Demonology

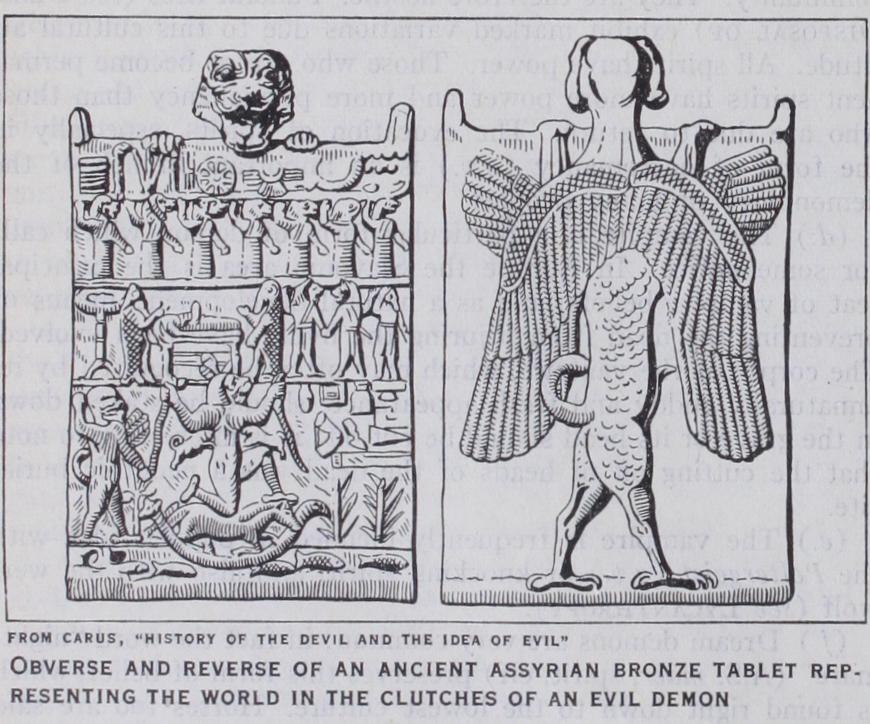

DEMONOLOGY, the branch of the science of religions which relates to superhuman beings which are not gods (Daiµwv, demon, genius, spirit). Demons, when regarded as spirits, may either be human, or non-human, separable souls, or discarnate spirits which have never inhabited a body; a sharp distinction is often drawn between these two classes which are frequently conceived as producing identical results, e.g., diseases.

The term includes (L) human souls regarded as genii or familiars, (2) such as receive a cult (for which see ANCESTOR WORSHIP), and (3) ghosts or other malevolent revenants; ex cluded are souls conceived as inhabiting another world. Demons may be regarded as corporeal, since primitive peoples do not distinguish clearly between material and immaterial beings.

Prevalence of Demons.

All the affairs of - life are supposed to be under the control of spirits, each ruling a certain element or even object, and themselves in subjection to a greater spirit. A rise in culture often results in an increase in the number of spiritual beings with whom man surrounds himself.

Character of Spiritual World.

The ascription of malev olence to the world of spirits is by no means universal. Local spirits are often regarded as inoffensive in the main; true, the passer-by must make some trifling offering as he nears their place of abode; but it is only occasionally that mischievous acts, such as the throwing down of a tree on a passer-by, are, in the view of the natives, perpetrated by the spirits. So, too, many of the spirits especially concerned with the operations of nature are conceived as neutral or even benevolent.

Classification.

