The Distribution of Terrestrial Animals

THE DISTRIBUTION OF TERRESTRIAL ANIMALS The environmental conditions which influence the distribution of terrestrial animals are much more complicated than those brought to bear on aquatic animals. The chemical composition of the air is not important, as complete intermixture can take place very quickly. Only in a few places where carbon dioxide is present does this accumulate in limited areas, by reason of its weight, and render them uninhabitable by animals, as in the Grotto del Cane, at Pozzuoli. More important is the physical condition of the at mosphere, that combination of conditions called climate, and which is not present in water in such complexity. Such climatic factors are atmospheric moisture, temperature, atmospheric move ments and solar radiation, some of which change periodically.

Moisture.

The amount of atmospheric moisture varies with time and place. Where the air is saturated, as in tropical rain forests, even soft-skinned animals (planarians, leeches) can live out of water without danger of drying up. In such places a rich fauna and flora is found. Life is scarcest in regions where atmos pheric moisture periodically fails completely, as in desert regions far from the sea. There are animals, however, which can live in a moderately dry atmosphere, as they can limit their evapora tion of water as required. Air-breathing animals may be divided into moist-air breathers and dry-air breathers. To the former belong snails, many insects, such as ephemerids and mosquitos, all amphibians, buffaloes, hippopotami and some South American monkeys. These are characterized by the possession of numerous skin glands, liquid urine and watery excrement. Dry-air breathers include most insects, reptiles and birds ; they have no skin glands, and excrete uric acid ; among mammals, many rodents, some ante lopes, roe-deer and camels; these have few skin glands, dry excre ment and concentrated urine.

Temperature.

Although the quantity of atmospheric mois ture in many ways influences the distribution of air-breathing animals, the effects of temperature are still greater. The tempera ture of air varies to a much greater degree than that of water, and does so more rapidly and more extensively. Whilst in water the lower limit of temperature is o° C (+32° F), in air it may sink to — 67.8° C (-8o° F) (at Werchojansk) ; on the other hand, it may, in instances, rise to 56.6° C (ioi.7° F). The greatest differ ence between the highest and lowest mean monthly temperatures in any place is at Werchojansk, where it amounts to 66.3° C daily variations at 2 2° C occur in elevated steppes.The distribution of animals, therefore, is determined by the degree of warmth they require. Animals limited to a uniformly high temperature, i.e., warm-stenothermal animals, in temperate regions live only in particularly warm localities, especially on chalk soil. As examples may be mentioned the green lizard (La certa viridis), and the praying mantis (Mantis religiosa), when found north of the Alps. Cold-stenothermal animals, on the other hand, inhabit places with a lower temperature; e.g., snails of the genus Vitrina are found on the summits of the Alps, on Mt. Kilimanjaro and in the Cameroons, but are absent in warm parts.

