Historic Dances

HISTORIC DANCES, 15TH-19TH CENTURY France and Italy.—Italy, in the r 5th century, saw the renais sance of dancing, and France may be said to have been the nursery of the modern art, though comparatively few modern dances are really French in origin. The national dances of other countries were brought to France, studied systematically, and made perfect there. An English or a Bohemian dance, practised only amongst peasants, would be taken to France, polished and perfected, and would at last find its way back to its own country, no more recognizable than a piece of elegant cloth when it returns from the printer to the place from which as "grey" material it was sent. The fact that the terminology of dancing is almost entirely French is a sufficient indication of the origin of the rules that govern it.

The earliest dances that bear any relation to the modern art are probably the danses basses and danses hautes of the r6th century. The danse basse was the dance of the court of Charles IX. and of good society, the steps being very grave and dignified, not to say solemn, and the accompaniment a psalm tune. The danses hautes or baladines had a skipping step, and were practised only by clowns and country people. More lively dances, such as the Gaillarde and Volta, were introduced into France from Italy by Catherine de' Medici, but even in these the interest was chiefly spectacular. Other dances of the same period were the Branle (afterwards corrupted to Braule, and known in England as the Brawle)—a kind of generic dance which was capable of an almost infinite amount of variety. Thus there were imitative mimes, such as the Branles des Ermites, Branles des flambeaux and the Branles des lavandieres. The Branle in its original form had steps like the Allemande.

Perhaps the most famous and stately dance of this period was the Pavane (of Spanish origin), which is very fully described in Tabouret's Orchesographie, the earliest work in which a dance is found minutely described. The Pavane, which was really more a procession than a dance, must have been a very gorgeous and noble sight, and it was perfectly suited to the dress of the period, the stiff brocades of the ladies and the swords and heavily plumed hats of the gentlemen being displayed in its simple and dignified measures to great advantage.

In the

Pavane and Branle, and in nearly all the dances of the i 7th and t 8th centuries, the practice of kissing formed a not unim portant part, and seems to have added greatly to the popularity of the pastime. Another extremely popular dance was the Sara band, which, however, died out of ter the i 7th century. It was originally a Spanish dance, but enjoyed an enormous success for a time in France. Every dance at that time had its own tune or tunes, which were called by its own name, and of the Saraband the chevalier de Grammont wrote that "it either charmed or an noyed everyone, for all the guitarists of the court began to learn it, and God only knows the universal twanging that followed." Vauquelin des Yveteaux, in his Both year, desired to die to the tune of the Saraband, "so that his soul might pass away sweetly." The Courante was a court dance performed on tiptoe with slightly jumping steps and many bows and curtseys. The minuet and the waltz were both in some degree derived from it, and it had much in common with the famous Seguidilla of Spain. It was a favourite dance of Louis XIV., who was an adept in the art, and it was regarded in his time as of such importance that a noble man's education could hardly have been said to be begun until he had mastered the Courante.The dance which the French brought to the greatest perfection —which many, indeed, regard as the fine flower of art—was the Minuet. Its origin, as a rustic dance, is not less antique than that of the other dances from which the modern art has been evolved. It was originally a branle of Poitou, derived from the Courante. It came to Paris in t 65o and was first set to music by Lully. It was at first a gay and lively dance, but on being brought to court it soon lost its sportive character and became grave and dignified. It is mentioned by Beauchamps, the father of dancing masters, who flourished in Louis XIV.'s reign, and also by Blondy, his pupil; but it was Pecour who really gave the minuet its pop ularity, and although it was improved and made perfect by Daub erval, Gardel, Marcel and Vestris, it was in Louis XV.'s reign that it saw its golden age. It was then a dance for two in moderate triple time, and was generally followed by the gavotte. Afterwards the minuet was considerably developed, and with the gavotte be came chiefly a stage dance and a means of display ; but it should be remembered that the minuets which are now danced on the stage are generally highly elaborated with a view to their spec tacular effect, and have imported into them steps and figures which do not belong to the minuet at all, but are borrowed from all kinds of other dances. The original court minuet was a grave and simple dance, although it did not retain its simplicity for long. But when it became elaborated it was glorified and moulded into a perfect expression of an age in which deportment was most sedulously cultivated and most brilliantly polished. The "languishing eye and smiling mouth" had their due effect in the minuet ; it was a school for chivalry, courtesy and ceremony; the hundred slow graceful movements and curtseys, the pauses which had to be filled by neatly-turned compliments, the beauty and bravery of attire—all were eloquent of graces and outward refinements which we cannot boast now. The fact that the measure of the minuet has become incorporated in the structure of the symphony shows how important was its place in the polite world.

The Gavotte, which was often danced as a pendant to the min uet, was also originally a peasant's dance, a danse des Gavots, and consisted chiefly of kissing and capering. It also became stiff and artificial, and in the later and more prudish half of the i8th century the ladies received bouquets instead of kisses in dancing the gavotte. It rapidly became a stage dance, and it has never been restored to the ballroom. Gretry attempted to revive it, but his arrangement never became popular.

