Dentistry

DENTISTRY, a special department of medicine, dealing with diseases of the teeth and their treatment. (For anatomy see TEETH.) Until well into the Igth century apprenticeship afforded the only means of acquiring a knowledge of dentistry, but in Nov. 184o was established the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery, the first college in the world for the systematic education of dentists. This, combined with the refusal of the medical schools to furnish the desired facilities for dental instruction, placed dentistry for the time being upon a footing entirely separate from general medicine. The British medical schools later revised their policy and special courses of instruction are arranged to meet the demands of the various examining bodies. Recently an official dental register corresponding to the medical register has been instituted in Great Britain.

The most important dental research of modern times is that carried out by W. D. Miller of Berlin (1884) upon the cause of caries of the teeth, a disease said to affect the human race more extensively than any other. Miller demonstrated that, as pre vious observers had suspected, caries is of bacterial origin, and that acids play an important role in the process. This work has been given greater precision by McIntosh, James and P. Lazarus Barlow who isolated a group of bacilli (B. acidopliilus odontolyti cus) from carious teeth which was capable of producing the characteristic changes under experimental conditions. Dental caries and septic conditions of the gums bear highly important relations to more remote or systemic diseases, furnishing avenues of entrance for pathogenic bacteria, notably those of actinomyco sis and pyaemia.

Operative Dentistry.

The art of dentistry is usually divid ed arbitrarily into operative dentistry, the purpose of which is to preserve as far as possible the teeth and associated tissues, and prosthetic dentistry, the purpose of which is to supply the loss of teeth by artificial substitutes. The filling of carious cavities was probably first performed with lead, and was sufficiently prevalent in France during the 17th century to bring into use the word plombage, which is still occasionally applied in that country to the operation of filling. Gold as a filling material came into gen eral use about the beginning of the I gth century.' Tin foil was also used to a limited extent.The dental engine in its several forms is the outgrowth of the simple drill worked by the hand of the operator. It is used in 'The filling of teeth with gold foil is recorded in the oldest known book on dentistry, Artzney Buchlein, published anonymously in 153o, in which the operation is quoted from Mesue (A.D. 857), physician to the caliph Haroun al-Raschid.

removing decayed structure, and for shaping the cavity for in serting the filling. The rubber dam invented by S. C. Barnum of New York (1864) provided a means for protecting the field of operations from the oral fluids, and extended the scope of operations even to the entire restoration of tooth-crowns with cohesive gold foil. Its value has been found to be even greater than was at first anticipated. In all operations involving the ex posed dental pulp or the pulp-chamber and root-canals, it is the only efficient method of mechanically protecting the field of oper ation from invasion by disease-producing bacteria.

The difficulty and annoyance attending the insertion of gold, its high thermal conductivity, and its objectionable colour have led to an increasing use of amalgam, gutta-percha, and cements of zinc oxide mixed with zinc chloride or phosphoric acid. Attention has also been devoted to restorations with porcelain and porcelain like cements.

Until recent times the exposure of the dental pulp inevitably led to its death and disintegration, and, by invasion of bacteria via the pulp canal, eventually caused the loss of the entire tooth. A rational system of therapeutics, in conjunction with proper antiseptic measures, has made possible in many cases a conserva tive treatment of the dental pulp when exposed, and successful treatment of pulp-canals when the pulp has been devitalized either by design or disease. The conservation of the exposed pulp is effected by the operation of capping. In capping a pulp, irritation is allayed by antiseptic and sedative treatment, and a metallic cap, lined with a non-irritant sedative paste, is applied under aseptic conditions immediately over the point of pulp exposure. A filling of cement is superimposed, and this, after it has hardened, is covered with a metallic or other suitable filling. The utility of arsenious acid f or devitalizing the dental pulp was discovered by J. R. Spooner of Montreal, and first published in 1836. The painful action of arsenic upon the pulp was avoided by the addition of various sedative drugs—morphia, atropia, iodoform, etc.—and its use soon became universal. Of late years immediate surgical extirpation under novocaine is in use, and by novocaine also the pain incident to excavating and shaping of cavities in tooth structure may be controlled. To fill the pulp chamber and canals of teeth after loss of the pulp, all organic remains of pulp tissue should be removed, and then, in order to prevent the entrance of bacteria, and consequent infection, the canals should be perfectly filled. Upon the exclusion of infection depends the future integrity and comfort of the tooth. Numer ous methods have been invented for the operation. Pulpless teeth are thus preserved through long periods of usefulness, and even those remains of teeth in which the crowns have been lost are rendered comfortable and useful as supports for artificial crowns, and as abutments f or assemblages of crowns, known as bridge-work.

