Wars of Diadochi

DIADOCHI, WARS OF (323-281 B.c.). The wars of the Diadochi, or Successors, though outwardly civil wars ending in the disruption of the Alexandrine empire, were inwardly the birth pangs of a new civilization begotten by Persian gold set into cir culation through strife. Few periods in history have produced so many great generals, the reason being that the chief participators in these wars, namely, Antipater, Craterus, Perdiccas, Ptolemy, Lysimachus, Seleucus and Eumenes had all been selected by Alexander and trained in his campaigns.

To the Death of Perdiccas, 321 B.C.

Alexander died in June 323, but before the year was out civil war was raging throughout Greece. This conflagration was known as the Lamian war, and to quell it Antipater sent for Craterus then in Cilicia on his way back to Greece with Alexander's discharged veterans. On his arrival he met the Grecian allied forces on the plains of Crannon and routed them. Free of this menace, Antipater and Craterus, fearing the growing power of Perdiccas, entered into a league with Ptolemy, who was nervous lest Perdiccas should attempt to dispossess him of Egypt. Nor were his fears unfounded, for in the spring of 321 Perdiccas, accompanied by Philip Arrhidaeus, the weak-minded half-brother of Alexander, marched against Egypt, whereupon Craterus and Neoptolemus invaded Asia, both being killed in a battle with Eumenes. Perdiccas did not, however, live to hear of this victory, for on the Pelusiac branch of the Nile his men mutinied and assassinated him. The battle fought by Eumenes is mainly of strategical interest, since Perdiccas and Eumenes held a central position and were threatened by Antipater from the west and by Ptolemy from the south. Antipater's plan was first to smash Eumenes and hold off Perdiccas, secondly to concentrate against the latter. Perdiccas attempted to counter this plan by sending Eumenes to hold back Antipater's two generals whilst he fell upon Ptolemy. Both coalitions aimed at destroying each other in detail, the one working on interior lines and the other on exterior. From the very outset of this war we find strategy domi nating tactics, the reason being that all the generals concerned are men of high military ability.

To the Death of Eumenes, 316 B.C.