Other dances which were naturalized in France were the Ecos saise, popular in i 760; the Cotillon, fashionable under Charles X., derived from the peasant branles and danced by ladies in short skirts; the Galop, imported from Germany; the Lancers, invented by Laborde in t 836 ; the Polka, brought by a dancing-master from Prague in 184o; the Schottische, also Bohemian, first introduced in 1844 ; the Bourree, or French clog-dance; the Quadrille, known in the i8th century as the Contre-danse; and the Waltz, which was danced as a volte by Henry III. of France, but only became popular in the beginning of the i9th century. We shall return to the history of some of these later dances in discussing the dances at present in use.

Spain.—If France has been the nursery and school of the art of dancing, Spain is its true home. There it is part of the national life, the inevitable expression of the gay, contented, irresponsible, sunburnt nature of the people. The form of Spanish dances has hardly changed ; some of them are of great antiquity, and may be traced back with hardly a break to the performances in ancient Rome of the famous dancing-girls of Cadiz. The connection is lost during the period of the Arab invasion, but the art was not neglected, and Jovellanos suggests that it took refuge in Asturias. At any rate, dances of the Loth and Lath centuries have been pre served uncorrupted. The earliest dances known were the Turdion, the Gibidana, the Pie-de-gibao, and (later) the Madama Orleans, the Alemana and the Pavana. Under Philip IV. theatrical dancing was in high popularity, and ballets were organized with extraor dinary magnificence of decoration and costume. They supplanted the national dances, and the Zarabanda and Chacona were prac tically extinct in the i8th century. It is at this period that the famous modern Spanish dances, the Bolero, Seguidilla and the Fandango, first appear.

Of these the

Fandango is the most important. It is danced by two people in 6-8 time, beginning slowly and tenderly, the rhythm marked by the click of castanets, the snapping of the fingers and the stamping of feet, and the speed gradually increasing until a whirl of exaltation is reached. A feature of the Fandango and also of the Seguidilla is a sudden pause of the music towards the end of each measure, upon which the dancers stand rigid in the attitudes in which the stopping of the music found them, and only move again when the music is resumed. M. Vuillier, in his History of Dancing, gives the following description of the Fan dango:—"Like an electric shock, the notes of the Fandango ani mate all hearts. Men and women, young and old, acknowledge the power of this air over the ears and soul of every Spaniard. The young men spring to their places, rattling castanets or imitating their sound by snapping their fingers. The girls are remarkable for the willowy languor and lightness of their move ments, the voluptuousness of their attitudes—beating the exactest time with tapping heels. Partners tease and entreat and pursue each other by turns. Suddenly the music stops, and each dancer shows his skill by remaining absolutely motionless, bounding again into the full life of the Fandango as the orchestra strikes up. The sound of the guitar, the violin, the rapid tic-tac of heels (taconeos), the crack of fingers and castanets, the supple swaying of the dancers, fill the spectator with ecstacy. The measure whirls along in a rapid triple time. Spangles glitter ; the sharp clankbf ivory and ebony castanets beats out the cadence of strange, throb bing, deepening notes—assonances unknown to music, but cu riously characteristic, effective and intoxicating. Amidst the rustle of silks, smiles gleam over white teeth, dark eyes sparkle and droop and flash up again in flame. All is flutter and glitter, grace and animation—quivering, sonorous, passionate, seductive." The Bolero is a comparatively modern dance, having been in vented by Sebastian Cerezo, a celebrated dancer of the time of King Charles III. It is remarkable for the free use made in it of the arms, and is said to be derived from the ancient Zarabanda, a violent and licentious dance, which has entirely disappeared, and with which the later Saraband has practically nothing in common. The step of the Bolero is low and gliding but well marked. It is danced by one or more couples. The Seguidilla is hardly less ancient than the Fandango, which it resembles. Every province in Spain has its own Seguidilla, and the dance is accom panied by coplas, or verses, which are sung either to traditional melodies or to the tunes of local composers; indeed, the national music of Spain consists largely of these coplas.

The Jota is the national dance of Aragon, a lively and splendid, but withal dignified and reticent, dance derived from the i6th century Passacaille. It is still used as a religious dance. The Cachuca is a light and graceful dance in triple time. It is per formed by a single dancer of either sex. The head and shoulders play an important part in the movements of this dance. Other provincial dances now in existence are the Jaleo de Jerez, a whirl ing measure performed by gipsies, the Palotea, the Polo, the Gallegada, the Muyneria, the Habas Verdes, the Zapateado, the Zorongo, the Vito, the Tirano and the Tripola Trapola. Most of these dances are named either after the places where they are danced or after the composers who have invented tunes for them. Many of them are but slight variations from the Fandango and Seguidilla.

Great Britain.

The history of court dancing in Great Britain is practically the same as that of France, and need not occupy much of our attention here. But there are strictly national dances still in existence which are quite peculiar to the country, and may be traced back to the dances and games of the Saxon gleemen. The Egg dance and the Carole were both Saxon dances, the Carole being a Yule-tide festivity, of which the present-day Christmas carol is a remnant.The oldest dances which remain unchanged in England are the Morris dances, which were introduced in the time of Edward III. (See MORRIS DANCE.) Dancing practically disappeared during the Puritan regime, but with the Restoration it again became popular. It underwent no considerable developments, however, until the reign of Queen Anne, when the glories of Bath were revived in the beginning of the i8th century, and Beau Nash drew up his famous codes of rules for the regulation of dress and manners, and founded the balls in which the polite French dances completely eclipsed the simpler English ones.

