Diphtheria

DIPHTHERIA, an acute infectious disease, accompanied by a membranous exudation on a mucous surface, generally the tonsils and back of the throat or pharynx.

As a rule, early symptoms are comparatively slight, viz., chilliness and depression. A slight feeling of uneasiness in the throat is experienced along with some stiffness of the back of the neck. The throat is reddened and somewhat swollen, par ticularly in the neighbourhood of the tonsils, the soft palate and upper part of pharynx, and there is tenderness and swelling of the glands at the angles of the jaws. The affection of the throat spreads rapidly, and soon the characteristic exudation appears on the inflamed surface as greyish-white specks or patches, increasing in extent and thickness until, in a well de veloped case, a yellowish-looking false membrane is formed, firmly adherent to the mucous membrane and if removed soon repro duced upon the raw, bleeding, ulcerated surface so left. It may cover the whole of the back of the throat, and the posterior nares, and spread downwards into the air-passages. Portions may be detached spontaneously, and expelled by coughing. There is pain and difficulty in swallowing, but unless the disease has affected the larynx no affection of the breathing. The voice acquires a snuffling character. When the disease invades the posterior nares an acrid, foetid discharge, and sometimes also copious bleeding, takes place from the nostrils. Along with these local phenomena there is in cases severe constitutional dis turbance. While there may be no great amount of fever, there is marked depression and loss of strength. The pulse becomes small and frequent, the countenance pale, the swelling of the glands of the neck increases, and albumen appears in the urine. Unless favourable symptoms emerge death takes place within three or four days or sooner, either from the rapid ex tension of the false membrane into the air-passage, giving rise to asphyxia, or from a condition of general collapse, which is sometimes remarkably sudden. In cases of recovery the change for the better is marked by an arrest in the extension of the false membrane, the detachment and expectoration of that already formed, and the healing of the ulcerated mucous membrane beneath. Recovery, however, is slow, and it is many weeks before full convalescence is established. Even, however, where diphtheria ends favourably, a few weeks later paralysis of the sof t palate and pharynx may occur, causing difficulty in swallowing and regurgitation of food through the nose, and giving a peculiar nasal character to the voice. Other forms of paralysis occurring after diphtheria are those affecting the muscles of the eye, which produce a loss of the power of accommodation and consequent impairment of vision, paralysis of both legs, and occasionally also of one side of the body (hemiplegia). These symptoms, after continuing for a variable length of time, almost always ultimately disappear.

Causation.

The exciting cause of diphtheria is a micro-organ ism, identified by Klebs and Loftier in 1883 (see BACTERIA AND DISEASE). It has been shown by experiment that the symptoms of diphtheria, including the after-effects, are produced by a toxin derived from the micro-organisms which lodge in the air-passages and multiply in a susceptible subject (see IMMUNITY). Cats and cows are susceptible to the diphtheritic bacillus, but actual cases among them are very rare; and f owls, turkeys and other birds have been known to suffer from a diphtheria-like disease, not due however, to the diphtheria bacillus; other domestic ani mals appear to be more or less resistant or immune. Children are far more susceptible than adults, but even children may have the Klebs-Loffier bacillus in their throats without showing any symp toms of illness, though such children are "carriers" (q.v.). Alto gether there are many obscure points about this micro-organism, which is apt to assume a puzzling variety of forms.Prevalence.—Diphtheria is endemic in all European and American countries, and the incidence varies greatly in different countries and, from year to year, even in the same country. In other words, diphtheria, though always endemic, exhibits at times a great increase of activity, and becomes epidemic or even pandemic.

Dissemination.

The contagion is spread by means which are in constant operation, whether the general amount of disease is great or small. Water, so important in some epidemic diseases, is believed not to be one of them. On the other hand, outbreaks of an almost explosive character, besides minor extensions of disease from one place to another have been traced to milk; but several cases have been ascribed to infection from cows with a diphtheritic affection of the udder. Hunian intercourse is the most important means of dissemination, the contagion passing either by actual contact, as in kissing, or by the use of the same utensils and articles, or by mere proximity. In the last case the germs must be supposed to be air-borne for short dis tances, and to enter with the breath. In the act of talking, tiny infected droplets are expelled into the air. It has been held that diphtheria is a rural rather than an urban disease, but this view is negatived when sufficiently numerous data over a long period of years are analysed. Diphtheria appears to creep about very slowly, as rule, from place to place, and from one part of a large town to another; it forsakes one district and appears in another; occasionally it attacks a fresh locality with great energy, presumably because of the susceptibility of the inhabitants. who are, so to speak, virgin ground. But through it all personal infection is the chief means of spread.The acceptance of this doctrine has directed great attention to the practical question of school influence. There is no doubt whatever that it plays a very considerable part in spreading diphtheria. The incidence of the disease is chiefly on children, and nothing furnishes such constant and extensive opportunities for personal infection as school attendance. Many outbreaks have definitely been traced to schools. From a practical point of view the problem is a difficult one, but has been simplified by discovery of the Schick reaction and the prophylactic anti toxin treatment of those exposed to infection in whom the re action is positive (see MEDICAL RESEARCH). All these consider ations imply the necessity of segregating the sick in isolation hospitals. Of late years this preventive measure has been carried out with increasing efficiency, but, unfortunately, the complete segregation of infected persons is hardly possible, because of the mild symptoms, and even absence of symptoms, exhibited by some individuals. A further difficulty arises with reference to the discharge of patients. It has been proved that the bacillus may persist almost indefinitely in the air-passages in certain cases, and in a considerable proportion it does persist for several weeks after convalescence. On returning home such cases may, and often do, infect others. The method usually adopted is to retain the patient until the throat has been found free from B. diphtheria on each of three consecutive weekly bacteriological tests. These tests are generally started I 2 days of ter the onset of the disease and made every two days. This still leaves the prob lem of dealing with persistent carriers unsolved.

