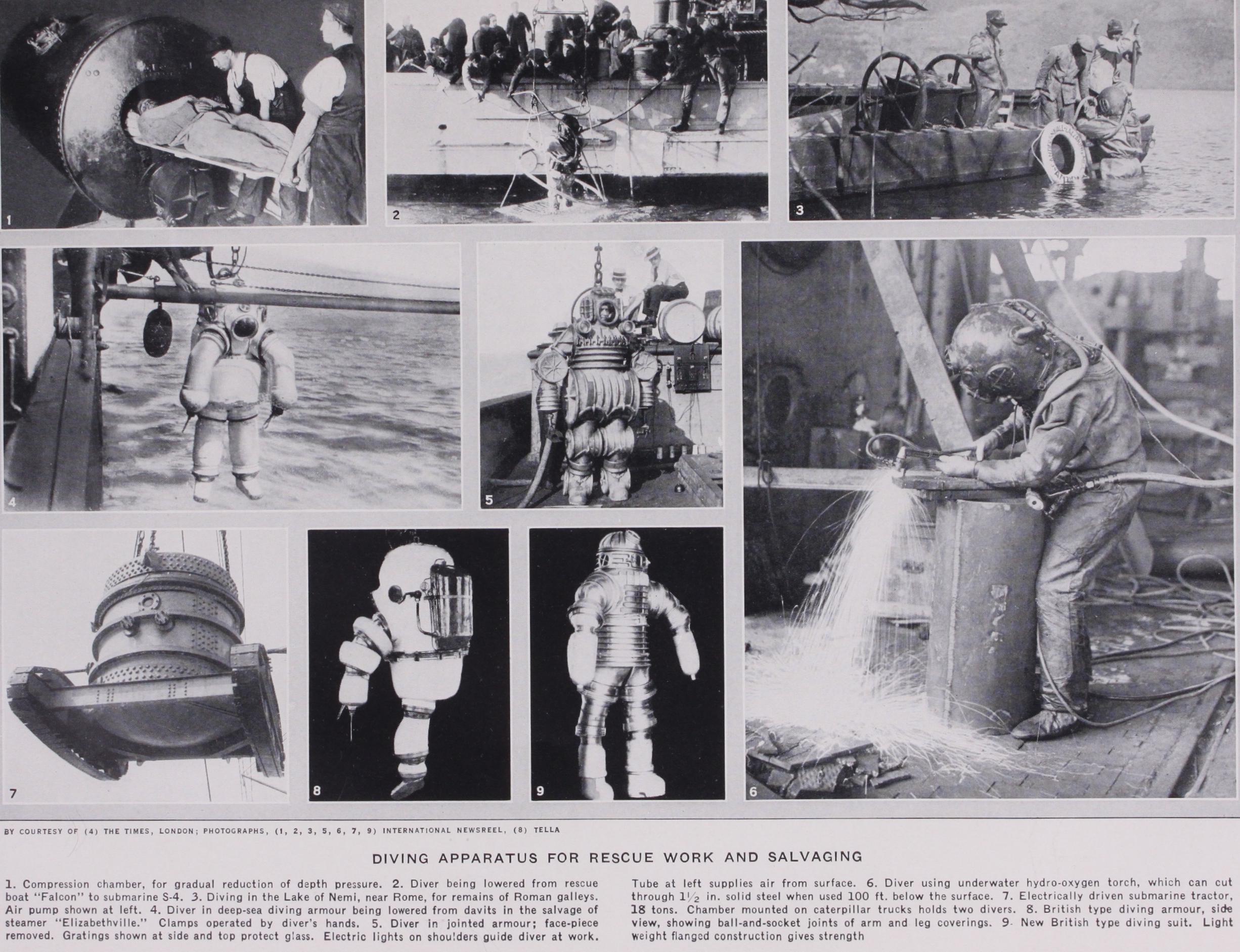

Divers and Diving Apparatus

DIVERS AND DIVING APPARATUS. The earliest reference to the practice of diving occurs in the Iliad, 16, where Patroclus compares the fall of Hector's charioteer to the action of a diver diving for oysters. Thucydides mentions the employment of divers during the siege of Syracuse to saw down the barriers which had been constructed below the surface of the water with the object of obstructing and damaging any Grecian war vessels which might attempt to enter the harbour. At the siege of Tyre, divers were ordered by Alexander the Great to im pede or destroy the submarine defences of the besieged as they were erected. Livy records that in the reign of Perseus consider able treasure was recovered by divers from the sea. By a law of the Rhodians, their divers were allowed a proportion of the value recovered.

Early Diving Appliances.