The only true national dances of Scotland are reels, strathspeys and flings, while in Ireland there is but one dance—the jig, which is there, however, found in many varieties and expressive of many shades of emotion, from the maddest gaiety to the wildest lament. Curiously enough, although the Welsh dance often, they have no strictly national dances.

Popular Dances of Universal Importance.

The Waltz is no doubt the most popular of the i 9th century dances. Its origin is a much-debated subject, the French, Italians and Bavarians each claiming for their respective countries the honour of having given birth to it. As a matter of fact the waltz, as it is 'haw danced, comes from Germany; but it is equally true that its real origin is French, since it is a development of the V olte, which in its turn came from the Lavolta of Provence, one of the most ancient of French dances. The Lavolta was fashionable in the i6th century and was the delight of the Valois court. The V olte danced by Henry III. was really a Valse a deux pas; and Castil Blaze says that "the waltz which we took again from the Ger mans in 1795 had been a French dance for four hundred years." The change, it is true, came upon it during its visit to Germany, hence the theory of its German origin. The first German waltz tune is dated 17 7o— "Ach! du lieber Augustin." It was first danced at the Paris opera in 1793, in Gardel's ballet La Danso manie. It was introduced to English ballrooms in 1812, when it roused a storm of ridicule and opposition, but it became popular when danced at Almack's by the emperor Alexander in 1816. The waltz a trois temps has a sliding step in which the movements of the knees play an important part. The tempo is moderate, so as to allow three distinct movements on the three beats of each bar; and the waltz is written in 3-4 time and in eight-bar sentences. Walking up and down the room and occasionally breaking into the step of the dance is not true waltzing, and the habit of pushing one's partner backwards along the room is an entirely English one. But the dancer must be able to waltz equally well in all directions, pivoting and crossing the feet when necessary in the reverse turn. It need hardly be said that the feet should never leave the floor in the true waltz. Gungl, Waldteufel and the Strauss family may be said to have moulded the modern waltz to its present form by their rhythmical and agreeable compositions. There are variations which include hopping and lurching steps; these are degradations, and foreign to the spirit of the true waltz.The Quadrille is of some antiquity, and a dance of this kind was first brought to England from Normandy by William the Conqueror, and was common all over Europe in the i6th and 17th centuries. The term quadrille means a kind of card game, and the dance is supposed to be in some way connected with the game. A species of quadrille appeared in a French ballet in and since that time the dance has gone by that name. It then consisted of very elaborate steps, which in England have been simplified until the degenerate practice has become common of walking through the dance. The quadrille, properly danced, has many of the graces of the minuet. It is often stated that the square dance is of modern French origin. This is incorrect, and probably arises from a mistaken identification of the terms quad rille and square dance. "Dull Sir John" and "Faine I would," were square dances popular in England 30o years ago.

An account of the country-dance, with the names of some of the old dance-tunes, has been given above. The word is not, as has been supposed, an adaptation of the French contre-danse, neither is the dance itself French in origin. According to the New English Dictionary, contre-danse is a corruption of "country-dance," pos sibly due to a peculiar feature of many of such dances, like Sir Roger de Coverley, where the partners are drawn up in lines op posite to each other. The English "country-dances" were intro duced into France in the early part of the i8th century and became popular; later French modifications were brought back to England under the French form of the name, and this, no doubt, caused the long-accepted but confused derivation.

The Lancers were invented by Laborde in Paris in 1836. They were brought over to England in 185o, and were made fashionable by Madame Sacre at her classes in Hanover Square Rooms.

The Polka, the chief of the Bohemian national dances, was adopted by society in 1835 at Prague. Josef Neruda had seen a peasant girl dancing and singing the polka, and had noted down the tune and the steps. From Prague it readily spread to Vienna, and was introduced to Paris by Cellarius, a dancing-master, who gave it at the Odeon in 184o. It took the public by storm, and spread like an infection through England and America. Every thing was named after the polka, from public-houses to articles of dress. Mr. Punch exerted his wit on the subject weekly, and even The Times complained that its French correspondence was interrupted, since the polka had taken the place of politics in Paris. The true polka has three slightly jumping steps, danced on the first three beats of a four-quaver bar, the last beat of which is employed as a rest while the toe of the unemployed foot is drawn up against the heel of the other.

The Galop is strictly speaking a Hungarian dance, which be came popular in Paris in 183o. But some kind of a dance corre sponding to the galop was always indulged in after V oltes and Contre-danses, as a relief from their constrained measures.

The Barn-dance is no doubt of American origin, its height of popularity being toward the end of the 1 gth century. It was cus tomary for the farmer who wished to build a new barn to call in his neighbours for a "working" and finish the job within a short time, after which a dance was "thrown." The dance is still very popular in certain rural sections, and does not necessarily confine itself to new or empty barns. The square dance, or some form of group dancing, is executed to the accompaniment of a two- or three-piece string band or the neighbouring fiddle.

The Paul Jones is one of the many "sets" that comprise an evening of barn-dancing. A number of couples are required for the performance as well as a "caller" who gives direction as to the action of each couple.

