Dervish

DERVISH, a Persian word, meaning "beggar"; generally in Islam a member of a religious fraternity, whether mendicant or not ; but in Turkey and Persia more exactly a wandering, begging religious, called, in Arabic-speaking countries, a faqir. With im portant differences, the dervish fraternities may be compared to the regular religious orders of Roman Christendom, while the Ulama (q.v.) are, also with important differences, like the secular clergy. For the origin and history of the mystical life in Islam, which led to the growth of the order of dervishes see SUFI`ISM ; here an account is given of (I) the dervish fraternities, and (2) the Sufi hierarchy.

1. The Dervish Fraternities.

In the earlier times, the rela tion between devotees was that of master and pupil. Those in clined to the spiritual life gathered round the revered shaykh (mar shid, "guide," ustadh, pir, "teacher"), lived with him, shared his religious practices and were instructed by him. In time of war against the unbelievers, they might accompany him to the threat ened frontier, and fight under his eye. Thus murabit, "one who pickets his horse on a hostile frontier," has become the marabout (q.v.) or dervish of Algeria; and ribat, "a frontier fort," has come to mean a monastery. The relation, also, might be for a time only. The pupil might at any time return to the world, when his reli gious education and training were complete. Continuous corpora tions began to be formed in the 12th century. Many existing orders trace their origin to saints of the 3rd, 2nd and even st Muslim centuries, e.g., to either `Ali or Ab Bakr, and in Egypt all are under the rule of a direct descendant of the latter, but such ascription is purely legendary.

