Destructors

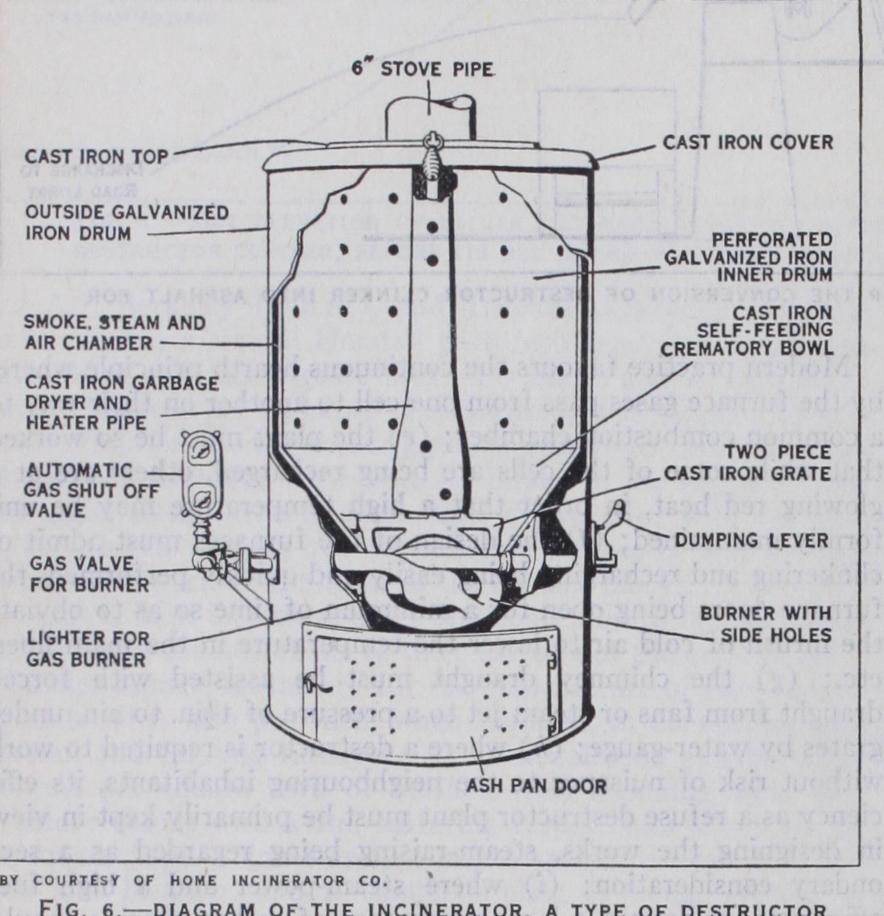

DESTRUCTORS. This term is applied, particularly in England, by municipal engineers, to a battery of high-temperature furnaces constructed for disposing, by burning, of household and town refuse. Messrs. Manlove, Alliott and Co., of Nottingham first registered the word destructor as their special trade name for such a furnace. (For developments in the United States, see REFUSE DISPOSAL.) The first destructor built by this firm under Fryer's patent was erected in Manchester in 1874. Disposal of refuse is not, however, the only consideration. Utilization of refuse as fuel for steam production is also important. Many towns systematically utilize the calorific value of refuse.

A proper degree of caution, however, should be exercised when contemplating the use of refuse as a low grade fuel. When its value for this purpose was first recognized it was believed that the refuse of a given population was of itself sufficient to develop the necessary steam-power for supplying that population with their electric lighting requirements. The supposed economic importance of a combined destructor and electric undertaking of this character possibly had much to do, in some districts, with the development both of the adoption of the principle of dealing with refuse by fire and of lighting by electricity. Engineering expe rience, however, very often has shown this to be impractical. But, under favourable circumstances, determining the merits in each case, useful service to other power-using undertakings, such as sewage pumping, clinker crushing plants, etc., may be obtained.

Composition of Refuse.—The composition of house-refuse, which obviously affects its calorific value, varies widely in dif ferent districts. The following is an analysis of refuse as dealt with in destructors, based on the average of 12 towns in Great Britain. The percentages of the various constituents are as fol lows :—fine dust 45.45, tin. to and large cinders 36.16, bricks, pots, shale, etc., 6.5, tins 1.3, rags .S4, glass .83, bones •o9, vege table refuse 4•05, scrap iron •42, paper 2.26, fish offal, greens, small paper bags, carpet, oil cloth, boots, etc., 2.4 per cent.

In London, the quantity of house-refuse amounts approximately to from 4cwt. to 5 cwt. per head per annum, or to from 200 to 250 tons per i,000 of the population per annum. Statistics, however, vary widely in different districts. At Ipswich 7.5cwt. per I,000 of the population per working day are collected, whereas, at Merthyr Tydfil 40•I cwt. per 1,000 people per day are produced. Recent data show the normal quantity collected to lie between 15 and 2ocwt. per i,000 people per day. When estimating the required capacity of a destructor plant, the quantity of refuse produced by the particular town in question must first be independently in vestigated, and all calculations based accordingly.

