Design

DESIGN is the arrangement of lines or forms which make up the plan of a work of art with especial regard to the pro portions, structure, movement and beauty of line of the whole. A design may be naturalistic or wholly the abstract conception of the artist. Its structure is related to the structure of the frame and the rendering of the subject, but not to the structure or anatomy of the subject itself. A design may be successful which is incorrect in every detail of anatomy. Design in one sense is synonymous with composition, and has to do with all the arts, though more pronounced in the applied arts than in the fine arts.

The Japanese artist Korin arrived at much of his design through the selection of certain parts of purely natural arrange ments which were simplified and selected as typical, but which were rendered in a naturalistic manner. Much of modern design is not so made up, but consists of gross distortion for the over stressing of structure or movement, with a complete loss of other characteristics. This type of design is so close to caricature that it often detracts rather than adds to the beauty of a work of art.

Design is concerned not only with typical movement but also with typical rhythms. Through the medium of parallel master strokes or accenting of repeating movements, rhythms are set up which should, like the rhythms of great poetry, accent the meaning and express a crystallization of the personality of the artist, and at the same time of his subject as seen through his eyes. Just as in "The Raven" by Poe, we have the summing up of all of Poe's mood in his work and at the same time have the summing up of the expression of all human despair in the bird's recurring "Never more," so in the design of a master of the graphic arts will be found accents and rhythms which build the mood he wishes to establish. Design is to the graphic arts what verse form and rhyme are to poetry: the ladder up which it climbs to the heights. Design can exist without colour, but just as there can be design in line and mass so there can also be design in colour, based upon the distribution of harmoniously blending or contrasting tones; when design is present in both line and colour the two must work together to further the effect of the concep tion. Every element of art can be designed separately and in relation to the other elements. Thus there can be structural de sign, movement design, outline design. (See DRAWING.) Teaching.—In the teaching of design it is often helpful to have the student cut out various pieces of paper representing the main areas to be used and move them about within the size area, cut out of the centre of another piece of paper, upon which he is to work. When these have been arranged to his satisfaction, lines should be thrown in which tie the whole together; and finally, with these established areas and lines to guide him, work can be begun. The Chinese artist does this mentally as he sits contemplating the silk upon which he is to paint, for he has trained his mind to remember the arrangement once he has de cided upon it. The student can teach himself to do this, but it is well to begin with the more objective method.