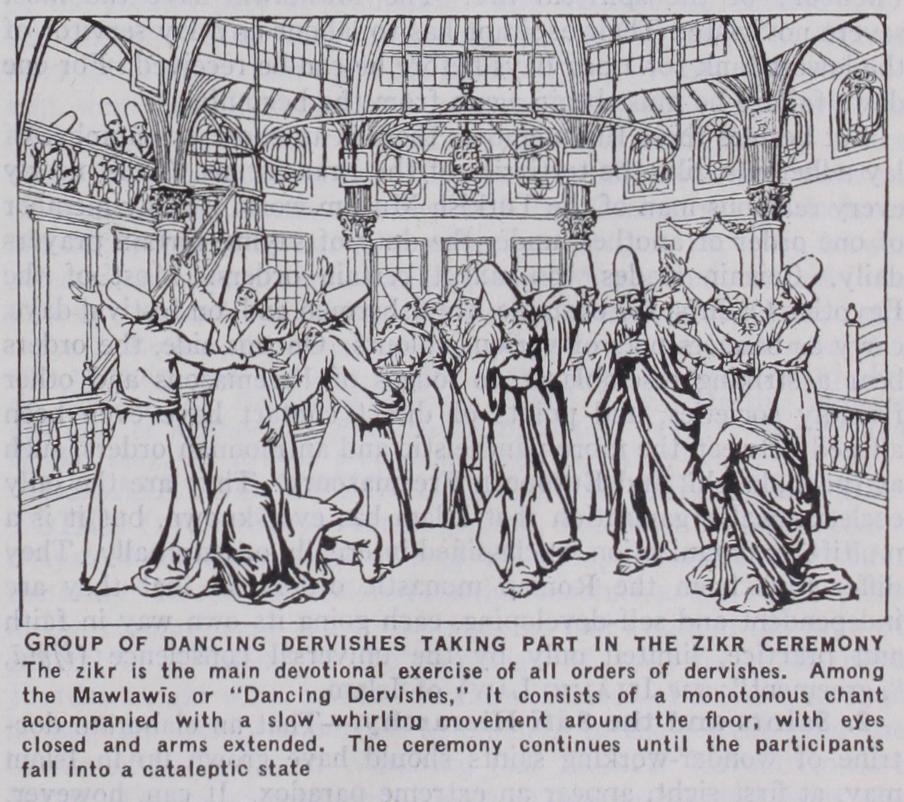

Of these orders, 32 are commonly reckoned, but many have vanished or have been suppressed, and there are sub-orders in numerable. Each has a "rule" dating back to its founder, and a ritual which the members perform when they meet together in their convent (khanqdh, zdwiya, takiya). This may consist simply in the repetition of sacred phrases, or it may be an elaborate per formance, such as the whirlings of the dancing dervishes, the Mawlawis, an order founded by Jalal ud-Din ar-Rumi, the most broad-minded and tolerant of all. There are also the performances of the RifTis or "howling dervishes." In ecstasy they cut them selves with knives, eat live coals and glass, handle red-hot iron and devour serpents. They profess miraculous healing powers, and the head of the Sa'dis, a sub-order, used, in Cairo, to ride over the bodies of his dervishes without hurting them, the so-called Daseh (dausa). Another division is made by their attitude to the law of Islam. Some neglect in general the ceremonial and ritual law, to such an extent that in Persia, India and Turkey dervish orders are classified as ba-share, "with law," and bi-shart, "without law." The latter are really antinomians, and the best example of them is the Baktashi order, widely spread and influential in Tur key and Albania and connected by legend with the origin of the Janissaries. The Sanusi was the last order to appear, and is dis tinguished from the others by a severely puritanic and reforming attitude and strict orthodoxy, without any admixture of mystical slackness in faith or conduct. Each order is distinguished by a peculiar garb. Candidates for admission have to pass through a noviciate, more or less lengthy. First comes the (and, or initial covenant, in which the neophyte or murid, "seeker," repents of his past sins and takes the shaykh of the order he enters as his guide (murshid) f or the future. He then enters upon a course of instruction and discipline, called a "path" (tariqa), on which he advances through diverse "stations" (maqamat) or "passes" Caqabeit) of the spiritual life. The Mawlawis have the most severe noviciate. Their aspirant has to labour as a lay servitor of the lowest rank for i,00i days before he can be received. For one day's failure he must begin again from the beginning.

But besides these full members there is an enormous number of lay adherents, like the tertiaries of the Franciscans. Thus, nearly every religious man of the Turkish Muslim world is a lay member of one order or another, under the duty of saying certain prayers daily. Certain trades, too, affect certain orders. Most of the Egyptian Qadiris, for example, are fishermen and, on festival days, carry as banners nets of various colours. On this side, the orders bear a striking resemblance to lodges of Freemasons and other friendly societies, and points of direct contact have even been alleged between the more pantheistic and antinomian orders, such as the Bakta.shi, and European Freemasonry. They are the only ecclesiastical organization that Islam has ever known, but it is a multiform organization, unclassified internally or externally. They differ thus from the Roman monastic orders, in that they are independent and self-developing, each going its own way in faith and practice, limited only by the universal conscience (ijmii, "agreement": see ISLAMIC LAW) of Islam.

2. Saints and the Stifi Hierarchy.

That an elaborate doc trine of wonder-working saints should have grown up in Islam may, at first sight, appear an extreme paradox. It can, however, be conditioned and explained. First, Muhammad left undoubted loop-holes for a minor inspiration, legitimate and illegitimate. Secondly, the Sufis, under various foreign influences, developed these to the fullest. Thirdly, just as the Christian church has ab sorbed much of the mythology of the supposed exterminated heathen religions into its cult of local saints, so Islam, to an even higher degree, has been overlaid and almost buried by the super stitions of the peoples to which it has gone. Their religious and legal customs have completely overcome the direct commands of the Qur'an, the traditions from Muhammad and even the "Agree ment" of the rest of the Muslim world (see InAmic LAw). The worship of saints, therefore, has appeared everywhere in Islam, with an absolute belief in their miracles and in the value of their intercession, living or dead.Further, there appeared very early in Islam a belief that there was always in existence some individual in direct intercourse with God and having the right and duty of teaching and ruling all man kind. This individual might be visible or invisible; his right to rule continued. This is the basis of the Ismaili and Shi'i positions (see the article IsLamic INSTITUTIONS). The Sufis applied this idea of divine right to the doctrine of saints, and developed it into the Sufi hierarchy. This is a single, great, invisible organization, forming a saintly board of administration, by which the invisible government of the world is supposed to be carried on. Its head is called the Qutb (Axis) ; he is presumably the greatest saint of the time, is chosen by God for the office and given greater miracu lous powers and rights of intercession than any other saint enjoys. He wanders through the world, often invisible and always un known, performing the duties of his office. Under him there is an elaborate organization of walls, of different ranks and powers, according to their sanctity and faith. The term wali is applied to a saint because of Kor. x. 63, "Ho! the walls of God; there is no fear upon them, nor do they grieve," where wali means "one who is near," friend or favourite.

In the fraternities, then, all are dervishes, cloistered or lay ; those whose faith is so great that God has given them miraculous powers—and there are many—are walis ; begging friars are fakirs. All forms of life—solitary, monastic, secular, celibate, married, wandering, stationary, ascetic, free—are open. Their theology is some form of Siafi'ism.