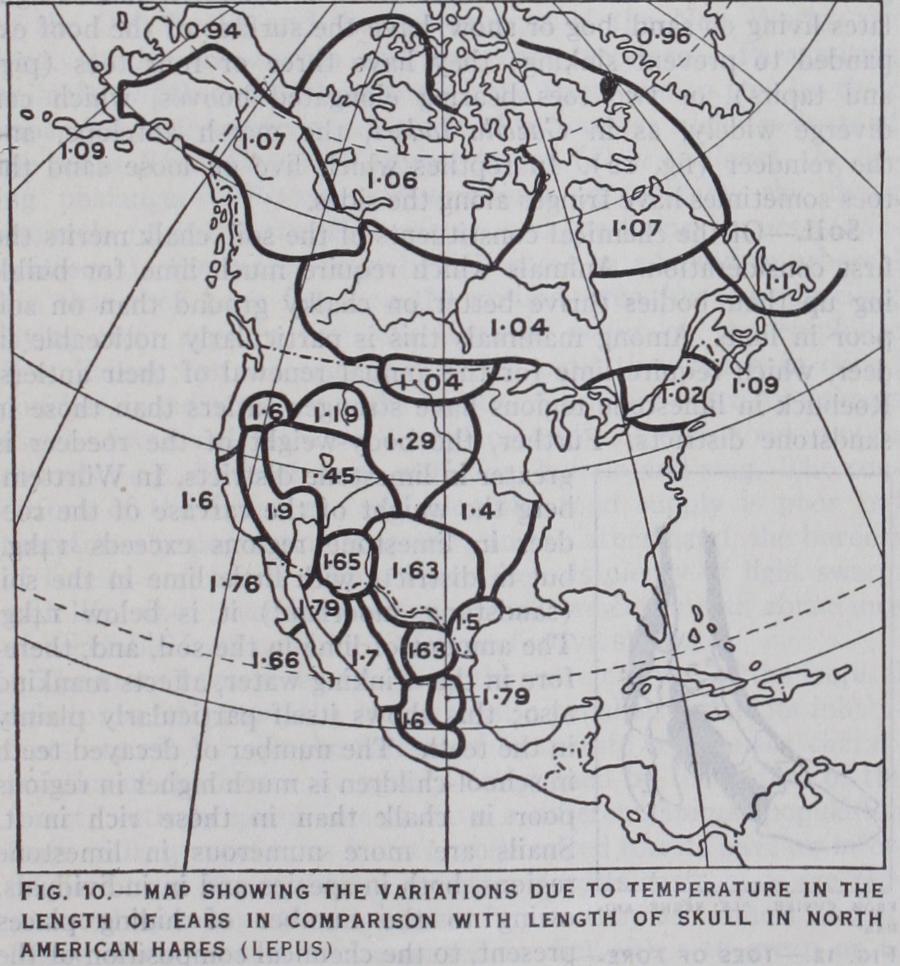

Homoiothermal (warm-blooded) animals are not immediately influenced by their surrounding temperature. The temperature of the surroundings, however, by its. variations renders difficult the regulation of internal heat. The problem of the limitation of the amount of heat given off is solved in various ways. Thick cover ings of hair or feathers, or the deposition of fat beneath the skin are the most important ; in many birds air-sacs assist in maintain ing a protective warmth round the internal organs. It is impor tant, also, that the surface-area of the body, where heat radiation takes place, should be lessened. Birds, as compared with mam mals, have a very small surface in proportion to mass. Among mammals the external ear and the tail are parts where much heat is given off, and for this reason they are smaller in animals dwell ing in cold regions than in their relatives in warmer parts. For instance, the ears of the Arctic fox are small, those of the Euro pean fox are larger and those of the desert fox largest (fig. 9). The length of the ears in comparison with that of the skull in North American hares (Lepus), is shown in fig. 1o.