The earliest mention of any ap pliance for assisting divers is by Aristotle, who says that divers were sometimes provided with instruments for drawing air from above the water and thus they were able to remain a long time under the sea (De Part. Anim. 2, 16) , and also that divers breathed by letting down a metallic vessel which did not get filled with water but re tained the air within it (Problem. 32, 5) . It is also recorded that Alexander the Great made a descent into the sea in a machine called a Colimpha, which had the power of keeping a man dry, and at the same time of admitting light. Pliny also speaks of divers engaged in the strategy of ancient warfare, who drew air through a tube, one end of which they carried in their mouths, whilst the other end was made to float on the surface of the water. Roger Bacon in 124o, too, is supposed to have invented a contrivance for enabling men to work under water; and in Vege tius's De Re Militari (editions of I 51 i and 1532, the latter in the British Mu seum) is an engraving representing a diver wearing a tight-fitting helmet to which is attached a long. leathern pipe leading to the surface where its open end is kept afloat by means of a bladder.Repton invented "water armour" in the year 1617, but when tried it was found to be useless. G. A. Borelli in the year 1679 invented an apparatus which enabled per sons to go to a certain depth. It embodied means for altering the specific gravity of the diver, but was not practical. John Lethbridge, a Devonshire man, in the year 1715 contrived "a watertight leather case for enclosing the per son." This leather case held about half a hogshead of air, and was so adapted as to give free play to arms and legs, so that the wearer could walk on the sea bottom, examine a sunken vessel and salve her cargo, returning to the surface when his supply of air was getting exhausted. It is said that Lethbridge made a considerable fortune by his invention. The next contrivance worthy of mention and most nearly resembling the modern diving dress was an apparatus invented by Kleingert, of Breslau, in 17 98. This consisted of an egg-ended metallic cylinder enveloping the head and the body to the hips. The diver was encased first of all in a leather jacket having tight-fitting arms, and in leather drawers with tight-fitting legs. To these the cylinder was fastened in such a way as to render the whole equipment airtight. The air supply was drawn through a pipe which was connected with the mouth of the diver by an ivory mouthpiece, the surface end being held above water after the manner mentioned in Vegetius, viz. by means of a floating bladder attached to it.

In 1819, Augustus Siebe invented his "open" diving dress worked in conjunction with an air force pump. The dress consist ed of a metal helmet formed with a shoulder-plate attached to a jacket of waterproof leather. The helmet was fitted with an air inlet valve to which one end of a flexible tube was attached, the other end being connected to the air pump. The air, which kept the water down below the diver's chin, found its outlet at the edge of the jacket, exactly as it does in the case of the diving bell. Ex cellent work was accomplished with this dress—work which could not have been attempted before its introduction—but it was still far from perfect. It was absolutely necessary for the diver to maintain an upright, or but very slightly stooping, position whilst under water; if he stumbled and fell, the water filled his dress, and, unless brought quickly to the surface, he was in danger of being drowned. To overcome this and other defects, Siebe carried out a great many experiments, extending over sev eral years, which culminated, in the year 183o, in the introduction of his "close" dress in combination with a helmet fitted with air inlet and regulating outlet valves. Though, of course, many great improvements have been introduced since Siebe's death, in 1872, the fact remains that his principle is in universal use to this day. The submarine work which it has been instrumental in accom plishing is incalculable.

Modern Apparatus.

A set of ordinary modern diving ap paratus consists essentially of seven parts, viz :—(a) An air pump, (b) an incompressible helmet with breastplate, or corselet, (c) a compressible, or flexible, waterproof diving dress, (d) a length of flexible non-collapsible air tube, with metal couplings joining it to pump and helmet, (e) a pair of weighted boots, (f) a pair of lead weights for breast and back, (g) a life-line. Most apparatus is fitted with a telephone, and submarine lamps are also largely used.Helmet (figs. 1, 2 and 3).—The helmet proper is separate from the corselet, and is secured to the latter by segmental neck rings which are provided on both these parts, enabling them to be connected together by one-eighth of a turn, a catch on the back of the helmet preventing any chance of unscrewing. The helmet and corselet are usually made of highly planished tinned copper, the valves and other fittings being of gun metal. The helmet is provided with a non-return air inlet valve to which the air supply pipe is attached. This valve allows air to pass from the pump to the helmet, but not in the reverse direction. A regulating air outlet valve fitted to the helmet enables the diver to control the amount of air in the dress, and hence his buoyancy. By screwing up the valve, he retains the air in the dress, and so maintains or increases his buoyancy; by unscrewing it he allows the air to escape, thus causing the dress to become deflated, with a consequent loss of buoyancy. On reaching the bottom and start ing work, the diver will adjust his valve so as to maintain him self comfortably in equilibrium, altering the adjustment only when he wishes to ascend; that is, of course, assuming, as should be the case, that air is pumped to him at a uniform rate. Thick plate glass windows are fitted to the hel met. The front window is detachable from the helmet, usually by unscrewing, though some helmets are fitted with hinged win dows similar to those used for ships' scuttles.

Dress (fig. 4).—The diving dress is a combination suit which is made of two layers of tanned twill with pure rubber between, and which envelops the whole body from foot to neck, the sleeves being fitted with vulcanized rubber cuffs which make a watertight joint round the diver's wrists. The dress is also fitted with a vul canized rubber collar, which is secured to the corselet, or breastplate, of the helmet in such a manner as to render all water tight.