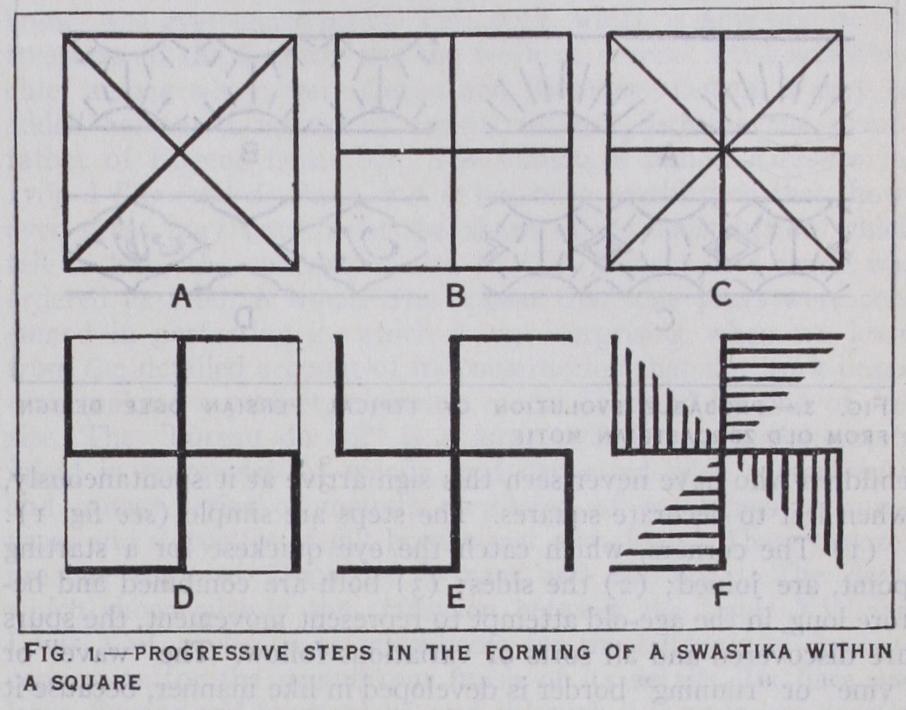

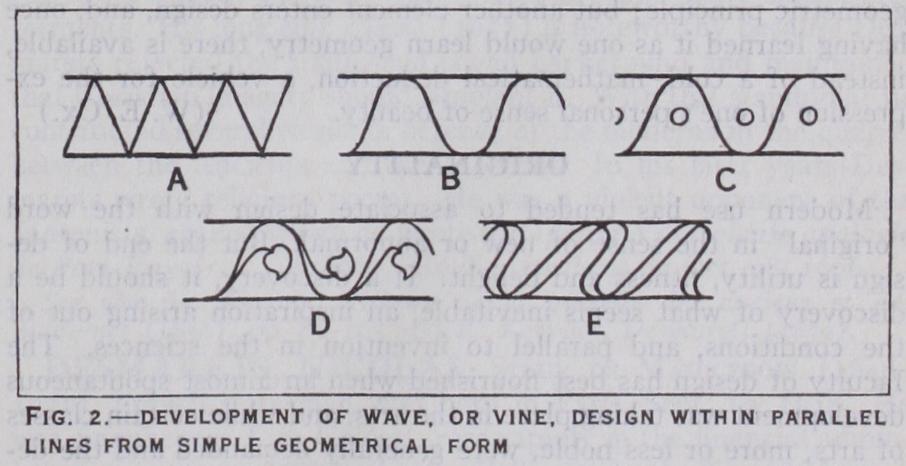

It is interesting to note that in given areas only a certain num ber of effective designs are possible, and that man has hit upon them in every part of the world without intercommunication. Scientists have tried to prove a common origin for the race be cause of the almost universal use of the swastika, but many children who have never seen this sign arrive at it spontaneously, when left to decorate squares. The steps are simple (see fig. 1) : (I) The corners, which catch the eye quickest for a starting point, are joined; (2) the sides; (3) both are combined and be fore long, in the age-old attempt to represent movement, the spurs are discovered and all sorts of variations follow. The "wave" or "vine" or "running" border is developed in like manner, because it is the most obvious way to decorate a narrow space between paral lel lines. We usually find (A) the geometrical treatment (fig. 2) ; (B) the curve with open areas which are soon (C) filled with spots assuming the shape of leaves on a vine as time goes on (D), and an excuse for their being is demanded. Finally, as in (E), the movement is increased and it becomes on many Tzu Chow vases of China a leaping rather than a running border, repre sentative of waves from which the fiery dragon ascends.

Development.

