Sub-Order Ii Brachycera

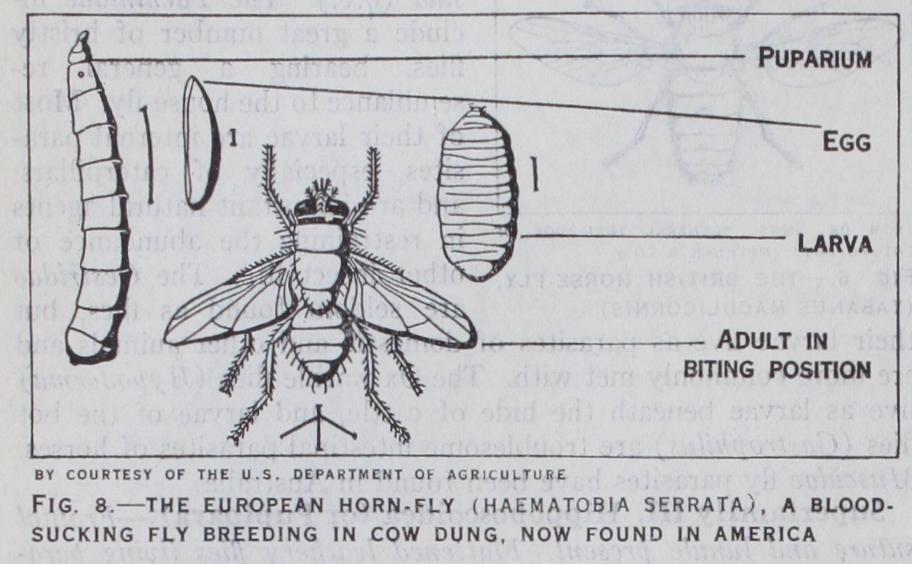

SUB-ORDER II. BRACHYCERA Mostly stoutly built flies whose antennae are three to six jointed and maxillary palpi one or two jointed. Wings usually with a median cell. Larvae gen erally with a much reduced head, (fig. 8) pupae free or enclosed in puparium.

This large sub-order is divisible into two series as follows: Series I. ORTHORRHAPHA.

Head without a frontal suture: antennae with a terminal bristle or prolongation (fig. 1). Larvae with a reduced Bead; pupae free and splitting by means of a dor sal fracture.

There are 14 families in this series, of which five are men tioned below.

The Stratiomyidae are more or less flattened flies usually with white, yellow or green markings, while some are metallic. The scutellum is often spiny and the last antennal joint is generally ringed. More than i,000 species are known and their larvae live in water or damp earth; the pupae are loosely enclosed in the last larval skin.

The Tabanidae (fig. 6) or horse-flies have a broad head, piercing mouth-parts and brilliantly coloured eyes. The costal vein is pro longed right round the wing and the halteres are hidden by a membranous scale or squama. The various species of Tabanus and the clegs (Haematopota) are troublesome blood-suckers, attack ing man, horses and cattle. Their larvae frequent damp earth and bear circlets of papillae around many of the segments. The family is widely distributed, none of the species is very small and over 2,0o0 kinds are known.

The Asilidae, or robber flies, are large insects with long, hairy bodies and elongate, bristly, prehensile legs. They prey upon other insects, extracting their body-fluids by means of their pierc ing mouth-parts. Their larvae live in soil and rotting wood.

The Empidae have similar habits but are not hairy and are less robustly built ; a tuft of hairs, forming a mouth-beard, present in Asilidae, is absent in this family. Both families are widely dis tributed and include many species.

The Bombyliidae, or bee-flies (fig. 7), are usually densely pubes cent and bee-like with a long projecting proboscis, slender stiff legs and often marbled wings. The flies suck nectar from flowers, and their larvae are chiefly parasitic upon those of solitary bees. Although only nine species occur in Britain, at least 2,000 kinds are known from various parts of the world. None of the above types are remarkable for brilliancy of colouring.