A cubic yard of ordinary house-refuse weighs from 12 to 15cwt. but varies according to its condition whether wet or dry, etc. Shop refuse often consists largely of paper, packings, straw and cardboard. Its weight may be as little as 7cwt. per cubic yard.

Methods of Disposal.—Various methods of disposal of refuse are adopted by different towns according to local facilities and conditions. Owing to the high costs involved since the World War in the working of refuse destructors, a system of controlled tipping upon suitable land has been largely resorted to, notably at Bradford, where some 45 tips within the city boundaries are in use. The refuse is spread in layers of about 8f t. in depth and regularly covered with soil. By this means waste land, old quar ries, etc., are reclaimed for future use as parks and open spaces. Pulverization of refuse has been adopted in some towns. The refuse is crushed to a small gauge, and where possible disposed of as manure, but the difficulty of securing a reliable market is usually considerable. When obtained such markets are not to be relied upon with any certainty of continuity. Another means of disposal is by the separation or salvage system. In this case the dust, cinders, paper, rags, glass, metals, tins, etc., are all sepa rately sorted out and sold where markets can be found. The vege table and other putrescible constituents are burned. The handling and redistribution of refuse material in this way amongst the population cannot be regarded . with favour in the interests of public health. Disposal at sea and sinking in deep water are also practised, but is often rather costly and sometimes unsatisfactory.

The Destructor System.—The destructor system in which the refuse is burned to an innocuous clinker in specially constructed high-temperature furnaces is that which is most generally resorted to when other methods have proved unsatisfactory, especially in districts which have become well built up and thickly populated. Conditions regarding this method of disposal have, however, changed materially during recent years, particularly in reference to the present high capital costs and greatly increased working expenses. There has also been an appreciable deterioration in the calorific value of present-day refuse in many districts. These conditions have increased the difficulty of usefully combining a destructor with some form of power-using undertaking, with the object of earning credits as a set-off against the heavy working expenses of a destructor installation. The greatly extended use of electric and gas fires, improved types of oil and slow-combustion heating stoves, the high price of coal and the more economical habits of householders, have all contributed to the production of house refuse with a smaller proportion of cinders and scraps of coal, thereby resulting in a low calorific value, and also a poorer qual ity of clinker from the destructor furnace. At Farnborough it is found that the calorific value of refuse is now about 50% less than in pre-war days, and there has been similar experience at Southampton, Hull and elsewhere.

Many of the earlier destructor and electricity station com binations have not proved satisfactory for various reasons, and have been abandoned. One difficulty often experienced has been that of maintaining a steady and reliable steam pressure with so variable and uncertain a fuel.

A number of destructor-electric combinations are, however, working satisfactorily in districts where the local conditions are favourable, as at Rhondda, Wolverhampton and Pontypridd. At Rhondda and Pontypridd the refuse is of a high calorific value, and contains a relatively large percentage of small coal and un burnt cinders. During an official test, the Rhondda destructor (Heenan and Froude) evaporated 4.15 lb. of water per I lb. of refuse burned from and at 212°. This destructor was erected in 1915, and the South Wales Power Co. purchased the electric current produced at this installation. The electrical energy gen erated is equal to 264 units per ton of refuse burnt.

The electrical output at the Rhondda destructor plant has not been equalled by any combined destructor and electric station. Other power-using services to which the surplus heat from a destructor is applied include the pumping of low level sewage, as carried out at Salisbury, Lincoln, Cambridge, Watford, East bourne, Luton, Felixstowe, Aldershot and Twickenham.

During recent years, the question of high running costs at destructor installations has been under careful review by many British public authorities, and many destructors have either been discontinued or rendered of limited service.

Conditions for Destructor Syste.

As regards the general question of the advisability or otherwise of erecting a destructor, each town should decide for itself, according to the local condi tions and requirements. It is a question upon which it is unwise to generalize, but when considering the matter, some leading points to be kept in view are: (a) Is the district so closely built up and congested as to render all other less costly means of dis posal impracticable, thus rendering the expense of a destructor necessary as a last resort? (b) Has the refuse sufficient calorific value to justify its use for steam-raising purposes, and are there any necessary local services, such as sewage pumping, upon which the heat from the destructor can be profitably utilized, and thus save the cost of coal as a set-off against the heavy working expenses? (c) Are any local markets available for the sale of surplus clinker, tins, etc.? (d) Can a suitable central site for a destructor be found in a populated area without involving addi tional expense in haulage to some outlying site, or causing nuisance from smells, dust, and the concentrated cartage of refuse, to the neighbouring inhabitants? (e) Can the existing sys tem of disposal be carried on without risk of real danger (as dis tinguished from sentiment) to the public health? If not, the in stallation of a destructor must then be seriously considered.Although the conditions arising out of the World War placed a check in Great Britain, in the United States and on the Con tinent upon the laying down of new destructor installations, and the maintenance of existing plants, the past few years have shown a renewal of activity in this direction.

