Denmark

DENMARK (Danmark), a small kingdom of Europe, occu pying part of the peninsula of Jutland (Jylland) and a group of islands dividing the Baltic and North seas, lying between 54° 33' and 5 7 ° 45' N. and between 8° 5' and 12° 47' E., exclusive of the island of Bornholm. The southern part of the peninsula (Schleswig-Holstein) belongs to Germany. The northern extrem ity of the Danish part is actually insular, being separated from the mainland by the narrow and shallow Limfjord, which con nects the North sea with the Cattegat. Though broadest in the west, its connection with the North sea dates from 1825 only. The Skagerrack bounds Jutland on the north and north-west. Between the Cattegat and the Baltic, and between the base of the peninsula and south-western Sweden, lie the Danish islands. Of the total area of the kingdom (16,568 sq.m.), Jutland covers 11,408 and the islands in the Baltic 5,161 sq. miles. These con sist of the two large islands, Fffiren and Zealand, with smaller islands, chiefly, on their south sides, and Bornholm far to the east in the Baltic.

The solid geology is almost everywhere obscured by deposits of boulder clay lying generally on Cretaceous rocks, which out crop for example in Moen and Aalborg, giving rise to important lime and cement industries. Much of the Danish chalk, including the well-known limestone of Faxe, belongs to the highest or "Danian" sub-division of the Cretaceous period. In the south west a succession of strata, including lignite formations, inter venes between the chalk and the boulder clay. It is on the island of Bornholm only that older formations come to light. This island compares rather with south Sweden, and forms, in fact, the southernmost portion of the Scandinavian system ; boulder clay is absent in the south-west of the island, where Cambrian, Silurian, Jurassic and Cretaceous formations appear. Some parts of Denmark are supposed to have been raised out of the sea towards the end of the Cretaceous period, and may have been above water in various subsequent periods, but the final emergence was during the formation of the Ancylus lake towards the close of the Ice age. Recent research has greatly enlarged our knowl edge of the Pleistocene glaciation in its relation to early man; and its phases in the Baltic area have been correlated with the stages observed in the Alps. Successive layers of trees preserved among peat in certain small depressions found in many of the forests of Denmark show that the flora has undergone remark able variations to be connected with changes of climate during and since the glacial epoch. The first pine forests replaced a tundra flora during the period of the Ancylus lake, a fresh water inland sea caused by a phase of elevation in the area now occupied by the Baltic. Before the disappearance of the lake there fol lowed a still milder climate with oak forests ; while a later cooler and moister phase is represented by the beech forests which are so widely distributed in modern Denmark, and which apparently spread in the late Bronze and early Iron age. It is to the Gothi glacial and to the preceding Daniglacial retreats (equated by many respectively with the Achen and Laufer oscillations in the Alps), that the country owes its covering of morainic deposits.

The surface of the country is uniformly low, the highest ground. culminating in Ejer Bavnehoj in south-eastern Jutland, which is but 172 metres above the sea. There are, however, numerous hills between ioo and 150 metres in height. Undulating morainic formations of fertile clay, the legacy of the Pleistocene glaciation, are commonest in Zealand, Fiinen and east Jutland, where they form the basis of Denmark's most characteristic landscapes of rich corn-fields, meadows and beech woods. Ex tensive plains are in the west, consisting of poor sandy soils washed from the western edge of an ice-sheet which lay from north to south down the peninsula. These wide expanses of heather covered sands are broken here and there by morainic formations of an earlier glacial phase. They have been reclaimed for forest or arable land in the last 5o years, to the extent of nearly 5,000 sq.kms. The dune-islands and dunes form an almost continuous line along the west coast of Jutland from Blaavandshuk to the Skaw, and the dunes did great damage up to the end of last cen tury by drifting in over the cultivated areas and even destroying settlements, but they are now largely planted and secured by means of groynes.

Jutland.

Bordered by this sparsely-peopled zone, with a coast dangerous to shipping, the peninsula may be said to turn its back on the North sea : and its life has tended to orient itself towards the islands, where Copenhagen provides a metropolitan centre which contains, with Frederiksberg and Gentofte, 21% of the total population of the country. Esbjerg, the home of a large fleet of fishing vessels, and the origin of daily steamship services to England and France, is the only harbour on the west coast. The need for ports has become urgent of recent years, and new harbours are under construction (1928) at Hirtshals and Hanst holm. The drainage of the peninsula is typical of a low glaciated region. The Varde, Omme, Skjerne, Stor and Karur, sluggish and tortuous streams, flow through marshy tracts into the lagoons of the west coast, while the eastern Limfjord is flanked by the swamps known as Vildmose. The country's largest river, the Gudenaa, 8o m. in length, rises near the east coast and drains the Silkebore series of lakes, following a winding course into Randers Fjord (Cattegat). Off Slesvig (S. Jylland) is the island of Alsen in the Little Belt. Funen (Fyen), the main western island, is separated from the peninsula by the Little Belt, varying in width from io na. to the - m. strait which lies between the resort of Middlefart and the port of Fredericia, in Jutland. In form roughly oval, with a length from north-west to south-east of 53 m., and an area of 2,986 sq.km., Funen is closely allied to the mainland; and its fertile meadows among patches of woodland and boulder strewn hills are typically Danish. An archipelago, which includes Taasinge, Avernako and Dreio, lies to the south, enclosed by the narrow islands of Aero (16 m. in length) and Langeland (32 m.). On Langeland is the 13th century castle of Tranekjaer.

