Delhi

DELHI (deli), old capital of the Mogul empire in India, and the new capital of British India, lies on the right bank of the Jumna, practically in the same latitude as the more ancient cities of Cairo and Canton. Since the headquarters of the government of India was transferred from Calcutta to Delhi in 1912, the district around Delhi, formerly a part of the Punjab, has for administra tive reasons been constituted a minor province under a chief commissioner who is directly subordinate to the central govern ment. The ruins of several of the older fortresses (for they were all heavily walled) strew the surrounding country.

Two of them are of special interest :—Old Delhi (about io m. from the present city), where stand the stately Kutb Minar with the enigmatic Iron Pillar, and Tughlakabad with its titanic walls; but there is hardly an acre in all the intervening country that does not carry some relic of the historic past. The present city, the seventh of the series, was re-constructed by the emperor Shahjahan on an older site, and is still known locally as Shahjahanabad. The greater part of it is still confined within his walls. Of its river frontage, about 2i m. long, one third is occupied by the battlements of his palace; and the complete circuit of the walls is 51 miles. Shahjahan's original fortifications were strengthened by the British by the addition of a ditch and glacis, after Delhi was captured by Lord Lake in 1803 ; and its strength was turned against the British at the time of the Mutiny.

The Imperial Palace

(1638-48), now known as the "Fort," is disfigured by bare and ugly British barracks, among which are scattered exquisite gems of oriental architecture. The two most famous among its buildings are the Diwan-i-Am or Hall of Public Audience, and the Diwan-i-Khas or Hall of Private Audience. The Diwan-i-Am is a splendid building in the Hindu style, with 6o pillars of red sandstone supporting a flat roof. It was in the recess in the back wall of this hall that the famous Peacock Throne used to stand, "so called from its having the figures of two peacocks standing behind it, their tails being ex panded and the whole so inlaid with sapphires, rubies, emeralds, pearls and other precious stones of appropriate colours as to represent life." Tavernier, the French jeweller, who saw Delhi in 1665, describes the throne as of the shape of a bed, supported by f our golden feet, 20 to 25 in. high, from the bars above which rose 12 columns to support the canopy ; the bars were decorated with crosses of rubies and emeralds, and also with diamonds and pearls, while the columns had rows of splendid pearls. The whole was valued at f6,000,000. This throne was carried off by the Persian invader Nadir Shah in 1739, and has been rumoured to exist still in the Treasure House of the Shah of Persia; but Lord Curzon, who examined the thrones there, found nothing except perhaps some portions worked up in a modern Persian throne.

The Diwan-i-Khas is smaller than the Diwan-i-Am, and con• sists of a pavilion of white marble, in the interior of which the art of the Moguls reached the perfection of its jewel-like decora tion. On a marble platform rises a marble pavilion, the flat-coned roof of which is supported on a double row of marble pillars. The inner face of the arches, with the spandrils and the pilasters which support them, are covered with flowers and foliage of delicate design and dainty execution, crusted in green serpentine, blue lapis lazuli and red and purple porphyry; the ravages of time were repaired as far as possible by Lord Curzon.