Notwithstanding high capital costs and working expenses, necessity arising out of local conditions has led to the erection of new plants at Birmingham, Hornsey, Devonport, ROchdale, Wimbledon, Portsmouth, Brighton, Llandudno, East Ham, Hast ings, Leicester, Leeds, Hereford, Accrington, Coventry, Edin burgh, Perth, Stoke, New York, Gibraltar and elsewhere.

Modern Equipment.

A modern installation usually includes, in addition to the leading feature of the destructor cells or furnaces, a mechanical power-driven plant used in connection with the preliminary screening of the refuse and comprising screens, elevators, etc., for the removal of dust up to about iin. gauge, an overhead runway for conveyance of hot clinkers from the furnace mouths, and storage accommodation for raw refuse for use when the collectors are not at work.For the removal of tins and iron from the raw refuse electro magnetic separators are frequently installed where these materials have a marketable value. The tins are reduced in bulk to con venient blocks by means of a hydraulic baling-press. Clinker from the furnaces is reduced to saleable form by suitable clinker crushing and screening plants. Other accessory machinery in cludes a strongly built mortar mill and a hydraulic press for the manufacture of slab-paving in order to utilize the surplus clinker, a power-driven fan with air-ducts for the supply of forced draught to the cells. Machinery for the manufacture of asphalt from clinker for the surfacing of roadways is in some cases also installed, as, e.g., at Brighton and Abertillery. The motive-power for actuating all this accessory plant at the destructor station, including an electric lighting equipment, is usually economically obtainable from the surplus heat from the cells when applied to the generation of steam in a suitable boiler.

Forced Draught.

The f orced draught to destructor cells may be given by an air fan or by steam blast. The air fan will require to work at about 6in. total water-gauge pressure, and to give from 2in. to 3in. of pressure in the ashpit itself. The actual pressure will vary according to the thickness of the fires being burnt at any given time. The power required to drive the air fan suitable for six furnaces of the Sterling type (New Destructor Co., Ltd.) will not exceed 25 brake horse-power.In the case of steam blast with 2in. to 21in. water-gauge pres sure in the ashpit, the quantity of steam used per hour would be approximately I,000 lb. in four Heenan cells, or 25o lb. of steam per hour per grate of 3osq.ft. area. The temperature required to be developed in the combustion chamber is approximately 2,000°. The advantages of forced draught are that a much higher tem perature is attained, little more air than the quantity theoretically necessary is needed, and the minimum amount of cold air is ad mitted to the furnaces. The air supply to modern furnaces is usually delivered hot—the inlet-air being first passed through an air-heater the temperature of which is maintained by the waste heat in the main flue.

Types of Cells.

The evolution of a good type of destructor cell or furnace, has occupied many years of experience, and has been the subject of much experiment and many failures. The principal towns in England which took the lead in the adoption of the destructor were Manchester, Birmingham, Leeds, Warring ton, Blackburn, Bradford, Bury, Hull, Nottingham, Ealing and London. Ordinary furnaces, built mostly by dust contractors, began to come into use in London and in the north of England in the second half of the r9th century, but they were not scientifi cally adapted to the purpose, and necessitated the admixture of coal with the refuse to ensure its proper cremation.The Manchester Corporation erected a furnace of this kind about the year 1873-74, and Messrs. Mead and Co. made an un satisfactory attempt in 187o to burn house-refuse in closed furnaces at Paddington. Shortly after Alfred Fryer erected his destructor at Manchester, several other towns also adopted this furnace. Other types were from time to time brought before the public, among which may be mentioned those of Pearce and Lup ton, Pickard, Healey, Whiley, Thwaite, Young, Wilkinson, Burton, Hardie, Jacobs and Ogden. In addition to these the Beehive and the Nelson destructors became well known. The former was in troduced by Stafford and Pearson of Burnley, and one was built in 1884 in the parish yard at Richmond, Surrey, but the results being unsatisfactory, it was closed during the following year. The Nelson furnace, patented in 1885 by Messrs. Richmond and Birtwistle, was erected at Nelson-in-Marsden, Lancashire, but, being costly in working, was abandoned.