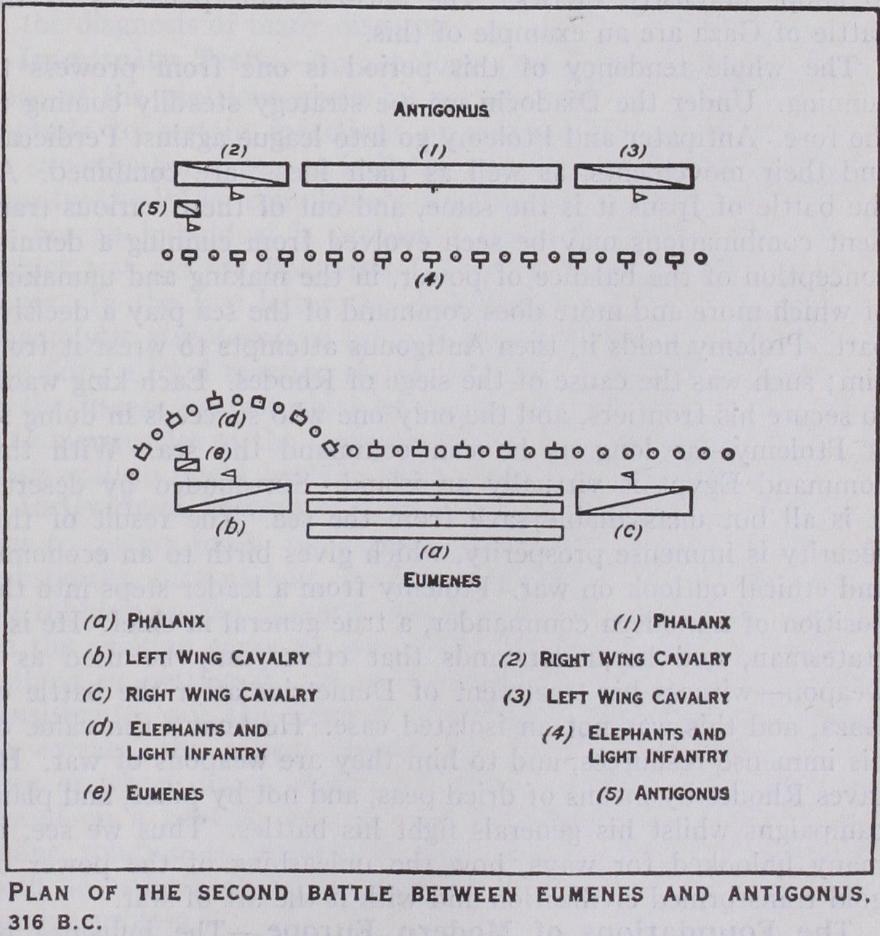

By the death of Per diccas the preponderance of power was thrown into the hands of Antipater, Ptolemy and Antigonus. As Antipater had just suffered a reverse, Antigonus, seeing Eumenes without an ally, marched against him. Eumenes, robbed of the fruits of his victory, was faced by a mutinous army. Putting to death the ringleaders he turned to meet Antigonus, whereupon his cavalry under Apollon ides deserted to the enemy. This compelled Eumenes to seek refuge in the fortress of Nora, which was at once besieged by Antigonus. Meanwhile Antipater died, but shortly before his death he set aside his son Cassander and appointed as his successor Polysperchon. Antigonus, hearing of the differences between these two, saw a chance of increasing his dominion, and to be quit of the siege he proposed favourable terms to Eumenes, who was at once bought over by Polysperchon, who sent to him the Argyras pides (Silver Shields), a formidable body of Alexander's veterans. A series of manoeuvres now took place, the two antagonists com ing into contact in Media. Eumenes had 35,000 foot, 6,1oo horse, and 114 elephants ; and Antigonus 82,000 foot, 8,5oo horse and 65 elephants. The orders of battle of the two armies are given in the diagram.The tactics of this battle are interesting. Antigonus, seeing that Eumenes had deployed his best horsemen on his right, drew up I,000 horse archers and i,000 lancers in columns of squadrons so that they could "charge in manner of a running fight, wheeling off one after another, and so still renew the fight by fresh men." He did this to hold his enemy's main attack. Eumenes, to protect his left wing, drew up his elephants in a demi-lune, from which it may be inferred that this wing was to be refused. Antigonus in order to protect his right wing, which was to deliver the main attack, extended his elephants in a semi-circle on its outer flank.

Antigonus advanced with his right leading, but not being able to encounter the elephants he wheeled outwards and poured showers of arrows on to his enemy's left flank. Eumenes, with drawing a force of cavalry from his right, fell upon the flank and rear of Antigonus's right wing and pursued it into the mountains. The phalanxes now clashed together, the Silver Shields carrying all before them. Antigonus was advised to retire, but he was too good a soldier to take this course. He noticed that the pursuit of Eumenes and the movement of the Silver Shields had created a gap between the phalanx and the left wing cavalry. Through this gap he charged, and struck Eumenes' right flank in rear driving it from the field. The battle was indecisive, and during the night both armies retired. Eumenes was now compelled to disperse his force in order to live. Antigonus, determining to take advantage of this, abandoned the main road for a little-known desert track. Learning of this, Eumenes lit fires "within the compass of 7o fur longs," which so completely deceived Antigonus that he abandoned the track; this allowed Eumenes to concentrate his forces. The armies now met, that of Antigonus numbering 22,000 foot, 9oo horse, and 65 elephants; and that of Eumenes 36,7oo foot, 6,o5o horse, and 114 elephants. (See plan below.) Eumenes, hearing that Antigonus was with his right wing, faced him with his left, in front of which he drew up in a half-moon formation, the bulk of his elephants linking them up with light infantry. In his centre he marshalled his targeteers in front, the Silver Shields behind them, and the "foreigners" in rear. In front of the targeteers he extended a line of elephants and light troops, his right wing being ordered "to retire leisurely as he fought, and diligently to observe the events of the other side." As the elephants advanced on each other a tremendous dust was raised, under cover of which Antigonus sent out a force of cavalry to pass round the enemy's flank and seize his baggage camp. Eumenes charged f or ward through the dust, a large number of his horse deserting him. He was followed by the Silver Shields who once again carried all before them, but on account of the flight of Eumenes' cavalry they were surrounded by the enemy's. Learning that their baggage and wives were in the enemy's hands they were thrown into con sternation. Thereupon Antigonus offered to hand their camp back to them if they would desert and surrender Eumenes. This they agreed to do, and after a week's captivity Eumenes was put to death by his guard.

