Medical Aspects of Deaf-Mutism

DEAF-MUTISM, MEDICAL ASPECTS OF. Mutism, or dumbness, is almost always due to malformation or disease of the ear. Children learn to speak by imitating those about them who speak. Cases have occurred in which a child with normal hearing, brought up by deaf and dumb guardians in an isolated cottage in the mountains, did not learn to speak until it came into contact with speaking people in a town.

The air vibrations constituting sound are conducted through the outer ear passage to the tympanic membrane, and from this through a chain of three small bones in the middle-ear to the inner ear or labyrinth—the essential part of the organ of hearing. The inner ear itself consists of (I) the cochlea, which is con cerned in hearing, and (2) the vestibule and three semicircular canals, which together are concerned with body equilibrium. (See EAR ; HEARING.) From the inner ear the cochlear and vestib ular nerves pass to the corresponding centres in the brain.

Lesions of the ear producing deafness so great as to cause a child to become mute are almost always situated in the inner ear. Deaf-mutes are usually classified into (A) congenital cases due to error in development of the ears, and (B) acquired cases in which the ears, normal at birth, become diseased in childhood. Less than half the cases of deaf-mutism are congenital.

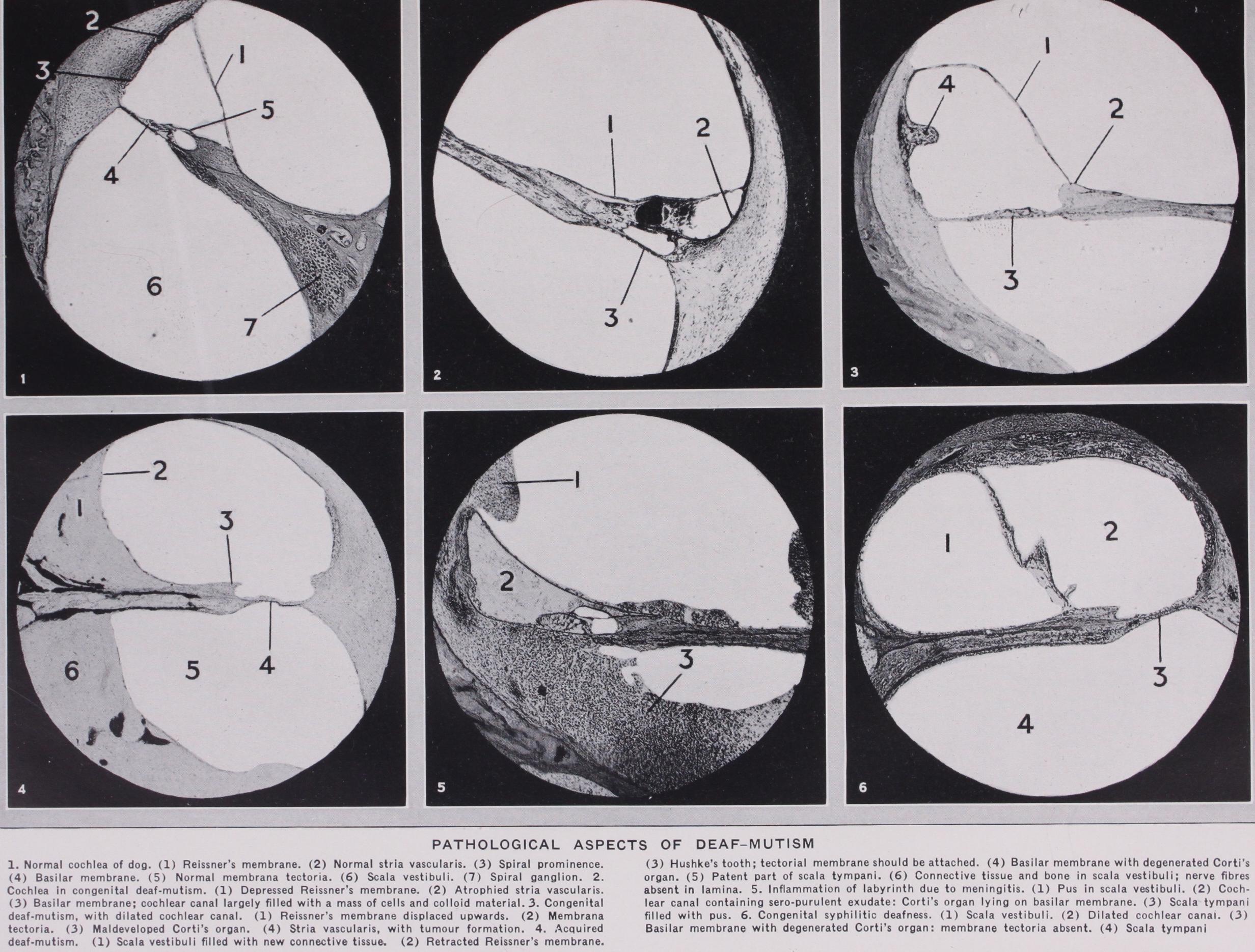

(A) Congenital cases are of two kinds: (I) "endemic" deaf mutism, peculiar to certain districts or countries, e.g., Switzerland, and associated with cretinism and goitre (see CRETINISM). Here, the lesion is in the middle ear; the drum cavity, which should contain air, being more or less filled up by connective tissue or bone. Deafness may not be very marked and the mutism is due mainly to the poor mental development of the patient. (2) The great majority of cases of congenital deafness are due to faulty development of the inner ear. This condition is known as "spo radic" deaf-mutism and is not uncommon in Britain. In the most marked instances the bony and membranous labyrinths are absent, while in the least severe cases only the membranous cochlea is involved. Between these two extremes there are several degrees of maldevelopment. Many of these patients have considerable remains of hearing. The vestibular or balancing apparatus in these cases is usually free from any developmental defect.