Air Pipe.—The diver's air pipe is flex ible and non-collapsible. At the ends are fitted metal couplings for securing the pipe to the pump and helmet respectively.

Boots.—To maintain himself in an up right position under water, the diver wears heavily weighted boots (about 32 lb. the pair).

Weights.—Two lead weights, 4o lb. each, one on the back and one on the chest, ensure the diver's equilibrium under water.

Life-line.—The diver's life-line is for use in case of emergency, for hauling the diver to the surface, and also for making signals, the diver and his attendant having a pre-arranged code in which varying nurnbers of pulls or jerks on the life-line have definite meanings. When the telephone is provided, the telephone wires are embedded in the life-line.

Diver's Telephone (fig. O.—This most useful instrument was introduced by Siebe, Gorman & Co. and is used to-day through out the British and many other navies. Means are provided whereby the attendant at the surface can converse with No. r or with No. 2 diver, or with both together. He can also put No.

diver into communication with No. 2, himself hearing their con versation. The telephone wires are embedded in the life-line, which has metal connections at each end for attaching to helmet and battery box. The diver's telephone receiver is situated generally in the crown of the helmet, and the transmitter tween the front glass and one of the side glasses. The diver can ring a bell or buzzer at the surface by pressing with his chin a contact-piece situated side the helmet.

Submarine Electric Lamps. (fig. 6).—Very many forms of submarine lamps are available. Of these, the most widely used are those which incorporate in candescent electric bulbs, rang ing in candle-power from s,000 down to about so, the former being supplied with current from the surface, the latter being self contained with accumulator bat teries in a watertight case.

