The Design of Docks

THE DESIGN OF DOCKS Docks require to be so designed that they may provide the maximum length of quays in proportion to the water area con sistent with easy access for vessels to the quays. Often, however, the space available does not admit of the adoption of the best forms, and the design has to be made as suitable as practicable under the existing conditions.

Planning.

On this account, and owing to the small size of vessels in former times, the docks of old ports present a great variety in size and arrangement, being for the most part narrow and small, forming a sort of string of docks communicating with one another, and provided with locks or entrances at suitable points for their common use. Such conditions are noticeable in the older London and Liverpool docks.Where the conditions of site permit, the ideal plan for a com mercial dock comprises an ample vestibule or turning basin and a series of wide parallel piers or quays with intervening water spaces or branch docks arranged like the teeth of a comb, but inclined slightly towards the approach channel. Vestibule planning has been embodied in the lay-out of many large modern docks including those of Manchester, Dunkirk, Hull and the open basins at Glasgow. It is also the characteristic feature of modern ports in tideless seas enclosed by protection works as at Marseilles.

Liverpool.

The later Liverpool docks at the northern end of the series, including the Gladstone dock (Plate II., fig. 5) have been constructed on the vestibule plan with branches. Sotne of the older docks adjoining them to the south have been remodelled so as to form series of branch docks opening into vestibule docks alongside the river wall. The Gladstone dock includes a vestibule or turning dock, a graving dock, also usable as a wet dock, two branch docks and a large deep water lock giving access from the river. The water area is 58+ acres and the quayage about 3m. in length. A lock between the adjoining Hornby dock and the new dock makes it possible for ships to enter and leave some of the older docks by way of the deep river lock.

Port of London.

Though narrow timber jetties were intro duced long ago in some of the wider London docks for increasing the quay space, no definite planning arrangement was adopted in building the large Victoria and Albert docks between 185o and 1880. The Victoria dock was made wide, with solid jetties pro vided with warehouses projecting from the northern quay wall, thereby affording accommodation for vessels lying end on to the north quay. The Albert dock, which was subsequently con structed, was given about half the width of the earlier dock, but made much longer, so that vessels lie alongside the north and south quays in a long line. This change of form, however, was probably dictated by the advantage of stretching across the re mainder of the wide river bend, in order to obtain a second entrance in a lower reach of the river.The Tilbury docks (1886) (Plate II., fig. 1), consist of a series of branch docks separated by wide, solid quays, and opening straight into a vestibule dock in which vessels can turn on enter ing or leaving. An extension of the main dock at its western end to form a larger branch dock was made in 191 2-1 7, adding about 17 acres to the previously existing 54,1 acres of dock water area. (See Proc. Inst. C.E., 1923.) A further enlargement was begun in 1926 which will provide an additional entrance higher up the river, and a water area sufficient for turning the largest ships.

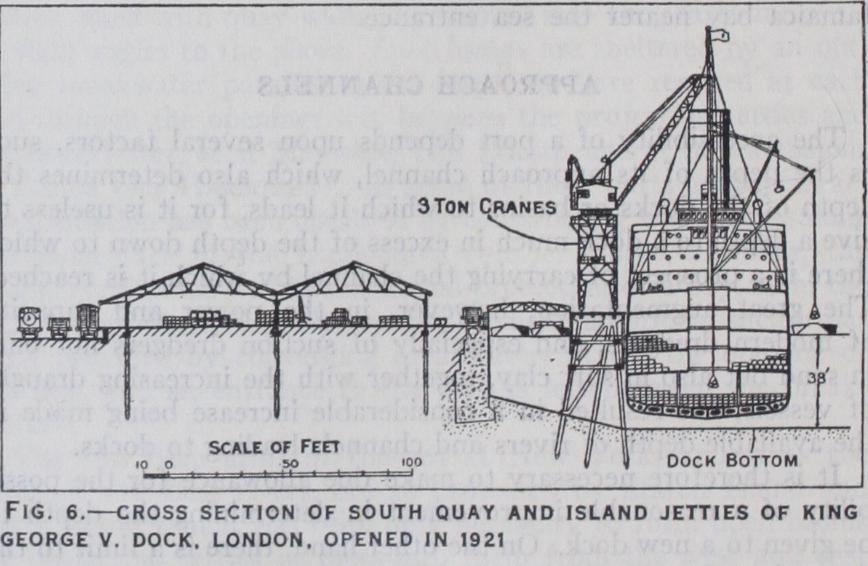

The latest of the docks in the port of London, the King George V. dock opened in 1921 (see Proc. Inst. C.E., ccxvi., 1923) occu pies a site lying between the river and the Royal Albert dock with which it is connected by a communication passage. It has a separate entrance from the river by means of a deep lock. The wet dock has an area of about 64 acres and is constructed on the single water-area plan without branches. The two long quays which form its sides are not parallel, the width between them at the entrance end being sufficient to allow of ships turning. An interesting feature of the design is the provision of 7 reinforced concrete island jetties arranged in a line parallel with the south quay-wall with a barge passage between the jetties and the quay (fig. 6) . Cranes on the jetties work the ship's cargo either into barges or to the quay as may be required. This system was intro duced with the object of affording better facilities for lighter borne traffic which forms a large proportion of the trade of the port of London.