Zealand

(Sjaelland), the largest island in the kingdom, lies east of Funen, from which it is separated by the Great Belt, I I m. wide in its narrowest part. It is 82 m. N. to S. and 68 m. from E. to W., but the outline is very irregular. The area is 2,636 sq. miles. On the north lies the Cattegat ; on the east the Sound, narrowing to 3 m. off Elsinore; and on the south the straits beyond which come the island of Moen, Falster and Laaland. The undulating surface is little above sea-level, save that the Cretaceous hills of the south-east, especially in Moen, reach heights of over ioo metres. Of numerous coastal indentations the most important is the Ise Fjord on the north, with its east and west branches the Roskilde and the Lamme Fjords, penetrating some 25 m. inland. Small lakes among the glacial debris are common here as elsewhere in Denmark, those of Arre and Esrom in the north-east attaining notable dimensions.

Climate.

The climate is milder than that of most countries in the same latitude, for it is profoundly modified by maritime influences. No part of the land is more than 4o m. from the open sea, while numerous indentations carry equable conditions, and their effect is noticeable on the monthly weather maps. The mean annual temperature is 45.2° ; the average for July is about 61°, and for January about 32°. Frost occurs on an average on 20 days in each of the months from December to March. The eastern coasts are ice-fringed for some time, and both the Sound and the Great Belt are very occasionally impassable on account of ice. Variable winds (mainly west and south-west) of cyclonic origin lead to considerable variations from day to day, especially in the winter months. The average annual rainfall is about 24 in. show ing a tendency towards a maximum from July to November. The wettest month is September (2.95 in.), and April (1•14 in.) the driest. Thunderstorms are frequent in summer. At that sea son rainfall is greatest in central Jutland, where the higher ground produces an increase throughout the year; more rain falls in the east of the kingdom than in the west. The reverse is true of the distribution of winter rain. The most equable climate occurs on the North sea coast, wider temperature ranges marking the higher ground of central Jutland and the interior of Zealand. On the west coast a salt mist, hindering vegetative growth, exerts its in fluence inland for some 15-30 miles. For the most part, climate combines with location and soil conditions in rendering Den mark an essentially agricultural and pastoral land.The flora presents greater variety than might be anticipated. The ordinary forms of northern Europe grow freely in the islands and on the eastern coast ; while the heaths and sandhills of the Atlantic side have a number of distinctive species. The native Danish forest is almost exclusively made up of beech, but it comprises only one-third of the whole timbered area, extensive coniferous plantations having been made in recent years. These are, however, confined for the most part to Jutland, so that the beech remains characteristic of the landscape in the islands. The oak and ash are now rare; in the first half of the 57th century the oak was still the characteristic Danish tree. Large oak-woods have recently been planted. As we have seen, abun dant traces of ancient extensive forests of fir and pine are found. Numerous peat bogs with remains of trees supply a large propor tion of the fuel locally used. In Bornholm, the flora is more like that of Sweden ; not the beech, but the pine, birch and ash are the most abundant trees.

The wild animals and birds of Denmark are those of the rest of Central Europe. The larger quadrupeds are all extinct ; even the red deer, formerly so abundant that in a single hunt in Jut land in 1593 no fewer than 1,600 head of deer were killed, is now only to be met with in preserves. The sea fisheries are important. Oysters are found, but have disappeared from many localities, where their abundance in ancient times is proved by their shell moulds on the coast. The Gudenaa is the only salmon river.

Early Man.

A fine series of prehistoric remains of various dates are preserved either in the present-day landscape or in the famous museum at Copenhagen. This it owes in no small measure to its position on the fringe of the continental mass of Eurasia, a natural peninsula termination, just as Brittany is farther west, of long lines of movement from central Europe along the loess belt and up the German rivers. If this peripheral location some times meant poverty it must be remembered that Denmark also lies open to maritime influences from western Europe; and the meeting of these two contrasted culture streams resulted in the notable enrichment of Denmark's long tradition of settled life. The first certain evidence of human occupation is found in the Norre-Lyngby culture of the early Ancylus period, the distribu tion area of which comprises Denmark, Scania, Rugen and Northern Prussia. Its coarsely flaked flints and reindeer-horn axes give way, towards the end of the Ancylus period, to the civiliza tion called after the famous Danish site at Maglemose, near Mullerup, representing, in part, a northward extension of the Tardenoisian culture, but characterized by its greater use of bone implements.But the best-known palaeolithic or epipalaeolithic survival in Denmark falls in the Littorina period, when the climatic optimum of the 4th millennium B.C., marked by the spread of the oak tree, is the time of the "kitchen-middens" or shell-mounds. The people of the Baltic lived chiefly on the sea-shore, then some 25 f t. above its present level, f eeding f or the most part on fish and molluscs, the shells of which accumulated in huge mounds. This mesolithic industry represents a deterioration from a virile hunting life to a mere collecting of food, but it is marked by the introduction of the domesticated dog and, towards the close of the second (Entebolle) phase, by the use of coarse pottery, our first evidence of the potter's art in northern Europe. With these ex ceptions, Denmark, isolated by forest and as yet uninfluenced by western sea-borne cultures, remained in a primitive unprogressive condition until the 3rd millennium B.C.