Malposed teeth are not only unsightly but prone to disease, and may be the cause of disease in other teeth, or of the associated tissues. By the use of springs, screws, vulcanized caoutchouc bands, elastic ligatures, etc., as the case may require, practically all forms of dental irregularity may be corrected, even such pro ' trusions and retrusions of the front teeth as cause great disfigure ment of the facial contour.

The extraction of teeth, an operation which until quite recent times was one of the crudest procedures in minor surgery, has been reduced to exactitude by improved instruments, designed with reference to the anatomical relations of the teeth and their alveoli, and therefore adapted to the several classes of teeth. The operation has been rendered painless by the use of anaes thetics.

Dental Prosthesis.

The fastening of natural teeth or carved substitutes to adjoining sound teeth by means of thread or wire preceded their attachment to base-plates of carved wood, bone or ivory, which latter method was practised until the introduction of swaged metallic plates in the latter part of the i8th century. An impression of the gums was taken in wax, from which a cast was made in plaster of Paris. With this as a model, a metallic die of brass or zinc was prepared, upon which the plate of gold or silver was formed, and then swaged into contact with the die by means of a female die or counter-die ot lead. The process is essentially the same to-day, with the addition of numerous im provements in detail, particularly that of using vulcanite in place of metal. The discovery, by Gardette of Philadelphia in 1800, of the utility of atmospheric pressure in keeping artificial dentures in place led to the abandonment of spiral springs. A later device for enhancing the stability is the vacuum chamber, a central de pression in the upper surface of the plate, which, when exhausted of air by the wearer, materially increases the adhesion. The base plate is used also for supporting one or more artificial teeth, be ing kept in place by metallic clasps fitting to, and partially sur rounding, adjacent sound natural teeth, the plate merely covering the edentulous portion of the alveolar ridge. It may also be kept in place by atmospheric adhesion, in which case the palatal vault is included, and the vacuum chamber is utilized in the palatal portion to increase the adhesion.Metallic bases were used exclusively as supports for artificial dentures until in 1855-56 Charles Goodyear, Jr., patented in England a process for constructing a denture upon vulcanized caoutchouc as a base. Several modifications followed, each the subject of patented improvements. Though the cheapness and simplicity of the vulcanite base has led to its abuse in incompe tent hands, it has on the whole been productive of much benefit. It has been used with great success as a means of attaching por celain teeth to metallic bases of gold, silver and aluminium. It is extensively used also in correcting irregular positions of the teeth, and for making interdental splints in the treatment of fractures of the jaws. For the mechanical correction of palatal defects causing imperfection of deglutition and speech, which comes distinctly within the province of the prosthetic dentist, the vulcanite base produces the best-known apparatus. Two classes of palatal mechanism are recognized—the obturator, a palatal plate, the function of which is to close perforations or clefts in the hard palate, and the artificial velum, a movable at tachment to the obturator or palatal plate, which closes the open ing in the divided natural velum and, moving with it, enables the wearer to close off the nasopharynx from the oral cavity in the production of the guttural sounds. Vulcanite is also used for ex tensive restorations of the jaws after surgical operations or loss by disease, and in the majority of instances wholly corrects the def ormity.

The progress of dentistry since 'goo has been more rapid and more radical than in any previous period. The cause of this progress was the general advancement in knowledge due to the accumulation of data from scientific investigation and the appli cation of the knowledge thus acquired to the prevention and treatment of disease.