The Washington Post belongs to America.

The Polka-Mazurka is extremely popular in Vienna and Buda pest, and is a favourite theme with Hungarian composers. The six movements of this dance occupy two bars of 3-4 time, and consist of a mazurka step joined to the polka. It is of Polish origin.

The Polonaise and Mazurka are both Polish dances, and are still fashionable in Russia and Poland. Every State ball in Russia is opened with the ceremonious Polonaise.

The Schottische, a kind of modified polka, was "created" by Markowski, who was the proprietor of a famous dancing academy in 185o. The Highland Schottische is a fling. The Fling and Reel are Celtic dances, and form the national dances of Scotland and Denmark. They are complicated measures of a studied and classical order, in which free use is made of the arms and of cries and stampings. The Strathspey is a slow and grandiose modifica tion of the Reel.

Sir Roger de Coverley is

the only one of the old English social dances which has survived to the present day, and it is frequently danced at the conclusion of the less f ormal sort of balls. It is a merry and lively game in which all the company take part, men and women facing each other in two long rows. The dancers are constantly changing places in such a way that if the dance is car ried to its conclusion everyone will have danced with everyone else. The music was first printed in 1685, and is sometimes written in 2-4 time, sometimes in 6-8 time, and sometimes in 3-9 time.The Cotillon is a modern development of the French dance of the same name referred to above. It is an extremely elaborate dance, in which a great many toys and accessories are employed; hundreds of figures may be contrived for it, in which presents, toys, lighted tapers, biscuits, air-balloons and hurdles are used.

Ballet.—The modern ballet (q.v.) would seem to have been first produced on a considerable scale in 1489 at Tortona, before Duke Galeazzo of Milan. It soon became a common amusement on great occasions at the European courts. The ordinary length was five acts, each containing several entrees, and each entree con taining several quadrilles.