Series II. CYCLORRHAPHA. Head usually with a frontal suture with a small hard plate or lunule (fig. 2) above it: antennae with a dorsal bristle or arista (fig. I). Larvae with only a vestige of a head: pupae enclosed in the hardened larval skin or puparium (fig. 8) which ruptures by means of a circular fracture.

In these flies a kind of bladder (the ptilinum) is protruded through the frontal suture in order to force open the puparium, thus allowing the insect to emerge : the bladder is then withdrawn into the head.

Superfamily I. Syrphoidea.

Frontal suture rudimentary or absent: lunule present.Three families belong here, the most important being the Syrphidae, or hover flies, distinguished by the spurious vein, which crosses the wing without reaching the outer margin, and by the presence of an inner vein running parallel with the apical wing margin (fig. 9). Many of these flies are banded like wasps, while others are hairy and resemble bumble bees. The drone fly (Eris talis tenax) is a familiar example and, like most of the other species, hovers in the air with rapidly vibrating wings. The larvae exhibit diverse habits; many are predaceous upon aphids, etc., while others are scavengers in decaying matter or in the nests of bees and wasps.

Superfamily II. Muscoidea.

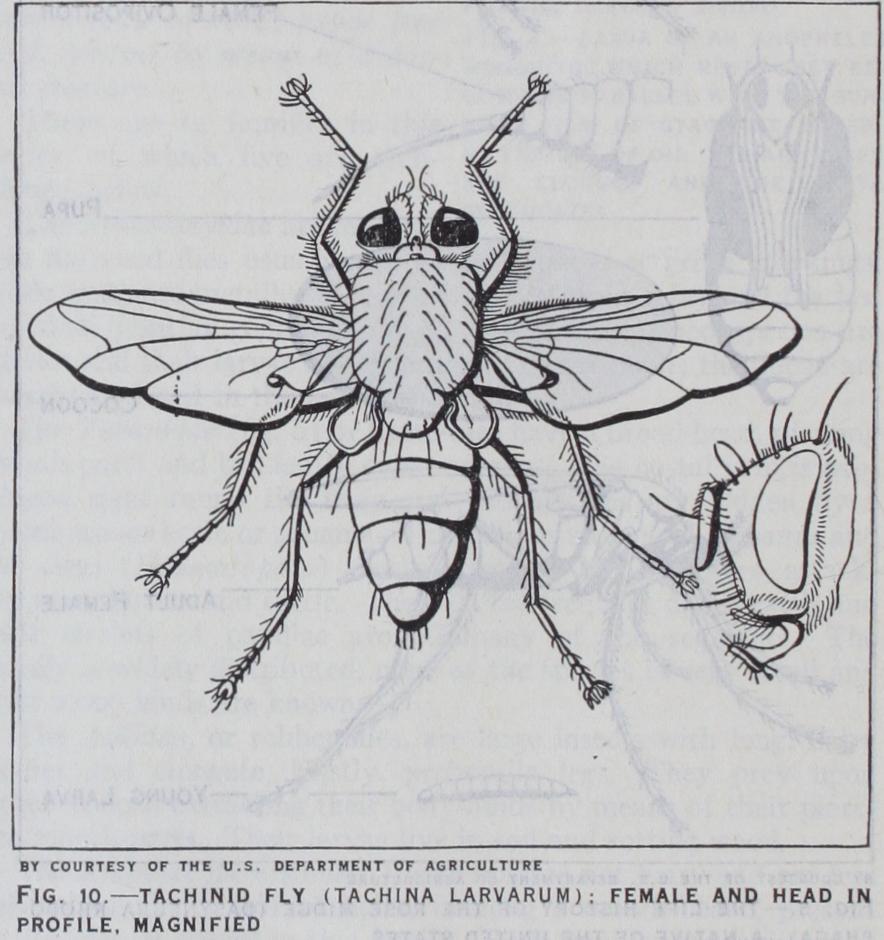

Frontal sutzlre and lunule present.This is an immense group containing many families, some of which are ill-defined and difficult to separate. The fruit-flies (fam. Trypaneidae) usually have prettily marked wings and their larvae attack various fruits, mine leaves (as in the celery fly) or form galls. The gout-fly of barley and the frit-fly of oats are well-known members of the family Oscinidae. The Agromyzidae include many flies whose larvae mine the leaves and other tissues of plants. The Muscidae are a very important family most of whose larvae are scavengers, or prey upon other fly larvae. known examples are the common house-fly, Musca domestica (q.v.), the blue-bottles phora) and the Tsetse flies, sina (q.v.). The Tachinidae clude a great number of bristly flies, bearing a general semblance to the house-fly. Most of their larvae are internal sites, especially of caterpillars, and are important natural agents in restraining the abundance of FIG. 6.-THE BRITISH HORSEFLY, other insect life. The Oestridae Fig. 6.-THE BRITISH HORSEFLY, other insect life. The Oestridae (TABANUS MACULICORNIS) are seldom found as flies, but their larvae live as parasites of domestic and other animals and are more commonly met with. The Ox warble flies (Hypoderma) live as larvae beneath the hide of cattle, and larvae of the bot flies (Gastrophilus) are troublesome intestinal parasites of horses. Muscidae fly parasites have been found in Australia.

Superfamily III. Hippoboscoidea (or Pupipara) . Frontal suture and lunule present. Flattened leathery flies living para sitically upon mammals and birds: the larvae are retained within the bodies of the females until about to pupate.

Three families belong here, the most important being the Hip poboscidae which include the forest-fly (Hippobosca equina) and its allies: the wingless sheep ked or tick (Melophagus ovinus) and the genus Ornithomyia, which infests birds, are also included. The families Nycteribiidae and Streblidae include highly aberrant insects found in many parts of the world living on bats. The members of the first-mentioned family are all wingless creatures of spider-like form.

Reproduction and Development.