Considerable diversity of opinion exists as to the position of Denmark in the transition period from stone technique to metal workings. The megalithic monuments seem to indicate maritime influence from the south-west and to suggest that Denmark shared in early coastal trade. Other important influences were also at work. In the single graves are found cord–ornamented beakers and perforated stone battle-axes. Some regard these as evidences of the rise of a strong native culture which later spread towards the south-east, but more emphasize the resemblances be tween them and similar finds in central Europe. They suggest that nomad warriors may have penetrated north-westwards along the loess, bringing with them a memory at least of metal using and possibly, in due course, some metal tools and weapons. Thus Denmark and other parts of western Europe would appear to have been on the periphery of metal-using civilizations and to have been stimulated by interactions between coastal traders, nomad warriors and the native peoples.

In the full Bronze age Denmark shared with the rest of Scandinavia a highly developed civilization. Thanks to the pre serving properties of the peat bog, we have detailed information on questions for the most part unsolved elsewhere; and the famous tumuli of Treenhoi, Ribe and of Borum-Eshoi, Aarhus, have yielded woollen articles of dress from both male and female burials. The bronze sword-hafts and shields with spiral decora tions are perhaps the most delicate examples of prehistoric craftsmanship f ound anywhere. Objects of Italian and Swiss origin are frequent, and demonstrate the wide commercial rela tions maintained by Scandinavia. The bronze-using civilization persisted long after iron had come into use in central Europe, but after 800 B.C. there came a decline consequent upon climatic deterioration and the formation of peat bogs. There is evidence for a southward movement of Scandinavian peoples of Wadic type through Jutland, for the proportion of long heads to broad in the graves of the Iron age (after soo B.c.) rises remarkably. Denmark remained unaffected by the Romans; and the conse quent revival, or rather survival, of pre-Roman elements in its outburst of energy in the dark ages is probably connected with this fact.

Population and Occupations.

While the farming popula tion is thickest on the most fertile soils, i.e., in the islands and in eastern Jutland, its density shows a close correlation within those regions with the forest areas and with the size of the estates and farms. Forest-free districts exploited by small holdings support ' the densest populations. There are indications that concentrated settlement was the rule until about i800, but since then the villages have been greatly reduced or become industrialized, and the isolated farm is to-day a very characteristic Danish feature. The total population in 193o was 3,55o,656, with an average of 214 per sq. mile. The density in the islands is 255, as compared with 142 for the peninsula. Against greater Copenhagen's 771,168 inhabitants, the next largest town, Aarhus, has 81,219 inhabitants (193o). The only other town with over 5o,000 is Odense. The provincial towns range up to 20,000. While the urban population (193o) amounted to almost half the total, in 1875 it constituted only one quarter; but the great conurbation of the capital ac counts for much of this increase. Since the World War the rural and urban populations have grown at approximately the same rates; the respective figures for 193o being 2,o39,594 and 1,511,062.Compared with agriculture, the natural resources of the coun try are of subordinate importance. Though coal is f ound in Bornholm, neither coal nor metals can be profitably mined any where. Extensive strata of bog-iron ore in Jutland are used for purifying purposes in gas works. The newer chalk is utilized in lime-burning while the limestone at Stevns is used as a build ing material. Chalk also forms the basis of an important cement industry. Tertiary and glacial clays are used in the tile industry, while calcareous deposits of clay have been widely utilized, par ticularly in Jutland, for soil-improvement. Bornholm supplies granite for building and paving, and kaolin for the china and paper manufactures, From the time of the kitchen-middens the fish of the shallow seas, belts and fiords have been exploited; and fishing contributed largely to Copenhagen's supremacy. Improved mar keting facilities and the use of motor boats have greatly increased its economic importance in recent years. The value of the yield increased from 8 million kroner in 1890 to about 36 million in 1926. Coast fishing supplies mostly cod, plaice, eels, herring and mackerel, while deep-sea fishing yields cod, plaice and haddock. In 1926, about 58% of the total catch was exported. Numerous co-operative marketing associations and an up-to-date railway sys tem facilitate rapid distribution.

Communications.

Regular connections with foreign coun tries are mainly by sea, either via Esbjerg, or with England, the Netherlands, Belgium and France. There is a German ferry pas sage for passengers and trains from Gedser to Warnemiinde and the Swedish services from Copenhagen to Malmo and from Elsinore to Helsingborg. The latter is also one of the main lines of communication with Norway. The main land route, the railway via Padborg, is Slesvig to Hamburg. Denmark possesses some 5,000 km. of railways, of which nearly one-half belong to the State, while the State and the larger towns hold nearly all the shares in the "private" lines. There are highly organized train ferry schemes f or communication among the islands and between these and Jutland. Motor transport, similarly facilitated by low land relief, is highly developed, and air traffic is progressing with Copenhagen as a centre of international lines.

Government and Constitution.

The constitution of Den mark is laid down in the Act of June 5, 1915, amended in 1920 on the restoration of North Slesvig in accordance with the treaty of Versailles. It marks, f or the most part, a return to the con stitution of 1849. Legislative authority rests jointly with the crown and parliament; the executive power is vested in the crown, while the administration of justice is exercised by the courts. Parliament consists of two chambers, the Landsting (senate) and the Folketing (lower house). The franchise is held by all persons over 25 years of age with a fixed place of abode. The members of the Folketing, at present 149, are elected for four years. Of the members of the Landsting, 56 (including one from the Faeroe Is.) are elected by the votes of the Folketing's electors who are over 35 years of age; while 19 members are elected by the former Landsting. The Rigsdag (parliament) must meet every year on the first Tuesday in October. The privy council is the highest executive power in the State; it deals with all new bills and all important Government measures. For administrative purposes there are 22 Amter (counties), each of which is under the super intendence of a governor. Local government is largely in the hands of the municipal councils.