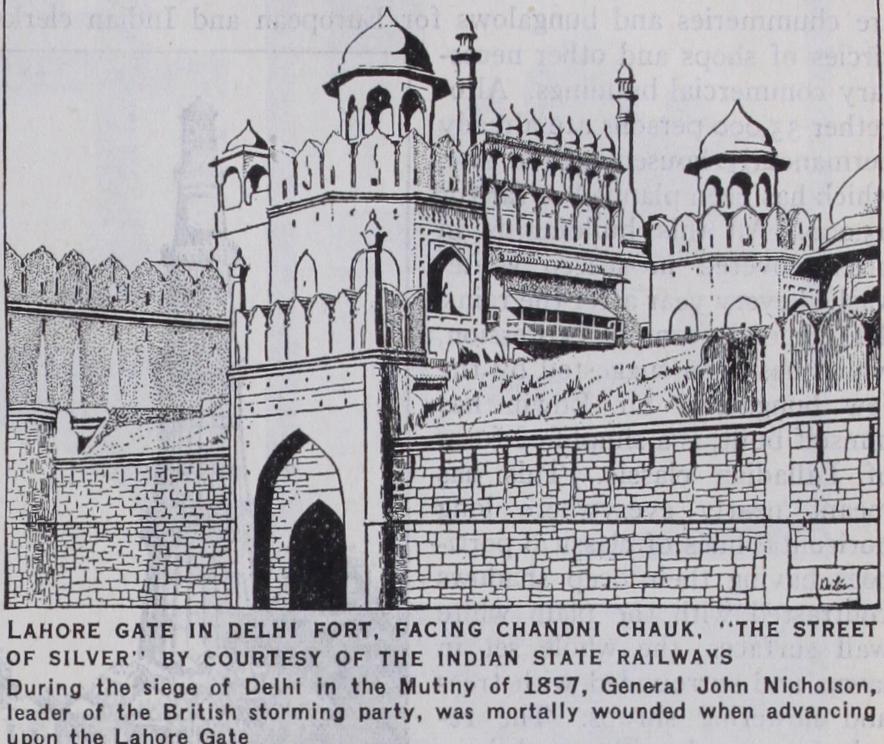

The Chandni Chauk

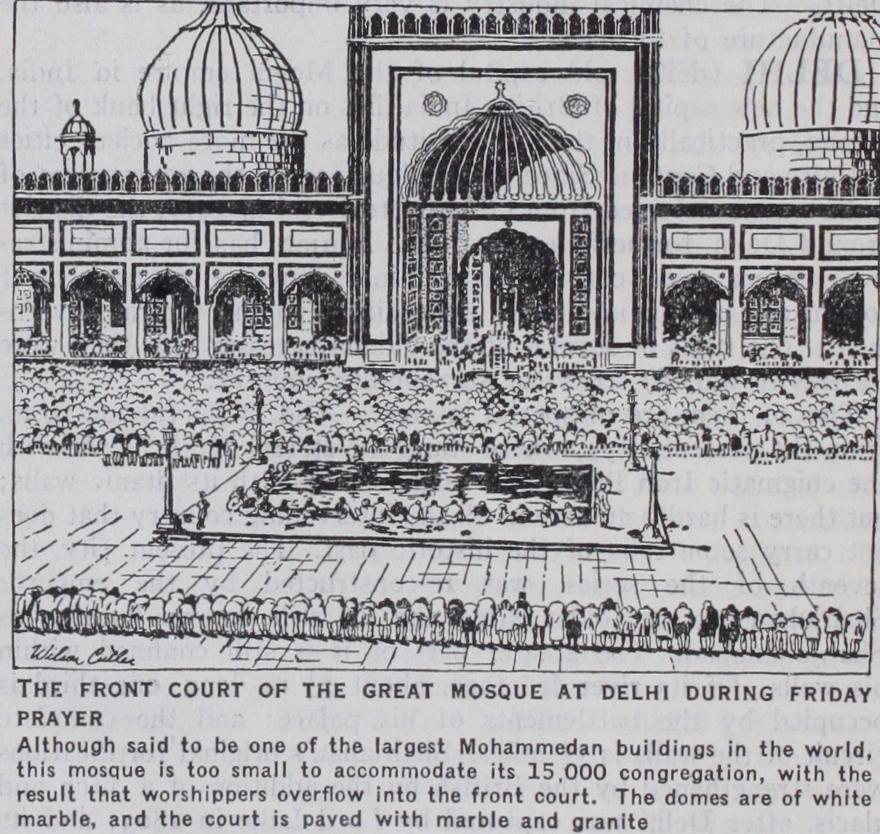

("silver street"), which was once sup posed to be the richest street in the world, has fallen from its high estate, though it is still a broad and imposing avenue with a double row of trees running down the centre. During the course of its history it was four times sacked, by Nadir Shah, Timur, Ahmad Shah and the Mahrattas, and its roadway has many times run with blood. The jewellers and ivory-workers now dwell there.A short distance south of the Chandni Chauk the Jamma Musjid, or Great Mosque, rises boldly from a small rocky emi nence. It was erected in 1648-5o, two years after the royal palace, by Shah Jahan. Its front court, 45o ft. square, and surrounded by a cloister open on both sides, is paved with granite inlaid with marble, and is approached by a magnificent flight of stone steps. The mosque itself is paved with marble, and three domes of white marble rise from its roof, with two tall minarets at the front corners. Two other mosques in Delhi deserve passing notice, the Kala Musjid or Black Mosque, which was built about 138o in the reign of Feroz Shah, and the Moti Musjid or Pearl Mosque, a tiny building added to the palace by Aurangzeb, as the emperor's private place of prayer.