Treatment.

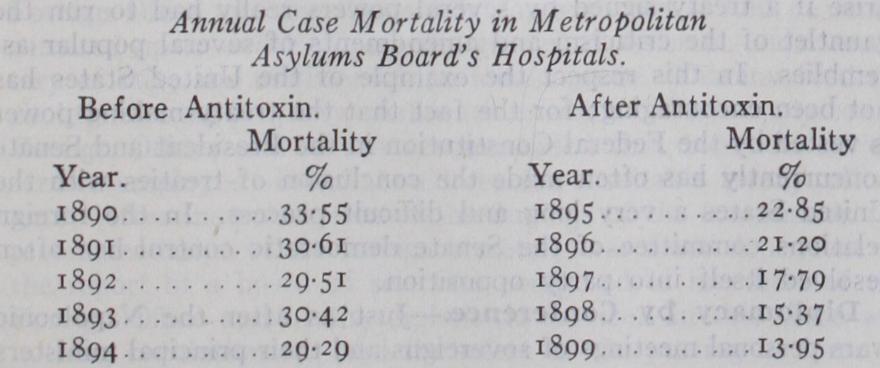

Since the antitoxin treatment was introduced in 1894 it has overshadowed all other methods. owe this drug originally to the Berlin school of bacteriologists, and particularly to Dr. Behring. (See BACTERIA AND DISEASE; IMMUNITY; SERUM THERAPY.) Since then an enormous mass of facts has accumulated from all quarters of the globe, all testifying to the value of antitoxin in the treatment of diphtheria. The experience of the hospitals of the London Metropolitan Asylums Board for five years before and after antitoxin may be given as a particularly instructive illustration ; and the subsequent reduction in the rate of mortality (12% in 1900, 11•3 in 1901, 10.8 in 1902, 9.3 in 1903, and an average of 9 in 1904-8) added further confirmation. Since then a further reduction has taken place. During 1923-26 the case mortality (annual reports of the chief medical officer of the Ministry of Health) was: 1923, 5.95; 5•81; 1926, 5.86.

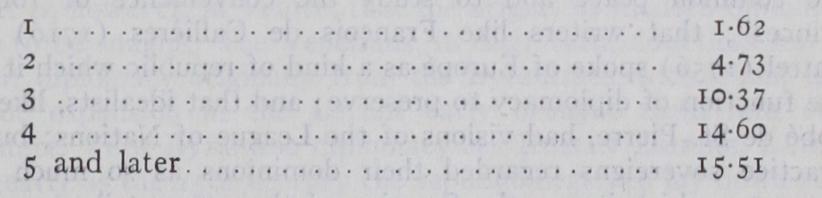

The number of cases dealt with in these five antitoxin years was 32,835, or an average of 6,567 a year, and the broad result is the reduction of mortality by about one-half. It is a fair infer ence that the treatment saved the lives of about i,000 children each year in London alone. This refers to all cases. Those which occur in the hospitals as a sequel to scarlet fever, and consequently come under treatment from the commencement, show very much more striking results. The case mortality, which was 46.8% in 1892 and 58.8% in 1893, has been reduced to 3.6% since the introduction of antitoxin. This is a special example of the gen eral law that the efficacy of antitoxin treatment varies inversely as the length of time that the disease has existed prior to ad ministration of antitoxin. The following table (compiled from the annual reports of the Metropolitan Asylums Board), gives the case mortality of diphtheria on this basis:— Day of disease on which Case mortality antitoxin treatment was begun. % But the evidence is not from statistics alone. The beneficial effect of the treatment is equally attested by clinical observation. Adult patients have described the relief afforded by inoculation ; it acts like a charm, and lifts the deadly feeling of oppression off like a cloud in the course of a few hours. Finally, the counter acting effect of antitoxin in preventing the disintegrating action of the diphtheritic toxin on the nervous tissues has been demon strated pathologically. It has been said that diphtheritic paralyses are commoner since the introduction of antitoxin, but obviously the modern greater survival of diphtheria patients implies the existence of persons in whom these paralyses can be observed, who, formerly, would have died too early to manifest them.