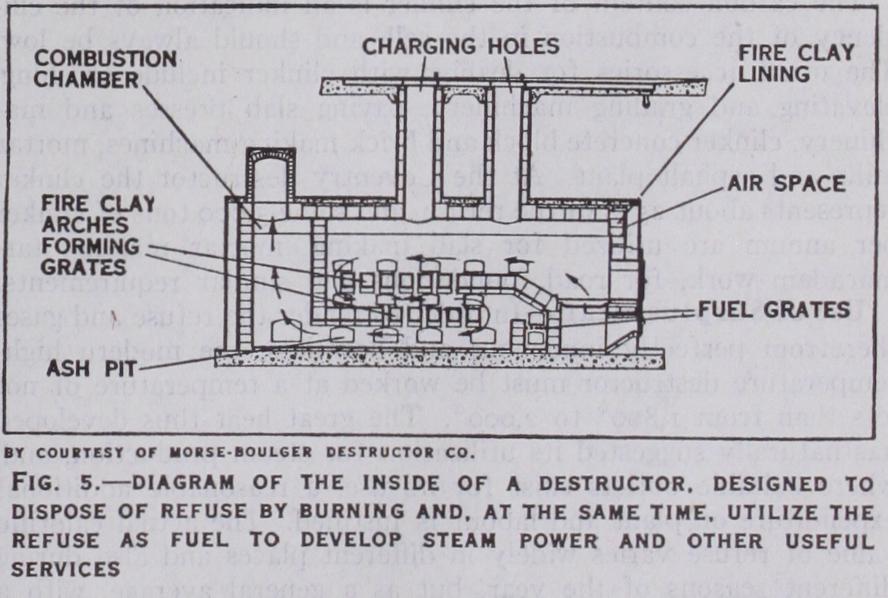

Types of Destructors.

The principal types of destructors now in use are those of Fryer, Warner, Manlove-Alliott, Mel drum, Beamen and Deas, Heenan and Froude, and the Horsfali and Sterling destructor. The Fryer destructor was patented by Alfred Fryer in 1876. The cells are usually arranged in pairs back to back, and enclosed in a rectangular block of brickwork having a flat top on which the house-refuse is tipped from the carts. The furnace burns from four to six tons of refuse per cell per 24 hours. The outlets for the products of combustion are placed at the back near the refuse feed openings. This arrangement is im perfect in design as it permits offensive vapours from unburnt refuse to escape into the main flue with the products of com bustion. Nuisances from smell arising from this cause led, in some instances, to the introduction of a secondary furnace, known as a cremator, which was patented by C. Jones of Ealing in 1885. This furnace was placed in the main flue leading to the chimney shaft for the purpose of cremating the organic matters in the vapours from the unburnt refuse, but it added considerably to the cost of running the destructor and was abandoned. The Fryer destructor, with a cremator, was largely used during the early history of destructors, but it has given place to more mod ern and improved designs of high temperature furnaces.The Horsfall destructor is a high-temperature furnace of later design than the foregoing. Important improvements are to be found in the arrangement of the flues and flue outlets for the products of combustion, and in the provision of a forced draught duct through which air is supplied under pressure into a closed ashpit. The flue opening for the removal of gaseous products of combustion is placed at the front of the furnace over the dead plate whilst the feeding-hole for the raw refuse is situated at the back of and above the furnace. By these means the gases from the raw refuse must pass, on their way to the main flue, over the hottest part of the furnace and through the flue opening in the red-hot reverberatory arch. By means of the forced draught, a temperature of from i,5oo° to 2,000°, as tested by a thermo electric pyrometer, is attained in the main flue. Cast-iron boxes are provided at the sides of the furnaces, and through these the forced draught is conveyed on its way to the fire grate. The boxes are also designed to prevent the adhesion of clinker to the side walls of the cells and so to preserve the brickwork.

The standard arrangement for a modern Manlove-Alliott top feed destructor is designed on the "continuous hearth" principle whereby the furnace gases pass from cell to cell on their way to the combustion chamber, thus ensuring a uniform temperature and minimising the cooling down effect when fresh refuse is charged into the furnaces. A joint destructor and sewage pump ing scheme has been installed by the Borough of Guildford and the Rural District Council of Hambledon, in which sewage is raised by pneumatic ejectors worked by steam from the refuse. There are f our cells of the top-feed type arranged with two water-tube boilers on the Wood and Brodie "Unit" system. Each boiler is sandwiched between a pair of cells, and the high-temperature gases pass immediately into contact with the boiler heating sur face. There are eight ejector stations, in each of which two ejec tors work as a pair, arranged so that both ejectors cannot be filling or discharging at the same time. The ejectors are of the Alliott and Philps's automatic improved type.

Warner's destructor (the "Perfectus") was similar to Fryer's in general arrangement, but was provided with special charging hoppers, dampers in flues, dust-catching arrangements, rocking grate bars, and other improvements. The refuse was tipped into feeding-hoppers, consisting of rectangular cast-iron boxes over which plates were placed to prevent the escape of smoke and fumes. When refuse was fed into the furnace a flap-door con trolled by a lever was thrown over, the contents of the hopper dropped on to the sloping fire-brick hearth beneath, and the door at once closed again to prevent the admission of cold air into the furnace as far as possible. The cells were each 5ft. wide by I 'ft. deep. The rear portion consisted of a fire-brick drying hearth, and the front of rocking grate bars upon which the com bustion took place. The amount of refuse consumed varied from five to eight tons per cell per 24 hours.