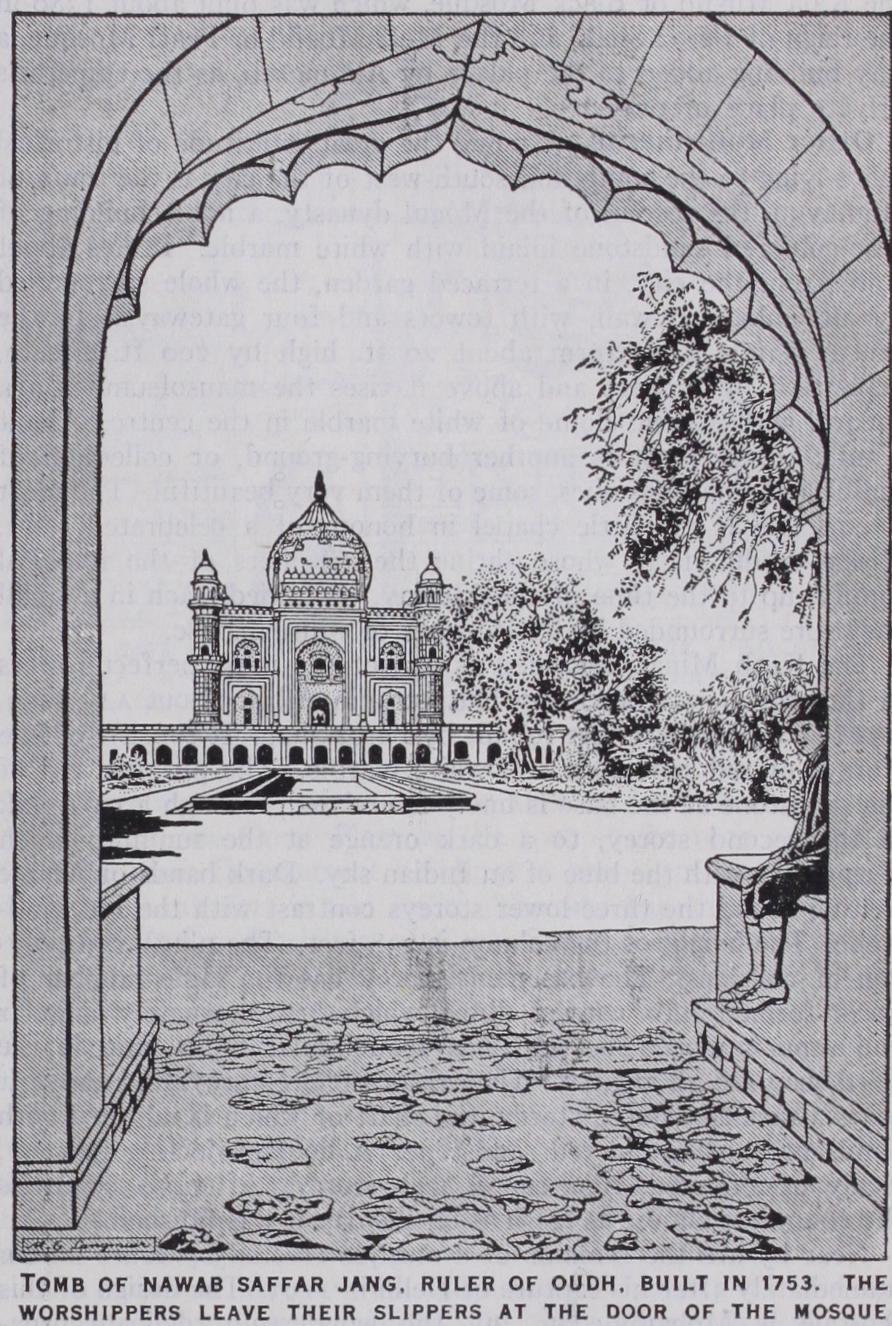

Other Monuments.—Among the great multitude of historical relics lying to the south and south-west of the city is the tomb of Humayun, the second of the Mogul dynasty, a noble building of rose-coloured sandstone inlaid with white marble. It lies about 3 m. from the city, in a terraced garden, the whole surrounded by an embattled wall, with towers and four gateways. In the centre stands a platform about 20 ft. high by 200 ft. square, supported by arches ; and above it rises the mausoleum, also a square, with a great dome of white marble in the centre. About a mile to the west is another burying-ground, or collection of tombs and small mosques, some of them very beautiful. The most remarkable is the little chapel in honour of a celebrated saint, Nizam-ud-din, near whose shrine the members of the imperial family, up to the time of the Mutiny, lie buried, each in a small enclosure surrounded by lattice-work of white marble.

The Kutb Minar, regarded as one of the most perfect towers in the world, was begun by Kutb-ud-din Aibak about A.D. 'zoo. The two top storeys were rebuilt by Feroz Shah. It consists of five storeys of red sandstone and white marble. The purplish red of the sandstone at the base is finely modulated, through a pale pink in the second storey, to a dark orange at the summit, which harmonizes with the blue of an Indian sky. Dark bands of Arabic writing round the three lower storeys contrast with the red sand stone. The height of the column is 238 feet. The plinth is a poly gon of 20 sides. The basement storey has the same number of faces formed into convex flutes which are alternately angular and semicircular. The next has semicircular flutes, and in the third they are all angular. Then rises a plain storey, and above it soars a partially fluted storey, the shaft of which is adorned with bands of marble and red sandstone. A bold projecting balcony, richly ornamented, runs round each storey. After six centuries the column is almost as fresh as on the day it was finished.