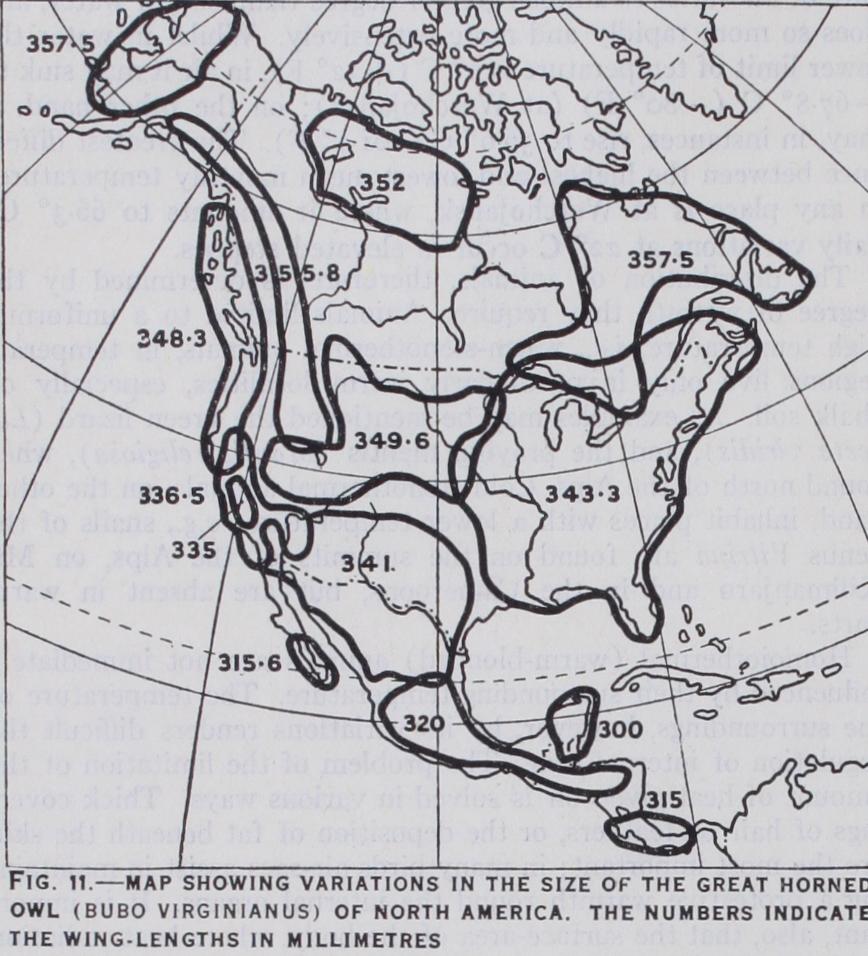

Since large animals have a relatively smaller surface-area than small ones, this implies in them a diminution of the giving-off of heat. Of two dogs weighing 2okg. and 3.2kg., having surface areas of 7,5oo and 2,423 sq.cm. respectively, the larger had a surface-area of 375 sq.cm. per kg. of body-weight, the smaller 757 sq.cm., i.e., about double the area ; the larger produced in unit of time from kg. of mass 45 calories, the smaller 88 calo ries; the amount of heat given off, therefore, rises in proportion to the surface-area. It is worthy of note that warm-blooded ani mals in cool regions usually attain a larger size than the corre sponding species in warmer climates (Bergmann's rule). Fig. Ir shows the increase in size, corresponding to decrease in tempera ture, in the Great Horned or American eagle owl. The coldest parts of a faunal region are therefore centres of maximal forms, while the warmest parts are centres of minimal forms. In the Palaearc tic region warm-blooded species have a minimum size on the south coast of the Mediterranean, while in northern Siberia they reach their maximum size. In North America Alaska is a centre of maximum size, for example :—among mammals the bear (Ursus gyas), the fox and the moose (Alce gigas); among birds, the eagle owl (Bubo virginianus), the Alpine lark (Otocoris alpestris) and the pine grosbeak (Pinicola enucleator), all being larger than normal. Smaller forms are in Florida and Lower California.

Peculiarities of Tropical Fauna.

A uniform climate is found chiefly in some tropical regions of America, Africa and India, particularly in tropical forest areas. These are distin guished by the absence of seasonal changes, and by offering opti mum conditions of moisture, warmth and light. The abundant vegetation permits rich development of animal life. Poikilother mal animals enjoy almost the same favourable conditions as have been established internally as the optimum in homoiothermal ani mals. Homoiothermal animals require considerably less food than in temperate regions. Many classes of animals attain a consid erable size in the tropics, e.g., numerous insects, millipedes, spi ders, snails. Here amphibians and reptiles attain maximum size.

Brilliant colours and clearly defined markings are characteristic of tropical animals. The number of living organisms is enormous. Development takes place quickly, generation following generation in rapid succession. The butterfly Danaus chrysippus in the north ern parts of its area of distribution is represented by one genera tion a year, but in the Philippines it requires only 23 days for complete development. Among mammals also development is accelerated, as puberty is reached much sooner (in the 12th year in man). The number of species is astonishing. South America has 4,56o species of Lepidoptera, while the whole of the Palaearctic region (Asia north of the Himalayas, Europe and north Africa) has only 716. The Brazilian states of Para and Amazonas have 1,117 species of birds, i.e., almost as many as the whole Palaearctic region (1,218). The number of individuals of a single species, however, is usually limited; of insects and spiders it is often easier to collect 10o different species than 10o individuals of one species. The absence of seasons causes reproduction to go on during the whole year; one may find at any time of the year eggs, larvae, pupae and fully developed animals.

Temperate Regions.