Religion and Education.

The church of Denmark is Lutheran, which was introduced as early as 1536. The king must belong to it. There is complete religious toleration, but though most of the important Christian communities are represented their numbers are very small. There are nine dioceses; the pri mate is the bishop of Zealand, and resides at Copenhagen, but his cathedral is at Roskilde. According to the census of 1921 there were 3,221,843 Protestants, 22,137 Roman Catholics, 535 Greek Catholics, 5,947 Jews and 17,349 of other or no confession.

Since 1814 education has been compulsory for those aged

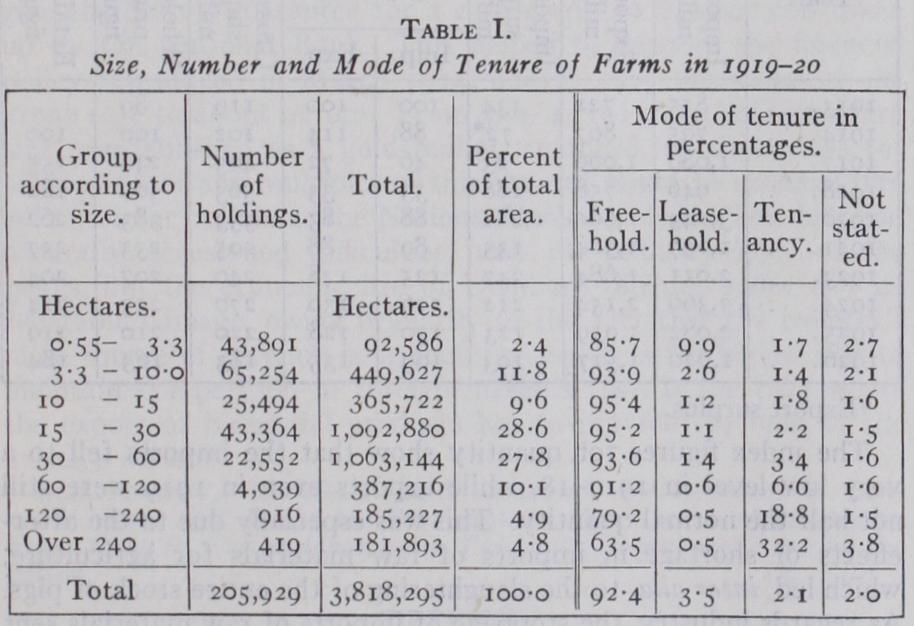

7 to 14 years. The last school laws (1903) have made this instruction gratuitous for the greater part. However, in 1926, but 34 of these schools were Government institutions; 3,852 were maintained locally, and 607 were private. Their teachers are trained in about 20 normal schools. After five years of elementary instruction, pupils may receive four years of secondary education and may then proceed to a high school, of which there are some 300. Here there is a choice between classical, modern language and scientific courses terminated by a State examination. There are so to 6o popular high schools for adults, all private, but all assisted by the State. For specialized study there are 23 agricultural schools (one including veterinary courses), over 25o technical schools, and institutions for dentistry, pharmacy and art. The Royal uni versity, in Copenhagen, was founded in 1479 and has 4,00o to 5,00o students. Women are received on a parity with men in all departments. (E. E. E.) Agriculture.—Under the Treaty of Versailles Denmark in creased her area by the addition of a part of the old Danish dis tricts in Slesvig comprising about 3,28osq.kilo. of farm land and 14,364 farms. The number of holdings has been increased, partly by private parcelling out and partly by the establishment of many small holdings with State aid, so that the total number of agri cultural holdings in 1920 was 205,929 as against 172,000 in 1901.As a result of the Land Laws of 1899 and 1919 about I i,000 new small holdings were created during the 17 years 1910-26. The average number of holdings established each year from 1920 to 1926 was about i,000. The total number of holdings in 1927 was about 214,000 of an average size of about 18 hectares each. With the increase in the number of holdings there was a change in the mode of tenure, from tenancy to freehold. The law of June 3o, 1919 abolished leasehold as far as large and middle-sized holdings were concerned. Leasehold is still allowed for small holdings, and in 1919 about 5, 70o small holdings were held on lease or rented, the Slesvig part excluded.

It will be seen that the middle-sized farms of from 1 o to 6o hectares form the majority, comprising 66% of the total area. The small holdings of under io hectares form 14% and the farms of above 6o hectares form about 2o%. In 1919 only 5.7% of all the farms were not worked by the owners as against 11.6% in the year 1901.

