Distribution of Animals

DISTRIBUTION OF ANIMALS. A solution of the prob lems of zoogeography, which attempts to explain the distribution of animals on the earth, may be sought in two directions. We may investigate the distribution of related groups of animals in the separate regions of sea and land, and from this seek to draw conclusions as to former connections between the present habitats of related forms, the historical aspect (see ZOOLOGICAL DISTRIBU TION ), or we may inquire what animal forms dwell together in places showing certain conditions of environment, and by what char acters they are adapted to existence under these conditions, the oecological aspect, which is considered here.

For animal life to succeed at all, certain general conditions must be fulfilled; if but one is lacking, animal life also is absent. One or these primary conditions is water. In places such as extremely arid deserts, where water-supply and dewfall fail com pletely for long periods, no animal can live.

To many animals light is not immediately necessary. In sub terranean caverns, and in the great depths of the ocean (1,7oom. ), light is absent, yet animals live in these places pro vided they can find food. Light is indispensable, however, to green plants since it supplies the energy for the manufacture of organic substances. Animals are dependent on organic food, and so ultimately, upon plants. Light, therefore, is indirectly necessary to animals.

All life is confined within certain limits of temperature. Al bumin, the chief constituent of protoplasm, coagulates at about 7o° C. Protoplasm, too, cannot live if its fluid content is frozen, i.e., at temperatures below about —5° C. Thus animal life is absent in the hottest springs. (some lower animals, such as Protozoa, rotifers, snails, can live in hot springs of 45°-50° C) ; while no animals are present in the perpetual snows of mountains.

Food is absolutely essential to all animals. In addition to or ganic materials (albumin, carbohydrates, fats), oxygen is needed, to combine with the products of the breaking-down of organic food, and thus liberate energy. There are some places where oxygen and therefore animal life is absent ; in the depths of some parts of the ocean and in volcanic places where carbon dioxide (COS) escapes from the ground, e.g., the floor of the Grotto del Cane at Pozzuoli, near Naples.

The quantity of moisture, warmth and oxygen, required by an animal varies in different species; some are able to manage with little, others need much, while others again are indifferent to the amount. Animals requiring amounts of moisture, warmth or oxy gen (whether great or small) not varying beyond narrow limits are termed stenohygrous, stenothermic or stenoxybiont, respectively; those having wide limits, euryhygrous, eurythermic or euroxy biont ; animals in all respects indifferent are euryoekous, those requiring definite quantities stenoekous. Euryoekous animals gen erally have a wider distribution than stenoekous.

The different regions of the earth occupied by living beings, the sea, fresh water and dry land, are fundamentally different in the conditions they offer and in the demands they make.

Sea.

The sea is the home of life. In it are represented all the structural types in which animal life manifests itself. Echino derms, Tunicates, Cephalopoda, many groups of worms, Radio laria and Foraminifera are confined to the sea. Myriapoda and Amphibia only are not represented there. Salt water of the con centration of sea-water is the true medium for protoplasm. Sea water has the same osmotic pressure as the fluid in protoplasm. For that reason it withdraws no materials from the protoplasm, neither does it give up any to it. If human blood is examined in salt solutions of strengths such as 0. 2 %, 0.75% and I the fate of the red corpuscles differs greatly in each case (fig. I. A—C.). In 0.75% NaCl they remain unchanged; this solution is isotonic with the fluid they contain. In 0.2 % NaCl the corpuscles give up colouring matter to the salt solution, swell and ultimately burst (a). In 1% NaCl they shrivel (c), water having been withdrawn from them. Animals living in the sea are situated similarly to the corpuscles in the 0.75% salt solution; they need not isolate their inner medium from the environment.In the sea, too, the conditions of life undergo least change. All seas communicate with one another, and their waters are con tinually mingled. The salinity, therefore, is about the same in all regions, the temperatures are similar, and vary much less than in fresh water, or in the atmosphere. The amount of oxygen present is very constant. Exceptions are secondary seas having only a narrow connection with the ocean, such as the Mediter ranean and Baltic.