Septic Foci.

In several communications on septic dentistry, notably in an address delivered in 'gm at McGill university, Montreal, Dr. William Hunter, of London, criticized badly con ceived and unskilfully executed dental restorative operations, especially in crown and bridge work, and the treatment of pulp less teeth, which was performed without regard to surgical asepsis. He showed that operations so performed leave septic foci that cause septicaemic conditions, as well as infections in remote parts of the body.Hunter's criticisms immediately bore fruit. Bacteriological and X-ray examination of teeth and jaws, particularly in so called pyorrhoea alveolaris, quickly became the rule.

Change of Interest and Development.

The total effect of this evidence, both clinical and scientific, upon the develop ment of dentistry has been little short of revolutionary. Hitherto, the major feature of dental interest, upon which the attention of the profession was concentrated, had been the development and perfection of manipulative procedure in restorative operations. The ingenuity expended and the excellence of the results at tained became the outstanding characteristics of dental practice; and the restoration by prosthetic or operative means of the mas ticatory mechanism damaged by partial or total loss of teeth was its dominating ideal. There is now an enforced recognition in the professional, as well as in the lay mind, of the importance of the welfare of the tissues and organs of the mouth. In the dental profession the consequent changes of technical procedure and objectives have been fundamental. The ideal of mechanical per fection in the methods and appliances by which the dental sur geon restores the patient's power to masticate, is now regarded as a remedial measure subservient to the larger ideal of normal mouth health.

Oral Hygiene in Schools.

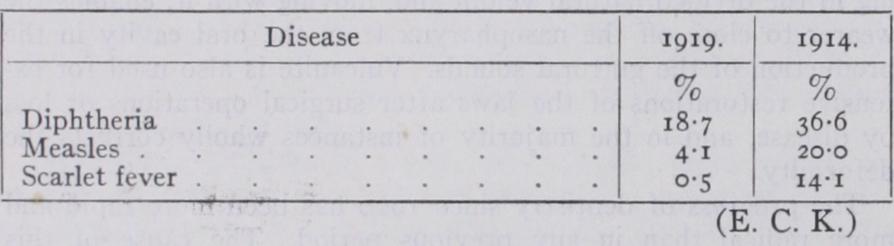

One of the principal factors which extended and popularized this knowledge is the oral hygiene move ment, an effort to demonstrate practically that school children, relieved of the disabilities arising from infected mouths and dis eased teeth which handicap normal development, show improved physical and mental efficiency. The Cambridge experiment, in augurated in 1907 by the late George Cunningham, of Cambridge, England, was perhaps the earliest practical test. The analogous work of Dr. Ernst Jessen, of Strasbourg, introduced oral hygiene into the public schools of a number of towns in Germany. In the United States the utility of the movement was tested in the Ma rion school of Cleveland, O., in 1910, and in 1919 there was com pleted, under conditions yielding accurate figures, a five years' test of applied mouth hygiene in the public schools of Bridgeport, under the direction of Dr. A. C. Fones.In this test 20,000 children of the first five school grades were under observation and treatment. The average number of car ious cavities was found to be over 7% per child; 30% claimed that they brushed their teeth occasionally; 6o% stated that they did not use a tooth-brush and io% had fistulous openings on the gums from abscesses at the roots of decayed teeth. Systematic application of oral hygiene, the intelligent and systematic use of the tooth-brush and the elimination of accretions, dental decay and suppurative conditions were followed by great improvement in general health and mental efficiency. Whatever may be the full explanation it is certain that deaths of Bridgeport children from diphtheria, measles and scarlet fever were fewer after oral hygiene had prevailed (i g i g) than they were before (I 9 I 4) . This is seen from the following table:— Under the direction of Supt. Willis A. Sutton, a dental clinic was installed in a school of 987 pupils in Atlanta and a hygienist, a dentist, a dietitian and a visiting teacher were selected. The number of days the children had been absent, in the past year, causes of the absences, the number of subject failures and the physical condition of each child as to weight and general appear ance were all carefully noted. Each child's mouth was then put in good condition and after three weeks new records were kept. All other factors entering into improvement were as carefully eliminated as possible. Upon comparison of the two records many significant deductions were made. First, the 987 children had less absences than the preceding year. Second, whereas the preceding year practically 20% had failed in one or more subjects, the year following the experiment less than 6% had failed. Third, every child in the entire group had gained in weight, ranging from 6 lbs. for the 9 months' period to 22 lbs., with an average of I I•2 pounds. Normally an average gain of about 8 lb. would have been expected. Fourth, the general appearance of the children had im proved remarkably, and they were far more spontaneous and happy than before. The dental clinics were then installed in other schools, with the result that of the 6o.000 children enrolled, 6,000 more per day attended school than formerly. The percentages of failures were reduced in the elementary schools by 8% and in the junior and senior high schools by 6%. The direct saving in money was $1 5o,000–$200,00o per year in a budget of $3,000,000.