(B) Acquired deaf-mutism is due to injury to, or disease of, the inner ear. The deafness may only occur after the child has learnt to speak, but a child which has already acquired fluent speech may quickly become dumb if it loses its hearing, unless special training is begun at the earliest possible moment. The deafness may be produced by such conditions as (I) fracture of the base of the skull, which sometimes results in destruction of the organ of hearing on both sides; these cases are rare. (2) Suppurative disease in the middle and inner ears caused by severe attacks of scarlet fever, measles, or influenza. In these diseases the infection may pass from the nose and throat up the Eustachian tube to the drum cavity, and to the mastoid process which lies behind. (As long as the infection remains localized to the middle ear spaces the deafness is seldom or never so severe as to give rise to deaf-mutism, though the children are often so "hard of hearing" that they cannot be educated efficiently in an ordinary school.) When the infection spreads from the middle to the inner ears, it gives rise to such severe changes that deaf-mutism results. Both the middle and inner ears on each side are filled with pus and, if the patient recovers, the inner ears are more or less obliterated by the formation of connective tissue and new bone, with consequent destruction of the nerve endings of the hearing and balancing apparatus. (3) Meningitis, the infective material finding its way outwards from the brain to the inner ear on each side along the sheath of the nerve of hearing. These children, if and when they recover from meningitis, are not only deaf but have lost their power of balancing for a time and have to learn to walk again. (4) Inherited syphilis which, in Great Britain, is responsible for about 5% of cases of acquired deaf-mutism. In these patients deafness does not occur until the child has, as a rule, reached the age of nine or ten years—a period at which it has of course already learnt to speak. (5) Otosclerosis, in which there is a formation of spongy bone in the normally dense bony capsule of the inner ear that impedes or prevents movement of the stapes. This disease is a common cause of deafness in early adult life, especially in young women, but rarely occurs so early as to render the patient a deaf-mute.