On the other hand, in regions where periodical changes of temperature give rise to seasons, animals are subjected to conditions varying from times of plenty to times of need. It is immaterial whether the changes be between summer and winter, or between rainy season and dry. Summer and the rainy season bring the most favourable conditions, winter and drought the least favourable. Animal life languisl3es under unfa vourable conditions, lack of warmth in one place bringing about a state similar to lack of moisture in another. When, however, the bonds are loosed, the awakening of the animal world is the more effectual owing to the simultaneous appearance of many species. Most species immediately set about reproduction ; the chirping of crickets, the croaking of frogs, and particularly the songs of birds, together with the awakening of plant-life, is in sharp, refreshing contrast to the desolation of winter and the dry season. In winter, or the dry season, many terrestrial animals cease their vital activities. Aestivation in time of drought is com mon among insects, spiders and snails; frogs and toads creep into holes in the earth or other hiding-places, and remain there in a death-like sleep. Crocodiles dig themselves into the mud of pools which are drying up, and rest beneath the hardened crust. This habit of sleeping through the dry season is also found among mam mals; e.g., the aardvark (Orycteropus) in Africa. In winter, poikilothermal animals hibernate in a similar way ; this may also occur in warm-blooded animals, which undergo a drastic fall of temperature and a slowing-down of the rate of metabolism. Such are hedgehogs, bats, dormice and marmots. Among birds, how ever, we find neither hibernation nor aestivation; they withdraw from the reach of unfavourable seasons by migrating. Migration (q.v.) occurs also among mammals, brought about by seasonal changes of weather. It occurs among South African antelopes, reindeer and bats. Among birds of temperate regions, we may distinguish a general resident population, which dwells the whole year in the same locality; migratory birds present only for the breeding season (summer visitors) or only in the non-breeding season (winter visitors) or occurring on passage between their summer and winter habitats. According to the climate of the habitat the same species may be resident in one locality and mi gratory in another. Thus in England birds such as starlings and song-thrushes remain throughout the winter; in central Europe they migrate. Some birds travel great distances; the summer and winter quarters of Sterna paradisea are 17,7ookm. apart. The change from rainy season to dry causes migration, as in Africa.The nature of the soil of a locality is important in determining the composition of its population, particularly as regards the higher forms of life. Among mammals the two-legged jumping animals require a hard substratum, which offers a firm foothold. These are found in all the steppe regions of the earth. Such are jerboas, the jumping hare pedetes, and the kangaroo group of mar supials. Running animals, such as carnivores which go upon their toes, and ungulates, which place only the tips of the toes on the ground, favour a hard soil, where there is least friction. Ungu lates living on sand, bog or snow, have the surface of the hoof ex panded to prevent sinking; they have three or four toes (pigs and tapirs), or two toes bearing elongated hooves, which can diverge widely, as in Gazella loderi, the marsh antelope, and the reindeer (fig. 12) . In reptiles which live on loose sand the toes sometimes have fringes along the sides.

Soil.

.Of the chemical constituents of the soil, chalk merits the first consideration. Animals which require much lime for build ing up their bodies thrive better on chalky ground than on soil poor in lime. Among mammals this is particularly noticeable in deer, which require lime for the annual renewal of their antlers.Roebuck in limestone regions have stronger antlers than those in sandstone districts. Further, the body-weight of the roedeer is greater in limestone districts. In Wurttem berg the weight of the carcase of the roe deer in limestone regions exceeds 14kg., but in districts with little lime in the soil (sandstone, moorland) it is below 14kg. The amount of lime in the soil, and, there fore in the drinking water, affects mankind also; this shows itself particularly plainly in the teeth. The number of decayed teeth in school-children is much higher in regions poor in chalk than in those rich in it. Snails are more numerous in limestone regions, both in species and in individuals, owing to the number of hiding places present, to the chemical composition of the soil and to the warmth of the chalk.

Other animals require a large amount of salt in the soil, and are widely distributed on sea-coasts; inland, they are found only on salt ground, as at Stassfurt and in similar localities. This applies particularly to the small beetles (Staphylin idae, Carabidae) and other insects. Salt is sought after by mam mals also, particularly by herbivores; places where it crops up are much resorted to by ruminants, and in primaeval forests they have paths converging to them from all directions.