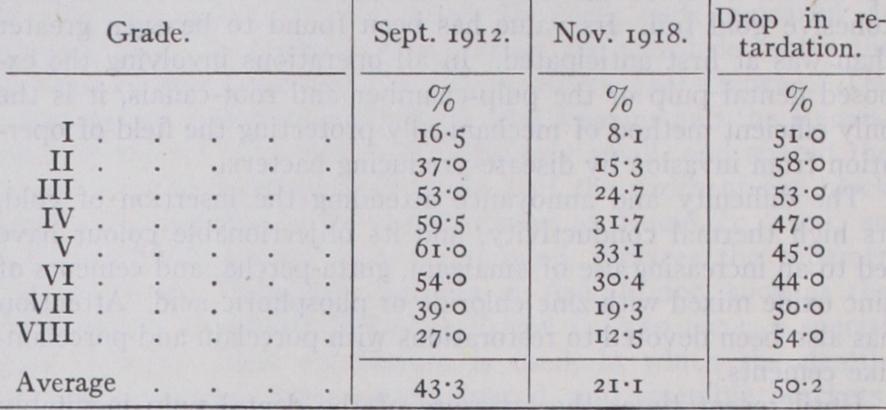

(W. A. S.) Dental Disease and Mental Efficiency.—An improvement in mental efficiency is deduced from the reduction in the percent age of retarded children, i.e., children who are not less than two years older than the normal age for the school grade to which they should belong. The percentage of retarded children before and after the introduction of mouth hygiene in the Bridgeport schools is shown in the following table:— Retardation represents inability of the child to advance with his class, necessitates repetition of his grade work, and becomes an economic question of serious importance to the ratepayer. The cost of re-education in Bridgeport in 1912 was 42% of the entire budget, and for 1918 only 1 7 %. Among the 20,900 children under observation in the schools of Bridgeport, 98% had various forms and degrees of malocclusion of the dentures, a condition now generally recognized as associated with asymmetrical develop ment of the bones of the face and the brain case. Many children with malocclusion owing to the arrested development of the facial and cranial bones suffer from impeded nasal respiration, and develop adenoids and tonsilar hypertrophy, leading to infection with its systemic sequelae and the interferences with bodily nutrition incident to insufficient oxidation of the blood. Ortho dontic treatment for the correction of malocclusion in children is a therapeutic and prophylactic measure having an important health relation rather than a procedure for the relief of deformity.

During the World War bad teeth were so serious a bar to re cruiting that the matter called for attention in all armies. Every where the dental service was increased. In 192I Great Britain created a definite Army Dental Corps, but in the United States such a corps had been formed some years earlier.

National Dental Service.

Undoubtedly the most notable example of comprehensive planning for the national extension of dentistry and oral hygiene as a factor of the public health service is that proposed in the interim report on the Future Provision of Medical and Allied Services, made to the British Ministry of Health by the Consultative Council on Medical and Allied Serv ices, May 1920. This report recognizes oral hygiene and dental service as factors of public health and as proper subjects for control and development by the State.

Personal Hygiene.