Near by are the remains of a mosque erected by Kutb-ud-din immediately after his capture of Delhi in i r 93. The design of this mosque is Mohammedan, but the wonderfully delicate orna mentation of its western façade and other remaining parts is Hindu. In the inner courtyard stands the Iron Pillar, dating from about A.D. 400. It consists of a solid shaft of wrought iron some 16 in. in diameter and 23 f t. 8 in. in height, with an inscription eulogizing Chandragupta Vikramaditya. It was brought here, possibly from Behar, by Anang Pal, a Rajput chief, who erected it in io52.

Modern Buildings include the temporary Vice-regal Lodge ; the old Residency, now occupied by a government high school; the Protestant church of St. James, built at a cost of f r o,000 by Colonel Skinner, an officer well known in the history of the East India Company; and the college and hospital of the Cambridge Mission. Behind the Chandni Chauk, to the north, lie the Queen's Gardens; beyond them the "civil lines" stretch away out to and along the well-known rocky ridge, about a mile outside the town. The old Delhi college, once famous as an oriental school, was attacked during the Mutiny, plundered of a very valuable oriental library, and the building completely destroyed.

The Ridge, famous as the British base during the siege of Delhi during the Mutiny, in 1857, is a last outcrop of the Aravalli hills which rises in a steep escarpment some 6o ft. above the city. At its nearest point on the right of the British position, where the Mutiny memorial now stands, the Ridge is only 1,200 yd. from the walls of Delhi ; at the Flagstaff tower in the centre of the position it is a mile and a half away; and at the left near the river nearly two miles and a half. It was behind the Ridge at this point that the main portion of the British camp was pitched. The gallant Nicholson was buried just outside the Kashmir gate, near to where his statue now stands. The Kashmir gate itself bears a slab recording the gallant deed of the party under Lieutenants D. C. Home and P. Salkeld, who blew in the gate in broad day light on the day that Delhi was taken by assault.