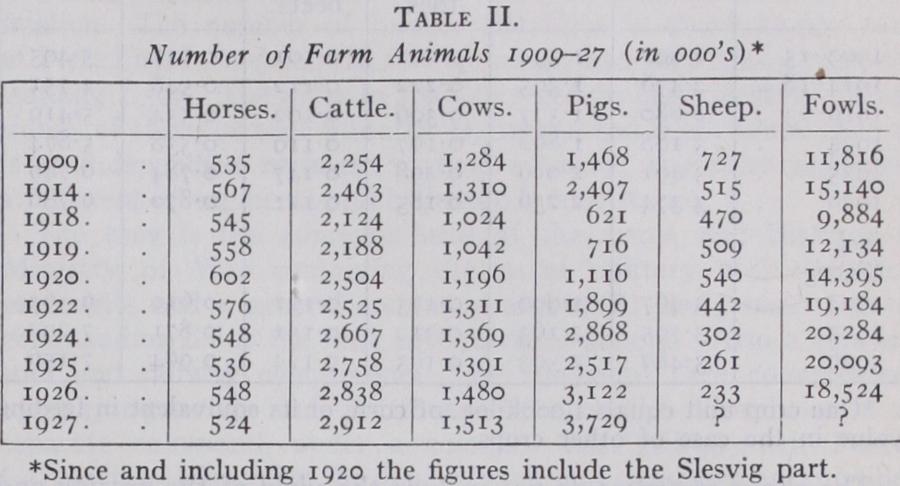

Production and Marketing.—The World War and its after effects naturally vastly influenced production and marketing. The great development in and industrializing of animal production characteristic of Danish agriculture during the last 3o years previ ous to the war have made Denmark more dependent on interna tional trade than the agricultural activities of most other countries. In 1913 Denmark exported agricultural produce to the amount of about S 50,00o,000kr., about 9 7 % of the exports being animal products, and imported corn and feeding stuffs to the value of 181,000,000 kroner. The war seriously affected this development, especially after the submarine warfare began in Feb. 1917. The effect of the blockade and the post-war recovery may be deduced from the following table :— The large decrease in the number of milch cows and pigs during the war does not show the full decrease in animal products. The annual yield per cow decreased from about 2,75okilog. milk in 1914 to about 1,81okilog. in 1919, and in terms of butter this means a decrease in production from 143 million kilog. in 1914 to 76 million kilog. in 1918. It was not until 1922 that the yield reached the 1914 level, but in 1926 it rose by an additional 25o kilog. per cow, the average yield of milk per cow per annum being estimated to be a little more than 3,00o kilogrammes.

*Since and including

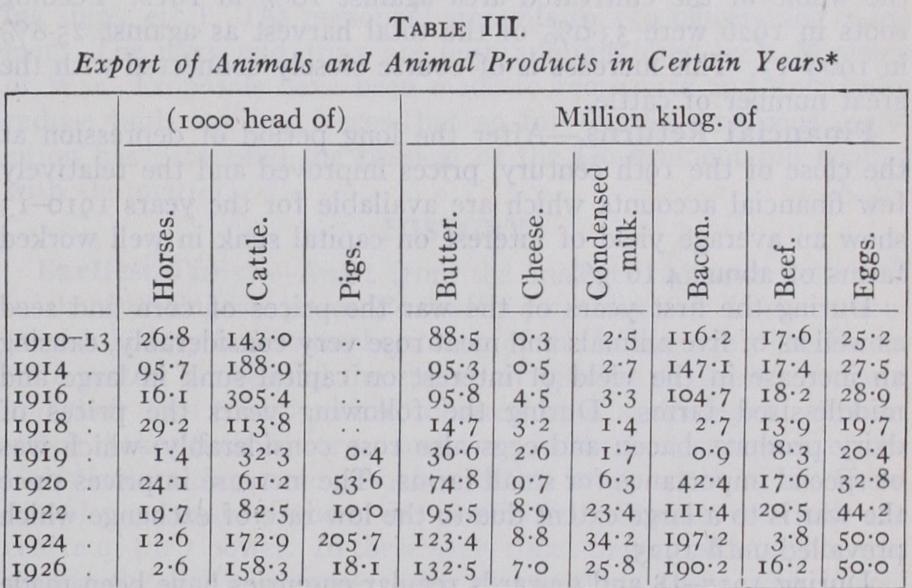

1920 the figures also include the Slesvig part.The heavy reduction after 1917 was mainly due to the absolute cessation of the import of feeding stuffs, but partly to the very poor harvests during the years 1917-18 especially with regard to grain crops. These reduced the bacon export in 1919 to the mini-, mum of i,000,000 kilogrammes. The export of animal products only reached pre-war level in 1923 and 1924. The increase is largest for the export of dairy produce, pigs, bacon and eggs, while the export of cattle and beef taken as a whole is about the same as before the war and there is a considerable decrease in the export of horses mainly due to difficulties experienced on the German market.

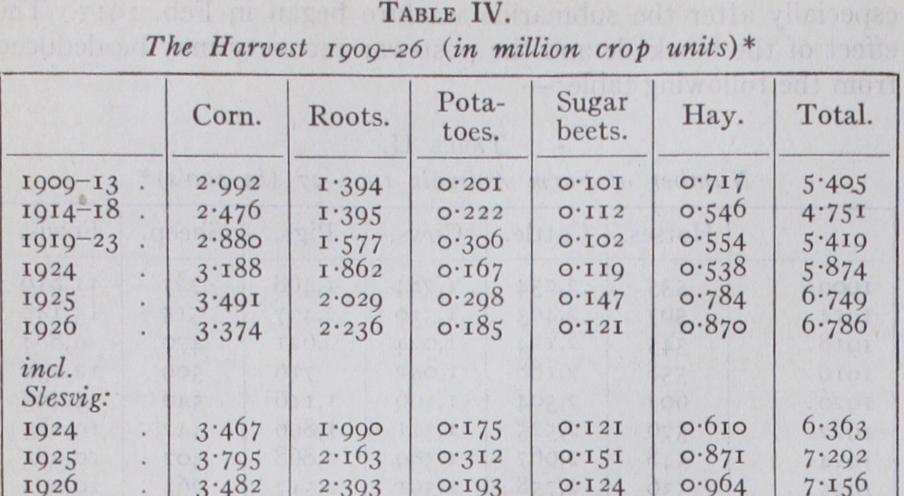

The large increase in the export, both during and after the war, of live pigs, cheese and condensed milk is very remarkable. There has been a corresponding decrease in the export of fresh milk and cream. The total value of the export of animal products was in 1926 I,o95,000,00o kroner against 462,000,00o kroner during the five-year period of 1909-13. The gold value of the export for 1926 is I,o69,000,00o kroner or about twice the value of the pre-war export. The large decrease in animal production from 1914-19 also decreased the plant production, as farm manure plays a prom inent part in Danish agriculture, and the decrease in manure is roughly proportionate to the decrease in the import of feeding stuffs. Moreover, the import of nitrogen and phosphates was partly stopped during the years 1917-18 on account of the world shortage caused by the war.