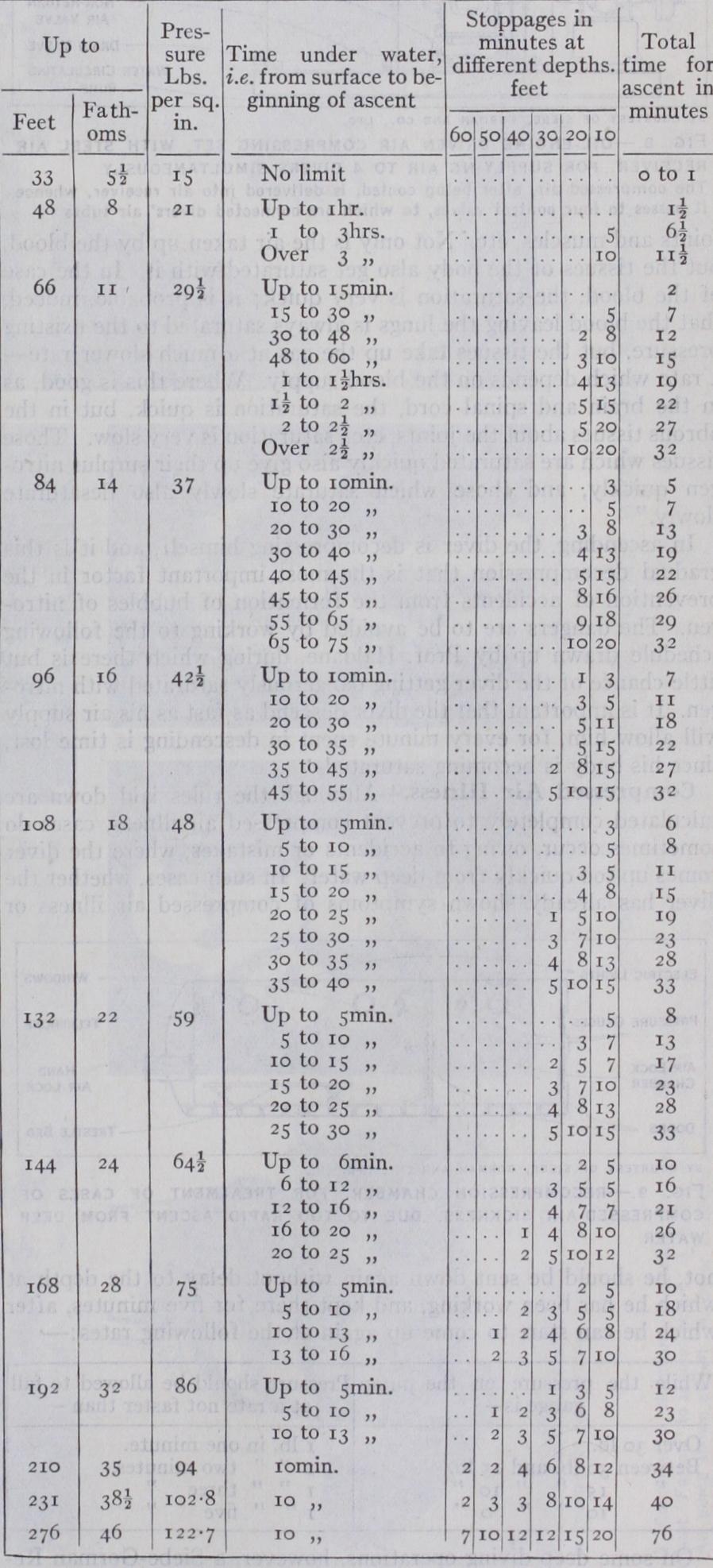

Air Pumps.—Diver's air pumps are of various patterns, depend ing principally upon the depth of water in which work is being carried out, since the greater the depth of water the greater the quantity of air required by the diver. The pumps are of the recip rocating type and are mostly manually operated. Fig. 7 shows the Siebe-Gorman two-cylinder double-acting pump (removed from its teak chest) adopted by the British Admiralty. Pressure gauges are provided which indicate the pressure of air which the pump is supplying, and the depth at which the diver is working. The cylinders are water-jacketted to ensure a supply of cool air to the diver.

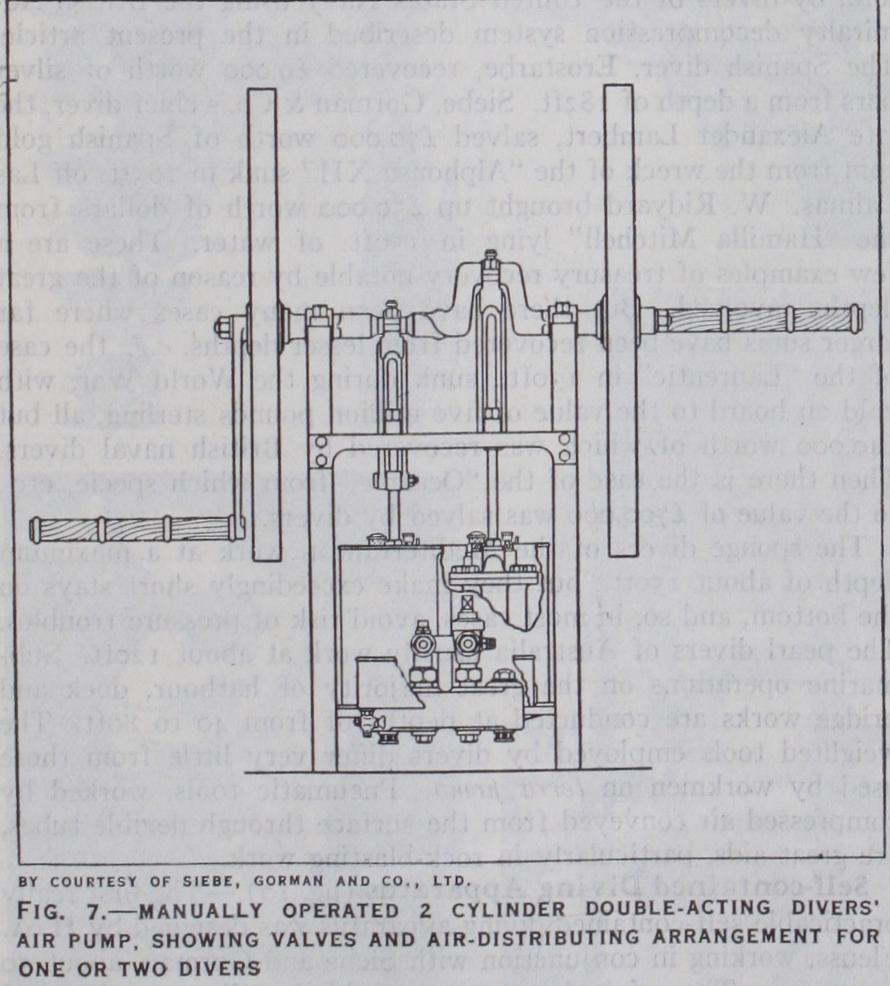

Air Compressors driven by electric motors, oil and steam en gines are sometimes employed. In these cases the air is delivered into steel reservoirs, the divers' air pipes being connected to an air control panel which receives its air from the reservoir, so that in case of a breakdown of the motive power, a reserve of air sufficient to bring the diver safely to the surface is assured.

A typical machine of this de scription is shown in fig. 8. In the pearl and sponge fisheries the small boats from which the divers work are sometimes pro pelled by oil engines which also drive the air compressors.

The type of air pumping ap paratus employed varies with the depth of water and the conditions under which the diving opera tions are conducted. Examples of manually-operated and power driven pumps are shown.

The Diver's Air Supply.

The diver's air supply must be ade quate both in volume and pressure—the volume sufficient to en sure proper ventilation of the helmet, and the pressure fully equal to that which corresponds to the depth of water at which the diver may be working. In fresh air, there is only .03% of carbon di oxide, and, at ordinary atmospheric pressure, no ill effects are felt until 3% of the gas is present. As a diver descends, the pressure is increased and the effect of a small percentage of carbon dioxide in his helmet becomes greater.