Tidal and Half-tide Basins.

Tidal basins, as they are termed, were interposed in many old docks between the entrance locks or tidal gates and the dock proper, with the object of facilitating the passage of vessels out of and into the docks before and after high water. This is effected by lowering the water in the basin to meet the rising tide and opening the outer gates directly a level has been formed. The outgoing vessels which have collected in the basin, when level with the dock water, are then passed successively through the outer gates. The incoming vessels are next brought into the basin, the outer gates are closed, and the water in the basin raised to the level in the dock, when the vessels are admitted to the latter. This arrangement, which in effect serves the purpose of a large lock, is still in use at a few of the older docks in the Port of London and also at the Bute and Roath docks at Cardiff, and at Sunderland and other docks. The locks, where they exist, are used (as locks) only for the smaller vessels leaving early or coming in late on the tide.The large half-tide locks at many of the Liverpool docks serve a similar purpose as tidal basins, but, being much larger, the gates are closed at high water to prevent the lowering of the water level in the dock, and to avoid closing them against a strong issuing current. All entrances on the Mersey have duplicate pairs of gates in case of any accident occurring to one pair. This practice has been followed at some other ports.

The so-called tidal basins outside the locks at Tilbury and Barry (see Proc. Inst. C.E., ci., 189o) are open water spaces provided to give a sheltered approach to the lock or entrance with comparatively deep water available at or near low water for vessels waiting to enter.

Dock Entrance Channels and Locks.

The more modern practice in planning the approach to a large wet dock is to form a funnel-shaped channel between entrance jetties at the head of which is situated a large entrance lock usually capable of division into two parts by intermediate gates. This plan has been adopted at the King George V. dock in the river Thames ; the Gladstone dock, Liverpool; and for the modern entrances at Newport, Cardiff, Avonmouth, Immingham and other docks. The new en trance at the Tilbury docks will also be of this type. When large lock entrances are constructed in a river whose current is at times swift it is now the practice to align the lock and entrance channel at a small angle with the direction of the current, and not at right angles to the river, in order to avoid the necessity of large ships getting athwart the tide in entering or leaving the dock. The latest Liverpool, Tilbury and Antwerp entrances are planned in this way.

Emergency Entrances.

It is desirable, although not always practicable for financial and other reasons, that a wet dock should be provided with some alternative access besides that which is in ordinary use. If there be no such provision a serious accident to the one lock or entrance might close it to traffic for a time and prevent ships already in the dock leaving it. In most of the Liverpool and London docks this risk is met by the con struction of communication passages between adjoining docks, so that, in the event of any lock or basin entrance being out of operation, some alternative entrance in another dock can be uti lized. Moreover, in busy and important docks, the building of an alternative entrance is often necessary for traffic reasons if delay to ships entering and leaving is to be avoided. It may be noted that the plans for the Gladstone wet dock provide for the future building of an entrance alongside the deep lock, and of the same width (fig. 4).At Havre and many other ports, a pair of gates in a tidal entrance alongside the main lock allows ships to enter and leave at high water if the lock is not working. At Barry dock, the basin entrance is available if the lock cannot be used ; and at Rosyth dockyard an emergency entrance closed by a sliding caisson, is built alongside the entrance lock. (See Proc. Inst., C. E. vol. 223, 1927.) Dimensions of Dock Entrances and Locks.—The size of vessels which a port can admit depends upon the depth and width of the entrance to the docks; for, though the access of vessels is also governed by the depth of the approach channel, this channel is often capable of being further deepened by dredging. The solid structures of the dock entrance, on the other hand, cannot be adapted to the increasing dimensions of vessels except by trouble some and costly works sometimes amounting to reconstruction as carried out at some of the London docks.

The width and depth of access to wet docks are in one way of more importance than the length of locks: for gate entrances, and also locks if both pairs of gates are opened at high water, impose no limitation as regards length on ships entering or leav ing. (The terms "entrance" and "gate entrance," used without qualification in connection with a wet dock, commonly imply an entrance closed by a single pair of gates or by a caisson as distinct from a lock.) This factor is of importance in the working of some old docks whose locks are of limited length but of ample width. It is, however, usual in modern dock construction to make a lock amply long enough for any ship whose beam or draught is not too large for the limiting dimensions of its entrance.