*One crop unit equals i,000kilog. of corn, or its equivalent in feeding value in the case of other crops.

The above statistics do not include the yield of the grazing and green fodder area nor the yield of various crops grown for the pur pose of commercial transactions. If these crops are also included the total production of 1926 will be about 9,300,00o crop units including Slesvig. The decrease during the World War is specially noticeable with regard to the corn and hay crop but it is partly due to a decrease in the arable area of these crops, while the area of roots, potatoes and sugar beets was greatly increased during the same period, and this increase in roots continued after the war so that the area under these crops in 1927 was about 13.8% of the whole of the cultivated area against io% in 1912. Feeding roots in 1926 were 33.o% of the total harvest as against 25.8% in 1909-13. This increase is of course closely connected with the great number of cattle.

Financial Returns.

After the long period of depression at the close of the i9th century, prices improved and the relatively few financial accounts which are available for the years 191 o-13 show an average yield of interest on capital sunk in well worked farms of about 4 to 5%.During the first years of the war the prices of corn and seed as well as of live animals and meat rose very considerably, causing an increase in the yield of interest on capital sunk in large and middle-sized farms. During the following years the prices of dairy produce, bacon and eggs also rose considerably, which was of special importance for small farms. The increase in prices since the war is to a large extent due to the low rate of exchange which prevailed until 1925.

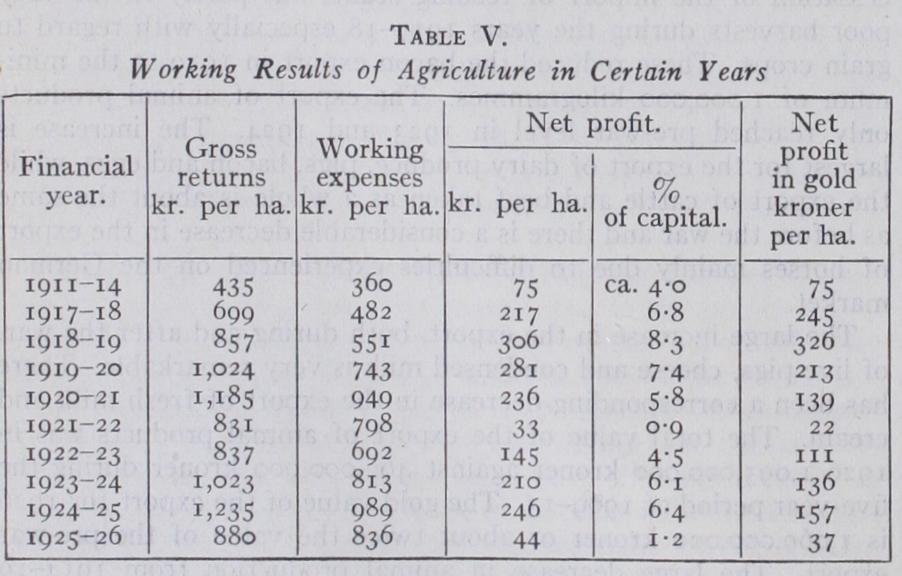

During 1917-18 and onwards regular enquiries have been made with regard to the economic position of large numbers of agricul tural holdings of an average area of about 45 hectares each. The results of these enquiries are shown in Table V.

The great increase in gross returns and in net profit was notice able as early as 1917-18, but while the increase in the gross returns was continued until 1920-21 the net profit was at its highest in decreasing until the critical year 1921-22, and rising again until 1924-25. During the spring of 1925 a new period of deflation began which developed quickly during the summer when the value of the krone rose in the course of three months from about 7o to 93% of its pre-war value, and during the year 1926 the krone reached par.

The heavy deflation and the following decrease in the world market prices of agricultural products have involved very difficult times for Danish agriculture as the decrease in a great number of the working expenses (wages, costs of repairs, etc.) has not been able to keep pace with the decrease in prices of agricultural prod ucts. During the first year, however, bacon kept tolerably good prices and, besides, the harvest in 1925 was beyond the average, so that the result of the year 1925-26 was not as bad as that of the year 1921-22. Later the prices of bacon dropped violently, and this in connection with the bad harvest in 1927 further deteriorated the economic position of Danish agriculture.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.