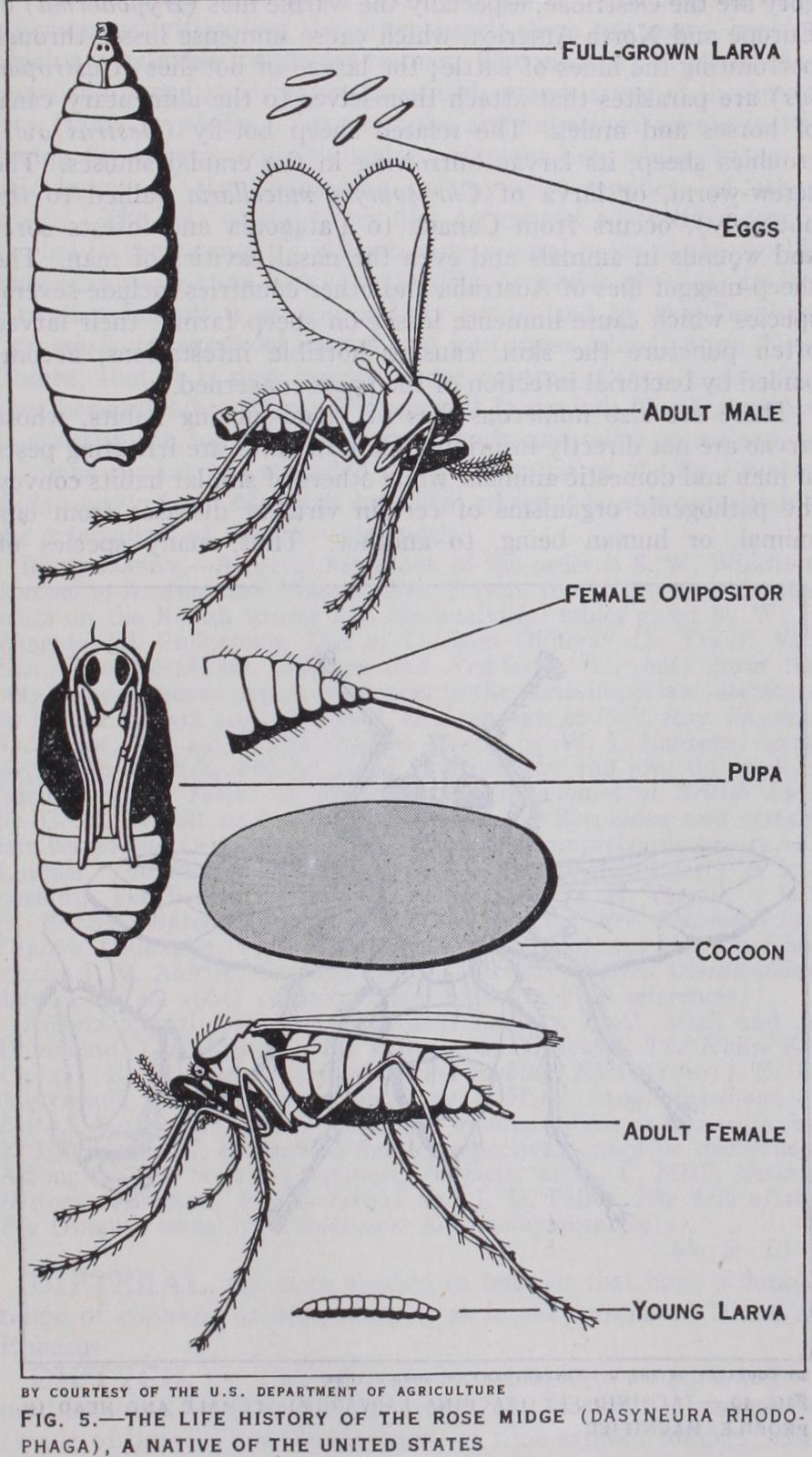

The eggs of flies are of diverse forms and are usually laid in large numbers : thus, a single house-fly in warm countries may deposit over 2,000 eggs during her life. By this insect they are deposited in masses of i 00–r 50, while by Culex mosquitoes they are laid in compact groups ing rafts which float on the surface of water. Many other flies deposit their eggs separately wherever there is sufficient food to nourish the larvae. Most flies pass through more than one generation in a season and in the presence of abundant larval food and a high ature, generation after tion may result. As a rule only a few days are spent in the egg, and in some flies the eggs are retained within the female until they have developed into larvae. In the Tsetse flies and the Hippoboscoidae the whole larval life is passed in this ner, and under such stances the larvae are nourished on a special secretion provided by the female fly. When fully grown, these larvae are "born" one at a time, at long intervals, and they quickly change into pupae. terous larvae never bear legs (fig. 8), they are commonly elongate and somewhat vermiform in shape, and only in certain families is the head fully formed. In most cases, they bear only an anterior and a posterior pair of spiracles, or the latter pair alone may be present. Owing to their legless condition, fly larvae pass a cealed life in the tissues of plants, burrowing in soil or in ing refuse and dung, in the bodies of insects or other animals, or in water. Perhaps the most remarkable life is that spent by an American fly whose larvae inhabit petroleum pools in California ; certain midge larvae occur in the sea and other dipterous larvae frequent hot springs. With this diversity of habitat there is found a wide range of food preference. Probably more fly larvae feed on decaying organic matter than on anything else; only in a comparatively small number of families do we find exclusively plant-feeders, but a considerable number