J.

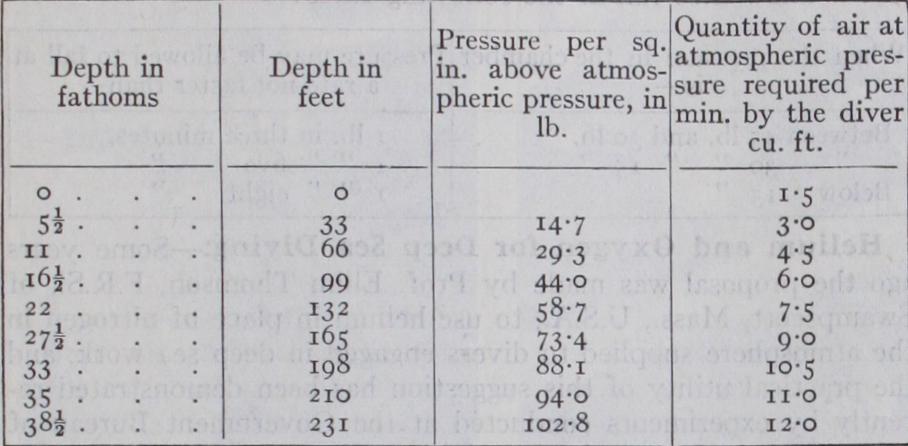

S. Haldane, who conducted deep diving experiments for the British Admiralty, found from a large number of analyses of air issuing from the diver's helmet, that i • scu. f t. of air per minute would be needed to keep the percentage of carbon dioxide at a safe level. This volume of air is required at all depths, so that the ac tual quantities required at different depths down to 231 ft. are as follows :— Effects of Air Pressure on the Diver.—When a diver de scends into the sea, the extra air pressure to which he is subjected is instantly transmitted to the whole inside of his body. At great depths his blood vessels and tissues become saturated with nitro gen. It should be remembered that a gas in contact with a liquid on which it has no chemical action is absorbed by the liquid in amounts proportional to the pressure of the gas at the time. In the lungs we have the blood practically in contact with the air, which consists of three important gases—oxygen, nitrogen and carbon dioxide. Of these, the nitrogen alone can remain and accumulate in the blood ; the oxygen is used up by the tissues, and the breathing prevents the pressure of carbon dioxide from in creasing, so that the only gas which accumulates in abnormal quantity in the blood when the diver is under pressure is the nitrogen.

When gas is forced into a soda-water bottle under pressure, the water appears to be unchanged so long as the pressure is kept up, but the moment the pressure is reduced, by the removal of the cork, we see the gas come bubbling off the liquid. J. S. Haldane has applied the analogy to diving. He says : "The diver is the soda-water bottle, and his blood the fluid in the bottle. As the diver descends, nitrogen under pressure is forced into contact with his blood, which takes up the nitrogen from the air. So long as he stays below under that pressure, his blood appears to be unaltered; when however, he rises, the excess of nitrogen that the blood has taken up begins slowly to bubble off ; if the blood were as fluid as water, it would come off as rapidly as from the soda water. For tunately for the diver, the blood is a thickish, albuminous fluid, in which bubbles do not readily form, and, as far as we can see, it can retain about twice the amount in solution that water can keep at any given pressure. Every diver knows that it is quite safe to come up from a depth of five or six fathoms to the surface as quickly as he likes ; the reason for this will now be easily under stood, since at such a depth the blood has only twice as much nitrogen in it as it has on the surface, and, therefore, bubbles are unlikely to form. If, however, the diver has been for any consid erable time at, say, 18o f t., and then comes up too quickly, it is almost certain that bubbles will form and cause serious symptoms, such as paralysis of the legs (diver's palsy), severe pains in the joints and muscles, etc. Not only is the air taken up by the blood, but the tissues of the body also get saturated with it. In the case of the blood, the saturation is very quick; it is probable, indeed, that the blood leaving the lungs is always saturated to the existing pressure, but the tissues take up the gas at a much slower rate— a rate which depends on the blood supply. Where this is good, as in the brain and spinal cord, the saturation is quick, but in the fibrous tissues about the joints, etc., saturation is very slow. Those tissues which are saturated quickly also give up their surplus nitro gen quickly, and those which saturate slowly also desaturate slowly." In ascending, the diver is decompressing himself, and it is this gradual decompression that is the most important factor in the prevention of accidents from the formation of bubbles of nitro gen. The dangers are to be avoided by working to the following schedule drawn up by Prof. Haldane, during which there is but little chance of the diver getting dangerously saturated with nitro gen. It is important that the diver descend as fast as his air supply will allow him, for every minute spent in descending is time lost, since his body is becoming saturated.

Compressed Air Illness.