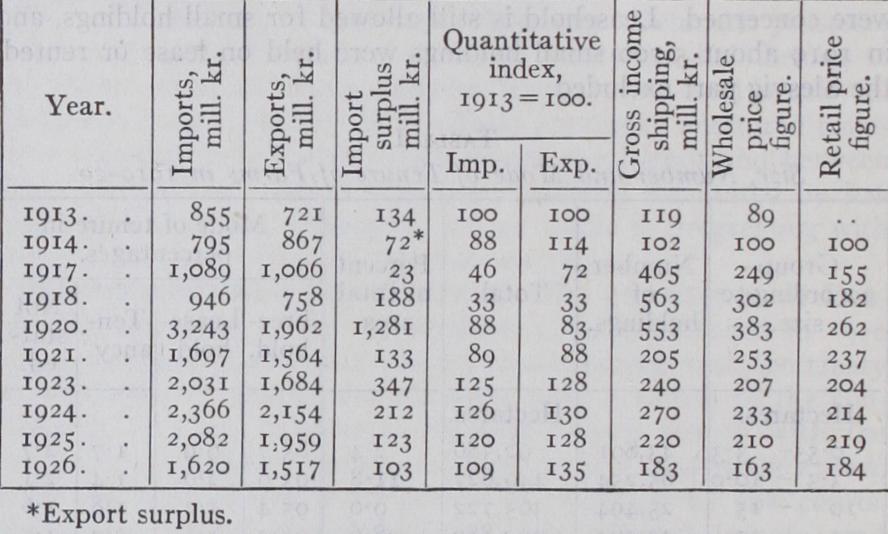

Stat. Tabelvaerk, Femte Raekke, Litra D. No. Bibliography. Stat. Tabelvaerk, Femte Raekke, Litra D. No. 28-47 ; (Statistical Tables, vol. v., Litra D. No. 28-47) ; Stat. Med delelser, Fjerde Raekke; Statistical Communications, vol. iv. (Copen hagen, 1910-27) ; Stat. Aarbog. (1910-27) ; Statistical Year Books (Copenhagen, 1910-27) ; Undersogelser over Landbrugets Dri f is f or hold, 2-I0 (1919-27) ; Research into Agricultural Management, 2-10 (Copenhagen, 1919-27) ; H. Faber, Agricultural Production in Den mark, extract from the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society (1924) ; Stat. Efterretninger, 1927 No. 28 and No. 32 (1927) ; General Statistical Intelligence, 1927, No. 28 and 39 (Copenhagen, 1927). (O. H. L.) Financial and Economic Development.—Denmark shared with the rest of the world in the general rise in values which cul minated towards the close of 1913. Unemployment, which was 9.4% in 1911, fell in 1912 to 7.5% and in 1913 to 7.3%, and the production and export of agricultural products, especially butter. bacon and eggs, a factor of great importance in the economical life of the country, was on the increase. The total exports of home produce, to which agriculture normally contributes nearly 9o%, amounted in 1911 to 537,000,000, in 1912 to 597,000,000, and in 1913 to 63 7,000,00o kroner. The course of foreign trade in 1913 26 was as follows:— The index figures for quantity show that the imports fell to a very low level in 1917-18, while exports even in 1919 were still not half the normal quantity. This was especially due to the after effects of shortage in imports of raw materials for agriculture, which led, inter alia, to the slaughtering of the entire stock of pigs. As regards industry, the stoppage of imports of raw materials sent up the unemployment percentage, which had been normal in 1915 and well below the normal in 1916, to io% above normal in 1917, while in 1918 it was io6% and in 1919 still 24% above the average for 1909-13.

The table further shows that imports were only slightly in excess of exports during the actual years of war, and this excess was more than balanced by the income derived from shipping. In 1919-2o, on the other hand, the excess was very high, partly be cause quantities of goods purchased during the war could now be brought home, and partly because of the anticipation of a great demand from Central Europe and the Baltic which, however, failed to materialize.

Rate of Exchange and Price Level.—These features in foreign trade were of great importance to the rate of exchange. The Danish krone rose above par in regard to the pound sterling and the dollar to such an extent that on Oct. 2, 1917, the pound had fallen to 13•0o kr. (18.16 kr. at par) . Subsequently exports de creased greatly, and there was an expansion of credit, stimulated to no slight degree by the considerable loans advanced by the Na tional Bank and the leading private banks to German, English and French banks during the war, and at the close of the war to the State too ; also on account of the large quantity of money which was necessitated by the reintegration of Slesvig. Moreover the re awakening of commerce and trade after the blockade caused large demand for credit. All this resulted in an increase in the volume of purchasing power and helped to raise the level of prices and to move the exchanges against Denmark. At the end of the war, therefore, the value of the Danish krone fell below parity, the rate of exchange to the pound sterling mounting on Nov. 17, 192o, to 25.S6. In connection herewith the wholesale and retail prices rose, so much the more because the war-time price regulation arrangements were gradually being withdrawn.

Financial Policy.—The universal fall in prices, however, also had a very marked effect in Denmark; in 1921, unemployment was four or five times the normal, and the import surplus declined, as the table shows, to only 133,000,00o kroner. Before the middle of 1921, the pound sterling was almost at par. But this rate could not be maintained, and the exchange therefore rose again to 20-22 kroner. Here it remained during 1921 and for part of 1922, but the effects of the fall in prices now appeared, and several banks were in difficulties. The Landmandsbank, the largest in the coun try, was reconstructed with the aid of the State and the National Bank. During 1923-24 the value of the pound sterling remained, with various fluctuations, about the level of 26 kroner. But there was still an active demand for a return to the old gold parity, and in March 1924, the National Bank commenced a systematic restriction of credit, which brought the gold value of the krone, measured in dollars, up to about 65 ore at the close of the year.