To establish the habit of personal care of the mouth in school children is a field of activity that has de veloped the specially trained dental nurse or hygienist as an ad juvant to dental service, whose calling is now legalized in the principal States of the United States. The work of the dental nurse is limited to the treatment of the exposed surfaces of the teeth, in the removal of deposits and accretions thereon, the train ing of school children in the systematic use of the tooth-brush and their education in the importance of mouth cleanliness.

War Surgery.

The many head, face and jaw wounds during the World War created a new field for oral surgery and surgical prosthesis. Surgical measures alone were insufficient for success ful treatment, as the loss of tissue from gunshot wounds of the head and face, and scars resulting from extensive lesions left the patient in many instances with repulsive deformities. The re sources of surgery and dentistry were called into co-operation and the aid of dental prosthetic technique was often necessary.

Oral Prophylaxis.

Oral prophylaxis, in so far as it has been instrumental in securing cleanliness of the mouth and teeth, has undoubtedly prevented dental disease to a considerable degree, but has not been wholly effective. As research has thrown light upon dental disease, attention has been increasingly focused upon means for its prevention. The factors of susceptibility and im munity are undergoing active investigation, with strong indica tions that nutritional errors and faulty metabolism play a role of primary importance in the causation of dental disease. Cor rection of faulty food habits and a rational hygiene should con tribute materially toward the prevention of caries and perio dontal necrosis, the most common and widely distributed of hu man disorders. Because of the recognition of the vital relations of the teeth, the dental educational system, through a rapid reor ganization, is proceeding toward a more efficient adaptation of the knowledge of health relations of the teeth to the ends of dental practice.A systematic survey of the whole field of dental education has been made by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, with a view to recommending such adjustments as will bring systematic dental education fully up to the standard of present requirements from a public health standpoint.

General Developments.

While the most conspicuous prog ress in dentistry since 1910 has been ir the direction of its vital and hygienic relations, its technical and engineering features have shown a similar development. Until this period the construction of artificial dentures for the prosthetic restoration of lost teeth was almost wholly an empirical procedure depending on the judgment, manual skill and good taste of the operator. Scientific studies of the engineering principles underlying the mechanism of the human masticatory function, initiated about 1866 by F. H. Balkwill, have since then been prosecuted by numerous fol lowers, who have brought the knowledge of masticatory move ments and of the relations of the teeth and their morsal surfaces thereto to a state of completeness that enables the prosthetist, by the aid of mechanical articulating devices, to reproduce in the artificial denture a mechanism with possibilities approximat ing, both functionally and artistically, those of natural dentures.The entire development of modern dentistry dates from the century, and mainly from its latter half. Beginning with a few practitioners and no organized professional basis, educa tional system or literature, many thousands of its practitioners are, at the present time, to be found in all civilized communities. Its educational institutions are numerous and well equipped. It possesses a large periodical and standard literature in all lan guages. Its practice is regulated by legislative enactment in all countries in the same way as medical practice. The business of manufacturing and selling dentists' supplies represents an enor mous industry, in which millions of capital are invested.

F. Litch, American System of Dentistry; Julius Scheff, jun., Handbuch der Zahnheilkunde; Charles J. Essig, American Text-Book of Prosthetic Dentistry; Tomes, Dental Anatomy and Dental Surgery; W. D. Miller, Microorganisms of the Human Mouth; Hopewell Smith, Dental Microscopy; H. H. Burchard, Dental Path ology, Therapeutics and Pharmacology; F. J. S. Gorgas, Dental Medi cine; E. H. Angle, Treatment of Malocclusion of the Teeth and Fractures of the Maxillae; G. Evans, A Practical Treatise on Artificial Crown-and-Bridge Work and Porcelain Dental Art; C. N. Johnson, Principles and Practice of Filling Teeth, American Text-Book of Operative Dentistry (3rd ed., 19o5) ; Edward C. Kirk, Principles and Practice of Operative Dentistry (2nd ed., 1905) ; J. S. Marshall, American Text-Book of Prosthetic Dentistry (edited by C. R. Turner; 3rd ed., 1907) . (E. C. K.)