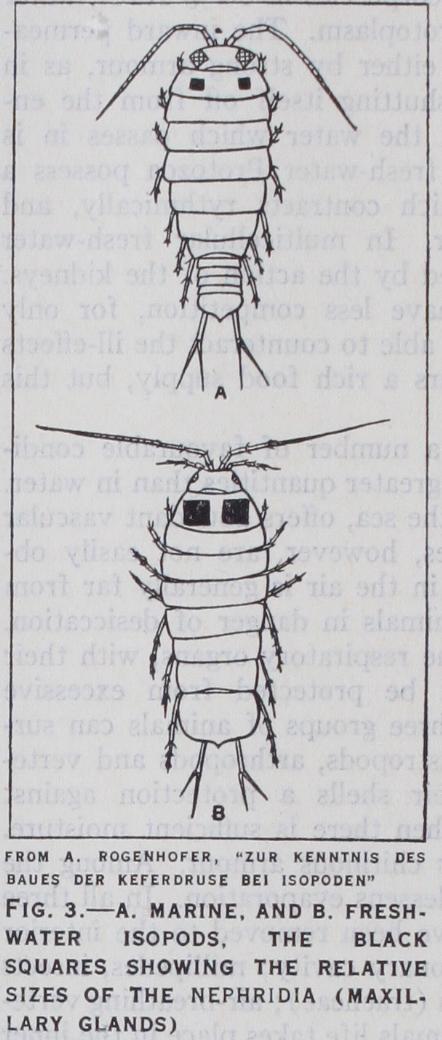

Fresh Water.—Fresh water, on the contrary, is dangerous to living organisms on account of the small amount of salts con tained in solution. As in the red corpuscles in o. 2 % NaC1, water is continually passing into the protoplasm. The inward permea tion of water may be prevented either by strong armour, as in water insects, the animal body shutting itself off from the en vironment; or, more frequently, the water which passes in is constantly discharged. Thus all fresh-water Protozoa possess a contractile vacuole (fig. 2), which contracts rythmically, and discharges water to the exterior. In multicellular fresh-water animals the same result is reached by the action of the kidneys. Fresh-water animals, however, have less competition, for only relatively few marine animals are able to counteract the ill-effects of fresh water. Fresh water offers a rich food supply, but this must be earned.

Land.—Terrestrial life offers a number of favourable condi tions. Oxygen is present in much greater quantities than in water. Further, dry land, in contrast to the sea, offers abundant vascular plants as food. These advantages, however, are not easily ob tained. The amount of moisture in the air is generally far from saturation point, and puts the animals in danger of desiccation. The outer skin, and, above all, the respiratory organs, with their large, permeable surfaces, must be protected from excessive evaporation. Only members of three groups of animals can sur vive life in a dry atmosphere, gastropods, arthropods and verte brates. Gastropods have in their shells a protection against desiccation ; they emerge only when there is sufficient moisture. Terrestrial arthropods have their chitinous armour. Among the vertebrates, the horny epidermis lessens evaporation. In all three groups the respiratory organs have been removed to the interior of the body. Snails have a pulmonary cavity; millipedes, insects and spiders have internal air-tubes (tracheae) ; air-breathing verte brates have lungs. In all these animals life takes place in the inner albuminous salt solution, not in the atmosphere.

The air also offers a new condition in its lesser density. Water supports the animal body, leaving little work for muscles and sup porting organs. In the air, on the contrary, the body must be supported and compact to retain its form. All terrestrial animals, therefore, have skeletons ; snails their shells, arthropods their chitinous armour and vertebrates their bony skeletons. Further, water supports, or retards the sinking of, much floating matter, such as small plants or animals, and the disintegration products of organisms (detritus), and this is carried as food to the animal population. For this reason, fixed animals may be present in water in great numbers. In terrestrial life, animals must search for their food, and fixed forms, except some parasites (e.g., cochineal insects), do not occur.

Most terrestrial plants cannot be utilized by animals without undergoing further processes because the albumin, fat and starch are all enclosed in a cellulose envelope. Animals, except some snails (e.g., Helix pomatia), possess no ferment in their gastric juice which will dissolve this substance. The cellulose membrane must therefore be broken up to liberate the food. Thus snails tear the cells to small pieces by their radulae ; arthropods fragment vegetable food with their jaws ; mammals chew with their teeth ; and birds grind up food in their gizzards. The numerous herbi vores render possible the existence of carnivores; many insects, almost all amphibians and reptiles, and many birds and mammals are insectivorous or predatory.