The Population of Delhi according to the census of 193i was of whom 18o,o18 were Mohammedans. The city is the converging point of a number of railways and occupies a central position, being 94o m. from Karachi, 95o from Calcutta, and 96o from Bombay. Owing to the advantages it enjoys as a trade centre, Delhi is recovering much of the prominence which it lost at the time of the Mutiny. It has a number of busy fac tories, and famous hand industries in gold and silver filigree work and embroidery, jewellery, muslins, shawls, glazed pottery and wood-carving.

The Province of Delhi has an area of 573 sq.m. and a popula tion of 636,246. It consists of a strip of territory on the Jumna river which formed part of the old Delhi district, and of 65 villages on the opposite bank which were formerly in the Meerut district of the United Provinces. It is an enclosure created for administrative convenience, as a consequence of the new capital.

When Lord Lake broke the Mahratta power in 18o3, and the emperor was taken under the protection of the East India Com pany, the districts of Delhi and Hissar were assigned for the main tenance of the royal family, and were administered by a British resident. In 1832 the office of resident was abolished, and the tract was annexed to the North-Western Provinces. After the Mutiny in 1858 it was separated from the North-Western Prov inces and annexed to the Punjab. The old Division of Delhi has its headquarters now at Ambala. (ME. ; X.) History.—According to legend Delhi has from time im memorial been the site of a capital city. The actual history of Delhi, however, dates no further back than the i i th century A.D., when Anangapala (Anang Pal), a chief of the Tomara clan, built the Red Fort, in which the Kutb Minar now stands; in 1 o5 2 the same chief removed the famous Iron Pillar from its original position, probably at Muttra, and set it up among a group of temples of which the materials were afterwards used by the Muslims for the construction of the great Kutb Mosque. About the middle of the i 2th century the Tomara dynasty was over thrown by Vigraha-raja, the Chauhan king of Ajmere. His nephew and successor was Prithwi-raja, the last Hindu ruler of Delhi. In I191 came the invasion of Mohammed of Ghor. De feated on this occasion, Mohammed returned two years later, overthrew the Hindus, and captured and put to death Prithwi raja. Delhi became henceforth the capital of the Mohammedan Indian empire, Kutb-ud-din (the general and slave of Mohammed of Ghor) being left in command. The dynasty retained the throne till 129o, when it was subverted by Jalal-ud-din Khilji. The house of Khilji came to an end in 1321, and was followed by that of Tughlak ; Ghias-ud-din Tughlak erected a new capital about 4 m. farther to the east, which he called Tughlakabad. The ruins of his fort remain. Ghias-ud-din was succeeded by his son Mo hammed b. Tughlak, who reigned from 1325 to 1351. Under this monarch the Delhi of the Tughlak dynasty attained its utmost growth. His successor Feroz Shah Tughlak transferred the capital to a new town, Ferozabad, which he founded some miles away. In 1398, during the reign of Mahmud Tughlak, occurred the Tatar invasion of Timurlane. The king fled to Gujarat, his army was defeated under the walls of Delhi, and the city surrendered. At length' Mahmud Tughlak regained a fragment of his former king dom, but on his death in 1412 the family became extinct. He was succeeded by the Sayyid dynasty, which held Delhi and a few miles of surrounding territory till 1444, when the house of Lodi supervened and Agra became the capital. In 1526 Baber, sixth in descent from Timurlane, invaded India, defeated and killed Ibra him Lodi at the battle of Panipat, entered Delhi, was proclaimed emperor, and finally put an end to the Afghan empire. Baber's capital was at Agra, but his son and successor, Humayun, removed it to Delhi. In 154o Humayun was defeated and expelled by Sher Shah, who entirely rebuilt the city, enclosing and fortifying it with a new wall. In 1555 Humayun, with the assistance of Persia, regained the throne; but he died within six months, and was suc ceeded by his son, the illustrious Akbar.

During Akbar's reign and that of his son Jahangir, the capital was either at Agra or at Lahore, and Delhi once more fell into decay. Between 1638 and 1658, however, Shah Jahan rebuilt it. In i7o7 came the decline. Insurrections and civil wars on the part of the Hindu tributary chiefs, Sikhs and Mahrattas broke out. Aurungzeb's grandson, Jahandar Shah, was, in 1713, de posed and strangled after a reign of one year ; and Farrakhsiyyar, the next in succession, met with the same fate in 1719. He was succeeded by Mohammed Shah, in whose reign the Mahratta forces first made their appearance before the gates of Delhi, in 1736. Three years later the Persian monarch, Nadir Shah, after defeating the Mogul army at Karnal, entered Delhi in triumph. For fifty-eight days Nadir Shah remained in Delhi, and when he left he carried with him great treasure.