Besides the distinctions of human and non human, hostile and friendly, the demons in which the lower races believe are classified by them according to function, each class with a distinctive name, with extraordinary minuteness.(a.) Natural causes, either of death or of disease, are hardly, if at all, recognized by the uncivilized ; everything is attributed to spirits or magical influence of some sort. The spirits which cause disease may be human or non—human; they may enter the body of the victim (see PossEssloN), and either dominate his mind as well as his body, inflict specific diseases, or cause pains of various sorts. The demon theory of disease is still attested by some of our medical terms; epilepsy (Gr. i7rL ntkcs, seizure) points to the belief that the patient is possessed. As a logical consequence of this view of disease the mode of treatment among peoples in the lower stages of culture is marked by an endeavour to propitiate the evil spirits by sacrifice, to expel them by spells, etc. (see EXORCISM), to drive them away by blowing, etc. ; and conversely to keep away small pox by placing thorns and brush wood in the paths leading to places afflicted by that disease, in the hope of making the disease demon retrace his steps. An other way in which a demon is held to cause disease is by intro ducing itself into the patient's body and sucking his blood (Rivers, Medicine, Magic and Religion) .

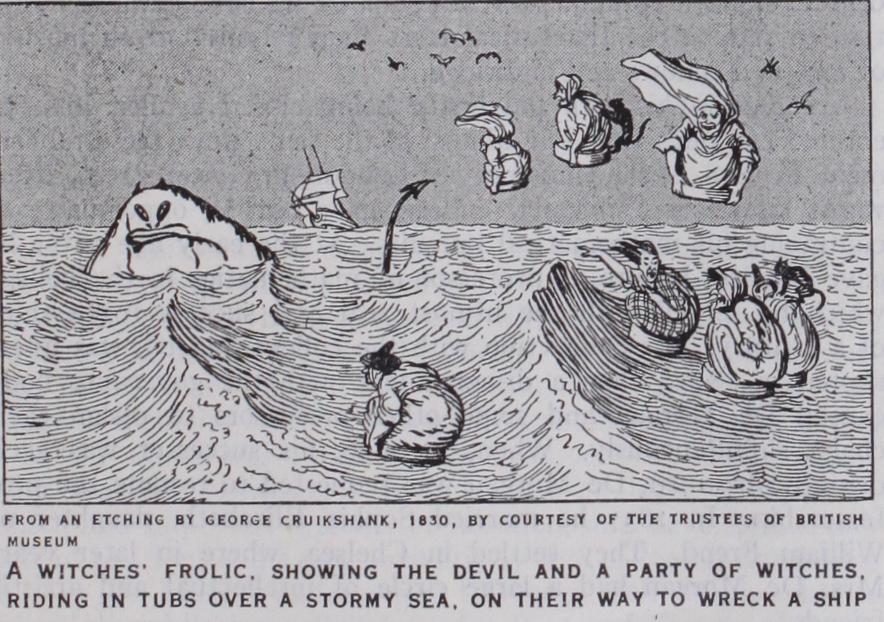

(b.) One of the primary ings of bacµwv is that of genius (q.v.) or familiar, tutelary spirit. The animal guardian appears in the nagual of Central America, the yunbeai of some Australian tribes, the inanitou of the Red Indian and the bush soul of some West African tribes. All the world over it is held that the familiars of the witch or wizard can assume the form of animals (see WITCHCRAFT).

(c.) The familiar is sometimes an ancestral spirit, and here we touch the fringe of the cult of the dead (see also ANCESTOR WOR SHIP). Especially feared among many peoples are the souls of those who have committed suicide or died a violent death ; the woman who dies in childbed is held to become a demon of the most dangerous kind; even the unburied, as restless, dissatisfied spirits, are more feared than ordinary ghosts. These are they who cannot be reborn and are permanently severed from their community. They are therefore hostile. Funeral rites (see DEAD, DISPOSAL, OF) exhibit marked variations due to this cultural at titude. All spirits have power. Those who are or become perma nent spirits have more power and more permanency than those who are due to return. The evocation of spirits, especially in the form of necromancy (q.v.) is an important branch of the demonology of many peoples.

(d.) The vampire is a particular form of demon which calls for some notice. In Europe the Slavonic area is the principal seat of vampire beliefs, and as a natural development, means of preventing the dead from injuring the living have been evolved. The corpse of the vampire, which may often be recognized by its unnaturally ruddy and fresh appearance, should be staked down in the grave or its head should be cut off; it is interesting to note that the cutting off of heads of the dead was a neolithic burial rite.