One particular difficulty to which terrestrial animals are gener ally exposed is the great variations of temperature. In the sea, the temperature of the water over large areas is subjected only to slight and gradual variations. The daily variations are also slight. In fresh water the temperature does not sink below zero; in deep water it is unusual for it to sink below 4° C. Only in summer, in the smallest basins, does it reach 25°-30° C. On land also there are regions with only slight diurnal and seasonal tem perature variations, e.g., tropical forests. The difference between diurnal and nocturnal temperatures, however, is usually consider able. The difference between the extreme temperatures of differ ent seasons at certain places is very large. In Central Europe it amounts to 9o° F, in Werchojansk (Eastern Siberia) it even reaches 18o° F. During the winter, life in the sea and in fresh water goes on unchecked, al though isolated species hibernate. On land, in the temperate and frigid zones, all life becomes tor pid under the influence of winter cold; even the nightly cooling of the air makes many animals slug gish. The organization of ter restrial animals is profoundly in fluenced by variations of tem perature ; muscles become stiff, glandular activity ceases. If, however, an animal can produce inside itself by metabolic pro cesses a favourable temperature, and can maintain this through nervous control, it is freed from these temperature variations. Such animals are termed homoio thermal (warm-blooded animals). Homoiothermal animals have, nevertheless, to pay a price for this advantage; they become slaves to their increased food-requirements. Poikilothermal (cold blooded) animals can fast for long periods ; a snake or frog can go without food for six months, and aestivating snails for four or five years. Homoiothermal animals, on the contrary, quickly succumb to lack of food.

The Conditions of Dispersal.—In the various regions in habited by living organisms, the sea, fresh water, and dry land, animal dispersal is influenced in different ways, and the barriers opposed to it differ. The seas are in communication with one an other in all parts of the earth ; though the present connections be tween the Indo-Pacific and the Atlantic are in polar and sub-polar regions and, on that account, are impassable for warm-stenother mal animals. For most marine animals, however, dispersal depends on their powers of migration. Sedentary animals can extend their range only during the short, free-living, larval life, but powerful swimmers like sharks and mackerel are found in all warm seas. Isolation, however, is an important factor in transformation of species. The great variety of marine animals is therefore astonish ing, when we consider the similarity of conditions of life in the various seas.

In inland waters conditions are quite different. This region is di vided into innumerable small sections, such as streams, rivers, lakes and ponds separated by insurmountable obstacles in seas and land. Standing waters in particular are very varied in the materials they hold in solution, in conditions of light and temperature, in the fertilizing matter they receive, and therefore in their plant life. This wide-spread isolation under the influence of environment might give rise to the development of numerous different species, and to great variability within the limits of each species, but actually the fauna of fresh water is very rich in cosmopolitan genera and species, and, over the whole earth, shows great simi larity. The origin of this is the transitory nature of fresh waters. Even in historic times, rivers have changed their courses, dwindled and dried up. Small standing waters are also apt to dry up. Lakes gradually become filled up. The existence of enclosed basins is not of sufficient duration for a thorough transformation of the species dwelling in them. Newly-arisen waters become populated from those already in existence by organisms which can either fly from one basin to the other, or be carried as spores by winds or water-birds. It is only in deep, and therefore ancient, basins that a characteristic fauna has been able to develop, as in Lake Baikal (I,373m. deep), and Lake Tanganyika (59om.).

Dry land is divided into many small, more or less isolated, sections by seas, mountains, deserts and rivers. But terrestrial animals have very variously developed organs of locomotion, and therefore the effect of isolation varies. The great environmental differences have a similarly isolating effect. The transformation of species is thus exceedingly vigorous on dry land, but is con fined to those animals able to live there (gastropod molluscs, arthropods and vertebrates). The sea is a much more extensive arena for living organisms. Nevertheless, t of all animal species are terrestrial. We are acquainted with about 3,000 living species of Coelenterata and Echinoderma, animals confined to the sea ; on the other hand, 400,000 species of insects have been described. But the range of variation among echinoderms and coelenterates is much greater than in the insects.