the old division of t

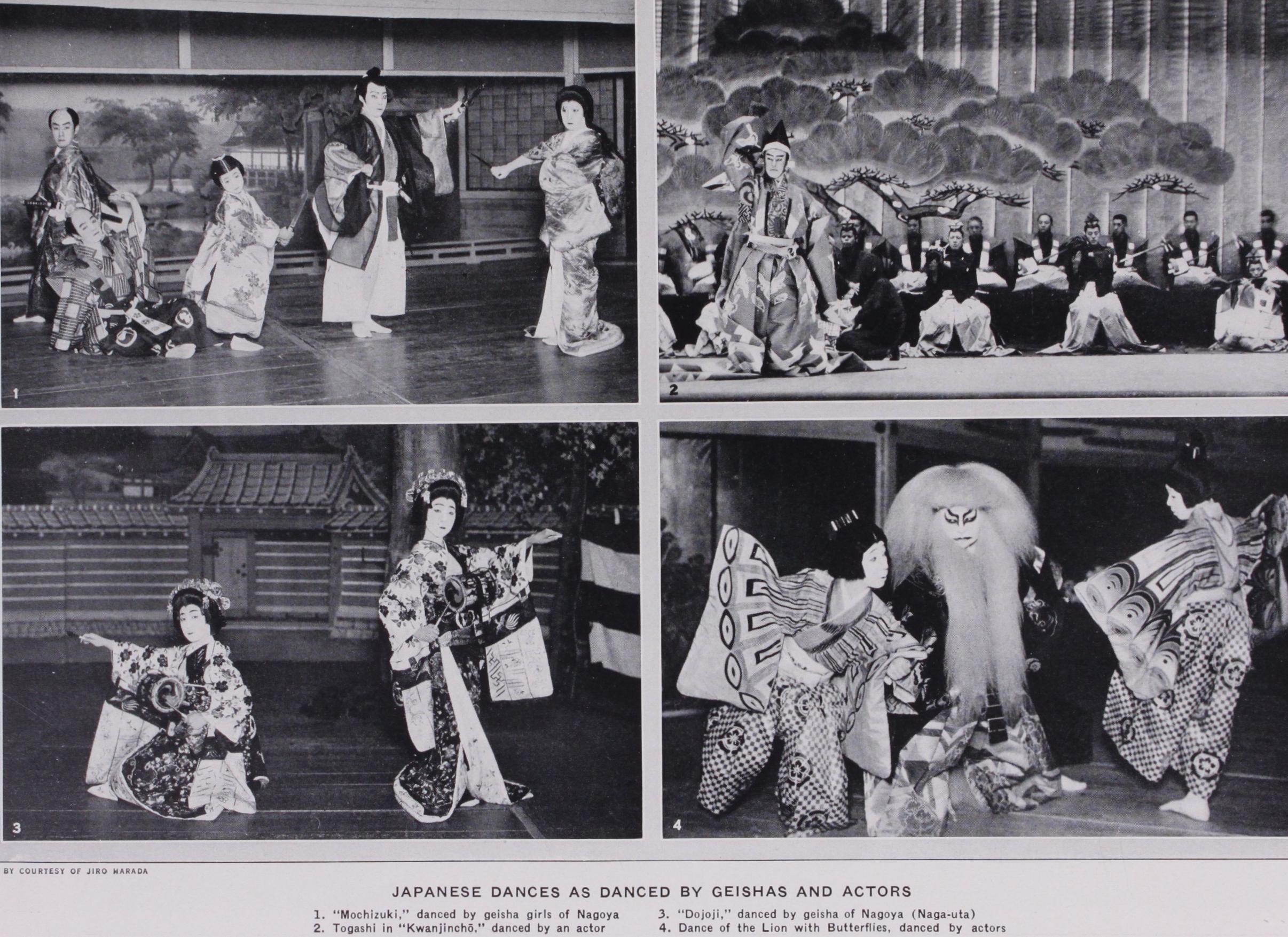

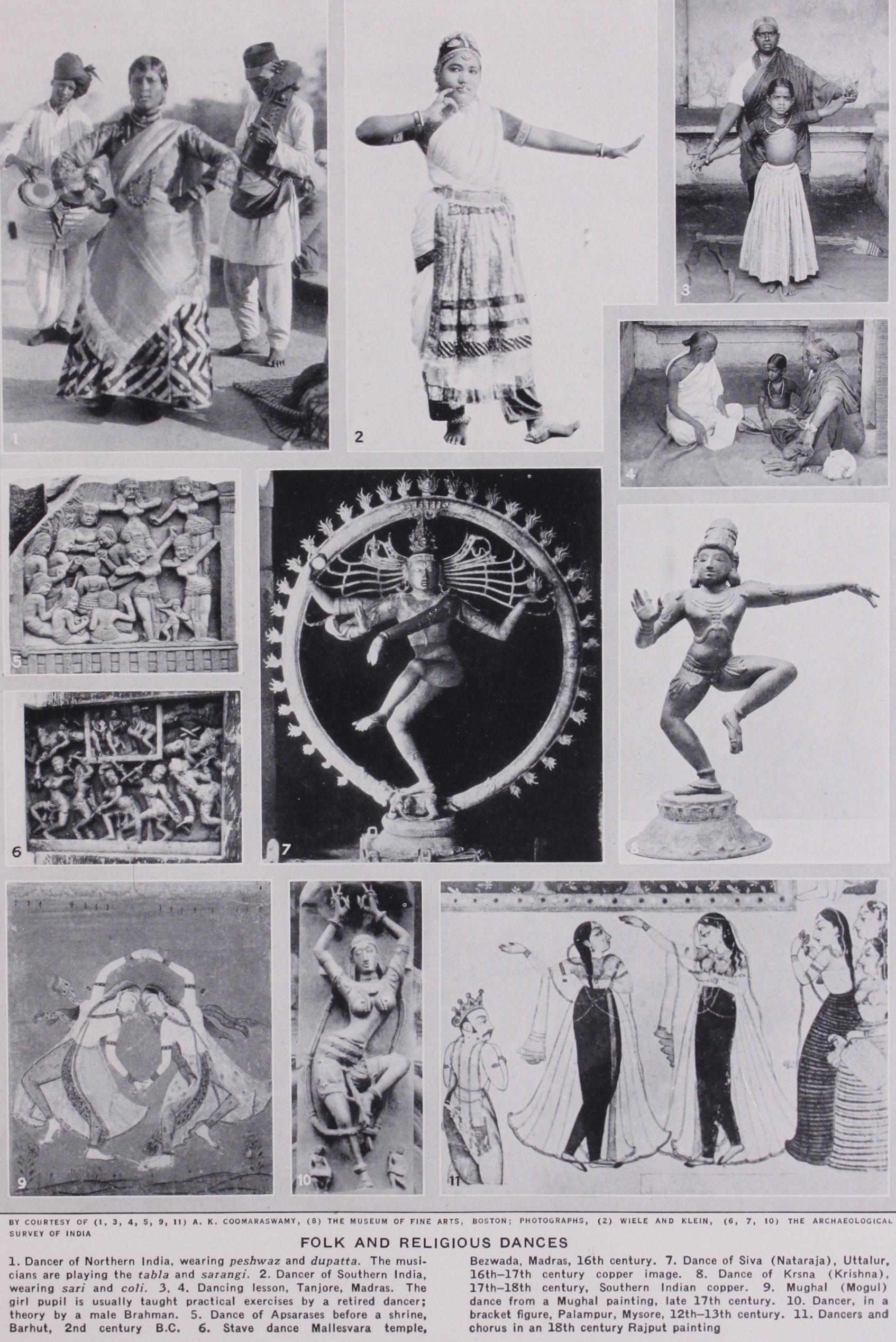

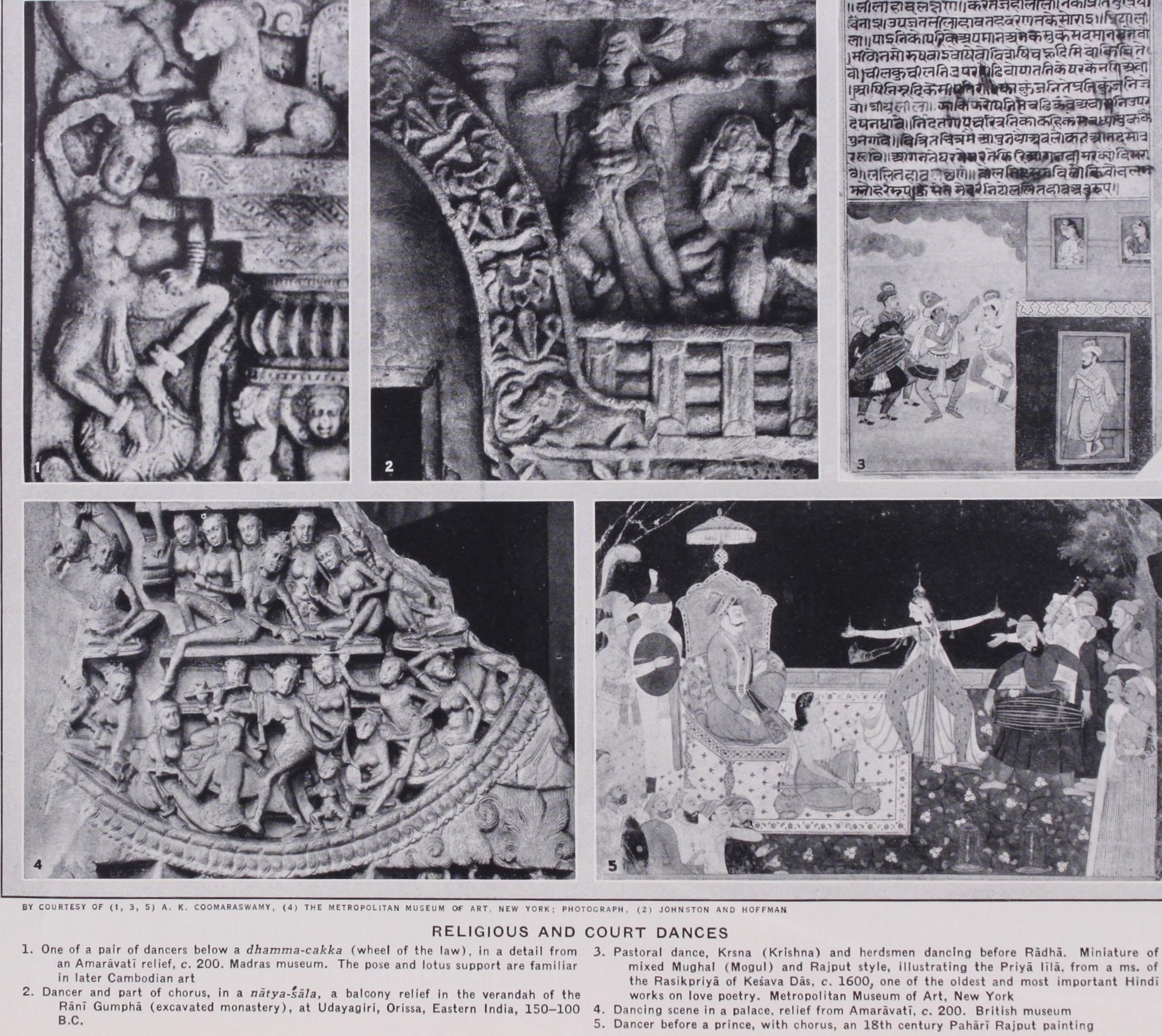

he Ars Gymnastica into palaestrica and saltatoria, and of the latter into cubistica, sphaeristica and orchestica, see the learned work of Hieronymus Mercurialis, De arte Gymnastica (Amsterdam, 1572). Cubistic was the art of throwing somersaults, and is described minutely by Tuccaro in his Trois Dialogues (Paris, 1599). Sphaeristic included several complex games at ball and tilting—the Greek thpwcos, and the Roman trigonalis and paganica. Orchestic, divided by Plutarch into latio, figura and indicatio, was really imitative dancing, the "silent poetry" of Simonides. The importance of the xapovoi.da or hand-movement is indicated by Ovid:—"Si vox est, canta ; si mollia brachia, salta." For further information as to modern dancing, see Rameau's Le maitre a danser (x726) ; Querlon's Le triomphe des graces (1774) ; Cahousac, La danse ancienne et moderne (1754) ; Vuillier, History of Dancing (Eng. trans., 1897) ; Giraudet, Traite de la danse (i9oo).