of families have larvae that are predaceous or parasitic in habit. There are many struc tural adaptations which fit the larvae to their mode of life. Thus, most of the parasitic f orms have only a single pair of spiracles, situated at the caudal extremity. Such larvae bore a hole through their host's skin, and insert their tail-end therein in order to breathe the outer air. Some Tachinid larvae work their spiracular extremity into a main trachea of the host insect and breathe the contained air. Mosquito larvae have a similar disposition of the spiracles and keep their tail extremity above the water when taking in air. When about to pupate, fly larvae do not usually f orm cocoons, the pupae being protected by the medium in which the larvae lived. Among the more primitive groups of flies the pupae are free, but in the Cyclorrhapha the final larval skin persists around the pupa and hardens into a barrel-like puparium (fig. 8). Geographical Distribution.—It may be said briefly that all the important families of flies are very widely distributed but certain of the smaller groups are more restricted in their range. As a rule the largest and most striking members occur in the tropics where some of the most exaggerated developments of form are also found. Generally, however, the members of a given fam ily have a very constant facies, whether they come from the tropics or from temperate regions. The house-fly is practically cosmopolitan and is found wherever man has established himself ; many other flies such as Lucilia (green-bottles), Calliphora (blow flies) and Stomoxys (stable fly) have also become very widely distributed through human agencies, while some of the curious b a t - parasites (Nycteribiidae) have a wide distribution depen dent upon that of their hosts. On the other hand, the Tsetse flies (Glossina) are confined to Africa south of the Sahara, and the small family Acanthomeridae be longs to tropical America and the West Indies. Flies are also met with in very isolated situations.