To the Death of Heracles, 310 B.C.

Whilst Eumenes was warring in Asia, Olympias, the mother of Alexander, put to death Philip Arrhidaeus. Thereupon Cassander, who by bribery had won over many of Polysperchon's soldiers, besieged her in the fortress of Pydna. In the spring of 316, with Roxana and her child (Alex ander's widow and son), she surrendered to him and shortly after was assassinated. The death of Eumenes having freed Antigonus from opposition in Asia, he made the assassination of Olympias an excuse to destroy Cassander. Through self-preservation, Lysi machus, Ptolemy and Seleucus formed an alliance against him, and in 314, to weaken Cassander, Antigonus promised freedom to the Grecian cities. The result of this was that the Aetolians entered into alliance with him, and Cassander was forced to march against them. Meanwhile Seleucus gained over Babylonia and founded the Seleucid dynasty.In 311, Cassander having defeated the Aetolians, a temporary peace was patched up, the terms of which were : That Cassander was to hold Macedonia until Roxana's child should come of age ; Lysimachus to govern Thrace ; Ptolemy to retain Egypt, and Antigonus to rule all the provinces of Asia. No sooner was this peace agreed upon than Cassander assassinated Roxana and her child, whereupon Polysperchon, influenced by Antigonus, espoused the cause of Heracles the pretender, proclaiming him Alexander's son by his mistress Barsine. Cassander, whose position was insecure, offered Polysperchon complete control of the Pelopon nesus if he would put Heracles out of the way, which was promptly done.

To the Death of Antigonus, 300 B.C.

To punish Cassander, in 307 B.C., Antigonus sent his son Demetrius to the Peiraeeus. The Athenians mistaking his fleet for that of Ptolemy allowed him to enter the port, whereupon Athens opened her gates to him. The next three years were spent by Demetrius in a series of campaigns. At the battle of Gaza, 312 B.C., he was defeated by Ptolemy and Seleucus, captured and at once released. Concentrating his main cavalry force in his right wing, Ptolemy protected it against Demetrius's elephants by a palisade pointed with iron spikes, in front of which he placed his light infantry. As the elephants advanced they were plied with darts, and when they struck the iron spikes they were thrown into such confusion that the Deme trians lost heart and withdrew.In 308 B.C. Demetrius, realizing that Ptolemy's strength lay in his command of the sea, defeated him in a.naval battle off Cyprus, and in the following year he set sail for Rhodes, the siege of which was the greatest exploit of his eventful life. At this siege every type of device was made use of by besieged and besieger. Demet rius employed 30,00o artificers and workmen to build his towers and engines; Helepolis, the largest tower he built, required 3,400 men to move it. He constructed a ram 'Soft. long which was moved on wheels by i,000 men. In place of ramming his enemy's war galleys, he cleared their decks by veritable broadsides of missiles, and Plutarch tells us that he built galleys of 13 banks of oars, and some of even 15 and 16 which "were as wonderful for their speed . . . as for their size." Nevertheless, in spite of his inventive genius, in the autumn of 302 B.C. he was compelled to raise the siege, for Ptolemy, still controlling the seas, resup plied the city.

Returning to Athens, in April 3or, as he was marching into Thessaly to meet Cassander, Demetrius was recalled to Asia by Antigonus. The reason for this was that Ptolemy, Seleucus and Lysimachus, fearing that should Cassander be defeated Greece would be added to the kingdom of Antigonus, determined to relieve the pressure by attacking Antigonus in Asia. In the spring of 30o B.C. the opposing forces met at Ipsus, in Phrygia. Deme trius with the main force of cavalry charged Antiochus, the son of Seleucus, routed him, and then pursued him. Seeing what had happened Seleucus blocked his return by a line of elephants, and then in place of charging Antigonus threatened him with attack, so giving time to such of the enemy who wished to desert to come over. This a large body did, and when a strong force of the enemy drew up to charge Antigonus, one of those about him cried out : "Sir, they are coming upon you!" To which the old general replied dryly : "What else should they do?" and was at once smit ten down by a multitude of darts. His kingdom was then broken up, chiefly to the profit of Seleucus.

To the Death of Seleucus, 281 B.C.