The clinical examination of a case of suspected deaf-mutism is not easy. The observer has little or no means of communicat ing with the child. If the parents are both congenital deaf-mutes and the child is one of a family of deaf-mutes, there can of course be no difficulty in making a diagnosis; but the case is not often so clear as that. We have to seek the aid of knowledge derived from Mendelism before we can explain many of the spo radic cases of deaf-mutism. (See MENDELISM.) The history as obtained from the child's parents is often far from accurate, as they are unwilling to acknowledge, in congenital cases, that the child has never heard, and adduce such facts as that "the child notices a door slamming or a band passing in the street" as proof of hearing. The deaf-mute of course feels the vibrations caused by such disturbances. Further, the mother often states that the child can say "Mamma" and considers that this shows that it can hear, whereas an intelligent congenital deaf-mute may pick up such a word by watching its mother's lips. Even with regard to cases of acquired deaf-mutism the history of the case is often at fault, the deaf-mutism being attributed to "vaccination," or "fright," when subsequent enquiry and examination show that it has really been due to meningitis, or to the results of middle-ear disease. If the tympanic membranes show the effects of middle ear suppuration and if the deafness has only come on after the child has learnt to speak, one may be certain that the mutism has been acquired. In other cases where the deafness has only come on at the age of eight or nine years, examination may show that the upper central incisor teeth are peg-shaped and notched and that the cornea has become cloudy as the result of congenital syphilitic infection. Cases of acquired deaf-mutism due to menin gitis in infancy are hard to diagnose, but as a rule a clear history is obtained if the meningitis occurred in later childhood. These children are totally deaf. The rare cases which are caused by fracture of the base of the skull are also not difficult to diag nose.

Considerable help in the clinical diagnosis of deaf-mutism may be obtained from examining the semicircular canal apparatus or balancing portion of the ear. A normal child, if turned round rapidly in a rotating chair, becomes very giddy and shows twitch ing movements of the eyes (nystagmus). Cases of congenital deaf-mutism, in which the maldevelopment is confined to the hearing portion of the ear, react like normal children, but cases of acquired deaf-mutism due to destruction of the labyrinth from any of the causes described above almost invariably fail to become giddy on rotation. Another method of testing the balancing por tion of the inner ear is to syringe the ear with cold water. In a normal person such syringing produces giddiness and twitching movements of the eye and, if too prolonged, induces vomiting. Here again congenital cases react like normal children, while the acquired cases are not disturbed even by the most prolonged cold syringing. Nevertheless, it is not possible in every case to classify the child as a congenital or as an acquired deaf-mute.

The hearing power of children who are suspected of being deaf mutes may be tested in various ways, but it is impossible to be quite certain that a child has been born deaf before it reaches the age of one year. It is best to have the child seated on the knee of its mother or nurse and to attract its attention by show ing it some small object. (In some cases the question arises whether the absence of response to sound is due to deafness or to idiocy. The true deaf-mute child is generally mentally alert and at once takes notice of a coin or a watch shown to it.) An assist ant stands well behind the child and blows a whistle, sounds a rattle, or claps his hands, and the observer notes whether the child pays attention to the loud noise suddenly created behind it. The assistant must not stand too near, otherwise the child may feel the vibrations caused, for instance, by the clapping of hands. Kerr Love recommends a dinner bell to test the hearing of deaf children. The child is instructed to count the strokes. At a later age tuning-forks of varying pitch may be used to ascertain whether the child can hear them when vibrating close to but not touching the ear. Vowel sounds may also be spoken in a loud voice into the child's ear, but he must not be allowed to see the face of the examiner, as a good "lip-reader" may detect from the face or lips the particular vowel which is being used. Some deaf mutes have a fair amount of hearing which may be used for educational purposes ; indeed there are at the present time in deaf mute schools many children who should really be educated in special schools for the hard-of-hearing. Such schools, however, exist in but few centres in Great Britain. For education and training of deaf-mutes, see DEAF AND DUMB.