The curious wingless crane-fly, Chionea, is found in Europe and North America on the surface of snow, while other wingless or semi-wingless Diptera are found on the shores of Kerguelen and other far-distant ocean islands.

Geological Distribution.

Diptera is one of the latest orders of insects to appear in geological time and is not met with until the Upper Lias of Europe, where certain Nematocera occur. There appears to be no certain evidence of the existence of the higher families until the Tertiary period. In Baltic amber and in the beds at Florissant, Colorado, numerous fossil flies occur.

Economic Importance.

No order of insects exceeds the Dip tera in economic importance. A large number of flies in their larval stages are destructive to cultivated plants. Among the most important of these is the frit fly (Oscinella frit) of Europe and North America, whicn is destructive to growing oats, while the closely allied gout fly (Chlorops taeniopus) produces swollen de formations of the ear-bearing shoots of barley. Leather-jackets, or larvae of certain crane-flies, cause much damage to the roots of cereals and other crops, while the cabbage root-fly (Chortophila brassicae) and the onion fly (Hyletnyia antiqua) entail losses to growers of those vegetables. The Hessian fly (Mayetiola destructor) is also a severe pest of cereals, both in Europe and North America. Mention must also be made of the Mediterranean fruit-fly (Ceratitis capitata) which attacks almost all kinds of succulent fruits in many tropical and warm regions, including south Europe.There are other flies whose larvae are injurious to man and domestic animals, and the affections induced by their presence are included under the general term of myiasis. Included in this cate gory are the Oestridae, especially the warble flies (Hypoderma) of Europe and North America, which cause immense losses through perforating the hides of cattle; the larvae of bot-flies (Gastrophi lus) are parasites that attach themselves to the alimentary canal of horses and mules. The related sheep bot-fly (Oestrus ovis) troubles sheep, its larvae burrowing in the cranial sinuses. The screw-worm, or larva of Chrysomyia macellaria (allied to the house-fly), occurs from Canada to Patagonia and infests sores and wounds in animals and even the nasal cavities of man. The sheep-maggot flies of Australia and other countries include several species which cause immense losses on sheep farms: their larvae often puncture the skin, causing horrible infestations, accom panied by bacterial infection of the parts concerned.