The Meldrum "Simplex" destructor produced good steam rais ing results and was first installed at Rochdale, Hereford, Darwen, Nelson, Plumstead and Woolwich. Cells have also been erected at Burton, Hunstanton, Blackburn, Burnley, Cleckheaton, Lan caster, Sheerness and Weymouth. This destructor differs from those previously described in general arrangement. The fire grates are placed side by side without separation except by dead plates, but, in order to localize the forced draught, the ashpit is divided into parts corresponding with the different grate areas. Each ashpit is closed airtight by a cast-iron plate, and is provided with an airtight door for removing the fine ash. Two Meldrum steam-jet blowers are provided for each furnace, supplying any required pressure of blast up to 6in. water column. The pressure usually used is about i z to 2 inches. The furnaces are designed for hand-feeding from the front, but hopper-feeding can be applied if preferred. The products of combustion are led from the back of each fire grate into a common flue leading to the boilers sand to the chimney shaft, or are conveyed sideways over the various grates and a common fire-bridge to the boilers or chimney. The heat in the gases, after passing the boilers, is still further used to heat the air supplied to the furnaces—the gases being passed through an air-heater or continuous regenerator con sisting of a number of cast-iron pipes from which the air is de livered through the Meldrum blowers at a temperature of about 300°. At Rochdale, the Meldrum furnaces consumed from 53 lb. to 66 lb. of refuse per square foot of grate area per hour, as com pared with 22.4 lb. per square foot in a low-temperature destruc tor burning six tons per cell per 24 hours with a grate-area of 25 square feet. The evaporative efficiency varied from 1.39 lb. to 1.87 lb. of water (actual) per i lb. of refuse burned, and the average steam pressure was about i 14 lb. per square inch.

The Beaman and Deas destructor was installed at Warrington, Dewsbury, Leyton, Canterbury, Llandudno, Colne, Streatham, Rotherhithe, Wimbledon, Bolton and elsewhere. At Leyton, which, at the date when this destructor was installed, had a popu lation of over i oo,000, an eight-cell plant dealt with house refuse and filter press cakes of sewage sludge from the sewage disposal works adjoining. Each cell burnt about 16 tons of the mixture in 24 hours and developed about 35 i.h.p. continuously, at an average steam pressure in the boilers of i o5 lb. The essen tial features of this destructor include a level fire-grate with ordinary type bars spaced only--- in. apart, a high-temperatured combustion chamber of about 2,000° at the back of the cells, a closed ashpit with forced draught, provision for the admission of a secondary air supply at the fire-bridge, and a fire-brick hearth sloping at an angle of about 5 2 ° . The forced draught is supplied from fans at a pressure of from i i to tin. of water gauge, and is controlled by means of baffle valves worked by handles on either side of the furnace. The heat from the cells is used in conjunction with a water-tube boiler such as the Babcock and Wilcox, and the gases on their way from the combustion chamber to the main flue pass three times between the boiler tubes. The grate area of each cell is 2 5sq.f t. and the consumption varies from 16 to 20 tons of refuse per cell per 24 hours.

The Heenan destructor has been in use for over 25 years and a large number of installations have been erected in many of the largest cities throughout the world, including Birmingham, Glas gow, London, Leeds, Brussels, Paris, Rotterdam, Leningrad, New York, San Francisco, Montreal, Melbourne, Singapore, Edin burgh, Coventry, and many other places. The essential features of the Heenan System (fig. i) include a continuous furnace chamber with divided ashpits, air heater or regenerator, combus tion and gas mixing chamber, steam generator, forced draught supply with efficient air regulation and a ventilation system.

The cells may be designed for hand-feed under the direct con trol of the eye and hand of the stoker, either on the front-feed or back-feed system, or, where preferred, a system of mechanical charging and clinkering is installed. Mechanical clinkering has involved a change in grate design, and what is known as the trough-gate has been largely employed in the Heenan system. The advantages claimed are : perfect combustion and the maintenance of a regular temperature and boiler pressure during the process of feeding and clinkering; freedom from dust and a minimum of labour in the clinkering operations; the production of a hard clinker practically free from carbon, and a general cleanliness and expedition in the clinkering operations.

By means of the air-heater or regenerator system (placed in the path of the gases after these have passed through the boiler) employed with these furnaces, the thermal efficiency of the fur nace is improved, excess of air in the cells is avoided, and more steady and better steaming results are obtained. Those destruct ors fitted with top-feed are either charged by container feed, skip feed, or feed by conveyor. The mechanical control of the doors permitting the fall of the refuse into the furnace chamber may be by hand operation from the clinkering floor, hydraulic opera tion with ram cylinders on platforms at the level of the top charging doors, or electric motors may be used for the opening and closing of the doors controlled from the clinkering floor.

Furnace doors are air-cooled. When clinkering, provision is made by means of an asbestos preparation to seal the doors to prevent the escape of fumes into the building. During the three years the Coventry Heenan plant was under observation, over 2 lb.

of steam at 16o lb. pressure was produced for every i lb. of refuse burnt, and in colliery districts as much as 4 lb. of steam per i lb. of refuse have been developed from the refuse.