(A. B. F. Y.) The dance in Japan has its origin in her mythical age. Accord ing to the 8th century Kojiki, when Amaterasu, the sun-goddess, retired in high dudgeon to a cavern, Ama-no-Uzumeno-mikoto danced at the cavern's mouth to lure her out. Kagura, the sacred dance of today, is traced back to this incident by the native literati. Records speak of the emperor Inkyo playing on a wa-gon (Japanese native koto) and the empress dancing at the imperial banquet given in 419 on the completion of their new palace build ing. In the Orient the dance is as old as history, and when some 7,000 Chinese families emigrated to Japan in 54o it is not to be doubted that they brought with them their cherished national custom. In 552 a Korean monarch sent a Buddhist mission to Japan and the dance formed a part of their religious ceremony. The old picturesque dance of China and Korea is still executed semi-annually, to the sound of flutes and waving of feathers in worship by the followers of Confucius. The dance became defi nitely established as a Japanese institution by Ashikaga Shogun Yoshimitsu's 0363-94) school for dancing, and the Shogun him self incorporated many historical themes of China into dramatic dances. With the invention of the N5 play by Kwanami Kiot sugu (1406) and its development by his equally famous son, Seami 11/lotokiyo, the dance became closely associated with the national theatre. In the 16th century the fame of the beautiful Okuni popularized the dance among all classes of society. But the tradition begun by her was interrupted in 1643 when, for reasons of public morality, women were forbidden to appear upon the stage; male actors and the priests of Buddha continued the ancient custom of Korea and China. Western ballroom dances, such as waltzes and two-steps, were introduced to Japan in the last quarter of the i9th century and became a fashion for a time, but were soon dropped, and then revived again. (Y. K.) Visitors to Japan generally return deeply impressed with the beauty of cherry blossoms and the charming grace of the geisha girl dance. The dance is performed not only by the geisha and other dancing professionals, but is given in connection with the classical No drama, and it plays an important part in the old style of acting known as kabuki for, as an eminent actor of the old school has said, "an actor without ability to dance is like a wrestler without strength." Sacred dances called kagura, very simple in character, are given by maidens at some shrines, while Buddhist dances, such as Nembutsu-odori, may be seen in connection with some religious observances.

