Democratic Party

DEMOCRATIC PARTY, founded by Thomas Jefferson, the third president, the oldest continuously existing political instrumentality in the United States. Though up to 1929, it had since the Civil War been successful in but four Presidential elec tions, for more than half the 14o years since the first President was chosen it directed the destinies of the nation, and even when out of office has not been altogether out of power. Its original name was the Republican Party and the day of its birth has been definitely fixed as May 13, 1792, that being the date of a letter from Jefferson to Washington in which is made the first authori tative claim of a name for the party of which the former had become the recognized head. Actually the seeds were sown in the constitutional convention of 1787, when the first battles were fought between those who wanted a strong, centralized, federal government and those who wanted the least possible federal gov ernment consistent with national security. In the debates of that convention can be located the Democratic germ plasm, the ultimate growth of which under Jefferson's genius was the es tablishment of a party whose theory aimed at direct popular control over the government; which championed the rights of the masses and was really democratic in theory and in fact ; which was based on the fundamental belief that the people are capable of governing themselves ; which aimed at the widest possible ex tension of the suffrage and the fullest measure of personal lib erty consistent with law, order and the national welfare; which was against all sumptuary laws ; which favoured the strictest interpretation of the constitution and the conservation of the rights of the States; which opposed the centralization of power in the Federal Government ; which believed in equal rights for all, special privileges for none, and stood militantly for religious liberty, free speech and a free press.

Though this new party was an organized and militant force in Congress in 1792 it was not until 1800 that it secured control of the government with the triumphant election of Jefferson as president and the complete rout of the Federalists under Alex ander Hamilton, who typified the other political point of view as completely as Jefferson did the democratic. For 40 years from the first election of Jefferson the Democratic Party was in continuous control of the government, during most of that time almost without opposition. In 184o it lost to the Whigs but through the death of President William Henry Harrison, Tyler succeeded to the presidency and became more of a Democrat than Whig. It regained control in 1844, lost in 1848, came back into power in 1852 and remained in until its historic split or the slavery rock in 186o, followed so quickly by the Civil War. It may therefore be said that with the exception of four years the Democratic Party was in practically complete control of the gov ernment from 1800 to 186o. During the first quarter of a cen tury it was almost completely dominated by Thomas Jefferson, its founder. In his first inaugural address he beautifully enunciated its fundamental concepts and principles, most of which have years ago become embedded into the political institutions of the country, accepted by politicians and public men regardless of party. Jefferson, after serving two terms, selected as his successor, perhaps his closest friend, James Madison, and was chiefly instrumental in making James Monroe, undoubtedly his next closest friend and political disciple, the successor of Madison.

Though Jefferson founded the party on the principle of popu lar government and his influence and power as party leader lasted longer than that of any other individual in the country before or since, it was not until 1828 that the people really came into power, that the party became democratic in fact as well as in theory. With the election of Andrew Jackson, the second tower ing figure in Democratic party history, the people really took over the government which had up to that time been practically held in trust for them by leaders such as Jefferson and Madison, who, while democratic in political thought, were as individuals aristocratic in birth, breeding and environment. They believed in popular government but it was Jackson who really put it into effect. It is also true that beginning with Jefferson, each Demo cratic president of his period found it essential to depart from the strict construction principles of the party, the first instance of which was the acquisition of Louisiana, an undoubtedly wise and popular step, but one for which there was in fact no con stitutional warrant. It has since that day been a not infrequent habit of the Democratic Party to repudiate at least one of its basic principles—local self-government or State's rights—and to this fact is traceable no small part of its troubles. Under Jack son, however, it swung back to its original strict construction basis. Under Jackson for the first time the people really participated in politics generally. By this time the restrictions surrounding the suffrage had been largely removed, and it was the mass sentiment favouring Jackson that swept him into power. Under Jackson for the first time the politicians began really to reach the people and to play to public sentiment. Under hirn the first real politi cal machine was constructed with, for the first time, what has been called "the spoils system," by which the federal offices were distributed as a reward for party service. Though his power did not last as long, Jackson was during his two terms as com pletely the leader of his party as was Jefferson and long after he went out of office he remained a popular idol. He was not only the champion of the common people but he was one of them. His administrations were tempestuous and the party battles in which he engaged dramatic and bitter. The two great fights of his career as president, both of which he won, were, first, that to abolish the second United States Bank, and second, to crush the defiance of the Federal Government by South Carolina, where, under the leadership of his arch enemy, John C. Calhoun, resent ment over the tariff laws led to a seditious effort to make the nullification issue a real national menace. Jackson's Nullification Proclamation, which broke the nullification movement had a ring and a fervour such as no other defence of the Union has con tained. It is one of the country's imperishable documents which, like the Monroe Doctrine, the Democratic Party treasures as having been given to the nation by a Democratic President. It should be mentioned here that it was not until after Jackson's election in 1828 that the party name really changed from Repub lican to Democratic. During the Jackson campaign his followers began to call themselves Democrats and by his second election the name was in general use.