Although the rules laid down are calculated completely to prevent compressed air illness, cases do sometimes occur, owing to accidents or mistakes, where the diver comes up too quickly from deep water. In such cases, whether the diver has already shown symptoms of compressed air illness or not, he should be sent down again without delay to the depth at which he has been working, and kept there for five minutes, after which he can start to come up again at the following rates:— On some deep diving operations, however, a Siebe-Gorman Re compression chamber, as fig. 9, is provided, the use of which is a much better and more comfortable method of treatment than sending the diver into deep water again. This chamber is of steel, provided with a bench on which the diver can sit or lie, electric light, telephone, etc. Windows are provided through which the diver can be watched during the process of decompression ; a small hand air-lock attached to the chamber allows refreshments, etc., to be passed into him. It is usually found sufficient to raise the pressure in the chamber to 30 lb., but it should never exceed 45 lb. As soon as the diver is relieved of any symptoms, the pres sure is allowed to fall at the following rates:— Helium and Oxygen for Deep Sea Diving.—Some years ago the proposal was made by Prof. Elihu Thomson, F.R.S., of Swampscott, Mass., U.S.A., to use helium in place of nitrogen in the atmosphere supplied to divers engaged in deep sea work, and the practical utility of this suggestion has been demonstrated re cently by experiments conducted at the Government Bureau of Mines, U.S.A. Helium has a solubility in water nearly 4o% less than nitrogen ; therefore, during exposure to compressed air, nearly 40% less gas will be dissolved in the watery part of the body. The rate of diffusion of helium is 2.64 times that of nitrogen, its molecular weight being 4 against 28 for nitrogen. Helium will thus escape from the lungs much more quickly than nitrogen during decompression. Experiments on animals have so far shown that the safe decomposition time for helium and nitrogen is some where about 1 to 3 or 4. To reduce the decompression periods to one-third or one-fourth would be a very great advantage.

Greatest Depths for Useful Work.

The greatest depth at which useful work has been accomplished by divers is 2 75f t. This was at the salvage of the U.S.A. submarine "F4," sunk off Hono lulu, by divers of the United States Navy using the British Ad miralty decompression system described in the present article. The Spanish diver, Erostarbe, recovered I9,o00 worth of silver bars from a depth of 182ft. Siebe, Gorman & Co.'s chief diver, the late Alexander Lambert, salved I70,0oo worth of Spanish gold coin from the wreck of the "Alphonse XII" sunk in 165ft. off Las Palmas. W. Ridyard brought up Iso.000 worth of dollars from the "Hamilla Mitchell" lying in i 5of t. of water. These are a few examples of treasury recovery notable by reason of the great depths involved. But there have been many cases where far larger sums have been recovered from lesser depths, e.g., the case of the "Laurentic" in 13of t., sunk during the World War, with gold on board to the value of five million pounds sterling, all but £40,00o worth of which was recovered by British naval divers. 'Then there is the case of the "Oceanic" from which specie, etc., to the value of f 700,00o was salved by divers.The sponge divers of the Mediterranean work at a maximum depth of about i 5of t., but they make exceedingly short stays on the bottom, and so, in most cases, avoid risk of pressure troubles. The pearl divers of Australia usually work,at about 12oft. Sub marine operations on the great majority of harbour, dock and bridge works are conducted at depths of from 4o to 8oft. The weighted tools employed by divers differ very little from those used by workmen on terra firma. Pneumatic tools, worked by compressed air conveyed from the surface through flexible tubes, are great aids, particularly in rock-blasting work.