(e.) The vampire is frequently blended in popular idea with the Poltergeist (q.v.) or knocking spirit, and also with the wer wolf (see LYCANTHROPY).

(f .) Dream demons are very common; in fact the word "night mare" (A.S. maer, spirit, elf) preserves this form of belief, which is found right down to the lowest culture. Horses too are said to be subject to the persecutions of demons, which ride them at night. Another class of nocturnal demons, the incubi and suc cubi, are said to consort with human beings in their sleep.

(g.) Corresponding to the personal tutelary spirit (supra, b) we have the genii of buildings and places, and a snake was a fre quent form for this kind of demon. The South African belief that the snakes which are in the neighbourhood of the kraal are the incarnations of the ancestors of the residents, suggests that some similar idea lay at the bottom of the Roman belief. To this day in European folklore the house snake or toad, which lives in the cellar, is regarded as the "life index" or other self of the father of the house; the death of one involves the death of the other, according to popular belief. The assignment of genii to buildings and gates is connected with the custom of sacrificing a human being or an animal at the foundation of a building. Sometimes a similar guardian is provided for the frontier of a country or of a tribe.

(li.) The animistic creed postulates the existence of all kinds of local spirits, which are sometimes tied to their habitats, some times free to wander. Especially prominent in Europe—classical, mediaeval and modern—and in East Asia is the spirit of the lake, river, spring, or well, often conceived as human, but also in the form of a bull or horse. Less specialized in their functions are many of the figures of modern folklore, some of whom have perhaps replaced some ancient goddess.

(i.) Certain aspects of the belief in plant souls demand more detailed treatment. Outside the European area vegetation spirits of all kinds seem to be conceived, as a rule, as anthropomorphic ; in classical Europe, and parts of the Slavonic area at the present day, the tree spirit was believed to have the form of a goat, or to have goats' feet.

Of special importance in Europe is the conception of the so called "corn spirit," by which the life of the corn is supposed to exist apart from the corn itself and to take the form, sometimes of an animal, sometimes of a man or woman, sometimes of a child. The animal identified with the corn demon is sometimes killed in the spring in order to mingle its blood or bones with the seed; at harvest-time it is supposed to sit in the last corn and the animals driven out from it are sometimes killed ; in other cases the reaper who cuts the last ear is said to have killed the "wolf" or the "dog," and sometimes receives the name of "wolf" or "dog" and retains it till the next harvest. The corn spirit is also said to be hiding in the barn till the corn is threshed, or it may reappear at midwinter, when the farmer begins to think of his new year of labour and harvest. Side by side with the conception of the corn spirit as an animal is the anthropomorphic view of it; and at the same time the association of gods and goddesses of corn with animal embodiments of the corn spirit is found.

(j.) In many parts of the world is found the conception termed the "otiose creator"; that is to say, the belief in a great deity, who is the author of all that exists but is too remote from the world and too high above terrestrial things to concern him self with the details of the universe. The operations of nature are conducted by a multitude of more or less obedient subordi nate deities, who shade off into demons of the usual type from whom they are hardly distinguishable.

Sometimes the gods of an older religion degenerate into the demons of the belief which supersedes it. (See WITCHCRAFT.) Expulsion of Demons.—Mention must be made of the cus tom of expelling ghosts, spirits or evils generally. Primitive peo ples from the Australians upwards celebrate, usually at fixed in tervals, a driving out of hurtful influences. Sometimes it is merely the ghosts of those who have died in the year which are thus driven out ; from this custom must be distinguished that of dismissing the souls of the dead at the close of the year and sending them on their journey to the other world; this latter cus tom seems to have an entirely different origin and is an essential part of the funerary ritual. In other cases it is believed that evil spirits generally or even non-personal evils such as sins are be lieved to be expelled. In these customs originated perhaps the scapegoat, some forms of sacrifice (q.v.) and other cathartic ceremonies.