The Fauna of Forests.

Large forests are found only in re gions where, during the four months vegetative season, a minimum temperature of r o° C prevails, a minimum rainfall of Socm. and an atmospheric humidity of more than So% saturation. The dense covering of the tree-tops hinders penetration of heat-rays, evaporation of moisture and air-currents. For this reason, tem perature, humidity and air-currents vary much less than in open country. The density of forests, moreover, varies greatly ; all grades are found from the tall, hot, impenetrable, dripping rain forests of the tropics, to the light pine forests near the tree limit on mountain slopes and in the sub-arctic region. The peculiarities of forest animals are seen most plainly in the tropical rain-f orests, which form an immense zone round the earth at the equator, and include the Congo forest region, the forests of southern Asia and the islands of that region and the selvas of the Amazon.Orientation is possible only for short distances, eyes and organs of smell are not much use ; the sense of hearing is the most useful. The gregarious forest animals, therefore, such as birds and mon keys, are noisy, in contrast to those of open country. The light is subdued and much reflected ; brilliant colours do not show up; protective coloration is rendered unnecessary by the restriction of the outlook. Flying and running are hampered ; the true forest birds are usually poor fliers, but are good at gliding and climbing. Some forest animals, such as elephants and large swine, are able to force their way through ; others are small and slender, stand lower in front than behind, carry the head low, and are able to squeeze through narrow places, e.g., forest antelopes (Cephalolo phus, Tragelaphus), forest deer (muntjac) and agutis (Dasy procta). Many birds and mammals are equipped with sharp claws (woodpeckers, squirrels, martens) ; others have gripping-feet (par rots, monkeys, arboreal marsupials), some have prehensile tails (many South American monkeys, the porcupine Erethizon, the anteater, various marsupials).

Climbing animals in forest regions include also many reptiles and amphibians, such as the laterally-compressed tree Agamidae of the Old World, and the tree-iguanas of the New World, the long, slender tree-snakes and numerous tree-frogs. Parachuting animals, which can prolong their leaps from tree to tree by their expanded under-surface, are confined to forests ; such are frogs of the genus Rhacophorus, the flying dragon (Draco volans), the fly ing phalangers (Petaurus, Petauroides, Acrobates), the flying squirrels (Anomalurus, Petaurista), and the flying lemurs (Gale opithecus). Some tree-frogs have become so adapted to arboreal life that they have forsaken the ground even for reproduction; laying their eggs in the collections of water on the epiphytic Bromliaceae ; or the eggs are carried until they hatch in dorsal pouches, in gular sacs or in the mouth. A number of active animals use the forest only as a dwelling place, and seek their food in open country; e.g., birds of prey, wolf, fox, buffalo and stag. The con ditions of the forest are uniform ; the food supply is poor and therefore the population is sparse; on the other hand, the borders of forests and forest glades where there is plenty of light swarm with life, since there is room for free movement and an abundance of vegetable food combined with protective shelter.

The more a forest departs from the extreme type of the tropical rain-forest, the more the characteristic peculiarities of its inhabi tants are effaced. In the forests of temperate regions the charac teristics of the fauna are mostly determined by the nature of the forest; entirely green forests have a different animal population from entirely coniferous forests, while mixed forests have an inter mediate type of population. In green forests gastropods are rep resented by many species, in pine forests they are almost absent. Many forest insects are restricted in diet either to green or to coniferous trees. Green forests are preferred by the black grouse (Tetrao tetrix), the pheasant, song-thrush, blackbird and white throat ; and by the dormouse (Muscardinus avellanarius) among mammals. Coniferous forests are preferred by the capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus), great black woodpecker (Picus martins), nut cracker (Nucifraga), crossbill (Loxia), siskin (Carduelis spinus) and gold-crest (Regulus).

Fauna of Open Country.