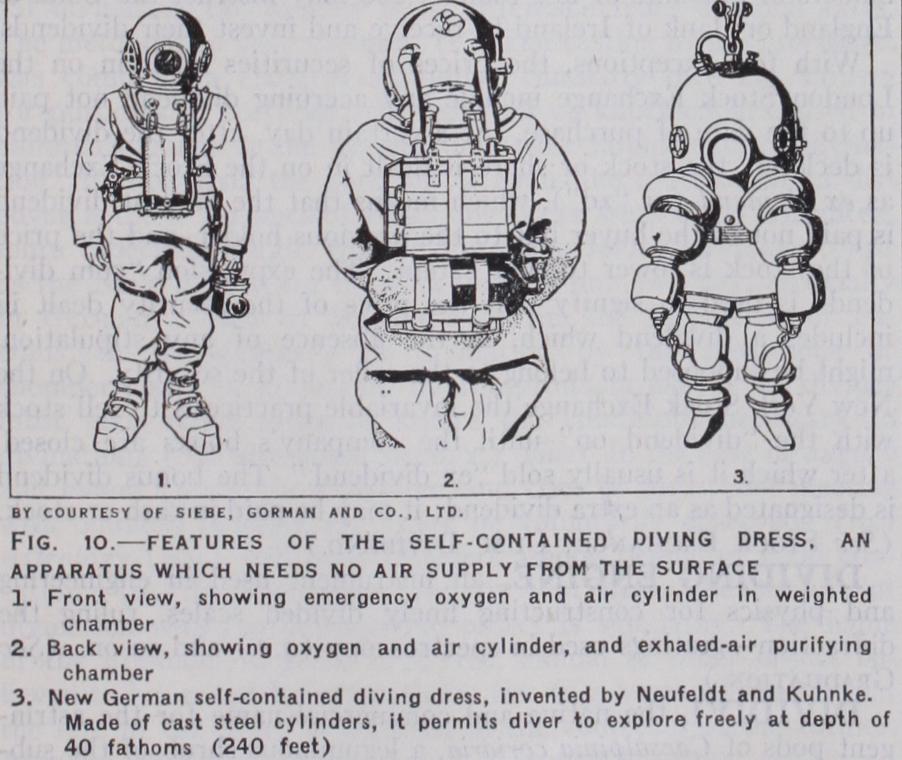

Self-contained Diving Apparatus (fig. io).—The first really practicable self-contained diving apparatus was designed by H. A. Fleuss, working in conjunction with Siebe and Gorman, about 50 years ago. The original apparatus enabled a diver to do good work in the flooded Severn tunnel in 1882. The diver on that occasion had to travel nearly a quarter of a mile through the workings—encountering all sorts of obstacles, floating timber, etc., on his journey—to a heading in which he had to close an iron door and a sluice valve. Later, Fleuss and R. H. Davis improved the apparatus considerably. The apparatus supplies a factitious, but perfectly respirable air by means of regenerating devices, thus making him independent of the surface. His dress, helmet and boots are of the ordinary patterns. Attached to a leather equipment carried on his back is (1) a cylinder of oxygen and air in certain proportions (it is dangerous to breathe pure oxy gen at pressures above one atmosphere plus, hence the dilution) ; (2) a reducing valve connected to the cylinder, and passing the gas into the helmet through a tube connection at the requisite pressure and volume; (3) a watertight chamber, containing caustic soda, also connected by tube to the helmet. The diver's exhaled air is passed through the caustic soda, which takes up the carbonic acid, and, thus purified, comes back into the helmet where it mixes with the fresh oxygen and air which is constantly passing from the cylinder. This process of regeneration goes on auto matically for from 45 minutes to two hours, according to the depth at which the diver may be working. The apparatus can be used at depths down to I 5of t.

Recently, Neufeldt and Kuhnke have constructed a diving dress of steel and aluminium alloy, which, they claim, enables the wearer to do the work of a diver in the ordinary (flexible) dress. This diving suit is independent of outside air supply, and is de signed to withstand the pressure due to the head of water at which the diver is working. The diver, therefore, breathes air at normal atmospheric pressure, thereby eliminating the effects due to excessive air pressure. Connection with the ship can be main tained by a cable and communication effected by a telephone. A diver equipped with the dress has recently (Aug. 1928) worked on the wreck of the Belgian steamer "Elizabethville," sunk in 1917 off Belle Isle, at a depth of 240 feet.

