed, these reduced specimens not only acquire the proportions of nor mal young animals, but are in most respects physiologically young; they have undergone rejuvenation (q.v.). Here the de struction of reserves and the altered surface-volume relations probably effect the change automatically.

Sea-urchin larvae dedifferentiate readily in unfavourable con ditions, resorbing arms and skeleton, and eventually becoming mouthless lumps. This tendency has been taken advantage of in nature, and dedifferentiation of larval tissues, followed by their resorption into the adult rudiment, is the method of normal metamorphosis (q.v.).

A striking type of dedifferentiation is that of tumour tissue, malignant and otherwise. When a tumour is formed, the cells of the tissue from which it arises lose some of their differentia tion. Roughly speaking, the greater the malignancy, the more complete the dedifferentiation. (See CANCER.) This type of dedifferentiation apparently differs importantly from that hither to discussed, for tumour-cells are characterized by undue ac tivity and multiplicative power, whereas in the other type activity is reduced, and multiplication, if present, stopped. Possibly the existence of histological differentiation is only possible at a not too high level of metabolic activity, and relatively such stable scaffoldings as connective tissue fibrils, muscle-fibres, nerve fibrils, etc., are only constructed and maintained when the cell's activities are keyed at a certain pitch, and are broken down when they are higher; just as, to use a rough analogy, sandbanks are only laid down in a river when its rate of flow is suitable, and are destroyed if its speed increases. On the principle of the struggle of the parts, it would be expected further that if cell metabolism were altered so as to encourage cell reproduction, less food-material would be available for maintaining structural dif ferentiation or for activities such as secretion. However, these views, though interesting, are admittedly speculative. They do not in any case cover all the facts, since differentiation can be shown to be sometimes caused by presumably chemical stimuli from another kind of tissue, e.g., when kidney-tubule tissue is cultivated alone in artificial media (see TISSUE-CULTURE) its cells dedifferentiate entirely; but when connective tissue is added, the tubule-cells differentiate to form regular tubules.

In any event, it is a well-established fact that active cell-multi plication is incompatible with the maintenance of differentiation; we may accordingly correlate the dedifferentiation of cancer cells with this fact, and conclude that its origin is different from the dedifferentiation correlated with lowered activity.

Dedifferentiation associated with increased cell-multiplication is also seen in regeneration. In many cases, the first process ob served at the cut surface after wound-healing is rapid multiplica tion of cells to form a so-called regeneration blastema, consisting of cells dedifferentiated as far as visible characteristics go. That they are also dedifferentiated in other respects is shown by the interesting results obtained in newts, where grafting of a young regeneration blastema, e.g., of a limb, to some other region, e.g., the newly-cut stump of the tail, will cause the blastema to com plete the organ on to which it is grafted, instead of that by which it was first regenerated. (See RE