Open basins are generally given an ample width of entrance and river quays are also always accessible to the longest and broadest ships which can navigate the channel leading to them. In a tidal port or river, however, the available depth in the berths has to be reckoned from the lowest low water of spring tides, instead of from the lowest high water of neap tides, if the vessels in the open basins and alongside river quays have to be always afloat.

Many years ago the Canada lock (185 7) at Liverpool, the Alfred lock at Birkenhead, the Ramsden lock and entrance at Barrow-in-Furness, and the Eure entrance at Havre, were all given a width of about Ioo ft. This was no doubt done with the view of admitting the paddle steamers of large overall width in use at the time. With these exceptions the-widest lock entrance in the world, until the beginning of the present century, was at the Alexandra dock, Hull, opened in 1885, which was made 85ft., the length being 5 5of t. The wide entrances to the deepened Brunswick dock and the Sandon dock at Liverpool, completed in 1906, were made roof t. wide, with sills more than Soft. below high water of low neap tides. The Gladstone graving dock, which is also usable as a wet dock, opened in 1913, has an entrance 120 ft. in width. The latest addition to the Liverpool docks, the Gladstone wet dock, has a lock Io7oXI3oft. internally.

The depths of the sills of locks and entrances at large ports have increased in much the same ratio as their other dimensions. Thus, in the port of London, the old lock of the Albert dock, opened in 188o, has a depth of 261ft. at high water of neap tides and I oft. at low water of spring tides: the Tilbury lock (1886 ) has corresponding depths of 391 and 23 -ft. over the outer and intermediate sills, but 6ft. less over the inner sill. All the sills of the King George V. lock are and those of the new Tilbury lock will be 4I ft. below the level of high water neap tides. The following table shows the dimensions of some of the largest locks in use or building in 1928 : *At levels of H.W.N.T.

iCan be increased to 9ioft. if necessary by use of caisson at the inner end.

The only other locks in the world having usable dimensions of i,000X ooft. or more are those of the Panama and Kiel canals (see CANALS) the former are I,000X I 'oft. and the latter i,o83X147-ift.

Open Wharves and Quays.

Where the range of tide is moderate, closed docks, if they exist, or open basins are usefully supplemented by quays or wharves in the river or harbour in positions where the shelter is sufficient for vessels to lie along side in safety and the currents are not too strong to make this impracticable. Generally a range of 14 or i5ft. at spring tides is the limit above which it becomes more convenient to provide closed docks. On the river Tyne, where the range is I41ft., the open water quays and coal staiths about equal the closed dock ac commodation in extent. On the Clyde, with a tidal range of from io to i3ft., and at Hamburg (fig. 7), with a range of 7ft., there are no closed wet docks. At Antwerp, a port possessing a very large closed dock system, and having a tidal rise of 15ft., a long line of quays has been constructed along the right bank of the Scheldt at which large ocean-going ships are berthed. Even in the Thames, with a spring range of 2I ft., deep water jetties and wharves have been built in the river.On the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of North America, where the tidal range, except in the Bay of Fundy, is generally small and most of the larger ports are in situations possessing ample natural protection, accommodation is provided for shipping at long piers or jetties projecting from the shore into deep water. Many of these piers, or "docks" as they are termed in New York, have berths upwards of i,000ft. in length with 3o to 45ft. depth at low water. Timber and reinforced concrete piles are commonly em ployed for these. structures, but sometimes cylinders are used in place of piles for carrying the superstructure of the jetty. The same type of construction has become usual in the natural harbours of Australia and New Zealand where, except in the northern parts of Australia, the tidal range is also small.

The following table (II.) gives particulars of the depth at low water alongside typical deep water tidal quays built since 191o.

water in a wet dock, in view of the greater draught of the vessels using it, as an alternative to the deepening of the dock which may be inadvisable on constructional or economical grounds. This has been effected in several cases by installing centrifugal pumps which maintain the water level in the dock at a high level by pumping from the tideway about the time of high water. Since t 9o9, when the Port of London Authority was constituted, pumps have been installed at many of the London docks to maintain the dock water at levels i to 3+ft. above T.H.W. (Trinity High Water, which is 1.5ft. below the level of mean high water spring tides at London Bridge, and z 2.5ft. above Ordnance Datum.) In the absence of pumping the water levels would fall at neap tides con siderably below T.H.W. At the Queen Alexandra dock, Cardiff, at the Newport docks, and at many of the Liverpool docks the water levels are maintained, by pump ing, at or about the level of high water of spring tides. The British Admiralty prac tice is to utilize the pumping plant, which is installed for unwatering dry docks, for raising water levels of wet docks when necessary.