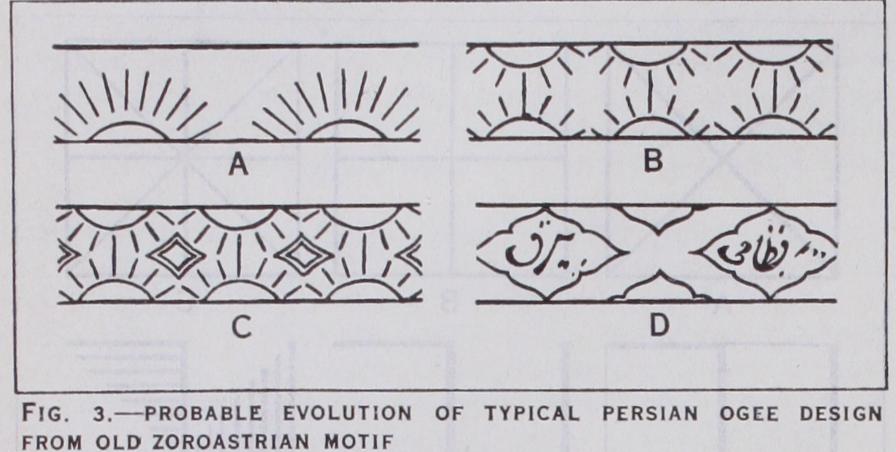

The typical Persian ogee design has an in teresting origin which is demonstrable on existing vases. In fig. 3 (A) is shown the old Zoroastrian motif of the rising sun which only loosely filled the border; other suns were introduced at a still earlier period. In a further attempt to build the border to gether a design was inserted between them, which sometimes held written characters and finally, as the religion is developed, the suns disappear and ogee patterns are fitted together, becoming a typical national motif.Design is, therefore, old and has been thought of for many thousand years, and the student does well to acquaint himself with early examples found in various parts of the world. It is almost as difficult to create a new design as it is to discover a new geometric principle; but another element enters design, and, once having learned it as one would learn geometry, there is available, instead of a cold, mathematical deduction, a vehicle for the ex pression of one's personal sense of beauty. (W. E. Cx.) Modern use has tended to associate design with the word "original" in the sense of new or abnormal. But the end of de sign is utility, fitness and delight. If a discovery, it should be a discovery of what seems inevitable, an inspiration arising out of the conditions, and parallel to invention in the sciences. The faculty of design has best flourished when an almost spontaneous development was taking place in the arts, and while certain classes of arts, more or less noble, were generally demanded and the de mand copiously satisfied, as in the production of Chinese porcelain, Greek vases, Byzantine mosaics, Gothic cathedrals and Renais sance paintings. Thus where a "school of design" arises there is much general likeness in the products but also a general progress. The common experience—"tradition"—is a part of each artist's stock in trade; and all are carried along in a stream of continuous exploration. Some of the arts, writing, for instance, have been little touched by conscious originality in design, all has been progress, or, at least, change, in response to conditions. Under such a system, in a time of progress, the proper limitations react as intensity; when limitations are removed the designer has less and less upon which to react, and unconditioned liberty gives him nothing at all to lean on. Design is response to needs, conditions and aspirations. The Greeks so well understood this that they appear to have consciously restrained themselves to the develop ment of selected types, not only in architecture and literature, but in domestic arts, like pottery. Design with them was less the new than the true.

For the production of a school of design it is necessary that there should be a, considerable body of artists working together, and a large demand from a sympathetic public. A process of continuous development is thus brought into being which sustains the individual effort. It is necessary for the designer to know familiarly the processes, the materials and the skilful use of the tools involved in the productions of a given art, and properly only one who practises a craft can design for it. It is necessary to enter into the traditions of the art, that is, to know past achievements. It is necessary, further, to be in relation with nature, the great reservoir of ideas, for it is from it that fresh thought will flow into all forms of art. These conditions being granted, the best and most useful meaning we can give to the word design is exploration, experiment, consideration of possi bilities. Putting too high a value on originality other than this is to restrict natural growth from vital roots, in which true original ity consists. To take design in architecture as an example, we have rested too much on definite precedent (a different thing from living tradition) and, on the other hand, hoped too much from newness. Exploration of the possibilities in arches, vaults, domes and the like, as a chemist or a mathematician explores, is little accepted as a method in architecture at this time, although in antiquity it was by such means that the great master-works were produced : the Pantheon, Santa Sophia, Durham and Amiens cathedrals. The same is true of all forms of design. Of course the genius and inspiration of the individual artist is not here ignored, but assumed. What we are concerned with is a mode of thought which shall make it most fruitful. See ARTS AND