There are also numerous flies of blood-sucking habits, whose larvae are not directly injurious. Certain kinds are irritating pests of man and domestic animals, while others of similar habits convey the pathogenic organisms of certain virulent diseases from one animal, or human being, to another. Thus, many species of Anopheles mosquitoes are the direct carriers of malaria parasites from man to man. Yellow fever is only contracted when the mosquito Aedes aegypti (formerly known as Stegomyia fasciata) sucks the blood of man after having previously fed upon an in fected person (fig. 3). Another mosquito, Culex fatigans, is a carrier of the Maria worm which induces the disfiguring disease of elephantiasis, while the Tsetse fly (Glossina) is a carrier of the pathogenic organisms (Trypanosomes) of sleeping sickness in man and of nagana in domestic animals. The minute moth flies (fam. Psychodidae) include the blood-sucking genus Phleboto rnus, the members of which are small enough to pass through the meshes of mosquito curtains. Sand-fever or pappataci fever of Southern Europe, North Africa, etc., is transmitted from man to man by a member of this genus. Mention must also be made of the horse-flies (fam. Tabanidae) a species of which (Tabanus striatus) has been shown to transmit the pathogenic organism of surra among horses and other animals in the Orient.

The house-fly (Musca dornestica), although innocent of blood sucking habits, is a dangerous carrier of the germs of typhoid, infantile diarrhoea and other diseases. Being attracted to excre mentous matter, often containing disease germs, the insect's mouth-parts and body thus become contaminated and its faeces include ingested bacilli. Flies infected in this way readily con taminate food which consequently becomes a source of infection to human beings.

The economic importance of Diptera is not confined to their injurious activities: on the other hand, there are many species which are valuable auxiliaries to man. The majority of the preda ceous and parasitic forms are beneficial : many larvae of the hover flies (fam. Syrphidae), for example, are important agents in re ducing the excessive multiplication of plant lice, while the para sitic larvae of the Tachinidae destroy vast numbers of other insects. The role of the latter flies as natural controlling agents has led to their practical utilization in several parts of the world. Thus, the sugar cane borer beetle (Rhabocnemis obscura) in the Hawaiian Islands is so successfully parasitized by the Tachinid Ceromasia sphenophori, introduced into those islands from New Guinea, that it is now largely under control. Other Tachinidae have been introduced from Europe and Japan into North America to assist in the control of the gipsy moth, and quite recently con spicuous success has attended the importation of the fly Ptycho myia remote from Malaysia into Fiji, where it is now parasitizing the caterpillars of the coca-nut moth.

useful handbook of the order is S. W. Williston, Manual of N. American Diptera (New Haven, 1908). No general work exists on the British species and the analytical tables given by W. J. Wingate, "A Preliminary List of Durham Diptera" (in Trans. Nat. Hist. Soc. Northumb. Durham and Newcastle, ii., 1906) form the only comprehensive paper ; references to the more important literature on British Diptera are given by P. H. Grimshaw in Proc. Roy. Physical Soc. Edin., xx., 1917. The Diptera Danica by W. J. Lunbeck, being written in English, will be found of assistance, and also the various fascicles of the Faune de France; the two volumes of British Flies by G. H. Verrall deal exhaustively with the Syrphidae and certain families of the Orthorrhapha. As a modern comprehensive work, E. Lindner, Die Fliegen der Palaeartischen Region (Stuttgart) is im portant. The British species are catalogued by G. H. Verrall, A List of British Diptera (19oi), while the Katalog der Palaeartischen Diptera (Budapest, 1903-05) covers a wider field; for the American species J. M. Aldrich, Catalogue of N. American Diptera (Smithsonian Misc. Coll. 46, 1905) contains useful bibliographical references.

Among special works on individual subjects, L. C. Miall and A. Hammond, The Harlequin Fly (i9oo) ; C. G. Hewitt, The House Fly (1914) ; E. E. Austen, British Blood-sucking Flies (ioo6) ; E. E. Austen and E. Hegh, Tsetse Flies (1922) ; Ii. C. Lang, Handbook of British Mosquitoes (192o) ; and two volumes, Flies and Disease, by E. Hindle and G. S. Graham-Smith, respectively, may be mentioned. Among the few books of a popular character are L. C. MialI, Natural History of Aquatic Insects (1902) and J. H. Fabre, The Life of the Fly (English trans. from Souvenirs Entomologiques (1913) .

(,A. D. I.)