This financial policy was now supported by a law of Dec. 1924, authorizing the Minister of Finance to levy extraordinary taxes for the covering of a loan with the National Bank in connection with the reconstruction of the Landmandsbank, and further, to give the State's guarantee for a cash credit of $40,000,00o taken up by the National Bank. This helped to support the financial policy introduced in March 1924, and in 1925 the value of the krone rose to about 92 ore. From Jan. 1, 1927, the gold standard was re-established as a gold bullion standard, so that notes for 28,00o kroner and multiples of this amount might be changed into gold (coin or bullion as the National Bank decided). The deflation naturally occasioned difficulties both for industry and for the banks, but the economic life of Denmark did not suffer any ir reparable damage, owing primarily to the fact that the country's main source of revenue is agriculture, which is far better able to maintain competition in foreign markets than is the case where the export of industrial products has to provide the bulk of the nation's income.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-H.

Westergaard, Economic Development in DenBibliography.-H. Westergaard, Economic Development in Den- mark before and during the War (1922) ; also a series of articles by Einar Cohn in Nationalokonomisk Tidskrift (Copenhagen) during the period. (E. Co.) The Danish army looks back upon an honourable record of service, dating back to the Thirty Years War (1618-48). Den mark, having emerged in a poverty-stricken state from the Napo leonic Wars, was next involved in the first Schleswig-Holstein War of 1848. The most onerous service, in connection with those territories, that fell upon the Danish army occurred in 1864, in February of which year German and Austrian troops invaded the country in overwhelming force. Danish neutrality was main tained in the European Wars of 1870 and 1914-18; Denmark profiting by an extension of her frontiers as the result of the defeat of Germany.Under the Army Act of 1922, recruits are entered on conscrip tion rolls at 17 years, and receive military training for five months with four subsequent annual trainings for shorter periods, be tween the ages of 19 and 25. Cavalry and artillery do somewhat longer training. The "Landstorm" troops, for auxiliary services, do only two months. Service is for eight years in the first line and for eight years in the reserve, and during these 16 years the military authorities must be kept informed of the addresses of the men, who are not allowed to leave the country without per mission. The number of budget effectives is about 10,90o and of First Line men doing the full training 7,050, and the Landstorm training 1,500. The units in the army are grouped in three "divi sions" of three or four infantry regiments and other arms. There is an independent regiment of field artillery, also coast artillery, a regiment of engineers and train and labour troops.

The king is the supreme head of the army, and there is a Ministry of War containing the usual military and civil de partments and a general command and staff; the general officer commanding holds the rank of lieutenant-general. Also a general staff and railway commission. The "divisions" are commanded by major-generals and distributed territorially. Bornholm is a separate command, under a colonel. The Military Air Force (strength 95) is under the general staff and possesses an aviation school, where conscripts who volunteer are trained. Conditions are under revision (1928).

See also League of Nations, Armaments Yearbook (1928) ; Cam bridge Modern History (vol. xi.) .

Navy.

The fleet is composed of 5 coast defence ships and monitors, the largest of which is the "Niels Juel," completed in 1918, which displaces 4,200 tons and carries an armament of ten 5.9 inch guns and two 17.7 inch torpedo tubes; 2 very small cruisers, 23 torpedo boats, 14 submarines, and 24 miscel laneous units (mine ships, patrol boats, torpedo transport, train ing ships, etc.). The personnel amounts to 150 officers and 2,000 men. The navy and army are both administrated by a Ministry of War. Proposals have been made to reorganize and drastically reduce both fighting forces, but so far (1928) strenuous oppo sition has prevented the passage of the Government bill dealing with the matter. (X.) Earliest Times.—Apart from the ancient traditions preserved in the Old English poem Beowulf (q.v.), little is known about Danish history before the beginning of the Viking age. The Danes were seated far beyond the sphere of interest of Roman writers, and their own traditions are coloured by a mythological element which makes their history uncertain. In the first centuries of the Christian era they were probably settled in the south of the Scan dinavian peninsula, where the province of Skaane was long the centre of their power. In these early times they must have counted among the Baltic peoples rather than among those who looked towards the North sea. It is further probable that their occupa tion of Jutland and the adjacent islands belongs to the 5th and 6th centuries, and was made possible by the migration of the Anglian peoples to Britain in that age. Even after their establish ment in these regions, it was long before they came into perma nent contact with the peoples of western Europe. The Frisians (q.v.) were the greatest naval power in the North sea in the 6th and 7th centuries, and the destruction of this power by the Franks probably gave to the Danes the opportunity of raids on a great scale towards the west. In the 8th century the Danes were ruled by kings claiming mythological ancestry of the kind asserted by most royal families of the age. They were in occupation of Skaane, Zealand, and the lesser islands in its neighbourhood, and the north of the Jutish peninsula. They possessed at Leire, in Zealand, a very ancient religious sanctuary, near which stood the chief residence of their kings. They were as yet hardly touched by the wave of missionary enterprise which had brought the neighbouring Frisians within the influence of the Western Church. The conversion of Denmark belongs to the loth century.The northward extension of Charlemagne's dominion brought him and his successors into temporary relations with individual Danish kings. In the frequent quarrels between different members of the Danish royal family it was natural for one or other of the opponents to seek the support of the emperor. But the historic facts brought to light by such negotiations are meagre. It is, in particular, doubtful whether the individuals who to Frankish writers were kings of the Danes were in reality more than local rulers, of royal descent, but limited authority. In any case, the interest of Danish history in this age lies outside Denmark itself, in the expeditions led by Danish chiefs and in the new political communities which they founded in the west of Europe. (See