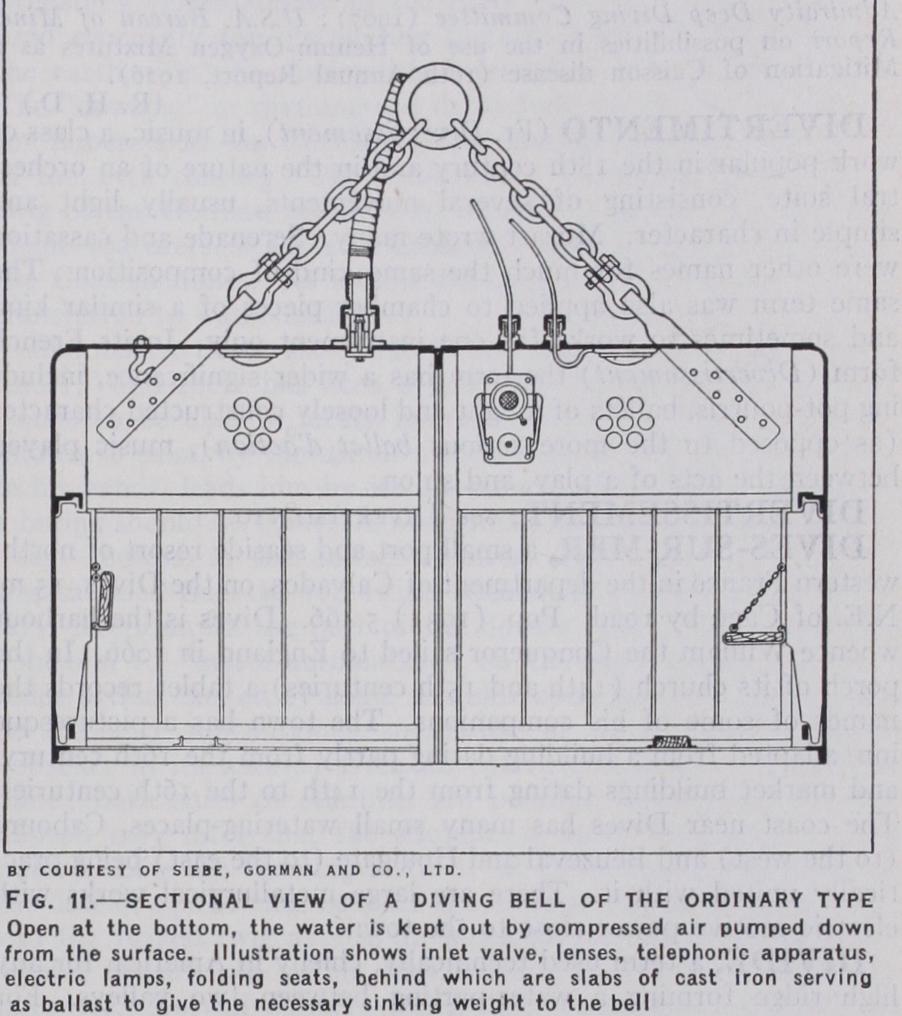

Diving Bells.—The first designer of the diving bell may have received inspiration from the water spider which makes its home in a bell-shaped chamber of silk, anchored, orifice downwards, by silken threads to water-weeds, etc. The hairs which cover the hinder part of the spider's body are long and hooked at the ends, and have the power of entangling air, so that, when it dives be neath the surface, the insect is partially enveloped in a bubble. The bell when first made is, of course, full of water. To expel the water, the spider disengages the bubble of air inside the bell, and so displaces a little water, the operation being repeated until the water is replaced entirely by air, the latter being re-oxygenated by the same process. Pressure of water increases with its depth. Sink a diving bell to a depth of, say 33ft., and the air inside it will be compressed to about one-half its original volume, and the bell itself will be half filled with water. But keep up a supply of air at a pressure a little above that which is equal to the depth at which the bell is submerged, and you will not only keep the water down to the lower edge of the bell, you will also ventilate it and enable its occupants to work for hours at a stretch.

Tradition gives Roger Bacon, in 125o, the credit of being the originator of the diving bell, but actual records are not to be had. Of the records preserved to us, the most trustworthy is the description in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 1717, of Dr. Edmund Halley's bell, constructed of wood, and supplied with air by means of two closed barrels, with a hole in the bottom, and with a leathern tube, connected at the top, the open end of the tube falling below the bottom of the barrel. The barrels were lowered and raised alternately. When the tubes were taken into the bell, the pressure of water, acting through the hole in the bottom of the barrel, forced the enclosed air into the bell.

Fig. 11 illustrates one of several Siebe-Gorman ordinary diving bells, built of steel, as used during the construction of the Na tional Harbour at Dover. Each measured 17ft. long by Io%ft. wide by 7ft. high, and weighed 35 tons. It was lighted electrically, and fitted with telephonic apparatus which enabled the bell divers to converse with the engineers and crane and compressor attend ants at the surface. Air was supplied to the bell by a steam driven compressor housed on the gantry which carried the travel ling cranes for lowering and raising the bell through the water to a maximum depth of 6of t., and also for lowering the concrete blocks. The air tube for the compressor was connected to a non-return air inlet valve fitted in the crown of the bell. As in the case of the diving dress, an adequate supply of air at the right pressure is maintained to ensure proper ventilation of the bell, the excess escaping at the lower edge of the latter. The bell divers were employed in levelling the sea-bed in readiness to receive the blocks, which weighed 4o tons apiece. Having levelled one sec tion, the bell was moved to the next. The blocks were then powered, and were placed in position by helmet divers. The bell divers, clad in woollen suits and watertight thigh boots, worked in two-hour to three-hour shifts. The cost of such a bell, with air compressor, telephone and electric lamps, is about £ 2,000.

The air-lock diving bell comprises a steel working chamber similar to the ordinary diving bell already described, with the ad dition of a steel shaft attached to the roof. At the upper end of the shaft is an airtight door, and about 8f t. below this is another similar door, the space between the two forming an air-lock. When the men wish to enter the bell, they pass through the first door and close it after them, and then open a valve and let into the lock compressed air from the working chamber till the pressure is equalized; they then open the second door and pass into the main shaft, closing the door after them. Access to the working chamber is by ladder, secured to the side of the shaft. When returning to the surface, they reverse the operation, opening the lower door, entering the lock and closing the door again; then opening a valve to release the air pressure, when the upper door is opened and the men emerge to atmosphere. Some bells of this type are fitted with two shafts each with its air-lock—one for the passage of the bell men, the other for materials.

See R. H. Davis, A Diving Manual (192o) ; Report of British Admiralty Deep Diving Committee (1907) ; U.S.A. Bureau of Mines Report on possibilities in the use of Helium-Oxygen Mixtures as a Mitigation of Caisson disease (i6th Annual Report, 1926).

(R. H. D.)