Between 1836 when Jackson, then an old man, retired, and 186o, though there were four Democratic presidents—Van Buren, selected by Jackson, Polk, the first "dark horse," Pierce and Buchanan—the real Party story is the story of its futile struggles to avoid by ignoring it, the slavery issue, and of the inevitability of the great smash which so badly wrecked the party that it was 24 years before it again elected a president. After the Van Buren administration the party more than ever became dominated by the South, which was unshakably convinced that its economic and social as well as political interests were bound up in the preserva tion of slavery. The fight of the South was for the extension of slavery into new territory as the one way of retaining its political importance and avoiding being overwhelmed by the great indus trial States of the North and West. To further this end, the Demo cratic Party, under compulsion from the South, repudiated its basic principle. It insisted upon the broadest possible construc tion of the Constitution in order to force slavery on the new States or territories and then applied to them the most rigid possible State's rights doctrine in order to preserve slavery from constitutional interference. By 185o the slavery issue had ad vanced too far to permit again any such tacit agreement not to discuss it as had obtained for so many years following the Missouri Compromise. The effort was, however, made in the Compromise of 1850, proposed by Henry Clay and accepted by the Whigs as well as the Democrats, and in both the 1852 and 1856 Democratic national conventions the stand was taken that the issue had been settled. But that idea was absurd. However com pletely the political parties might ignore it in their platforms, the one absorbing question in the country was the slavery ques tion. The final crash came in 186o. When the delegates to the Democratic convention of that year assembled in Charleston, S.C., on April 23, they were in a highly emotional state. The fight came over the platform. The majority report of the resolutions committee setting forth the point of view of the South was as follows : "Resolved.—That the government of a Territory organized by an act of Congress is provisional and temporary; and during its existence, all citizens of the United States have an equal right to settle with their property in the Territory, without their rights, either of person or of property, being destroyed or impaired by congressional legislation.

"2. That it is the duty of the Federal Government, in all its departments, to protect, when necessary, the rights of persons and property in the Territories, and wherever else its constitu tional authority extends.

"3. That when the settlers in a Territory, having an adequate population, form a State constitution, the right of sovereignty commences, and, being consummated by admission into the Union, they stand on an equal footing with the people of other States; and the State thus organized ought to be admitted into the Federal Union, whether its Constitution prohibits or recognizes the in stitution of slavery." These resolutions were vital to the Southern delegates. When the convention, dominated by Douglas delegates, rejected these resolutions and adopted a minority report ignoring any specific slavery declaration, half the Southern delegates bolted the con vention. Eventually, after adjournment and reassembling in Baltimore, Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois was nominated for president by the Northern wing, left in complete control. The bolters finally met in Richmond, adopted the rejected majority report as a platform and nominated John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky and Joseph Lane of Oregon by unanimous vote. Thus stood the party, wrecked, ruined, exhausted by internal struggle over a great moral issue and foredoomed to defeat. The newly formed Republican Party with its clear-cut stand against the extension of slavery, won its first great victory.