In 1771 Shah Alam, the son of Alamgir II., was nominally raised to the throne by the Mahrattas, the real sovereignty resting with the Mahratta chief, Sindhia. An attempt of the puppet emperor to shake himself clear of the Mahrattas, in which he was defeated in 1788, led to a permanent Mahratta garrison being stationed at Delhi. From this date, the king remained a cipher in the hands of Sindhia, until thd 8th of September 1803, when Lord Lake overthrew the Mahrattas under the walls of Delhi, entered the city, and took the king under the protection of the British. Delhi, once more attacked by a Mahratta army under the Mahratta chief Holkar in 18o4, was gallantly defended by Colonel Ochterlony, the British resident, who held out against overwhelm ing odds for eight days, until relieved by Lord Lake, and the city, together with the Delhi territory, passed under British ad ministration.

Fifty-three years of quiet prosperity for Delhi were brought to a close by the Mutiny of 1857 (see INDIA, History). It was not till the 2oth of September that the entire city and palace were occupied, and the reconquest of Delhi was complete. Dur ing the siege, the British force sustained a loss of 1,012 officers and men killed, and 3,837 wounded. On receiving a promise that his life would be spared, the last of the house of Timur surrendered to Major Hodson; he was afterwards banished to Rangoon. Delhi, thus reconquered, remained for some months under military authority. Delhi was made over to the civil authorities in January 1858, but it was not till 1861 that the civil courts were regularly reopened. Since that date Delhi has settled down into a prosperous commercial town, and a great railway centre. Delhi was selected for the scene of the Imperial Proclama tion on the ist of January 1877, and for the great Durbar held in January 1903 for the proclamation of King Edward VII. as emperor of India.

New Delhi.—New Delhi, the establishment of which was first announced by His Majesty King George V. at the Imperial Durbar of 191i in the second year of the Viceroyalty of Lord Hardinge, has been designed and built as a capital for all India. Its site, occupying at present about 5 sq.m., is on the great alluvial plain of the Jumna sloping slightly from west to east. Its centre in the Great Place at the foot of the rock on which stand the main Government buildings is about 5m. to the south of Shah Jahan's fort in Old Delhi. The site was chosen in 1912 by a commission consisting of Capt. Swinton (Chairman), Mr. Brodie, engineer to the City of Liverpool and Mr. Edwin (now Sir Edwin) Lutyens, architect. To the last of the three was given the planning of the city, after an agreement had been come to with Lord Hardinge that the main Government buildings should be placed on the rock to which reference has already been made. This rock is a spur of the main Delhi ridge of Mutiny fame and like it consists of very hard quartzite. It stood some 5oft. above the plain but the top 2oft. have been blasted off to make a level plateau for the great buildings and to fill in depressions.

With this low acropolis as the focus of his city Sir Edwin Lutyens laid out a very original city plan as large in scale and covering a larger area of organized planning than Washington (D.C.). His central mall and his diagonal avenues may owe some thing to L'Enfant's plan for that city as well as something to Sir Christopher Wren's plan for London after the Great Fire, but the total result is quite different.

It is a plan based on a series of large hexagons closed by a semi circular road to the west where the site is bounded by the ridge. This plan, with its wide central processional road and its diagonals at 3o° and 6o°, brings into vista all the chief landmarks of the flat landscape. The main axis leads to the old walled city of Indrapat, while one avenue is focussed on the great mosque or Jumma Musjid in Old Delhi, forming an absolutely direct route to that town, and another on the lofty tomb of the em peror Humayun. Subsidiary avenues lead to other monuments. In this way the new city is not only related to the Delhis of the past which surround it but emphasizes its peaceful and all-em bracing character in distinction to their encircling walls and forti fications. In detailed planning the roads are in three classes, i5oft., i2oft. and 76ft. wide, lined with one, two or even three avenues of trees. The central mall has continuous canals of water as well. Where main roads intersect there are great round turning points showing an appreciation in the plan of the needs of motor traffic several years before that traffic had anywhere developed.