In the London metropolitan area an important installation of the Heenan system was installed at Ilford in 1916, embodying mechanical charging and clinkering accessories. The plant consists of two three-grate (trough-type) units, each unit comprising three mechanically charged and clinkered grates, one Babcock and Wilcox water-tube boiler of 200 lb. per square inch working pressure, one Foster superheater, three electrically operated top charging doors with frames, shafting, drums, pulleys and wire ropes complete, one Heenan fan and engine for forced draught, and two electric cranes for lifting the refuse skips. The steam produced is used to drive generators in an adjoining station. The average rate of evaporation per hour, from and at 212° per square foot heating surface of boiler, under test, was 3.9 lb. The average rate of evaporation per 1 lb. of refuse burnt (from and at 212°) was 1.82 lb., and the steam pressure 155.8 lb. per square inch. The temperature of the combustion chamber was—maxi mum 2,462°, minimum 1,886°.

At a modern installation at Birmingham (Brookvale road depot) a specially designed suction plant was installed to collect waste paper from the end of the conveying belts, and to deliver it free of dust, to baling presses. To facilitate clinker handling, a mono rail or overhead railway, with skips equipped with raising and lowering gear, provides convenient means of transporting the clinker to the cooling area or to the clinker plant.

The Heenan system had been largely used on the Continent, where some of the largest and best equipped installations are to be found. The plant erected at Rotterdam (Holland) in 1912 is a good example.

The refuse disposal plants of the New Destructor Co. include designs on the improved Horsfall and Sterling types. A typical plant is illustrated in fig. 2 showing the handling and path of the refuse from the time it is delivered to the destructor works until its reception into the furnaces. The cells are of modern continuous grate high-temperature type, and equipped for good steam-raising results. The Horsfall Poplar plant yields 70o h.p. from the combustion of the refuse, the power being used for generating electric current. The evaporation per 1 lb. of refuse burnt (from and at 212°) is about 1.5 lb. of water. The Mersey Dock and Harbour Board, Liverpool, use a Horsfall plant yield ing 36oh.p., for lighting, clinker treatment, etc., the capacity of five cells being 13o tons of refuse per 24-hour day. Sterling plants are used at Sydney (N.S.W.), Zurich, Colombo, Pittsburgh (U.S.A.), Berkeley (U.S.A.), and Toronto (Canada). The Co lombo plant is a six-cell Horsfall back-feed type with continuous grate ; each cell has a grate area of 3osq.f t. and is capable of burning ten tons per 24 hours. Forced draught is supplied by two positive blowers of the Roots pattern, exhausted through a gal vanized-iron overhead main with its intake in the hoppers. The foul gases from the refuse are thus drawn over with the cold air and forced through the regenerative air heater and through underground ducts to the front of the furnace blocks. A 6in. cast iron pipe is built into these ducts and connected to the side boxes for delivering the heated air to the underside of the grate bars.

Clinker asphalt machinery for the manufacture of road surfac ing material is also provided, when required, in connection with Horsfall and Sterling furnaces. At an installation at Abertillery the cost per square yard of finished road including 2 tin. base or binder course with a Tin. surfacing carpet costs about 7s. 3d. per square yard. Clinker-asphalt plants are also in use at Wool wich and Hendon, and a complete plant is being erected at Walthamstow.

Beast-cremating Chamber.

This installation includes two beast-cremating chambers to enable cattle, horses, dogs, etc., to be disposed of in the event of cattle murrain breaking out in the city. At the top of the chambers are large cast-iron doors lined with fire-bricks. The doors are fitted with a water seal to prevent hot gases blowing out. Carcasses are hoisted by pulley blocks mounted on a trolley fixed to steel joists so placed as to enable the beast to be lifted from the clinkering floor, traversed over the top of the furnaces to the centre of the cremating chamber, and dropped in by cutting a rope to avoid handling.

Destructor Records and Tests.

To judge correctly of the true performance of a destructor installation it is necessary to take careful observations and tests over long periods. Reliable records of every-day working throughout the whole year are necessary to gain a true knowledge of the performance of the plant. For such tests the destructor station should be provided with a road platform weigh-bridge, water meter, a pyrometer and, if possible, a carbon-dioxide recorder. The principal data to be noted include : the weight and description of refuse burned, the quantity of water evaporated in destructor-fired boilers, the average steam pressure, the weight of clinker and dust produced, the temperature in the combustion chamber and settings, and the percentage of carbon-dioxide in the flue gases. In order to determine the all-round efficiency of an installation, the leading facts to be ascertained from these data are : the weight of refuse burnt per square foot of grate area, the water evaporation per I lb. of refuse consumed from and at 212°, the average temper ature of the combustion chamber, the average carbon-dioxide gas analysis, the percentage of steam required to operate the de structor and its accessory plant, and the percentage and quality of clinker compared with the weight of refuse consumed.Temperatures in the combustion chamber may be obtained by the use of the Fery radiation pyrometer, after the boiler by a mercury pressure pyrometer, and other temperatures by the mercury expansion thermometer. Other instruments used in con nection with destructor tests are the Meyland-D'Arsonval gal vanometer, and the Chatellier resistance pyrometer and galvano meter, as made by the Cambridge Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd. The continuous record of the chemical composition of the gases in the combustion chamber may be taken by means of the Sim mance and Abady recorder.