Though Lincoln did not get a majority of the popular vote he received a great majority in the electoral college, and the Democrats not only lost the presidency but control of Congress as well.

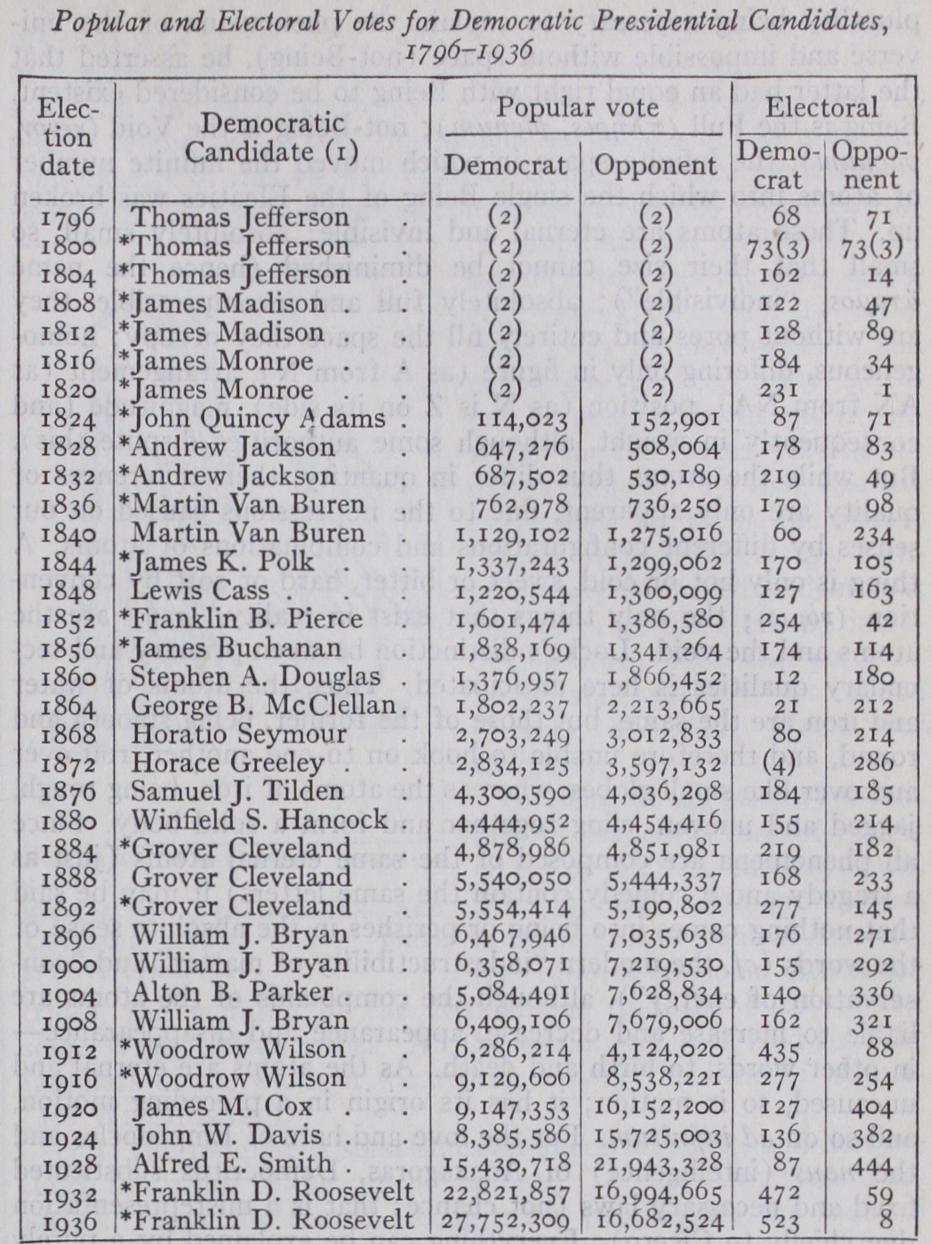

From 186o to 1936 the Democratic Party has been in power only 20 years—in complete control of Congress about half that time. With the Civil War it changed from the majority into the minority party and in the 76 years from 186o to 1936 it has been defeated 14 times in presidential contests, successful five. One of these defeats—that of Samuel J. Tilden in 1876—it is true was not really a defeat but a victory, though the party was de prived of its fruits. The enfranchisement of the negro that fol lowed the war did two things to the Democratic Party—first, it made the South unshakably Democratic; second, it gave to the Republicans an advantage in every pivotal State outside of the South in which there was a negro population. It was not until 1884 that the Democrats regained control of the government with the election of Grover Cleveland. They lost with him in 1888, but renominated and elected him again in 1892. In 1896 the party once more split disastrously—this time on the free silver rock, and its candidate—William Jennings Bryan—was overwhelmingly defeated. Through their addiction to economic heresies under the Bryan leadership the Democrats after 1896 became even more definitely the minority party, and the natural tendency of the large business interests to support the Republican ticket in na tional elections was strengthened. Democratic success in 1912 was due to three things—the Taft-Roosevelt feud in the Repub lican party; the final loosing of the Bryan grip; and the strong appeal of the Woodrow Wilson candidacy. Beyond question the two Wilson administrations stand out in Democratic history as most eventful and extraordinary. In the first administration more genuinely constructive legislation, starting with the Fed eral Reserve Act, was enacted than in any previous four-year period, while in the second, under Democratic leadership, the country successfully participated in the greatest of all wars. What most