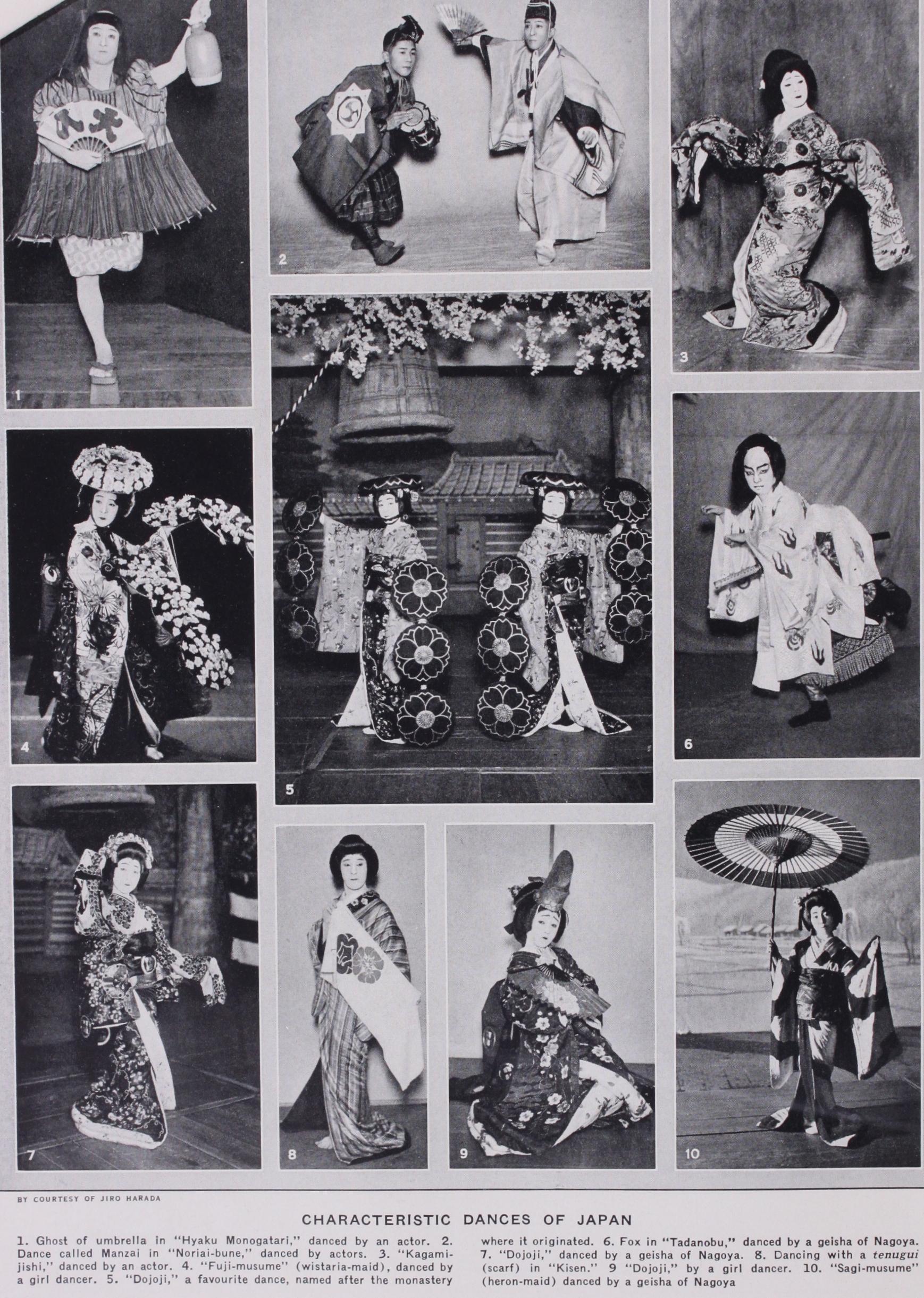

Speaking of the native dance of Japan, three terms are used: mai, odori and furi or shosa, all meaning dance, though technically differentiated. The first has been used to designate the older style of dancing which has been in vogue among the upper class and come to be performed by professionals. It is likened to the graceful movements of the crane at sunrise. The second, which does not appear in literature before the i5th century, has been applied to the dance that was born and has become a fashion among the common people. It means the spontaneous expression of joy with gesture of hands and feet common to all people. The third designates the dance woven into the acting on the stage. Mai may be said to designate a classical, odori a popular and furi a dramatic dance. However, the first may also be classified into two: classical and popular. The classical mai is preserved in the imperial court in connection with traditional observances, or in Shinto shrines as kagura, or in No drama, while the popular mai is practically the same as odori but called mai according to the custom peculiar to certain localities. It is generally main tained that in mai the attitude is characterized by solemnity, the gesture by elegance and refinement, and the movement by an easy and natural flow, while in odori the dance is more natural and free in attitude and movement, and the gesture more active and subtle, with a greater freedom for variation, allowing even a comical or a rustic element to creep in. Furi is enlivened with dramatic quality. However, in many instances the distinction is hard, or even impossible, to draw. Moreover, the three terms may be said to represent different essential elements in the dance, rather than its kinds.

The dance of Japan may generally be divided into two classes: the popular and the special or professional. The former is for the pleasure of the mass of people who may acquire the art in several days or weeks, and it includes such dances as Ise-odori (time-honoured dance in the province of Ise), Tanabata-odori (for the festival of the star Vega) and others connected with popular festivals, as well as such religious dances as Bon-odori (held in summer in memory of the dead), Nembutsu odori (with Buddhist prayers), etc. The professional dances are acquired only by patient and laborious practice, requiring at least several years to master them. Some of these dances consist purely of graceful movements, while others are enlivened with dramatic elements. Those with dramatic elements try to narrate a story in rhythmic movements or to reveal feelings of joy, anger, sorrow, love, hatred, etc., either expressed or suggested in the songs or music played in accompaniment. The songs so used are of different styles, such as naga-uta, tokiwazu and kiyomoto, all rendered to the accompaniment of samisen, the three-stringed musical instru ment, and some with drums and flutes in addition. The songs are descriptive of scenery; narrative of historical or traditional events; accounts of heroes; of love or madness; sometimes they deal with ghosts of men and women, or with the spirit of a lion or of a spider, etc., an effort being often made to transport the I observer to the realm of dreams.

The dramatic dance was originally taught by actors themselves until about the beginning of the i8th century, when it became an independent profession. The pioneers of that profession in Tokyo were Denjiro Shigayama, who was originally an actor, Kwambei Fujima and Senzo Nishikawa, each the founder of his own school or style, followed by other masters who formulated styles of their own, each with a number of followers. The most influential styles of dancing in Tokyo are Fujima-ryu, Hanayagi ryu, and If'akayagi-ryu (ryu meaning style or school) . Those of Kyoto are Inouye-ryu and Shinozaki-ryu; those of Osaka are Nishikawa-ryu, Yamamura-ryu and Umemoto-ryu, while Nagoya is dominated by Nishikawa-ryu. Broadly speaking, the dances in vogue in Tokyo are those with a dramatic element, being bold and active, cheerful and witty in style, more fitting to be per formed by men on the stage than in a room, while those of Nagoya, Kyoto and Osaka, which lay great stress upon the grace and charm of movement, are more appropriate to be seen in a room than on the stage, and performed by female rather than male dancers.

According to a rule, the dancer begins at a point one step be hind the centre of the stage, and brings the dance to a close at the centre with a stamp of the foot. The first step is to be taken with an "active" effect and the last with a "passive" feeling. Generally the dancer, in the course of the performance, describes a shape of a folding fan, which symbolizes prosperity as it spreads out toward the end. In pose, the face or the head of the dancer is considered to stand for heaven, the shoulders for the earth, and the waist for the man, indicating the three most important points to be considered in the dancing, and suggesting the relation of the one towards the others in the order of the universe. How ever, all parts of the body are used to make the dance well bal anced, graceful and effective. While limbs, chiefly arms and hands in an endless variety of graceful sweeps and powerful flourishes, are mainly relied upon for the rhythmic movement, the waist keeps the equilibrium. A fan or a tenugui (scarf) is often used in dancing, being manipulated to suggest all sorts of things as the occasion may require. To give a few examples in common prac tice : an open fan raised gradually in front signifies the rising sun; used in a drinking attitude it may represent a wine cup; a closed fan may be used to suggest a stick, a bow, an arrow, or a gun, etc.; a scarf may be doubled and thrust into the sash to indicate long and short swords worn by a samurai; when redoubled and held on the palm in a smoking attitude it may serve as a pipe ; or it may be made to describe running water by holding one end of it and giving it a quick succession of jerks from one side to the other.

It has been the ideal of some great master dancers of Japan to give the dance dignity, refinement and charm by investing it with idealistic, rather than realistic, quality; to make it suggestive, rather than merely explanatory; to create an interesting design, rather than a conglomeration of decorations. The dance of Japan is unique in many respects, and rich in beauty and tradition as the cherry blossoms that adorn the country in spring. (See