Open country is in every respect in contrast to forest regions. Forests are not found where moisture and warmth are insufficient ; in such places only grass and shrubs are present. Such lack of moisture is often found in great plains, both elevated and low-lying. But there are numerous grades of open country, from savannahs and steppes to pre-desert (shrub steppe), and desert. The gradations depend on the degree of pre cipitation; this is greatest in subxerophilous grasslands; in arid steppes it is confined to the rainy season, and in waterless deserts it may be absent for years. In the rainy season, such regions show very diverse appearances, but in the dry season they are much more alike. All have an absence of protective foliage, and, on this account, variations of temperature and humidity are great, and atmospheric currents are strong.In general only animals which can endure a dry atmosphere are able to exist in open country ; those requiring moisture in the air, such as gastropods and amphibians, are rare. An extraordinary number of animals seek shelter in holes and burrows in the ground from storms, enemies and variations of temperature. Here we find ants and other brood-nursing Hymenoptera, and termites. Among burrowing reptiles are the Caspian tortoise (Clernmys caspica), skunks and many snakes (Typhlopidae, Eryx, Psammophis). Among mammals, rodents show the greatest number of burrowing forms, such as the marmots (Marmotta), prairie-dogs (Cynornys), sousliks (Spermophilus), rats, voles, hamsters (Cricetus), jer boas, porcupines, the South American Hystricomorpha (Ctenoynys, Dolicliotis, Viscacia), and rabbits (Lepus cuniculus); they often live in large communities, and undermine extensive areas. Arma dillos (Dasypus), ant-bears (Orycteropus), wart-hogs (Phaco clioerus), and predatory animals (e.g., Canis cerdo in Africa) dig holes for themselves in open country. The birds are ground-breed ing forms, but others such as eagles, which usually nest in trees, occasionally breed on the ground in such regions. Others again make their nests in the holes of rodents, e.g., the burrowing owl (Speotyto). In such regions, where there is little cover, the col ouration of the animals is frequently adapted to that of the sur roundings; the less cover present, the greater the degree of adap tation. This is found to the greatest degree in deserts, where the most varied kinds of animals have coloration similar to that of the ground (Plate II.) . A few insects which have special protection in their hard cuticle (some Tenebrionidae), or which eject a poi sonous fluid against attackers (the locust Eugaster guyoni), have a striking black colouration.

Agile animals are particularly characteristic of open country. Here are found running birds such as the ostrich, partridge, desert jay (Podoces) and larks. The solipeds and two-legged jumping animals are inhabitants of open country. Visual and olfactory organs assist orientation, as the outlook is wide and the winds carry scents. Animals of open country, in contrast to those of forests, make little noise. Gregarious animals are particularly common. The subxerophilous grasslands are the richest game regions of the world ; the North American prairies formerly har boured enormous herds of bison; the South African plains swarm with herds of ungulates.

Plains where winter is the dry season and those covered with snow at this season differ in several respects. In the dry season the former offer food in dry grass and its seeds, which keeps life from dying out. In regions where the grass in winter is covered by snow, vegetation decays and is useless as food ; all animals hibernate or migrate. When the dry season is past and the first rains begin, life awakens suddenly, but where there is snow, plants and animals awaken gradually at the end of the winter. All these peculiarities are most marked in desert regions with their extreme conditions of life; the scarcity of animal life and the sharp com petition, the frequency of protective coloration, the paler colora tion of the animals, are all direct effects of climate.

Fauna of Mountain Regions.