redounds to the credit of the Democratic Party was that despite the inevitable waste and blunders inseparable from such a conflict, there was a complete absence of any wholesale political plundering or governmental graft such as had character ized previous wars. The most rigid probe of the Republicans following the war failed to reveal any thievery not of a trivial nature. From 192o to 1932 the party was out of office and for the most part out of power. It lacked unifying issues or leader ship and suffered a diminution of support from business and the press. The question of Prohibition split its ranks worse than those of the other side and the bitterness of religious bigotry poisoned its spirit. The backwash of the World War in 1920 and the tide of prosperity in 1924 and 1928 brought it crushing national defeats although in state politics its losses were less severe. 1932, however, saw a complete overturn. Aided on one hand by the natural reaction of the electorate to hard times, and on the other hand by the personal charm and adroit political leader ship of Franklin D. Roosevelt, their own candidate, the Demo cratic Party won a sweeping victory, carrying all but six states; in 1934 the drift was still to the Democratic Party; and in 1936 the Party's triumph was the greatest for a hundred years, all but two states, Maine and Vermont, casting their vote to Roose velt and Garner.

See Harold Rozelle Bruce, American Parties and Politics (1927) ; and Frank Richardson Kent, The Democratic Party (1928) ; Robert C. Brooks, Political Parties and Electoral Problems (1923) ; Arthur N. Holcombe, Political Parties of Today (1924) ; Charles E. Merriam, The American Party System (1922) ; J. P. Foley (ed.), The Jeffersonian Cyclopaedia (New York, 'goo) ; W. D. Jones, Mirror of Modern Democracy; History of the Democratic Party from r825 to (New York, 1864) ; R. H. Gillet, Democracy in the United States (New York, 1868) • (F. R. K.) *Elected.

1. Popularly called "Republicans" up to the time of Andrew Jackson.

2. Electors chosen by legislatures in many states.

3. Contest decided in H. of Rep. Jefferson elected.

4. Greeley died before electoral vote was cast.