The higher the percentage of carbon-dioxide passing away in the gases the more efficient the furnace, provided there is no formation of carbon-monoxide the presence of which would in dicate incomplete combustion. The theoretical maximum of car bon-dioxide for refuse burning is about 20%, and, by maintaining an even clean fire, by admitting secondary air over the fire, and by regulating the dampers or the air-pressure in the ashpit, an amount approximating to this percentage may be attained in a well designed furnace if properly worked. If the proportion of free oxygen (i.e., excess of air) is large, more air is passed through the furnace than is required for complete combustion, and the heating of this excess is clearly a waste of heat.

Capital Costs and Working Expenses.

The capital cost of a destructor installation will depend very largely upon the local conditions, situation and nature of the site. In addition to the customary destructor buildings, cells, charging and clinkering machinery, brick settings, chimney shaft, inclined approach road way, water supply, drainage, light, etc., a modern installation also usually comprises screening machinery for the removal of dust up to about fin. to din. gauge, power-driven elevators, sorting conveyor, electro-magnetic separators, clinker crusher and grading machinery, mortar mills, tin baling press, mess room and spray room, foreman's cottage, office, workshop, weigh-bridge, necessary road and yard formation, electric lighting and other accessories. The writer has had recent occasion closely to investigate the capital cost of such an installation for erection in Kent, capable of dealing with about 72 tons of refuse per 24 hours, and the inclusive cost, based on quotations received, was estimated at £19,700 including a i 5oh.p. Lancashire boiler, a 4ob.h.p. horizontal engine, and a five-kilowatt electric lighting set, all comprised within destructor buildings built with steel stanchions, i4in. piers and gin. plain brick panels.As regards the working expenses of dealing with the refuse by destructor, the average cost per ton of refuse, based on data from 20 towns in the south of England, was found to be 7s 4-id. exclusive of loan charges. On a large portion of this class of plant the depreciation and wear and tear are considerable. The loan period would therefore be relatively short, say from ten to 15 years only. Loan charges may amount to about 4s. per ton, under present conditions of high costs of building and machinery, on a complete scheme as outlined above. In view of the high temperature at which the cells work they would probably require relining within a period of ten years.

As regards labour required, stokers, with hand-fed plants, may deal with from five to six tons of refuse per man per eight-hour shift. For burning So tons of refuse per day of 16 hours four men per eight-hour shift would be required for stoking and firing. Extra labour would be needed for outside work such as clinker crushing, mortar making and other such work.

General Arrangement of Station.

In the general arrange ment of a destructor station the cells are placed either side by side, with a common main flue in the rear, or back to back with the main flue arranged in the centre and leading to a tall chimney-shaft. The heated gases on leaving the cells pass through the combustion chamber into the main flue, and thence go forward to the boilers, where their heat is absorbed and utilized. Forced draught, or in many cases, hot blast, is supplied from fans through a conduit commanding the whole of the cells. An inclined road way, of as easy gradient as circumstances will admit, is provided for the conveyance of the refuse to the tipping platform, from which it is fed, either by hand or mechanically, through feed-holes into the furnaces. In the installation of a destructor, the choice of suitable plant and the general design of the works must be largely dependent upon local requirements, and should be en trusted to an engineer experienced in these matters. The following primary considerations, however, may be enumerated as ma terially affecting the design of such works: (a) The plant must be simple, easily worked without stoppages, and without mechanical complications upon which stokers may lay the blame for bad results; (b) it must be strong, must withstand variations of tern perature, must not be liable to get out of order, and should admit of being readily repaired; (c) it must be such as can be easily understood by stokers or firemen of average intelligence, so that the continuous working of the plant may not be disorganized by change of workmen; (d) a sufficiently high temperature must be attained in the cells to reduce the refuse to an entirely innocuous clinker, and all fumes or gases should pass either through an adjoining red-hot cell or through a chamber whose temperature is maintained by the ordinary working of the destructor itself at a degree sufficient to exclude the possibility of the escape of any unconsumed gases, vapours or particles. The temperature may vary between i,800° and Modern practice favours the continuous hearth principle where by the furnace gases pass from one cell to another on their way to a common combustion chamber; (e) the plant must be so worked that while some of the cells are being recharged, others are at a glowing red heat, in order that a high temperature may be uni formly maintained ; (f) the design of the furnaces must admit of clinkering and recharging being easily and quickly performed, the furnace doors being open for a minimum of time so as to obviate the inrush of cold air to lower the temperature in the main flues, etc. ; (g) the chimney draught must be assisted with forced draught from fans or steam jet to a pressure of i 2in. to gin. under grates by water-gauge; (h) where a destructor is required to work without risk of nuisance to the neighbouring inhabitants, its effi ciency as a refuse destructor plant must be primarily kept in view in designing the works, steam-raising being regarded as a sec ondary consideration; (i) where steam-power and a high fuel efficiency are desired a large percentage of carbon-dioxide should be sought in the furnaces with as little excess of air as possible, and the flue gases should be utilized in heating the air-supply to the grates, and the feed-water to the boilers ; (j) ample boiler capacity and hot-water storage feed-tanks should be included in the design where steam-power is required.