In 296 B.C. Cassander died, and Demetrius returning to Greece became master of Mace donia. There he prepared to invade Asia, which threat resulted in an alliance between Seleucus, Ptolemy and Lysimachus. Demetrius, forsaken by his troops, surrendered himself to Seleu cus, who kept him a prisoner until his death in 283 B.C. In 277 B.C. his son Antigonus Gonatas regained the throne of Macedonia, and his descendants, the Antigonid kings, held it until the battle of Pydna, in 168 B.C. In 283 B.C., Ptolemy, king of Egypt, died at the age of 84, and two years later, at the battle of Coron, Lysim achus, at the age of 8o, was killed by Seleucus, who himself was murdered by Keraunos, the eldest son of Ptolemy, in 281 B.C. Thus perished the last of the Diadochi.

The Art of War of the Period.

In spite of their many bril liant episodes, the wars of the Diadochi constituted a period of military decadence. The first cause for this rot was the sudden loss of Alexander's genius ; the second, the imitation by the Suc cessors of his actions without understanding them, and, lastly, the immense influx of Persian gold.

When Alexander died his art died with him; and though several of his generals showed true knowledge of the art of war and on occasion actually improved on his minor tactics, they lacked his vision, and after his death the glamour they had gathered was lost and only a dream was left, which as years passed by grew fainter and more obscure. Eumenes was an able leader, full of resources and craftiness, yet in his first battle with Antigonus he merely copied the Alexandrine tactics in place of breathing out their spirit. He made his right wing the decisive attack, as Alexander had done; but Alexander always struck at his enemy's command, the decisive point, and as Antigonus was commanding his own right wing Eumenes should have attacked him with his left. In his second battle he does not repeat this mistake, which shows how little of essential value is learnt even by intelligent soldiers until disaster hammers knowledge home.

The Persian gold, with which Alexander intended to develop his empire, was spent in war. The mercenary now came into his own, and not only was he bought and sold on the battlefield, which if it did not destroy discipline destroyed all reliance in it, but he changed the art of leadership and of military organization. A mercenary army will serve any master for pay, and when a general is forced to hire mercenaries he looks for the most formidable type of troops. In this day the sarissa armed hoplites were of this category, consequently a man who looked for employment as a mercenary knew that as a hoplite he would command higher pay than as an archer or a peltast. The result was a disruption of Philip of Macedon's organization and a steady return to the Spar tan tactics.

In the army of Alexander leadership was based on heroism, but in the armies of the Diadochi it was based on pay. The result of this was that heroism was replaced by craft. Warfare, in a low and underground way, became more intellectual, and leadership had to follow suit. The leader was no longer a hero but a diplo matist, and as he led by gold in place of by valour, he crept behind his men, or, more frequently still, hired a hero to lead them, and from a safe distance instructed him what to do. Thus the merce nary separated leadership from command, and the whole art of war changed. Another influence of gold was that warfare became mechanized. Gold stimulated invention, and invention stimu lated industry, and industry was applied to war. Projectile weapons came more and more into use, and as they were difficult to move on the battlefield they induced generals more and more to adopt defensive tactics. The anti-elephant palisades at the battle of Gaza are an example of this.

The whole tendency of this period is one from prowess to cunning. Under the Diadochi we see strategy steadily coming to the fore. Antipater and Ptolemy go into league against Perdiccas, and their movements, as well as their ideas, are combined. At the battle of Ipsus it is the same, and out of these various tran sient combinations may be seen evolved from cunning a definite conception of the balance of power, in the making and unmaking of which more and more does command of the sea play a decisive part. Ptolemy holds it, then Antigonus attempts to wrest it from him ; such was the cause of the siege of Rhodes. Each king wants to secure his frontiers, and the only one who succeeds in doing so is Ptolemy—as long as he can command the sea. With this command Egypt is virtually an island. Surrounded by deserts, it is all but unassailable save from the sea. The result of this security is immense prosperity, which gives birth to an economic and ethical outlook on war. Ptolemy from a leader steps into the position of a modern commander, a true general in chief. He is a statesman, and he understands that ethics may be used as a weapon—witness his treatment of Demetrius after the battle of Gaza, and this was not an isolated case. He knows the value of his immense resources, and to him they are weapons of war. He saves Rhodes by means of dried peas, and not by pikes, and plans campaigns whilst his generals fight his battles. Thus we see, in many unlooked for ways, how the unleashing of the power of gold transformed civilization and with it the art of war.