In mountain regions there is generally sufficient moisture for the growth of forests, but, with the decrease of temperature in proportion to increase of altitude, the forests are confined to a zone, higher or lower according to latitude. In the Colombian Andes the limit of trees is 3,300 metres above sea level, in the Swiss Alps, on an average i,800 metres. The forest fauna extends to this limit ; above, and adjoin ing it from the lower limit of the region of snow, a characteristic alpine fauna is found. As the height above sea-level increases, atmospheric pressure and temperature decrease. The low atmos pheric pressure, i.e., the small quantity of oxygen in the air, causes an increase in the number of red blood corpuscles in homoiother mal animals. Plain-dwelling mammals suffer from lack of oxygen if they ascend high ("mountain sickness") . Nevertheless, mammals are able to dwell at heights of more than 6,000 metres ; e.g., the rodent Ochotona wollastoni at 6,125 metres on Mt. Everest. More important is the decrease in temperature, and the shortening of the warmer season in alpine regions. For these reasons the num ber of species decreases rapidly with increasing altitude. In Switz erland up to 700 metres there are 178 species of birds, up to 1,800 metres 178 species (partly other kinds), in the Alpine region (up to 2,700 metres) 90 species, in the region of the snows only 8 species. The species of gastropods, insects and mammals show a similar decrease. The special conditions of temperature at ground level lessen, for small animals, the unfavourable climate of moun tain regions. In consequence of the strength of the sun's rays, the surface layers of the ground, and the air in the tussock-growth of plants which covers them, is rapidly heated; on summer days with an air temperature of 23° C, the temperature at the surface of the ground may rise to 40-50°. Insects, mites, gastropods, salaman ders and lizards are able, therefore, to move about in search of food ; at night they find shelter from the cold in the surface layers of the earth and under stones. Flying insects are compara tively scarce; at sunset, all of them settle on the ground. The steepness of the mountain slopes facilitates the removal of loose earth by rain and torrents. In many places the rock is exposed and harbours a peculiar fauna; birds, such as the Alpine creeper (Ticliodroma), those which nest in cliffs, such as the Alpine chough (Pyrrhocorax-graculus) and the Alpine swift (Apus melba), and ruminants such as the chamois, ibex, musk-deer and yak, which have broadly expanded hooves, enabling them to get foothold. Among insects, those with complete metamorphosis pre ponderate; in particular, beetles, Lepidoptera, Diptera; Orthop tera and Hemiptera, which require more warmth, are poorly repre sented. On the other hand, springtails are numerous. Among Hy menoptera the most numerous are humble-bees, with a hairy cov ering to the body, which retains the heat generated by their move ments. The shorter time amphibians require for development, the higher they ascend the mountain slopes, for the higher a pool, the shorter the time it remains free of ice. In Rana fusca, Hyla, Bu f o, Alytes, Bornbinator, the tadpole stage lasts from 85 days increas ing to 134 days; their upper limit is from 2,600 metres decreasing to 1,500 metres. The upper limit of reptiles is connected with their manner of reproduction, viviparous species ascending highest. In the Alps, the common lizard Lacerta vivipara ascends to more than 3,00o metres, the common viper (Vipera beaus) to 2,75o me tres, the slowworm (Auguis fragilis) to 2,000 metres. Oviparous reptiles inhabit the lower slopes. Viviparous forms and therefore their embryos, are constantly exposed to the sun, while deposited eggs are usually in the shade, and are only warmed by the sun from time to time. Homoiothermal animals are more independent of temperature, but are very dependent on food; to obtain it, they often migrate down towards the valleys in winter. Most alpine birds are non-migratory; migratory species are relatively scarce. Homoiothermal animals in high mountains are often larger than their relatives in the plains; e.g., the tree-creeper (Certhia familiaris) and the hedge-shrew (Mus sylvaticus) of the Swiss Alps. Many specifically mountain dwellers cannot live in the plains ; they are isolated in the mountain ranges by the sur rounding lowland, and have been transformed into geographical races; e.g., the ibex (Capra ibex) of the Alps, Caucasus, Taurus mountains, Mt. Sinai and Abyssinia.

Fauna of Polar Regions.