. Clinker Asphalt Plants.

The cells at the Brighton destruc tor works have been reconstructed by Messrs. Heenan and Froude, Ltd., of Worcester, and a modern clinker asphalt plant installed. By means of this the destructor clinker is crushed, graded and mixed for use as an asphalt carpet or surfacing for roadways. This plant is illustrated in figs. 3 and 4. Where there is a suitable outlet for the manufactured product, such a plant is found to be a serv iceable addition to a destructor installation, and affords a satis factory means of using large quantities of clinker. The equip ment consists of two sections—a crushing, separating, screening, grading and storage section, and a drying, heating and mixing section for the manufacture of asphalt from the prepared clinker., The amount of clinker produced in Great Britain ranges from 2o% to about 35% and it is important, financially, that suitable outlets should be made available for its use. In addition to asphalt making, it may be used in making clinker bituminous grout for carriageways, for tarmacadam work, for making concrete building blocks by hand-operated machines or by hydraulic plants. Paving slabs, kerbs and channels may also be made from the crushed and graded clinker. Other uses include the bedding of street paving with the crushed material, the making of mortar for building, and the bottoming of roads and footways.

The carbon content of the clinker is an indication of the effi ciency of the combustion in the cell, and should always be low. The usual accessories for dealing with clinker include crushing, elevating and grading machinery, paving slab presses and ma chinery, clinker concrete block and brick making machines, mortar mills and asphalt plant. At the Coventry destructor the clinker represents about 25% of the refuse, and some 5,000 tons of clinker per annum are utilized for slab making, mortar making, tar macadam work, for road foundations and similar requirements.

Use of Surplus Heat.

In order to render the refuse and gases therefrom perfectly innocuous and harmless, the modern high temperature destructor must be worked at a temperature of not less than from 1,80o° to 2,000°. The great heat thus developed has naturally suggested its utilization for steam production, and, where suitable outlets exist for its use, a reasonable additional expenditure on plant and labour is justified. The actual calorific value of refuse varies widely in different places and also during different seasons of the year, but as a general average, with a suitably designed and well managed plant, an evaporation of lb. of water per lb. of refuse burned is a result readily attainable, and one which affords a basis of calculation which engineers may adopt in practice. The evaporative results obtained depend also upon the industry and skill of the stokers as well as on the quality of the refuse. Many destructor steam-raising plants give con siderably higher results than those named above, and evaporations approaching 2 lb. of water per lb. of refuse are met with under favourable conditions. In the coal-mining districts of Rhondda and Pontypridd evaporations from and at 212° of 4.15 lb. and 3.47 lb. of water per lb. of refuse are recorded. From long ex perience it may be accepted, therefore, that the calorific value of unscreened house-refuse varies from to 2 lb. of water evaporated per lb. of refuse burned, and, taking the evaporative power of coal at io lb. of water per lb. of coal, this gives for domestic house-refuse a value of from one-tenth to one-fifth that of coal under normal conditions.

Destructor Electric Combinations.

In practice, however, when the electric energy is for the purpose of lighting only, diffi culty has been experienced in fully using the thermal energy from a destructor plant owing to the want of adequate means of storage either of the thermal or of the electric energy. A destructor usually produces a fairly uniform amount of heat throughout the period of its work, while the consumption of electric lighting current is irregular and the maximum demand may be several times the mean demand. This difficulty may be greatly reduced by the provision of ample boiler capacity, or by the introduction of feed thermal storage vessels in which hot feed-water may be stored during the hours of light load. At the time of maximum load the steam boiler may be filled directly from these vessels which work at the same pressure and temperature as the boiler.In cases where there is a day load, as for electric motive power purposes, equalizing the demand on both the destructor and the electric plant, the situation becomes much more favourable to the full utilization of the available surplus heat.

As regards sewage pumping, destructor installations of the New Destructor Co. are supplying power for this purpose at Gosport, Hampton, Leamington, Teddington, Worthing and other places, and a similar service is rendered by plants of Messrs. Manlove, Alliott and Co. at Guildford, Stroud and Cambridge, whilst the Heenan destructor affords power for sewage pumping at Ports mouth, Nuneaton, Hanwell, Lincoln and elsewhere. (See REFUSE DISPOSAL for American practice.) BIBLIOGRAPHY.-W. H. Maxwell, Removal and Disposal of Town Bibliography.-W. H. Maxwell, Removal and Disposal of Town Refuse, with an exhaustive treatment of Refuse Destructor Plants; a special supplement embodies later results; H. F. Goodrich, Refuse Disposal and Power. See also the Proceedings of the Incorporated Association of Municipal and County Engineers, vols. p. 216, xxii. p. 211, XXiV. p. 214 and xxv. p. 138; the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, vols. cxxii. p. 443, cxxiv. p. 469, cxxxi. P. 413, cxxxviii. p. sos, cxxix. p. 434, cxxx. pp. 213 and 347, cxxiii. PP. 369 and 498, cxxviii. p. 293, cxxxv. p. 30o, and cxxxix.

(W. H. M.)