Prolonged isolation gives a striking character to the animal life of a district. The variety of the fauna in the different biotopes arises through transformation of the stock originally present. For that reason the interrelationship of the members of the fauna is much greater than in districts where continual intermix ture is possible with forms which wander in from the surrounding regions. Such differentiation is found in the Caspian sea, in Lake Baikal, in Madagascar and in South America. In Lake Baikal 79 species of fresh-water Tricladida (Turbellaria) are found, more than half the known species. A third of all the fresh-water fishes in South America belong to the family Characinidae, and include mud- and plant-eating, and even carnivorous forms. Among mammals, the numerous adaptations shown by rodents of the family Hystricomorpha is most remarkable.

Area of

region occupied by a species is known as its area of distribution. The size of the area varies in the different species; it depends on the presence of suitable dwell ing places, on the barriers limiting dispersal, on the powers of migration of the species and the facility with which it may be transported, on its oecological value, and on its history.Species with restricted range are termed stenotopic, those with wide range, eurytopic. Species becoming extinct, or newly-arisen, often have a restricted range ; examples of the former are the primitive lungfish, Neoceratodus (Murray river, Australia), and the lizard, Sphenodon (New Zealand) ; of the latter, the moth Cymatophora or var. albigensis in the industrial districts of Eng land and Hamburg. A closely confined habitat also hinders dis persal ; such are Lake Baikal and the Hawaiian islands, with their many endemic species. Changes in the area of a species may take place before our eyes; the jigger flea (Sarcopsylla penetrans) first arrived in Africa in 1872, and since that time has spread from the west coast to the east. The inner limit of size of an area varies with the size of the animal and the nature of its food. Carnivores require a larger range than herbivores of the same size. For this reason beasts of prey cannot exist on small islands. Cosmopolitan species are those present generally over the whole earth wherever they can find suitable dwelling places. (A cosmopolite, however, is not found in all the regions supporting life, i.e., the sea, fresh water and dry land.) As examples may be mentioned the edible mussel (Mytilus edulis), found in all the seas of the world, the brine shrimp (Artemia salina) universally present in salt marshes.

Small districts are generally poor in species, large districts having the same conditions are richer. Thus the number of species of fishes decreases in proportion to the size of the river plus its tributaries :— Biotope and district showing uniformity in environmental conditions is uniform also in animal population; it is called a biotope (habitat). A small birch wood, a cavern or a rocky coast is a biotope. A biotope may often be subdivided into areas having particular conditions, and, therefore, a particular kind of fauna ; e.g., a pool in a cavern. These are termed facies. Similar biotopes are included in larger units termed biochores; the biotope "green forest" is included in the biochore "forest." Biochores are grouped in larger units, termed biocycles. These are sea, fresh water and dry land. These divisions are independent of the zoological distributions, which have to do with the sys tematic relationship of the animal population.

The animal population of a biotope is not a haphazard collec tion ; the members are in close association one with another, and, together with the plant life, form a unit of a distinctive kind, an association of forms of life, or biocoenosis. To the biocoeno sis belong all organisms, plant or animal, present in the biotope. They influence one another mu tually, and are in many ways de pendent on each other. Producers (chiefly plants), and consumers (animals), dwell beside one an other, but the products of animal metabolism are food for the plants, and animals are often nec essary for the fertilization of flowering plants. Among the ani mals themselves there are bonds, such as hunter and prey, host and parasite ; they may live in symbiosis or compete as rivals. Should one kind of organism be come eliminated, or get the upper hand, many members are af fected, favourably, or otherwise —the balance of the biocoenosis is disturbed.

Every biotope has a population of characteristic constitution. Not all members of a biocoeno sis are characterized in similar ways, or confined to one partic ular biotope. There are animals present only in certain biotopes, e.g., the brine shrimp (Artemia), in salt inland waters; they are the predominant forms in this biotope, and in its biocoenosis, and are termed eucoenic. Animals always present in a biotope, but also constantly found in other localities, are termed tychocoenic; thus, the wolf and eagle are found on the steppes, but are also characteristic of mountainous and forest regions. Xenocoenic animals are chance members of the biocoenosis, into which they may have been forced from the surrounding district, or through which they may be passing.

The inhabitants of the same biotope are subject to the same en vironmental conditions, and must be in harmony with them. Thus they may resemble one another in certain respects without being related. Necessity brings about quite definite adaptations through selection. The stricter the selection, the more marked are the common characteristics. Organisms dwelling in the moss on rocks, trees or walls, are often completely dried up by the sun; they can all endure desiccation and almost entirely discontinue their vital functions without suffering injury.