The filling in of the plan has provided sites of varying im portance for every class of residence. The princes of India are to build their palaces in the great circular roads round the triumphal arch to the Indian armies which closes the main pro cessional way. H.H. the nizam of Hyderabad has already com pleted a large palace with the advice of Sir Edwin. Along the main axis are sites for Government buildings—the Record Office by Sir Edwin Lutyens is partially built—and for the residences of members of council. Along the lesser avenues are residences for officials of various grades and nationality, hostels for mem bers of the assembly divided in like manner. In other districts are chummeries and bungalows for European and Indian clerks, circles of shops and other neces sary commercial buildings. Alto gether 3 5,00o persons are already permanently housed on the site, which has been planned so far for 65,000. All this building is in brick covered in stucco white washed every year after the rains.

The general form of expression, which has been suggested by the few bungalows Sir Edwin has himself built, is a simplified form of Palladian classic. This has meant nearly everywhere long horizontal lines of classical porti coes having their deep shadows contrasted with the plain white wall surfaces, the whole set in lawns and surrounded with trees and flowering shrubs. The re sult is a garden city and in a more just sense than the term is generally used. Seen from the ridge the city is already a sea of trees (all of which have had to be planted and have water-pipes laid to them), through which long, low, white classical build ings glint.

It remains to mention the main buildings on the acropolis of rock which form the climax of the town and overlook the plain of bungalows, trees and magnificent roads, very much as the Palace of the Popes does the plain of Avignon. These are three, the two great secretariat buildings designed by Sir Herbert Baker which line the processional way, and Government House, the palace of the viceroy, designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, to which this great avenue leads. As an afterthought, there is also the big legisla tive building. It is situated on the plain at the foot of the rock on the axis of the road from Old Delhi and is a great circular structure by Sir Herbert Baker with a continuous open colonnade, half a mile in circumference. It contains the three chambers, one for the assembly, one for the council and one for the ruling princes grouped round a central library large enough to hold a durbar of the members of all three. Its circular form was dictated partly by political reasons and partly by the triangular space on which it is situated between three roads. It is hoped that some day a circular structure on a similar triangular site on the opposite side of the main axis may house supreme courts of justice for all India.

The two secretariat buildings are in the main Italian structures and present to the processional way four projecting blocks in pairs each carrying a portico of columns with recessed courts between. The idea of these projections is apparently to stand out like sentinels on the great approach. Crowning the recessed building in the centre on either side is a tall Italian dome on a drum. All these features, if not too tall and important in them selves, together with the towers which rise from the end blocks and face down the canal, being in pairs about the main axis should make a fine approach to the great palace set back behind its forecourt and itself crowned with a great dome. This latter build ing is (early 1928), two years from completion and though enough has been built to show that it is a true palace of great majesty and refinement with many noble courts, stairways and apartments, as well as a great durbar hall under its dome, it yet remains to be seen whether the secretariat buildings are not too lofty for full justice to be done to it. All these four great buildings, together with their steps, terraces and surrounding walls, are in red sand stone to the base of the columns and in white above, brought by a specially constructed railway from the States of Bharatpur and Dholpur, 8om. away. Two to three thousand masons have been employed continually on the work. The form of architec tural expression used throughout is Palladian classic but both architects have introduced Indian features such as the Chajja or projecting stone slab to keep walls cool, the Chattri or um brella shaped roof—Indian symbol of royalty—the Jaalis or pierced stone grilles. Sir Edwin Lutyens, however, in Govern ment House, has deliberately gone farther than Sir Herbert Baker in the secretariat buildings in trying to marry the spirit of Indian Architecture, both Hindu and Mohammedan, to that of English and Italian classic. Because the spirit of Indian detail as far as compatible with classical motives has been absorbed by him rather than its forms copied, new and interesting character, which never theless seems harmonious and inevitable, has resulted.

(C. H. R.)