Varieties similar to those in the fauna of the lower slopes of mountains are present in regions approaching the North Pole. Organisms in the Arctic and in the Antarctic regions are very different, owing to the difference in the climate. In Arctic regions there is a short summer, with sunshine and higher temperatures, which awakens plant and animal life; in the Antarctic, although the winter is not quite so cold, the summer is cooler, and the sky is constantly overcast, and therefore little life develops on land. Arctic and the highest alpine regions have many species in common, which are absent in the intervening areas; such are the Alpine hare (Lepus timidus), the ptarmigan (Lagopus mutus), the gastropod Acanthinula harpa, and some lepidopterans, which traversed the warmer intervening areas dur ing the Glacial Period. The number of arctic insects is not great; Diptera and Lepidoptera are most abundant, Orthoptera and Hemiptera are rare. Among Hymenoptera, bumble-bees are rela tively numerous, and are strikingly large, thus having proportion ately smaller surface to give off heat. The few species of gastro pods are small. Amphibians and reptiles are found only in the southern portion and these species are the same as those ascend ing highest in mountain regions. Homoiothermal animals are char acterized by adaptations for conservation of heat ; they are sturdy, have short appendages (ears and tail) and a thick covering of f ur or feathers. The white colour of so many polar birds and mam mals is important in reducing heat radiation. Experiments have shown that the proportion of heat given off by light-coloured and black guinea-pigs is as 100 :124. Polar mammals do not hibernate, as the frozen ground provides no protection from temperatures below freezing point. The number of birds and mammals is small, apart from those which find their food in the sea. In eastern Greenland, besides polar bears and seals, only seven kinds of mammals are found (the hare, lemming, musk-ox, reindeer, er mine, arctic fox and wolf). In Spitsbergen, there are only two kinds, the reindeer and arctic fox. In the Antarctic terrestrial birds and mammals are absent ; all homoiothermal animals are confined to the sea.

Animals of Islands.

The characteristic peculiarities many island faunas have in common are due chiefly to isolation. Ani mals of islands are originally derived from those of continents, and the sea forms a barrier preventing the influx of the parent species. This barrier, however, is not insuperable. In many cases land connections were formerly present. Such islands are termed "continental," in contrast to "oceanic" islands, which have arisen in the sea by volcanic agency, or as coral reefs, and were originally devoid of terrestrial animals. Isolation brings about differentiation of species, each form developing its peculiarities undisturbed by intercrossing with the original stock. This process being con tinued, races are produced confined to certain localities. In all islands the length of the time of separation, and the degree of iso lation, i.e., the distance from the mainland, is important; the longer and more complete the isolation, the greater the degree of differentiation of the species. Madagascar has long been isolated; forms of Ethiopian origin are here so greatly differentiated that, for example, all non-volant mammals except a few later immi grants belong to endemic genera, and, usually, also to sub-families and families not found elsewhere. On the other hand, the British Isles, which have been separated only since the end of the Glacial Period, have only one peculiar vertebrate (the red grouse).In ancient oceanic islands, the number of endemic species in creases with the distance from the mainland. While the Azores, in addition to endemic species, have many in common with Europe and Africa, most of the fauna of St. Helena is endemic, and in that of the Hawaiian islands (more than 3,000km. from the mainland) there are numerous genera, and among gastropods and birds, families also, which are not found elsewhere.

The isolation of oceanic islands by the sea implies selection in the fauna. Mammals, amphibians and freshwater fishes are unable to overcome this obstacle, and are therefore absent. Reptiles can seldom reach such islands, but birds can do so much more fre quently. Flying insects may be carried to them by winds, and some even reach them unassisted. Terrestrial gastropods and wood-boring insects (e.g., weevils) reach them on driftwood.

Isolated regions offer shelter from rivals and enemies. Thus, in Tasmania, the carnivorous marsupials Tjiylacinus and Sarco philus can hold their own, but on the Australian continent they succumb to the imported dingo. Loss of the power of flight, which often occurs in birds inhabiting islands, is connected with the ab sence of mammals; in the Galapagos Islands there is a flightless cormorant (Nannopterus), in New Zealand the kiwi (Apteryx). On other islands, flightless birds have become extinct in historical times, as in Mauritius. The large size of the birds found on islands may be connected with the loss of flying powers; the limit of size imposed by flight disappeared when this was abandoned. On the other hand, we frequently find dwarf varieties of mammals on islands; on the islands of the Red sea Gazella arabica does not exceed a third the normal weight of the species.

Some of the peculiarities of animals of islands are explained by the climate. On small islands feeble fliers are in danger of being carried out to sea by strong winds. For this reason most insects on the Polynesian islands take shelter from wind; in the East Frisian island few flying insects are found. Animals which feed on these insects (flycatchers, swallows, small bats, etc.) are also ab sent. On the storm-swept islands of the Subantarctic, numerous insects have vestigial wings (of eight species of flies in Kerguelen one only has normal wings).